Give a Gift Subscription

to Skeptic magazine

Skeptics love Skeptic magazine. They especially love to receive a subscription as a gift from a friend! Simply order a subscription to Skeptic magazine and include your friend’s address in the “SHIP TO” form during checkout. Tell us “This is a gift” in the “comments” box and we’ll take care of the rest.

(Order must be placed by 5 pm Pacific Standard Time on December 17th with Priority Shipping selected to ensure delivery by Christmas. US destinations only.)

eSpecial on Dinesh D’Souza book

What’s So Great About Christianity?

This past Sunday Michael Shermer and Dinesh D’Souza squared off in the last of their three great debates on religion and morality. We will be posting the entire debate on our website next week so that you can watch it and judge for yourself who won. You can watch their first debate, at Oregon State University now, and in an upcoming eSkeptic, we’ll link to last week’s debate at George Washington University. In the meantime, if you would like to pick up a copy of Dinesh D’Souza’s book we have a limited number available at a special discounted price of $20 (reg. $28), which you can order now while supplies last. Whether you are a religious believer or skeptic, this is a good read and will give you a pulse on what believers are thinking and arguing of late. ORDER the book >

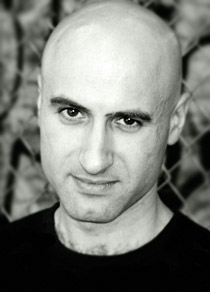

Michael Adelson

Music of the Divine?

This week Skepticality features Michael Adelson, a Staff Conductor for the New York Philharmonic, and Conductor of the Auros Group for New Music in Boston.

Mr. Adelson had the good fortune to study with the late Rabbi Sherwin Wine. A controversial secular organizer, Rabbi Wine founded Humanistic Judaism, a secular movement which provides atheistic and agnostic Jews around the world with a means for organization, mobilization, and a sense of community.

Speaking to Derek & Swoopy as a skeptic, Mr. Adelson shares insights from his lecture series, the “Forum for New Thinking” (inspired by Rabbi Wine). He also takes a critical look at music history, dispelling some false beliefs about artists — creative humans who are often painted with the brush of divine inspiration.

Building on the musical theme, Swoopy talks to Canadian blue grass trio The Dirty Dishes about their new rendition of “Lily The Pink”, an ode to the late 1800’s “queen” of patent medicine Lydia Pinkham.

In this week’s eSkeptic feature, we’re pleased to present a new article by Daniel Loxton, commenting on the history (and future) of patent medicine in light of 2007’s status as the 100th anniversary of active Federal regulation of food and drugs. To mark the anniversary, and as a holiday treat, we also give away a brand new song recording in MP3 format, completely free — ”Lily the Pink,” a century-old folk parody of the claims of the “Queen of Patent Medicine,” Lydia Pinkham.

The Immortal Lily The Pink

The 100th anniversary of the FDA marks a milestone in medicine before which cranks and charlatans ran amok

by Daniel Loxton

Lydia Pinkham, as she appeared on an original antique advertising card, circa 1880.

This year has represented a little-remarked-upon major milestone in American medicine: the 100th anniversary of active Federal regulation of food and drugs. The Pure Food and Drug Act came into effect on January 1st, 1907 — the first step toward the creation of the modern Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and a step forward from the dangerous anarchy of the patent medicine era.

For the first time, drug manufacturers were required by law to disclose the dosage and purity of their products (including, for the first time, disclosing whether they contained poison, alcohol, or narcotics such as heroin or cocaine). They were also required to refrain from deliberately lying about their products, and from fraudulently substituting a claimed ingredient for some other ingredient.

Bizarrely, such laws were needed.

To celebrate this anniversary, and in time for the holidays, we’re pleased to share a brand new, free MP3 recording of a song with roots extending back to the bad old days of unrestrained snake oil: “Lily the Pink” (performed here by the Canadian bluegrass trio Dirty Dishes).

“Lily the Pink” (which evolved from “The Ballad of Lydia Pinkham”) is a comic send-up of the woman called “the queen of patent medicine.” Starting in 1875, Lydia Pinkham built a business empire on the hype-driven sales of a herbal concoction marketed to women for relief of “all those Painful Complaints and Weaknesses so common to our best female population.” In specific, it was intended to address menstrual cramps, and was also “particularly adapted to the Change of Life.”

True to the dizzy style of the unregulated patent medicine era, Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound was promoted with a blizzard of unlikely claims. (As the lyrics of “Lily the Pink” mockingly put it, “She invented a medicinal compound, efficacious in every case.”) Ad copy insisted that it cured everything from headaches to indigestion to farting, not to mention sleeplessness and depression. (Its primary ingredient was booze, so there was no doubt some evidence to support these latter claims.)

Less believably, Pinkham’s Compound was advertised to “dissolve and expel tumors from the uterus at an early stage of development. The tendency to cancerous humors there is checked very speedily by its use.” It was also, the ads said, remarkably effective: “98 out of every 100 women who take the medicine for the ailments for which it is recommended are benefited by it. This is a most remarkable record of efficiency. We doubt if any other medicine in the world equals it.”

Remarkable indeed.

It’s clear that most of these boasts were made up whole cloth, but was any of it true? I asked quack medicine expert Dr. Harriet Hall, “Was Pinkham’s herbal cocktail at all useful for treating anything?”

“The bottom line,” Hall told me, “is that we have no idea whether her product was effective or safe, since it has never been properly tested. We have no good evidence that any of the individual components are safe or effective, and we have no way of knowing what might happen when you mix them. Mixing remedies could do almost anything — they could cancel each other out, have additive effects, vastly increase the chance of side effects, who knows?”

Certainly the Lydia Pinkham Medicine Company had no idea whether its product was safe or effective. It was literally something Pinkham brewed up in her basement, without scientific testing of any kind.

On the other hand, we do now have firm evidence regarding the efficacy of black cohosh, the herb modern alternative medicine proponents most often cite as the effective active component to Pinkham’s Compound. Long considered promising as a treatment for the symptoms of menopause, black cohosh unfortunately bombed in a recent large trial designed by the National Institutes of Health to clarify the ambiguous existing literature and settle the question. The results of this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial were unequivocal: black cohosh is useless for the control of menopausal hot flashes and night sweats.

As far as science can tell, Lydia’s Compound was worthless in public health terms. By free market standards, however, it was a soaring success story. Pinkham’s booming 19th century enterprise raked in hundreds of thousands of dollars a year.

The secret, then as now, was marketing. Pinkham spread the message through national print ad campaigns, door-to-door sales, point of purchase postcard giveaways, and many books and pamphlets that alternated recipes or household tips with ads for her product. The company’s aggressive marketing pioneered a formula for selling quack medicine that is still common today:

- Market directly to women: At the mercy of a male-dominated medical establishment, women were eager to seize control of their own health. Offering them a way to sidestep the then-primitive medical mainstream through the consumption and word-of-mouth promotion of a herbal “alternative” was (and still is) an effective hook for a sales pitch. With its “just us girls” attitude and its “Only a woman can understand a woman’s ills” tagline, the Lydia Pinkham Medicine Company turned shameful social inequality into a source of profit.

- Sow fear of mainstream medicine: “ANY HOSPITAL EXPERIENCE is painful as well as costly and frequently dangerous,” warned Food and Health, a promotional book produced by Pinkham’s company. “Many women have avoided this experience by taking Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound in time…”

- Present your big business as warm, folksy and personal: With Lydia Pinkham’s matronly portrait as its logo, the company was able to present itself as a homemade cottage enterprise. (Fans of the animated TV series Futurama may recognize “MomCorp” and its subsidiary “Mom’s Friendly Robot Company” as comic descendants of the Pinkham advertising model.) Customers who wrote for advice even received personal responses from Lydia herself — for years after she died. In fact, a large, dedicated department within the company churned out replies by the thousands.

Today, this time-tested advertising model — present your mainstream competitors as cold and mercenary, while presenting your own for-profit company’s herbal products as warm, homemade, and natural — is still in wide use in the alternative medicine industry. Indeed, it’s shocking how little has changed.

Today, herbal concoctions and other supplements are cooked up and marketed with wild abandon, with all the unrestrained, unverified boasting of the patent medicine era still on display. We are told (coyly, skirting the few rules for labeling) that herbs and proprietary blends can cure more-or-less anything — just as we were assured by Lydia Pinkham.

Have we really made so little progress against health fraud?

In fact, we’ve come a long way. Today, most medicines are carefully regulated, and consumers can be reasonably assured of the basics: that effectiveness, side effects and interactions are known to some degree; that the bottle contains what the label says; that we are not unknowingly buying bottles of heroin, and so on. We all know that regulation comes with its own cost (drugs take a long time to get to market, for example) but we’re much, much better off than drug consumers in Pinkham’s day.

Unfortunately, current regulations have a hole in them, a hole large enough to drive a truck through — or rather, truckload after truckload of untested, unregulated herbal “supplements.”

The fault for this lies with a piece of legislation called the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994 (DSHEA), which seized back control of patent medicines from the FDA. Driven by strenuous lobbying from supplement manufacturers, this legislation removed all herbs, vitamins, and minerals from FDA oversight — despite the fact that herbs are drugs, exhibiting a full range of effectiveness (or ineffectiveness), dangerous side effects, and interactions with other drugs. Not only are the producers of herbal drugs and other supplements no longer required to prove that their products work — or whether they are safe — but the burden of proof regarding safety is explicitly shifted to the FDA.

That is, anyone can sell any old combination of herbs at any dosage, without any obligation to even try to find out if that product is safe or not.

Only if a supplement kills enough people to get the FDA’s attention, and if the staff of the FDA can find the time and budget, can the FDA then attempt to prove in court that the supplement is unsafe. This costly and lengthy close-the-barn-door-after-the-horses-have-escaped procedure is of course attempted only rarely, and in the most severe cases. The first such case was the banning of ephedra, a supplement suspected in hundreds of deaths. This ban was soon challenged in court (by a company which sells ephedra), and overturned — on the basis that the DSHEA forbids FDA action even in such an extreme case. Luckily, the ruling against the ephedra ban was itself overturned on appeal. After more than two years of legal battles, ephedra supplements are today illegal.

Despite this eventual victory on this one substance, the DSHEA renders the FDA almost powerless over herbal drugs, even if they are known to be dangerous. (Certainly the FDA has no power at all over herbal drugs whose dangers are simply unknown.) This industry-driven legislation inexplicably shifts the cost of safety testing from the companies that profit from the sales of supplements to the taxpayer. More to the point, the risk is shifted from the R&D budgets of companies to the personal health of individual consumers — exactly where we began, in Lydia Pinkham’s day.

Thanks to the DSHEA, the supplement industry has exploded (by several hundred percent or more). It now rakes in tens of billions of dollars a year. Requiring no expensive safety testing or FDA approval, these products are produced with an enviable profit margin, which has of course drawn large pharmaceutical corporations enthusiastically into the supplement industry. (People buying “alternative” herbal products rarely appreciate the likelihood that they are feeding their dollars into the exact same Big Pharma system they are attempting to circumvent, with the only difference being that corporation has been excused from the responsibility or cost of ensuring the safety or effectiveness of one of its lines of drugs.)

We’ve come a long way — but we’ve also, in some ways, come full circle.

This is a shame, because the room for mischief we’ve granted to modern alternative medicine manufacturers is the exact same ground we won at such great cost and effort from the early 20th century patent medicine industry. Like today’s Natural Cures infomercial star (and convicted con-man) Kevin Trudeau, the Pinkham company engaged in a series of running battles with Federal regulators regarding the dishonesty of its labeling and advertising. As is still the case, vagueness and coy insinuation became the best friends of quack medicine manufacturers. (Noting yet another label change in 1939, Time magazine quoted the American Medical Association’s exasperated patent medicine czar: “Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound is ‘Recommended as a Vegetable Tonic in Conditions for which this Preparation is Adapted.’ This statement is about as informative as it would be to say that ‘For Those Who Like This Sort of Thing, This is the Sort of Thing That Those People Like.’”)

It’s clear that we still have much work to do in this important public health arena:

In 1875, one business empire was founded on the sale of Lydia Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound, an untested medical potion for “those painful Complaints and Weaknesses so common to our best female population.”

Today, after a century of wrestling with the patent medicine industry, another company markets an alternative medicine concoction promoted as “beneficial in menstrual and menopausal distress.”

It is called Lydia Pinkham Herbal Compound.

Free MP3: Lily the Pink

left to right: Lisa Olafson, Alison Porter, and Suzie McKenney (photo by Jo-Anne McArthur)

We’re thrilled to present this brand new version of the traditional folk song “Lily the Pink,” a satirical send up of early patent medicine mogul Lydia Pinkham. An original recording made especially for eSkeptic, this song is arranged and performed by country bluegrass trio Dirty Dishes (featuring Lisa Olafson, Suzie McKenney, and fiddler Alison Porter). Many thanks to Alison for organizing this fun project!

Shermer Debunks James van Praagh & Psychics

Michael Shermer explains how psychic James Van Praagh appears to talk to the dead by using such mentalism tricks as cold reading and hot reading.