In this week’s eSkeptic:

Limited Edition

ONLY 10 COPIES LEFT!

Michael Shermer’s First 100 Columns in Scientific American

DONATE a minimum $500 to the Skeptics Society and receive this premium edition, bound and autographed copy of Michael Shermer’s first 100 monthly columns from Scientific American. Only 100 copies were printed. There won’t be another volume like this until Shermer completes his next 100 monthly columns (about 7 years from now)! Donate to the Skeptics Society

About this week’s feature article

The recent election of Jerry Brown as the Governor of California reminded us that back in 1996 Skeptic magazine (vol. 4, no. 3) Senior Editor Frank Miele conducted an in-depth interview with Brown, who was in between political positions and thus willing to speak quite frankly and openly about “money, politics, and who really runs America” (as the subtitle of the article states). Given the fact that Jerry Brown was Governor of California for two terms, ran for Senate in 1982 (where he lost to California Governor Pete Wilson), and ran for President twice (even giving Bill Clinton a run for his money), there are few people more qualified by experience to speak skeptically about American politics. With the mid-term elections still fresh on our minds, enjoy this candid and skeptical look into the inner workings of a modern democracy.

We the People?

Jerry Brown on Money, Politics,

and Who Really Runs America

an interview by Frank Miele

Edmund G. “Jerry” Brown, Jr. has spent much of his life about as deeply “Inside Politics” and as much a part of modern American history as you can. His father, Edmund G. “Pat” Brown, Sr. was a popular Democratic Governor of California. Pat Brown won reelection against (then) former Vice President Richard Nixon, causing the latter to issue his never-to-be forgotten, but not honored, line, “You won’t have Dick Nixon to kick around anymore.” He lost his bid for a third term to Republican Ronald Reagan. Jerry Brown himself served two terms as governor of the nation’s most populous state. He lost a 1982 bid for the U.S. Senate seat to (current) California Governor Pete Wilson. In 1994 Jerry’s sister, Kathleen, then California’s Treasurer, unsuccessfully challenged Pete Wilson for re-election to the governor’s office.

Jerry Brown ran against Jimmy Carter for the Democratic nomination for President of the United States in 1976 (winning Maryland, Rhode Island, Nevada, and California) and ever so briefly in 1980. In 1992 he ran a guerrilla campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination, introducing the now trademarked 800-number. With his knowledge of the inside game of politics, Brown was able to stay in the race until the bitter end (capturing Maine, Vermont, Colorado and Nevada), eventually losing to Bill Clinton. Brown also served as the chairman of the Democratic Party in California 1989–91.

Jerry Brown has never fit into the conventional politician’s mold. He studied for 3 1/2 years for the priesthood and also went to India to work with Mother Teresa. To his critics and opponents, he was “Governor Moonbeam” because of his support for the California Space Satellite program and his encouragement of alternative energy sources. But his refusal to conform has also been his strength and his appeal to millions of voters across the nation. He not only knows the inside game, he also calls ’em as he sees ’em.

Brown now heads WE THE PEOPLE, a non-profit, public interest group located in an industrial section of Oakland, CA, in post-industrial cyberspace at www.wtp.org and toll free at 1-800-426-1112. His WE THE PEOPLE call-in radio program is carried on listener-sponsored Pacifica radio stations across the U.S. WE THE PEOPLE has organized a school for sustainability, a public interest law project, and a continuing series of community forums. Brown has also brought together political activists to discuss, imagine and plan ways to increase citizen activism.

So, for a skeptical look at the democratic process in contemporary America, here is Jerry Brown — a politician out of denial and into recovery — on money, politics, and who really runs America.

Skeptic: I got my introduction to politics when I was a high school student passing out flyers. At the time, I thought what I was doing really mattered. Then local boss told me, “Kid, elections are won by money and votes, in that order!” Was he right?

Brown: Sure he was right. Money pays for the tasks in politics. These include everything from producing and showing TV commercials to hiring individuals to work in the community as pseudo-grass-roots leaders, organizers, and neighborhood activists. Without the money, the modern American political machine grinds to a halt. We don’t have active participation, we have spectatorship. Turnout is down to just above 50% for the presidential election, more like 33% for an off-year congressional election, and even lower in many local elections. So what we have is a theory of democracy, a mythology of citizen power, of “We the People.” But the reality is the manipulation of the people through sophisticated computer-generated letters, TV ads, or what is called astro-turf organizing efforts. Astro-turf is a metaphor for organized person-to-person activity that many campaigns engage in, either by phone or less frequently door-to-door. But all of it is paid for and organized professionally. This is in complete distinction to a system of real volunteers flocking behind the banner and platform of a candidate and then going out to help get him or her elected.

Skeptic: Was that grass-roots, rather than astro-turf, style of politics ever the case in America history?

Brown: American history certainly started out with the political process being a monopoly of white male property owners. It then broadened under the Jacksonian reforms to include more people. Then the Big City bosses introduced the trading of jobs for votes and “taking care of people” and the corruption that came with them. In the South they had Plantation Politics, Jim Crow Laws, and a whites-only single party politics.

American political history is a real mixed bag. We can’t look to the past with rose-tinted glasses. Yet there was popular mobilization. Not in the 1920s when the Democratic candidates were more conservative than the Republicans. But with the Depression, FDR and the rejuvenation of the labor movement, there was real activism. Something was at stake — jobs, unemployment insurance, CCC [Civilian Conservation Corps]. There were real tangible rewards for political participation for ordinary folks, including poor people. Today the rewards are principally for the wealthy, the corporate representatives, what some would call the elite. And their participation is close to 100%.

Skeptic: The counter argument is that many people don’t vote because it really doesn’t matter. It takes a depression to generate that level of interest and participation. But those circumstances can also throw up revolutions of either the right or the left. Maybe the beauty of America is that we’re not overpoliticized or polarized.

Brown: No. That might have been true in the past. But prior to the 20th century there were turnouts of 75% to 80%. That was before women and African-Americans were allowed to vote. What you have now is the increasing manipulation of the people by the elite based on fear — fear of crime, of terrorism, and before that, of communism. We have the development of a garrison state and an invasive central power. Ironically this is often fostered by Republicans as well as Democrats under the rhetoric of “less government.” But the power of the government is getting greater and greater because it acquires newer technology and more money.

The non-participation of the people is really a misconception. The people are participating by their acquiescence. Consciously or not, they are being manipulated into demanding more and more police, surveillance, and incarceration, and the channeling of more money into the military and the corporate control of the economy. This is gradually diminishing the power of people, the strength of communities, the integrity of families and neighborhoods. We’re getting an almost ocean-to-ocean homogenized mass consumption culture that is kept in line by corporate advertising on the one hand and the police surveillance and incarceration of the few percent that can’t fit in on the other.

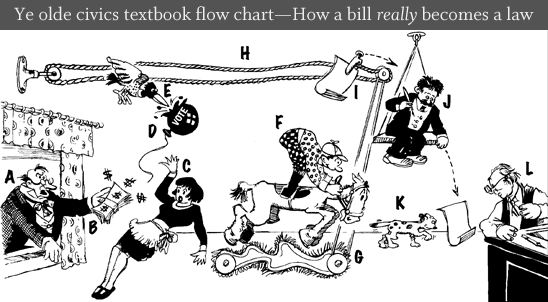

Skeptic: We’re all familiar with the flowchart in our high school civics book, “How a Bill Becomes a Law.” Now tell us how it really works.

Brown: The way it really works is that a lobbyist for some interest group — a trucking interest, sanitation interest, a union, a bank, or a savings and loan — will go to a legislator. If they’re in the game, they’ll know which legislator to go to and they’ll get a bill introduced. The interest group and its lobbyists will provide the language of the bill to the legislator. In California, the legislator will then have it written into the proper legislative language by the legislative council, a set of central staffers that serve the entire legislature. The bill then gets a number, and is ready to be reviewed by the various interest groups.

There as also public interest groups such as environmentalists, civil libertarians, and consumer advocates that push bills. And their bills are reviewed and often opposed by corporate groups that don’t want their business constrained.

But the real discussion goes on behind closed doors. It involves the contest of economic pressures and political forces. The public hearings are mostly for show. They serve to get publicity and to make the interest groups feel good.

Skeptic: How much of what we see of our legislatures on CSPAN and public access TV stations is for real and how much is professional wrestling?

Brown: Well, it’s professional wrestling in the sense that a lot of hearings take place just so the lobbyists can bring in their clients. It allows them to make a record, to put on a show, and to set out a marker so their boss will think they’re doing their job. If it’s a broad-based organization, they can send out a newsletter with a picture of all their experts testifying before Congress. It’s all kept in the massive Congressional Record. The whole thing is about making news and looking good. But the real work goes on privately, at the staff level particularly, and sometimes among the more experienced legislators.

But the key thing the legislators want to know is, “What do the interest groups think?” There are hundreds of these key interest groups. And they have to be satisfied. The word that we heard at the state capitol in Sacramento (CA) was, “the legislator is the horse and you have to deal with the jockey!” The jockey is the interest group. That’s where the power is. The necessary deals are cut. And they’re based on how they will get their guy elected, what will please the people in his or her district, usually the powerful people.

That’s not to say that a people’s group can’t have an impact. It can. But by and large, bills like the recent Telecommunications Bill are almost solely determined by the competing forces. Now, some people will say, “Well, it’s AT&T versus the Baby Bells versus the cable companies, and that’s democracy!” No! It’s competition among elite, unrepresentative power groups to carve up the public power of America for their own interest. That is not democratic in any sense.

Skeptic: If I’m a legislator why should I go along with these interests?

Brown: Because they provide the money for your campaigns. The corporations can also define the business climate or how it’s perceived. They are the powers-that-be. And if you become their enemy, you’re viewed as an odd ball, as ineffective. You don’t get re-elected. The PACs [Political Action Committees] provide an enormous sum of money. When the Democrats were in power, 50% of their money came from PACs. PACs deal with laws. That’s why they give money — to influence legislation. If you’re not part of that game, you’re not there. And since you are there, you’re part of the game. There are no exceptions.

Skeptic: What about the First Law of Politics, to wit, “If you can’t eat their food, drink their booze, screw their women, take their money, and then vote against them, you’ve got no business being here”?

Brown: That quote came from former California Assembly Speaker Jesse Unruh (aka “Big Daddy”). It’s another example of the way that politicians deceive themselves as well as their constituents, if in fact they do deceive themselves. The fact of the matter is that if day in and day out you take special interest money, you do what they want. Now on any given bill, if there’s heat, if there’s public scrutiny, you’re not going to be obvious about having been bought off. You have to keep that covered. But in fact you are bought off. The entire system is bought off by the institutional bias created by special interest campaign spending.

Skeptic: Who are the biggest contributors to the Republicans and the Democrats, nationally and here in California?

Brown: In each state it is a little different. Obvious examples come to mind. The truckers, the medical industry, the tobacco industry, some of the unions are big contributors.

Skeptic: Do they give to both sides?

Brown: A lot of them do; some don’t. Teachers and unions generally give to Democrats, oil companies and truckers are more Republican-oriented.

Skeptic: Perhaps you can define some of these “inside baseball” terms — what do they mean and why are they important: Soft Money.

Brown: Soft money is corporate or union, as opposed to individual, donations to a political campaign. In many states, there’s no legal limit on soft money. Legally it is not allowed in federal campaigns. It can only be used for voter registration, party building, and state campaigns. But it can funnel back into campaigns.

Skeptic: Vote Suppression.

Brown: When you engage in mudslinging you can lower the voter turnout and the reduction in voter participation is skewed against the poor. Inclination to vote is strongest among the most educated and the most affluent. As you go down the income and education scale, you find lower rates of participation.

Skeptic: Walking Around Money.

Brown: That’s money that you give to get people to go out and vote on election day. Today it’s principally in the poor neighborhoods of large Eastern cities.

Skeptic: Losers always like to claim the other side only won because they had more money. But if you’re interested in domestic or foreign policy, if you’re a group that has been the victim of government policies in the past, shouldn’t you contribute to the process? What’s wrong with that? Isn’t that simply playing by the rules and playing smart?

Brown: What’s wrong with it is that it offends common-law notions of bribery, which proscribe the giving or receipt of money or anything of value, where the intent is to influence official behavior. That pretty well describes campaign contributions, particularly PAC donations. What’s wrong is that the money exchange is inherently corrupting. It separates the process from ordinary people. As the central government takes on more power and as advanced technology makes things more complicated, the only ones with the time and the expertise to become active are the paid people. And increasingly they represent the corporate view of unlimited free trade, homogenization of all communities, the disruption of the neighborhood and the family in the service of neutered efficiency. Credit, consumption, global production, massive incarceration, massive propaganda, and a general anxiety are the products of the modern, market economy. It is making it virtually impossible to come to terms with the environmental crisis which threatens countless species, and human life itself.

Skeptic: Or are contributors in many cases just playing safe? To what extent are political contributions a subtle form of paying protection? If Skeptic magazine were in a position to make big contributions (unfortunately, we’re not) and there were a Gullible magazine, wouldn’t Gullible have to contribute just to “cover their ass” so Congress didn’t pass a bunch of pro-Skeptic legislation?

Brown: Well, buying protection is buying influence. You have to be in the game. If the Baby Bells don’t pay to play, then AT&T or the cable companies will come into their market and they’ll lose out. The government has power and it auctions it off in a sophisticated way. The skill of being a member of Congress is knowing how to play in that auction. And then it’s knowing how to take the money that comes from the auction and use it to get re-elected. That takes no brains at all because you hire a professional. You could be a dog and get elected, because most people don’t see their congressman. In the modern, anonymous, urban areas, it’s merely a mailer, a computerized pamphlet, brochure, book, or letter, and in some cases TV ads. But the face-to-face town meeting has long gone the way of the dodo bird.

Skeptic: Let me see if I can interest you in a deal. You be the liberal Democrat, I’ll be the conservative Republican. I’ll scare the hell out of businesses by saying that you’re going to raise taxes, and you scare the hell out of the unions by saying that I’m going to reduce their benefits. Don’t you and I have jobs for the rest of our lives where we don’t really have to work? Isn’t this a little like professional wrestling?

Brown: Right. That’s what it is. It’s a game. There are turf battles, however. There’s the Praetorian Guard that has to be fed. And then there are the congressmen and their staffs. And then there are the reporters who report on them. It’s becoming a semi-autonomous court, maybe like the court of Louis XIV or the Tsars of Russia. They throw a few bones to the people. They scare them with the hobgoblins of terrorism and underclass criminals. All of this is highly exaggerated. Much of it is created by the very corporate allocation of jobs and income, which then creates the dislocation and breakdown of the family, crime, and child abuse. All this generates the fear that keeps the same power mongers going in their decadent game of democracy abuse.

Skeptic: Now go back in time and put on your old hat as a working politico. I want to run for Governor of California. I’m hiring you as my consultant. How much will it cost?

Brown: It depends. Are you known or unknown? If you’re known, you need a lot less. When I ran in the late 70s it took a couple million. My sister ran in 1994 and spent $22 million and lost. But you could do it on a lot less.

Skeptic: Where does the money go?

Brown: It goes to television. Your opponent is going to say that “You are a dog molester.” Then you have to put on ads saying, “No, my opponent is a cat molester.” And it goes back and forth. If you’re not, as they say, “up on television,” people will ask, “Where are you? Have you dropped out?” You could be running around the state campaigning 10 hours a day. You have an electorate of 14 million in California. You can’t reach that many people face-to-face in a hundred lifetimes. You can only do it through the corporate media. And they charge as much as $30,000 per minute for a prime time ad in a major media market. So you’re talking about a million dollars a week to play in the game. Can you do that for $7 or $8 million? I think you could if you had a good campaign. You could do it for less if you had a real popular movement.

Skeptic: Do you, as the consultant, get commissions or rebates (i.e., kickbacks) on media buys and mailers?

Brown: You can get it on all of them. It all depends on what deal you cut or take. Today it’s much more “professional.” The consultants commission everything from the art work to the postage. They’re clever people. Consultants can be strategists or they can act as general contractors who haul in subcontractors. But it’s simple, straightforward stuff. You take a random sample and do a telephone poll. Then you produce your TV ads. Hollywood is crawling with film makers who want to sell their services. It’s a simple business. Some people have the knack for the game, just like some people can play football.

Skeptic: OK, I’m running as the Skeptical candidate. I’m skeptical that capital punishment really deters potential murderers, that increased school spending actually better educates students, that commuter lanes actually reduce pollution. My skepticism is such that I don’t think government ought to do anything unless there’s a clear and present danger if they don’t, and only after they have considered the unintended adverse effects of their policies. Do I stand a chance?

Brown: No. The whole government is part of the big corporate global economy. Without government policing everything from trademarks to highway congestion to pollution, the whole system will break down. If you just leave it to the corporations, everything will grind to a halt. Under the present system someone has to protect the property, the investments, the border. All that is managed by the government-corporate-media system.

Skeptic: Well, couldn’t you then at least whittle it down to just the cops and military?

Brown: Only if you whittle down the corporations. If you go back to the village, you could. But when you operate a global economy, bringing in tens of billions of dollars of merchandise from China, somebody’s got to keep all that straight. Who is going to police the people in China who copy CDs? That takes government. If you don’t police them, they’ll be selling them here in the U.S. We are ground into a world where the state is the integral element of the modern economy.

Skeptic: Would the public go for my platform, regardless of whether it’s practical?

Brown: No, because without government you wouldn’t have Social Security. People would die of food poisoning at some fast food joint. People want an answer. “If there’s a problem, let’s have a solution.” That is the media background music. If there’s child abuse, then thousands of people are arrested and millions are fingerprinted. It doesn’t matter that a few years later half of them have to be let out because they weren’t guilty. The war on drugs requires spending money in Mexico, Peru, Panama, and Colombia. And the money often goes to some of the same people working with the drug dealers to get the drugs in here.

The system is running out of control. It’s big, it’s hard to watch, and a lot of people would like to go back to simpler days. But they do like going to the mall and loading up their car with all the stuff. We live in an age of guilt-free consumption.

Skeptic: How about requiring TV (since that’s where most of the money goes) and radio stations, which have to be licensed to serve the public interest, to provide substantial free time to qualified candidates to use as they please?

Brown: That’s fine. I proposed that 20 years ago to the FCC. They never answered me, to this day, though some of the networks are now talking about it. You could create a public forum through television where we could have a vital, democratic process. But real reform will require more than just new rules for TV stations. It will require a change in attitudes that will produce a change in the structure of government. The financial incentive, which is the heart of capitalism, is now turning into an out-of-control engine that is destroying everything from the family to democracy to human freedom.

Skeptic: Originally, our legislatures met for only a small amount of time. They would then go home and lead a real life. We live in the age of high tech — internet, teleconferencing, telecommuting. Why do legislators have to be physically present to participate in debate and to vote? Why couldn’t they be given the option to do both remotely from their home office? This would allow voters in the district to see their representative far more frequently and make it much harder for a lobbyist to work all of them in one day. Why don’t we use technology in government more?

Brown: First, there is a fear of technology. Second, the players want to get together to establish their relationships, the mafia brotherhood. And they want to deal with the lobbyists to raise the money. They want to play in the game. The myth is the power of Washington, the power of the state capitol. That is the symbol that there is a deliberative process, a representative mechanism.

When politicians meet in official chambers it creates a ritual of government. Why do people have to go to church? The government is a church of a sort. The legislators voting in the Capitol is a way of ritualistically reconfirming the mythology that there is a democratic process to which the people are connected. The reality is very different.

Skeptic: As skeptics, we regularly hear from individuals who have left cults or fraudulent faith healing acts, and the comeback we always get from their erstwhile fellows is, “These are the people who have left. These are the sour grapes.” So, why shouldn’t we be skeptical of what you’re saying now?

Brown: Well, I said many of the same things when I was running for governor. I sponsored the Political Reform Act. If you listened to what I said at that time, it was not particularly different from what I’m saying now. But of course I didn’t really follow it.

Skeptic: What was the light that struck you on the road to Damascus?

Brown: Getting older, seeing the breakdown of our society, the increase in the number of homeless and poor, the quadrupling of incarceration — principally of poor people and people of color. And then seeing the growth of special interest money at the same time, the increasing professionalization and manipulation of the political process. All of that is making the political enterprise more and more unacceptable, at least to me.

Skeptic: From where you sit now, are you optimistic or pessimistic about the future of our republic?

Brown: I would say we face grave danger. Personally, I still have a certain optimism. That’s why I’m still involved.

Skeptic: Thank you for taking the time to speak so candidly with Skeptic. ![]()

Skeptical perspectives on economics and society

-

Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed

Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed

(paperback $17) by Jared Diamond

-

How the Economy Works: Confidence, Crashes,

How the Economy Works: Confidence, Crashes,

and Self-fulfilling Prophecies

(DVD $23.95 CD $15.95) by Dr. Roger E. Farmer

-

Dumbth and 81 Ways to Make Americans Smarter

Dumbth and 81 Ways to Make Americans Smarter

(paperback $22) by Steve Allen

NEW ON SKEPTICBLOG.ORG

What Do You Believe In?

Atheist are often asked what they believe in, in a tone implying that atheists cannot or do not believe in anything. In this week’s Skepticblog, Michael Shermer shares his answer to this question.