In this week’s eSkeptic:

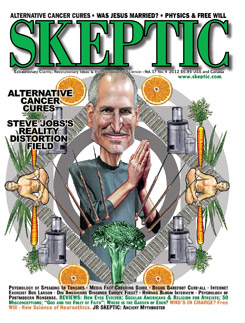

Illustration by Pat Linse from the cover of Skeptic magazine 17.4 (2012)

About this week’s eSkeptic

Apple Founder, Steve Jobs, had more than a knack for convincing anyone that seemingly unrealistic things were possible. In this week’s eSkeptic, Michael Shermer discusses how self-deception and a pervasive optimistic bias—Jobs’s “reality distortion field”—contributed both to his success and his demise.

This article appeared in Skeptic magazine issue 17.4 (2012).

The Reality Distortion Field

Steve Jobs’s Modus Operandi of Ignoring Reality is a Double-edged Sword

by Michael Shermer

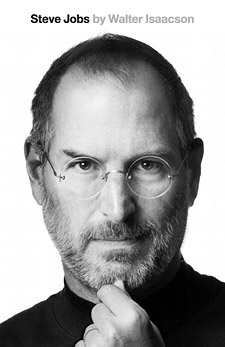

Robert Friedland was a long-haired, sandal-wearing, spiritual-seeking proprietor of an apple farm commune and student at Reed College when he met Steve Jobs in 1972 and introduced the future Apple computer founder to a principle called the “reality distortion field” (RDF). Friedland, Jobs recounted to his biographer Walter Isaacson in the 2011 biography Steve Jobs (Simon and Schuster) published shortly after Jobs’s death, “turned me on to a different level of consciousness.” The feeling was apparently mutual. “The thing that struck me was his intensity,” Friedland recalled about Jobs. “Whatever he was interested in he would generally carry to an irrational extreme.” Staring, for example. “One of his numbers was to stare at the person he was talking to,” Freidland noted. “He would stare into their fucking eyeballs, ask some question, and would want a response without the other person averting their eyes.”

The reality distortion field was a bubble Jobs lived in that shielded him from the normal fears that held back so many others. “According to another Reed student and early Apple computer employee named Elizabeth Holmes, “If he’s decided that something should happen, then he’s just going to make it happen.” And the effect was contagious, she continued. “If you trust him, you can do things.” Macintosh software designer Bud Tribble agreed: “In his presence, reality is malleable. He can convince anyone of practically anything. It wears off when he’s not around, but it makes it hard to have realistic schedules.” The origin of the “reality distortion field” was the original pilot episode of Star Trek, “Menagerie,” Tribble explained, “in which the aliens create their own new world through sheer mental force.” And just as in that episode such power cuts both ways. As Holmes explained: “It was dangerous to get caught in Steve’s distortion field, but it was what led him to actually be able to change reality.”

Another Mac software designer named Andy Hertzfeld expanded on the concept as it was employed by Jobs: “The reality distortion field was a confounding mélange of a charismatic rhetorical style, indomitable will, and eagerness to bend any fact to fit the purpose at hand.” The first Mac team manager Debi Coleman said Jobs “reminded me of Rasputin. He laser-beamed in on you and didn’t blink. It didn’t matter if he was serving purple Kool- Aid. You drank it.” And yet when the power was properly channeled, “You did the impossible, because you didn’t realize it was impossible.” The RDF was more than an on the job placebo effect, as Hertzfeld noted: “Amazingly, the reality distortion field seemed to be effective even if you were acutely aware of it. We would often discuss potential techniques for grounding it, but after a while most of us gave up, accepting it as a force of nature.” Eventually the phrase was sloganized on T-shirts after Jobs replaced the soft drink sodas in the company fridge with healthy Odwalla organic carrot and orange juices. On the front of the T-shirt it read “Reality Distortion Field.” On the back, “It’s in the juice!”

Even Jobs’s Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak experienced Jobs’s power: “His reality distortion is when he has an illogical vision of the future, such as telling me that I could design the Breakout game in just a few days. You realize that it can’t be true, but he somehow makes it true.” Jobs himself described it through the words of the White Queen in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass: “Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.”

Some of Jobs’s colleagues were less impressed, seeing the RDF as little more than deception. Macintosh graphic designer Bill Atkinson, for example, told Isaacson “He can deceive himself. It allowed him to con people into believing his vision, because he has personally embraced and internalized it.” Isaacson qualified the harsh judgment, noting “But it was in fact a more complex form of dissembling. He would assert something—be it a fact about world history or a recounting of who suggested an idea at a meeting—without even considering the truth. It came from willfully defying reality, not only to others but to himself.”

A deeper explanation for the reality distortion field and its effects may be found in evolutionary theory and in what Robert Trivers calls “the logic of deceit and self-deception” in his 2011 book The Folly of Fools (Basic Books). Here’s the logic of how it works: A selfish-gene model of evolution dictates that we should maximize our reproductive success through cunning and deceit. Yet game-theory dynamics shows that if you are aware that other contestants in the game will also be employing similar strategies, it behooves you to feign transparency and honesty and lure them into complacency before you defect and grab the spoils. But if they are like you in anticipating such a shift in strategy they might pull the same trick, which means you must be keenly sensitive to their deceptions and they of yours. Thus we evolved the capacity for deception detection, and this led to an arms race between deception and deception detection.

Deception gains a slight edge over deception detection when the interactions are few in number and among strangers, but if you spend enough time with your interlocutors, they may leak their true intent through behavioral tells. As Trivers notes, “When interactions are anonymous or infrequent, behavioral cues cannot be read against a background of known behavior, so more general attributes of lying must be used.” He identifies three: (1) Nervousness. “Because of the negative consequences of being detected, including being aggressed against…people are expected to be more nervous when lying.” (2) Control. “In response to concern over appearing nervous…people may exert control, trying to suppress behavior, with possible detectable side effects such as…a planned and rehearsed impression.” (3) Cognitive load. “Lying can be cognitively demanding. You must suppress the truth and construct a falsehood that is plausible on its face and…you must tell it in a convincing way and you must remember the story.”

Cognitive load appears to play the biggest role. “Absent well-rehearsed lies,” Trivers explains, “people who are lying have to think too hard, and this causes several effects,” including over control that leads to blinking and fidgeting less, using fewer hand gestures and longer pauses and higher-pitched voices. As Mr. Lincoln well advised, “You can fool some of the people all of the time and all of the people some of the time, but you cannot fool all of the people all of the time.” Unless self-deception is involved. If you believe the lie, you are less likely to give off the normal cues of lying that others might perceive, and thus the logic of how deception and deception detection creates self-deception. The reality distortion field is a type of self-deception that Jobs was able to employ to bolster the hopes and dreams of both himself and those around him to push through the normal barriers that hold most of us back when we are forced to suffer the slings and arrows of life’s outrageous fortune so that we may take arms against a sea of troubles.

To that end, the reality distortion field is also an extreme version of what the psychologist Daniel Kahneman calls a “pervasive optimistic bias” in his 2011 book Thinking, Fast and Slow (Farrar, Straus and Giroux). “Most of us view the world as more benign than it really is, our own attributes as more favorable than they truly are, and the goals we adopt as more achievable than they are likely to be,” Kahneman notes. For example, only 35% of small businesses survive in the U.S., but when surveyed 81 percent of entrepreneurs assessed their odds of success at 70%, and 33% went so far as to put it at 100%! “One of the benefits of an optimistic temperament is that it encourages persistence in the face of obstacles,” Kahneman notes. But over-optimism can backfire, making one blind to cues that failure is imminent and it’s time to cut your losses and get out. In a research project conducted by Duke University professors who collected 11,600 chief financial officers forecasts and matched them to market outcomes, CFOs “were grossly overconfident about their ability to forecast the market.” In point of fact, the correlation between predictions and outcomes was less than zero! And this overconfidence can be costly, Kahneman explains: “The study of CFOs showed that those who were most confident and optimistic about the S&P index were also overconfident and optimistic about the prospects of their own firm, which went on to take more risk than others.”

Inventors are high risk takers who need a lot of self-confidence to survive the rough and tumble world of creative competition, but in a Canadian study Kahneman cites 47% of inventors participating in the Inventor’s Assistance Program in which they paid for objective evaluations of their invention on 37 criteria, “continued development efforts even after being told that their project was hopeless, and on average these persistent (or obstinate) individuals doubled their initial losses before giving up.” The key is in the adjectives. Persistence is one thing, obstinance is quite another. In this case, failure may not be an option in the minds of entrepreneurs (and NASA flight directors), but it is all too frequent in reality, which is why another bias called “loss aversion” is felt by most.

The principle of loss aversion dictates that we fear losses twice as much as we look forward to gains. In gambling on the stock market, for example, we should keep loss aversion in mind when we are thinking about selling a losing stock but hesitate because we don’t want to feel the pain of a loss. On the other hand, loss aversion can cause some investors to get out during a rough-and-tumble stretch in the stock market, instead of riding it out and cashing in on those big comeback days. And loss aversion is related to another psychological principle in behavioral economics called the endowment effect, where we are more willing to invest in defending what is already ours than we are to take what is someone else’s. Dogs, for example, will invest more energy in defending a bone from a challenger than they will in absconding with some other dog’s bone. Together, loss aversion and the endowment effect show how evolution has wired us to care more about what we already have than what we might possess. High risk takers such as entrepreneurs seem better able to override the loss aversion emotion, and in moderate doses this can lead to success. Over-optimism to the point of distorting reality can lead one to take unnecessary risks, dangerous risks, and even deadly risks, as we’ll see in the case of Jobs.

Jobs’s optimistic bias was off the charts. According to Isaacson, “At the root of the reality distortion was Jobs’s belief that the rules didn’t apply to him. He had the sense that he was special, a chosen one, an enlightened one.” Andy Hertzfeld added: “He thinks there are a few people who are special—people like Einstein and Gandhi and the gurus he met in India—and he’s one of them. Once he even hinted to me that he was enlightened. It’s almost like Nietzche,” referencing the German philosopher’s concept of the Überman’s “will to power” from Thus Spoke Zarathustra: “The spirit now wills his own will, and he who had been lost to the world now conquers the world.”

Jobs’s self-importance and will to power over rules that applied only to others were reflected in numerous ways: legal (parking in handicapped spaces, driving without a license plate), moral (accusing Microsoft of ripping off Apple when both took from Xerox the idea of the mouse and the graphical user interface), personal (refusing to acknowledge paternity of his daughter Lisa even after an irrefutable paternity test), and practical (besting resource-heavy giants IBM and Xerox in the computer market with a fraction of their budgets). Jobs’s RDF unquestionably contributed to his success in revolutionizing no fewer than six industries: personal computers, animated films, digital music, cell phones, tablet computing, and digital publishing. He started a business in his parents’ garage that became the world’s most valuable company. He changed the world, and to that end his reality distortion field served him well.

There was, however, one reality his distortion field could not bend to his will: cancer. In 2003 Jobs was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, which further tests revealed to be an islet cell or pancreatic neuroendrocrine tumor that is treatable with surgical removal, which Jobs refused. “I really didn’t want them to open up my body, so I tried to see if a few other things would work,” he later admitted to Isaacson with regret. Those other things included consuming large quantities of carrot and fruit juices, fasting, bowel cleansings, hydrotherapy, acupuncture and herbal remedies, a vegan diet, and, says Isaacson, “a few other treatments he found on the Internet or by consulting people around the country, including a psychic.” They didn’t work, and in the process we find the alternative medicine question, “What’s the harm?,” answered in the form of an irreplaceable loss to humanity.

Out of this heroic tragedy a lesson emerges—reality must take precedence over willful optimism, for nature cannot be distorted. ![]()

Alternative

Cancer Cures

In this issue: Steve Job’s Reality Distortion Field; Media Fact Checking Guide; Bogus Barefoot Cure-all; Internet Exorcist Bob Larson; Did Americans Discover Europe First?; Howard Bloom Interview; Psychology of Postmodern Nonsense. Reviews: How Eyes Evolved; Secular Americans & Religion for Atheists; 50 Misconceptions; “God and the Folly of Faith”; Who’s in Charge? Free Will; New Science of Neuroethics. Junior Skeptic: Dark Secrets of the Oracle-Monger, more…