In my last post I outlined a small recent stir caused by sharp comments about skeptics from former Ghost Hunters cast member Amy Bruni. I promised to dig further into the issues of skeptical undercover work and “sting”-type traps designed either to expose the roots of claims or, in the most striking cases, to catch charlatans red-handed.

These tactics can be extremely hard hitting, when they hit their mark. A well-known case involving both deceptive undercover work and a shocking reveal is “Project Alpha,” organized by James Randi. Under his direction, teenaged magicians Steve “Banachek” Shaw and Michael Edwards posed as psychics in a laboratory setting, where they successfully bamboozled parapsychological researchers. When the skeptical conspirators eventually held a press conference and revealed their years of deception (video), the world was compelled to consider parapsychology’s vulnerability to fraud. The ripples from that hoax are still being felt, as Randi’s contemporary Ray Hyman predicted more than 30 years ago: “There’s going to be an argument from now until doomsday about what the whole thing showed.” Another classic example of a skeptical sting is the operation which severely set back the profitable faith healing career of Peter Popoff in 1986 (also spearheaded by Randi, in collaboration with the Houston Society to Oppose Pseudoscience, the Society of American Magicians, and the Bay Area Skeptics). The televised exposure of Popoff’s secret use of “miraculous” information relayed by radio surely stands one of the greatest “gotcha” moments of all time (video).

Such cases can inspire an exuberant emotional satisfaction in skeptics—in me!—but critics rightly point out that these tactics are also ethically complex. They may involve deception, or at very least sneakiness, typically without any oversight whatsoever. They may erode trust between communities that could use each other’s help. They may cause skeptics to appear untrustworthy or unprofessional. Stings may cross lines of privacy. They may expose their targets to ridicule, career damage, financial hardship, or even, conceivably, prosecution, harassment, or violence. Who decides which targets “deserve it”? In any event, inflicting or risking these harms ought to be a weighty matter. What toll might it take on vulnerable followers when a faux-psychic spiritual leader is exposed? When might such debunking further entrench delusional beliefs? Nor are underhanded tactics available only to “the good guys” we might like to see use them, or only to those who might use them responsibly. Sloppy or prematurely attempted exposés may inflict damage on people without sufficient cause or on the basis of poor evidence. Or, such missteps may give swindlers the upper hand, gifting them the opportunity to claim vindication or persecution. Unscrupulous work in this “gotcha” mode may unleash the dogs of public shaming, or even the punitive power of the state, on targets who clearly do not deserve it—sometimes misleading the public in the process. (“Climategate,” anyone?) Some such tactics may even run afoul of the law. For all these reasons, skeptical stings have always been controversial.

That recurring controversy has flared up again over the last few days with Bruni’s remarks. Her comments seem to have been sparked by sting projects dubbed “Operation Bumblebee” and “Operation Ice Cream Cone” by organizer Susan Gerbic. Those projects seem to me to be interesting recent contributions to a very old tradition, but it’s the tradition itself—the use of these concepts through history—that I’m interested in exploring today.

Bruni’s complaints suggest two related questions. Should false claims in the paranormal realm be identified and the truth about them revealed? And, if so, what methods may be justifiably used to accomplish that end?

Like most skeptics, I’m of the opinion that the answer to the first question is “Yes, debunking is an essential component to the search for knowledge.” I would argue further that paranormal proponents ought to feel the same way. In a response to Bruni at the Skeptic’s Boot blog, blogger Robert Lea offered an opinion about skeptical exposés which echoes a point I have frequently made myself:

You then move on to the subject of skeptical activism. I have a quite strong stance on this. Believers should not be opposing skeptical activism, they should be WHOLE HEARTEDLY SUPPORTING IT.

There is absolutely no doubt that there are frauds and charlatans at work in the paranormal field. Even the strongest believer would have to admit that there those in the field who are claiming such skills and abilities falsely for the purpose of extracting money from others. If you are a believer surely you would want these fraudsters exposed?

One would indeed think so, and, thankfully, one would to some extent be right.

Paranormal Believers as ‘Gotcha’ Debunkers

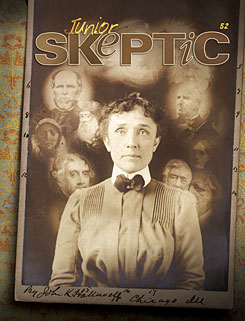

The psychical research, Spiritualist, and parapsychology communities all have proud traditions—rarer than they should be (perhaps much rarer), but proud nonetheless—of mounting effective critiques of paranormal claims and fraudulent psychics, sometimes involving “gotcha” exposés. Consider, for example, Walter Franklin Prince‘s 1919 demolition of supposed spirit photographer William Keeler, whom Prince caught re-using the exact same two photographs of one man to create thousands of bogus spirit photographs for a grieving client. (See the original Proceeding of the American Society for Psychical Research paper here in PDF, courtesy of the International Association for the Preservation of Spiritualist and Occult Periodicals; see Junior Skeptic 51–52 for more on this case and the discreditable history of spirit photography.)

On the face of it, efforts to expose fraud should be firm common ground for skeptics and proponents. Both groups agree that fraud exists, especially in the shadowy realm of commercial psychic services. Criminal convictions for heartless faux-psychic confidence artists are depressingly routine (though not nearly so routine as they should be). We all know too that fraud makes psi research look bad. Identifying bad apples should be an urgent priority for everyone who hopes to move psychic research into the mainstream. As celebrated psychic proponent Arthur Conan Doyle put it in regard to the regrettable phenomenon of the fake medium, “We are all out to get that scoundrel, and ready to accept any honest help in our search for him.”

“That scoundrel” has given generations of psychical investigators ample reason for caution. As a result, an undercover element has been common throughout the history of pro-paranormal investigation of psychic claims, just as it has in the skeptical tradition. To rule out the ever-present possibility of hot reading, investigators have very frequently attempted to anonymize or obscure their identity when visiting a psychic, either by not giving a name or by giving a false one. This was the precaution taken by former First Lady of the United States Mary Todd Lincoln, for example, when she adopted the name “Mrs. Lindall” for her visit to the commercial studio of pioneering spirit photographer William Mumler. Nonetheless, Mumler soon conjured up the likeness of the late President, while Mumler’s wife, a medium, spoke in the voice of Mrs. Lincoln’s deceased son Thaddeus. Mrs. Lincoln’s minor deception had been a good idea, but in her case it was also naive. It was not realistic for Abraham Lincoln’s widow, one of the most famous Spiritualists in the world, to believe she could move unnoticed through the for-profit psychic scene. (On the other hand, skeptic Mark Twain’s visit to a London phrenologist “under a fictitious name” was more effective, despite his fame. Unrecognized, he was told his skull had a rare “cavity” where his sense of humor should be. Returning three months later under his own name and occupation, Twain learned, he said, that the “cavity was gone, and in its place was a Mount Everest—figuratively speaking—31,000 feet high, the loftiest bump of humor he had ever encountered in his life-long experience!”) Similarly naive were hopeful believers who took care to arrive at a psychic’s place of business unannounced and pseudonymous—after being urged to go there at a particular time by another medium who was already intimately familiar with their sorrows and circumstances.

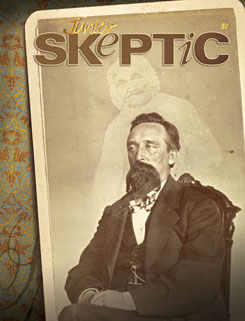

See Junior Skeptic #52 for the story of Charles Williams and other audacious scoundrels connected to the practice of spirit photography in Europe.

Sometimes exposés of fraudulent psychics by believers have involved methods dramatically more aggressive—even violent—than any skeptic would advocate today, such as physically grappling with or restraining supposed “apparitions” during seances. Here, for example, is an account of the forcible 1878 unmasking of mediums Charles Williams and A. Rita by Spiritualists in Amsterdam. (“Charlie” in the passage below was a spirit character allegedly manifested by Rita; “John King” was a quite famous spirit manifested by Williams. Emphasis added):

At once one of the sitters near the cabinet made a leap, grasped Charlie, and caught the collar of Mr. Rita’s coat. A struggle ensued in perfect darkness. The gentleman cried out, “I hold the medium,” and others entered the cabinet to assist in catching the two struggling mediums. Heavy blows were given and received, and furniture was broken. As at last a light was struck, the two mediums tried to escape out of the room, but luckily the lady of the house had shut the front door, so that they were again seized, and brought into the room and searched, notwithstanding their courageous powers of defence, for some of the gentlemen who held them can give proof of their muscular force. Williams, chiefly, was foaming with rage. Rita resisted less. The following objects were found on the mediums, but hidden between their clothes, shirts, pockets, &c.

On Rita, a reddish-grey, nearly new beard (Charlie’s); three large handkerchiefs, one of them of muslin; …a bottle of phosphoric oil…convincing us that the light of Charlie was nothing else.

On Williams, a black beard (very old, dirty, and used) sewed on brown silk ribbons (John King’s) ; several yards of dirty, soiled, and very frequently used muslin; some muslin handkerchiefs, which served without doubt as John’s turban, &c.; a bottle of phosphoric oil….

Amazingly, Williams tried to brazen through this stark exposure. “I am innocent,” he solemnly assured the Spiritualist press, asking “all those who know me, to consider whether it is at all feasible that I, who have stood the test of public mediumship, including the stringent tests of scientific men, for at least eight years, should have occasion to play the part of a trickster.” Well, yes, pal. It is indeed feasible.

No honest conversation can take place on the topic of the paranormal that does not begin with the fact that audacious and clever fraud does quite commonly occur. Moreover, proponents ought to face frankly the frequency with which frauds have gone undetected—or worse, noticed but explained away—until they were finally revealed in caught-red-handed exposés so shocking that excuses were no longer reasonable. (Excuses are nonetheless made even in such extreme cases. Bizarrely, these excuses are frequently still accepted by the psychic performer’s dedicated fans.)

Debunking By Trap

I grew up watching esteemed paranormal sleuth Fred Jones set traps to expose spooky characters every day after school. But the idea of exposing Old Man Jenkins’ real world counterparts through means of conceptual snares is much older and more realistic than cartoons suggest. Indeed, the history of debunking traps extends so far back into antiquity that their origin is lost in myth.

One such trap is described, for example, in the Bible’s Book of Daniel. In the story (canonical in some Christian traditions, apocryphal in others) Daniel is presented with a paranormal mystery: a statue of the god Bel is believed to perform the nightly miracle of consuming a vast feast of offerings (“twelve bushels of the finest flour, forty sheep and six measures of wine”). Daniel laughs at this claim. “Do not be taken in,” Daniel tells the king in a bit of busy-body skeptical activism, for the statue is “clay inside, and bronze outside, and has never eaten or drunk anything.” The king decrees that the claim be put to the test. Bel’s priests suggest a seemingly definitive trial: the king will personally lock and seal the doors of the temple after the feast is set out. If the feast is consumed as usual within its locked room, the king will surely have his answer. But Daniel is not willing to rely upon the conditions proposed by the claimants. He conceives a second, secret test—the real test, a trap deceitfully laid in order to capture the truth. Before the doors are sealed, and unknown to the priests, Daniel secretly scatters ashes across the floor. When examined the next morning, these ashes tell the true story of Bel’s miracles: they record the footprints of the deceitful, free-loading priests and reveal the location of their concealed entrance. Gotcha. (This story ends poorly for the scammers.)

It is worth emphasizing that while the story of Daniel and Bel may be legendary, it describes a practical investigative approach. Daniel’s trick with the ashes is fundamentally identical to “a little harmless test” described in 1887 by one of the investigators for the University of Pennsylvania’s Seybert Commission into mediumistic phenomena. Testing a medium whose spirits typically played musical instruments, the investigator secretly applied “a dab of printer’s ink on one of the drumsticks at the very last moment before the séance began.” Through this subterfuge, the medium was caught ink-handed, indelibly marked with the evidence of his deception.

Fifteen Hundred Husbands

The tactic of feeding fictional information to psychics also goes back to antiquity. Second century Roman satirist and debunker Lucian of Samosata, for example, fed misleading clues to the psychic cult-leader Alexander of Abonoteichus in the hopes that Alexander would incorporate these into his readings. “Many such traps, in fact, were set for him by me and by others,” Lucian wrote—and these deceptions worked. Alexander took the bait, just as so many psychics have done since. (See Junior Skeptic #45.)

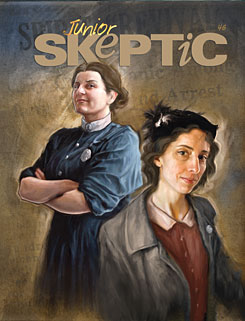

See Junior Skeptic #46 to learn about the careers of skeptical private investigator Rose Mackenberg and NYPD detective Mary Sullivan.

Assuming a fictional identity with fictional personal and relationship details was private investigator Rose Mackenberg’s standard first step when investigating psychics from the 1920s to the 1950s. But she did not stop with that modest deception. As an activist skeptic, her understanding and attitudes were much the same as activist skeptics today; as a professional detective working in another time, however, her techniques and sense of ethical boundaries were quite different.

Here is how she described one case in 1939. When a wealthy industrialist identified pseudonymously as “Mr. Todhunter” lost thousands gambling on tips from a “psychic” named Mr. Charles, Mackenberg was hired to get to the bottom of it (emphasis added):

I arrived the next day. My first step was to attend one of Mr. Charles’ seances myself. Sure enough, this time an elderly woman was waiting in the ante-room and, as Wilson had done to Todhunter, she engaged me in conversation, told me how Mr. Charles’ advice had helped her straighten out a difficulty with her husband, and helped her marry off her daughter to a rich man. In turn I told her that my husband had died recently and that I was worried about the health of our child—incidentally I have never been married, but in my career as a spook detective I have received messages from about 1,500 husbands and 3,000 children. When I finally got in to see Mr. Charles I was not surprised to hear he was in touch with my dear, departed husband, or to be told that my child was passing through a dangerous period. As a lure for more $25 fees, Charles had my husband’s spirit urge me to keep in touch so that our child could get the benefit of advice from the other world. However, my visit was not wasted. I confirmed the fact that Mr. Charles’ technique included the use of stooges in his ante-room. And I located a good place in his inner sanctum to install a dictograph. My assistant put it in that night. Meanwhile, another associate of mine had shadowed Wilson all day. He learned, without surprise that Wilson was also a steerer for a local gambling joint, the very same in which Todhunter bad lost his $8,000. The conversations we recorded between Wilson and Charles during the next three days proved all we needed to know about the conspiracy.

Mackenberg went on, “I shall never forget the beet-red of Todhunter’s face when Charles’ voice squeaked from the horn: ‘He doesn’t suspect a thing. I wonder how that sucker manages to come in when it rains, let alone run a business. He’s as innocent as a baby, and twice as stupid.’”

Make no mistake: some psychic readings are neither paranormal phenomena nor entertainment, but crime. When law enforcement agencies investigate criminal fraud on that level—intentional, callous, and sometimes very organized—they may deploy tools that modern skeptics do not have, such as warrants to search, seize, or surveil. The tools left to modern skeptics, journalists, and paranormal researchers are weaker. Scholarship is of course the biggest, most important, and morally cleanest tool we have, whether that scholarship involves the sleuthing of the reporter, the plausibility assessment of the scientist, or the perspective of the historian. But the most potent investigative tool available to civilians, at least in applicable cases, is the undercover sting. Nothing demonstrates like a demonstration.

Ethical Implications

Stings, traps, and undercover investigation have always played an important role in skeptical paranormal research—in my view, an indispensable role. Without these tactics, we would never have learned the things we know about paranormal fraud.

But shouldn’t skeptics—ostensibly activist truth-tellers—feel ethically troubled by this business of investigating by deception?

Yes. Hell yes. Of course we should. The very existence of the skeptical movement is based upon the sentiment that deception is a big deal.

And look—the organized project of scientific skepticism may be decades old (and the debunking genre much older), but, by and large, the practice of skepticism remains an amateur, fledgling affair. We lack the kinds of institutions, regulations, legal precedents, and social norms that allow other fields to attempt responsible use of deception for the public good.

“Every undercover operation involves ‘deception,’ which has long been a critical tool in fighting crime,” said Federal Bureau of Investigation Director James Comey in 2014. But, he went on, “The F.B.I.’s use of such techniques is subject to close oversight, both internally and by the courts that review our work.”

Lay skeptics are sure as hell not the FBI. So what are we? Are we scholars? Reputable investigators? Vigilantes? How can we even tell the difference? And if we’re not sure, can we really blame our counterparts in the paranormal community if they can’t tell either?

Law enforcement officers have oversight. Psychologists have to navigate ethics review committees before they mislead subjects. Undercover reporters have editors, institutional standards, case law, and the massive weight of journalistic tradition. Even private investigators have professional organizations with codes of conduct (and in most US States, they must also be licensed). What do skeptics have? What standards guide us when we get it into our heads as artists, bloggers, magicians, or grassroots activists to catch someone at something? We go in naked and unsupported, armed with our conscience and whatever the audience will accept in the mood of the moment—and very little else. Skeptics have no established code of ethics, no overarching professional organizations, no mechanisms for censure or oversight or review. We have a sense of righteous cause, and sometimes a sense of wicked enemies. And that, my friends, is a recipe for trouble.

So what do we do about it? How do we get at truths that are intentionally and cleverly hidden, sometimes literally by criminals, while also hashing out and working within some sort of reasonable ethical boundaries? I don’t know the answer. I do know that this is the hard part. This is where trickery gets trickier.

If you learn that someone’s publicly pronounced ideas have been put in some discomfort, or that the TV proponent of the paranormal has been offended, you’ve only done half the work; you can’t call the cause unethical until you weigh the countervailing value.

Public actors in these fields (I don’t need to define “these fields”, do I?) are not people who harmlessly “hold these beliefs”. Whether in good faith or not, whether ghosts exist or not, they adversely influence humanity by protecting and promoting superstition and deleterious habits of thought. Superstition and pre-enlightenment habits of thought retard human progress – always, and are worth striving against – always. We’re not dragging Aunt Millie off the couch, into the public square to berate her paranormal beliefs – these are public actors.

Science is all about “sting” operations. You test a hypothesis by trying to “fool it.” If you can’t, the hypothesis stands.

No one claiming supernatural power has anything to fear from these operations. If a performer truly has powers, no sting in the world will be able to catch them using trickery.

I don’t see such operations as activism, but rather as research. The conclusion can’t be known ahead of time. Given the drastic decline of large skeptic organizations, I’m glad there’s some activity from the grassroots taking place.

FBI and law enforcement have oversight because their investigations send people to prison or to death. It is the State working in an official capacity using great powers not held by anyone else. It is not because deception is so intrinsically awful that any form of it requires a grand jury to parse the ethical minutia.

To be clear, I’m in favor of undercover work by the FBI and skeptics both. I’d like both to put quite a bit of effort into parsing the “ethical minutia,” though.

I think discussing effectiveness and methods is important.

What good is being active if what you’re active doing isn’t effective. What good is being active if you font evaluate and improve your methods.

Running around randomly screaming “this guy is a fraud” is being active, but I don’t think it is as effective as a well organized protest.

I find it disheartening that, after all the hard work we put into this, the conversation that emerged is “are these people unethical?” rather than, “are these people scamming their victims by claiming to be psychics and clairvoyants?”

And no, I’m not saying that the former is unimportant, or even that I have the answer to the question. I’m just saying that we should spend 30 seconds congratulating Susan (and perhaps the rest of us?) for shedding light on a problematic situation, and hopefully encouraging others to get ACTIVE.

Like I say in the post, this is a general discussion. It should not be read as a review of those specific projects. They’ve received a fair bit of coverage, I’m happy to note, including the two pieces by Susan which I link to above, and your own piece at the JREF, which I read with interest last year. My purpose here is different. I write often on the history, conceptual foundations, and ethics of skepticism. This post is meant to continue those wider conversations.

IMO, what matters more than whether or not something can be classified as a “sting” operation is how that operation was planned and conducted, the outcome, and how all of it is communicated.

The bottom line is that there are legal, moral, ethical, and practical implications of just about every activist endeavor. We are never on the right side of those issues just because we claim to be, and there is no institutional oversight. Skeptic activists should not only take great care in conducting such work, but they should view criticism in these areas as opportunities–to learn and grow, or even to defend the work.

Martin Gardner’s New Age: notes of a fringe watcher contains a pretty good justification for sting operations it occurs to me.