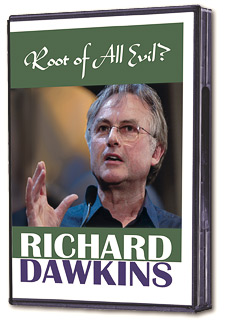

The Root of All Evil?

now available in North America!

(exclusively from the Skeptics Society)

This two-part documentary written and presented by evolutionary biologist Dr. Richard Dawkins, is the controversial DVD that complements his bestselling book The God Delusion. Dawkins presents his view of religion as a cultural virus that, like a computer virus, once downloaded into the software of society corrupts many of the programs it encounters. It isn’t hard to find examples to fit this view; one has only to read the dailies coming out of the Middle East to see its nefarious effects.

Dr. Richard Dawkins is the author of

The Selfish Gene, The Blind Watchmaker, Climbing Mount Improbable, Unweaving the Rainbow, and The Ancestor’s Tale.

Ann Druyan, wife and collaborator of the late Dr. Carl Sagan (photo by Ron Luxemburg ©)

Shermer interviews

Ann Druyan

This week on Skepticality, we’re very pleased to present Dr. Michael Shermer’s new, in-depth interview with author and editor Ann Druyan, wife and collaborator of the late Dr. Carl Sagan. In this insightful hour, Ann gives us a look into Dr. Sagan’s thoughts on science, religion, and her decision to collect his acclaimed Gifford Lectures in the new book The Varieties of Scientific Experience: A Personal View of the Search for God.

Also of interest…

In this week’s eSkeptic, David Ludden reviews Thomas Kida’s book Don’t Believe Everything You Think: The 6 Basic Mistakes We Make in Thinking. David Ludden is an assistant professor of psychology at Lindsey Wilson College in Columbia, Kentucky.

Not Very Comforting

a book review by David Ludden

I generally include a demonstration of visual illusions in my psychology classes. After several examples in which I induce students to see things that are not there, and to not see things that are there, I end with a discussion of how we can never trust that our senses are telling us what is actually out there in the real world.

“Well, that’s not very comforting,” blurted out one of my students not too long ago after one of these demonstrations. And she was right — much of what we have learned in cognitive psychology is discomforting. Six of these uncomfortable facts about human thinking are explored in psychologist Thomas Kida’s new book, Don’t Believe Everything You Think. Throughout the book, Kida shows how these errors permeate our thinking, leading us not only to paranormal and pseudoscientific beliefs but also to more subtle cognitive errors that are dangerous to our health and wealth, both as individuals and as a society.

The first error is that we prefer stories to statistics. Kida illustrates this with an example of car shopping. Although Consumer Reports rates the car you are considering as very reliable, a colleague of yours owns that model and complains that it has been nothing but trouble. Would you still buy the car? In general, people trust unique personal experiences over “impersonal” data, even though the statistics represent the aggregated experiences of many people.

The second error is that we seek to confirm rather than question our beliefs. Furthermore, we are more likely to remember evidence that supports our beliefs rather than evidence that does not. This confirmation bias leads to stereotypes and prejudices as well as to pseudoscientific thinking. For example, if you believe in moon madness, you will notice the occasional crazy driver on a moonlit night without noticing all the other drivers (including yourself) that are driving normally.

The third error involves a general misunderstanding of the role of chance and coincidence in shaping events. Few people understand how to calculate the probabilities of events, and so people generally rely on intuitions developed from personal experience. This leads to cognitive errors such as the gambler’s fallacy, in which people believe, for example, that tails is “due” after a run of heads, and the hot-hand fallacy, in which people believe that a basketball player who makes several shots in a row will likely continue making shots. Neither belief is true, and they are logically contradictory as well, but both beliefs are commonly held.

Trusting the reliability of our senses is the fourth error Kida discusses. “I know what I saw” is a common assertion, but in fact we never know for sure that our senses are accurately reporting what is going on around us. This is because perception is a reconstruction by the brain of the external world based on limited sensory inputs, and as such is subject to error. Not only is our perception influenced by our expectations, hallucinations are far more common than people think and are not just the product of drug abuse or psychosis.

The fifth error is that we have a tendency to oversimplify our thinking. The heuristics we use to guide our thought processes help us prevent information overload and let us make decisions in a timely manner. However, these mental shortcuts can also lead us widely astray and leave us vulnerable to deception by those who wish to manipulate us.

Finally, we need to be aware that our memories are faulty. We all know that we forget things sometimes, but we generally assume that what we do remember is an accurate representation of past events. However, a vast program of memory research has shown that human memory is exceedingly unreliable. The average person views memory as a type of video recording, but in fact it is a reconstruction based on current beliefs and expectations as well as the suggestions of others. Over-reliance on memory recall has serious consequences. For instance, the criminal justice system still places inordinate weight on eyewitness testimony in spite of all the evidence showing how unreliable it is.

These six errors in thinking are part of our evolutionary makeup, and so there is little we can do to change them. However, Kida is not pessimistic. Rather, he maintains that we can overcome these weaknesses with a two-step approach. First, we need to be aware of our cognitive biases so that we can anticipate when we are likely to fall victim to them. Second, we need to take a skeptical approach in all aspects of life. The skeptical approach Kida espouses is none other than the scientific method. Thus, Kida rejects the idea that there are various ways of knowing, depending on the field of inquiry. Although our beliefs may comfort us, Kida maintains that “we must learn to accept how much we don’t know” (p. 237). It is only through the skeptical evaluation of evidence that individuals as well as societies can make informed decisions.

Don’t Believe Everything You Think provides an excellent review of the literature on the psychology of belief, touching on all the standard topics of paranormal and pseudoscientific thinking. However, Kida also discusses important topics not always covered in the skeptical literature. For example, Kida’s examination of the role of the media in perpetuating pseudoscientific thinking among the general public is excellent. Furthermore, Kida’s examples of fallacious thinking in investment and finance are new to the skeptical literature and likely to challenge the assumptions of even the hardest skeptic. Kida’s demonstration of the folly of financial forecasting is thoroughly convincing, and readers of this book will be asking their stock brokers and financial analysts some hard-hitting questions.

Although it is always uncomfortable to be reminded of just how fallible we are, Kida does provide his readers with a modicum of solace by offering copious advice on how to anticipate and work around our innate cognitive biases. Don’t Believe Everything You Think is essential reading for anyone interested in the psychology of belief and pseudoscientific thinking. It also provides one of the best arguments around for the importance science literacy — the scientific method is the antidote to our fallible minds.

Shermer labeled a 9/11 “diversionary agent”

The 9/11 Truth Movement, which suggests “that elements within the US government and covert policy apparatus must have orchestrated or participated in the execution of the attacks for these to have happened in the way that they did,” has branded Skeptics Society Director Michael Shermer an agent of misinformation and distraction — a “diversionary agent”!

Read more about 9/11 in a previous eSkeptic and in an upcoming issue of Skeptic magazine: Volume 12, Number 4 (to be published this month).