Skepticism Loses Two Stars

Last week we lost two good friends: Jerry Andrus and Paul MacCready. In this week’s eSkeptic, instead of repeating formal facts from published obituaries, we provide links to two such obituaries along with Michael Shermer’s personal remembrances of his good friends and a photo collage of each.

A Fond Farewell to

Jerry Andrus & Paul MacCready

by Michael Shermer

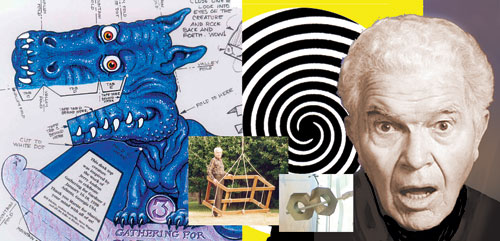

left to right: Jerry Andrus’ dragon illusion; “Impossible Box” and “Nuts”; Jerry Andrus

Jerry Andrus

Jerry Andrus died on Sunday, August 26th from advanced prostate cancer.

I was first introduced to Jerry’s work in the mid-1980s at Caltech for an event on how our senses and brains can be easily fooled. Jerry was a brilliant and talented close-up magician, but he was best known for his 3D illusions that, when presented at a certain angle, distance, and lighting, could completely blow your mind with shape-shifting, figure-flipping regularity. (His website presents excellent video demonstrations of many of these — click on “eye tricks”.) With Jerry’s permission, I incorporated into my public lecture on “The Power of Belief” his famous 3D impossible crate illusion (pictured on his website), explaining that it is one thing to see the various 2D illusions typically presented in introductory psychology textbooks; it is quite another thing to see them re-created in 3D. Jerry Andrus was the world’s greatest 3D illusionist.

Although Jerry had no formal degrees, he was one of the most creative, eclectic, and diverse minds I have ever encountered, a true polymath. (It sometimes makes me wonder if a college education, especially a higher degree, can confine the mind and restrict thinking into pre-arranged categories that attenuates cross- and inter-disciplinary pollination, but I’ll save that discussion for another day.) His thoughts ranged widely across all fields, and he devoted his life to thinking and creating, all toward the goal of trying to better understand how the world works, most notably the world of the mind. I brought Jerry to Caltech on a number of occasions for our annual conferences, where he tirelessly held court in a section of the hall devoted just to his illusions, sitting there for hours on end patiently showing people just how unreliable our senses and brains can be under the influence of his special magic. Even well into his 80s, Jerry managed the trip to L.A. from Oregon with his suitcases full of illusions, and not just for the Skeptics Society conference, but several times a year at the Magic Castle in Hollywood, where he was a resident magician working the close-up magic room.

What he did for science and skepticism (which was considerable) aside, however, what I most remember about Jerry was his kindness, honesty, and genuineness. I think it was James Randi who said that if you looked up the word “integrity” in the dictionary there would be a picture of Jerry Andrus. Jerry was kind and considerate to everyone he met. He could be asked the same question a hundred times in a day about some illusion he was showing, and he would answer it with the same enthusiasm the hundredth time as he did the first time. Even though he practiced deception professionally as a magician, Jerry Andrus could no more deceive someone in regular life than he could fly (and Jerry couldn’t fly, although I suspect he thought about how to create an illusion that he could). Jerry simply wanted to know the truth about the world. He wanted to cut straight through political, religious, and social barriers to our understanding to get to the heart of a problem. This he did as well as and often better than most professional Ph.D. scientists I have met. We shall miss you so very much Jerry. Your legend lives on.

- READ the Albany Democrat Herald article about Jerry’s death

- VISIT “The Friends of Jerry Andrus” website

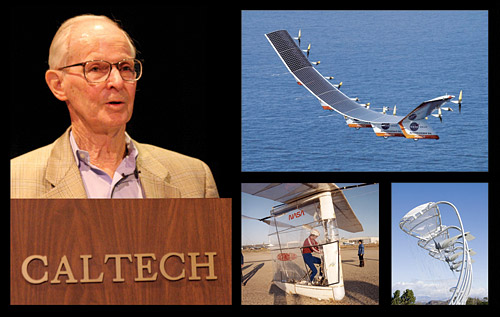

Paul MacCready speaking at Caltech; MacCready inventions including: a solar-powered airplane; the cab of a human-powered airplane: and a wind turbine

Paul MacCready

Paul MacCready died on Tuesday, August 28th from brain cancer.

I first came upon the name of Paul MacCready in 1980 when I was at a bicycle convention in Cleveland, Ohio. It was a heady time in the sport. The speed skater Eric Heiden had just won five gold medals in the winter Olympics but proclaimed that his true love was cycling and he was turning professional in the sport. The film Breaking Away was a surprise hit at the box office, introducing the American public to the intricacies of bicycle racing, such as drafting behind trucks, shaving your legs, and breaking away from the peloton of other cyclists (and, in the film’s coming of age message, breaking away from home). And a young man named Bryan Allen had just ridden a human-powered airplane across the English Channel. That plane was designed and built by Paul MacCready.

In subsequent years I would occasionally run into Paul at IHPVA events (International Human-Powered Vehicle Association), where I was racing them and he was designing them. Paul told me that he solved the problem of human-powered flight by watching birds, explaining that nature had millions of years of trial-and-error evolutionary tinkering so why not learn from her experiences? (As Leslie Orgle said: “Evolution is smarter than you.”) The solution was light weight materials and huge wings, which Paul and his team managed to build on the slimmest of budgets. (Paul’s other now-oft-told story was his motivation — he was in considerable debt and needed the prize money offered for the first person to fly a human-powered plane, one prize for flying through a figure-8 course and a second prize for flying across the English Channel, totaling about $300,000.) Paul managed to triple the size of the wings other teams were building, without increasing the weight of the overall plane. Then he had to find a light weight but powerful motor. Enter Bryan Allen, a skinny racing cyclist who managed to keep the jury-rigged contraptions aloft long enough to nab the prizes (the Gossamer Condor for the figure-8 course, the Gossamer Albatross for the English Channel, the former of which hangs in the Smithsonian’s Air and Space museum next to Lindbergh’s Spirit of St. Louis plane). With the prize monies, Paul was able to launch his company AeroVironment, now one of the world’s leading creators of innovative technologies. What a perfect blend of science, technology, and athletics!

One Sunday morning in 1986 Paul called me at home to invite me to a lecture at Caltech that afternoon, sponsored by the Southern California Skeptics, which I had never heard of. He explained that it was a group of people interested in science, reason, and critical thinking about controversial claims, and that it involved such people as James Randi, Murray Gell-Mann, and Richard Feynman, whom I had most definitely heard of. So I went and the rest is skeptical history; 20 years later I’m still deeply ensconced in the skeptical movement. Over the years Paul and I would run into each other at various functions and conferences where we were both speaking or just hanging out. Paul’s message was as simple as it was profound: doing more with less. Environmentally conscious, technologically clever, and culturally grand, Paul wanted to change the world through reason, intelligence, and creativity. He wanted to get us off fossil fuels without having to give up our beloved toys. From human-powered planes he moved onto developing solar-powered planes (e.g., the Gossamer Penguin and Helios), solar-powered cars (e.g., the GM Sunraycer), and electric cars, all of which brought him international acclaim — Paul was voted by his colleagues as the engineer of the 20th century — the entire century!

Paul took his message to the public. Eschewing large speaking fees that he could easily have demanded, Paul would speak to anyone anywhere if he thought that he had a chance to influence people, including and especially children. Paul once came to my young daughter’s 2nd grade class with numerous props to demonstrate how much fun science can be, and especially how much we can learn about nature just by asking the right questions. Even though he was from a well-to-do family, earned a Ph.D. from Caltech, and traveled among the most influential circles in society, Paul was completely unpretentious, conversing in the same manner whether he was talking to a room full of undergraduate students or Nobel laureates and Pulitzer Prize winners. I know because we’ve had them both in the same room at Caltech with Paul explaining to them all about what they can do to change the world. Through his words and especially his deeds, Paul MacCready changed the world, and though we will miss him dearly his influence will live on in our hearts and in our actions.

“Haiti UFO” Video Mystery Solved

Since early August, several million people have viewed a YouTube video purporting to show alien spacecraft buzzing a beach in Haiti. The clip — featuring an impressive close-up of one UFO passing directly over the apparently handheld camera — struck many as too good to be true.

As usual, this proved to be the case.

It was the palm trees that gave the game away: the video contains identical trees, revealing it as a computer generated, synthetic scene. I knew that realistic trees swaying in a digital breeze are a hallmark effect of relatively inexpensive computer animation software called Vue d’Esprit, and suspected that the hoax was a viral advertisement for Vue’s newest release.

In an admirable example of a mainstream news outlet digging seriously into a paranormal claim, the L.A. Times quickly got to the bottom of the hoax. They located the computer graphics artist who created the film. He confirmed that it was made in a few hours using Vue d’Esprit and other 3D animation software.

It was not, however, a viral ad. When asked, the president of the company that makes Vue denied they were behind the hoax. Instead, a Hollywood movie producer confirmed that this was a test created for an upcoming film. The artist posted the clip online as a whimsical “sociological experiment.”

The animator also provided the L.A. Times with a new video, entitled “Proof,” featuring the same digital model of a UFO — now amusingly shrunk to the size of a toy hovering outside a café.

Mystery solved. But the implications are chilling: we’re now definitely at the point where seamlessly photorealistic fake UFO footage can be made on an ordinary home computer, quickly and easily, using only a few hundred bucks worth of software.

Graphology, Part 2

Graphology, or handwriting analysis, claims that personality characteristics such as introversion and extraversion can be inferred from the form and structure of letters, words, and sentences (introverts, for example, are said to write in smaller letters, extraverts in larger letters). Shermer puts graphology to the experimental test. WATCH the video >