12-03-14

In this week’s eSkeptic:

About this week’s eSkeptic

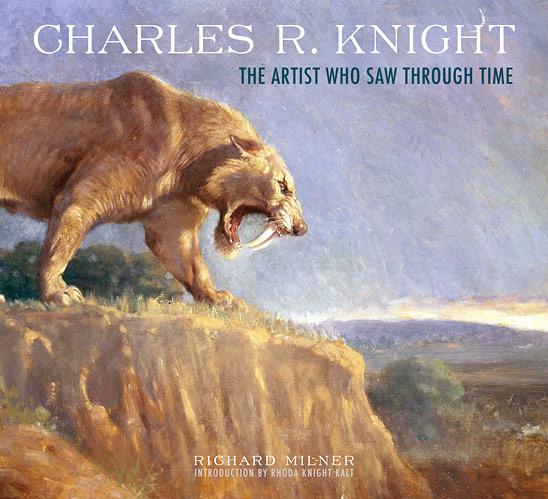

In this week’s eSkeptic, Donald R. Prothero reviews Richard Milner’s new book, Charles R. Knight: The Artist Who Saw Through Time (Order the book from Amazon). The review copy of this book was so popular in the Skeptics Society office that everyone wanted it! (All images below are protected by copyright and used with permission.)

The Father of “Jurassic Park”

a book review by Donald R. Prothero

Anywhere you go in modern society, dinosaurs are ubiquitous. From the movies to TV to the internet to toy stores and museum gift shops, there are countless chances to spend money on dinosaur paraphernalia. The three Jurassic Park movies were among the top grossing movies of all time. For kids between the ages of 2 and 12, dinosaurs are often a major part of their imaginations. Many kids are hugely fascinated with them, and have learned to master their polysyllabic names to the amazement of their parents. (I was one of those kids, hooked on dinosaurs at age 4. I wanted to become a paleontologist as soon as I knew what the word meant. Back in the late 1950s–early 1960s when I grew up, this was highly unusual; kids back then didn’t care much for dinosaurs compared to today’s kids). Most kids change their interests as puberty hits and they enter the “tweens” and teen years, but the fascination with dinosaurs never completely disappears.

Charles R. Knight in a 1935 publicity photo for his book Before the Dawn of History.

Colorized by Viktor Deak. © Richard Milner. (Click image to enlarge)

We can’t imagine a world where this is not true, but in fact it is a relatively recent phenomenon, just a century old. More than any other person, the public fascination and interest in prehistoric creatures owes its existence to one man, Charles R. Knight. Prior to Knight’s “reconstructive” illustrations of a wide range of extinct animals, there was almost no public awareness of them.

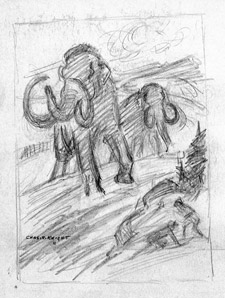

Rough sketch suggests one of Knight’s favorite themes: the puny but clever humans taking on impossibly huge prey, such as these woolly mammoths. © Rhoda Knight Kalt.

(Click image to enlarge)

The earliest discoveries of dinosaurs in Britain in the 1830s and 1840s were just fragmentary bones, and by the 1860s they had been depicted as giant lizards by the British artist Waterhouse Hawkins. In the U.S., the early discoveries by Joseph Leidy, O. C. Marsh, and Edward Drinker Cope were also quite fragmentary, and illustrated only in technical monographs that the general public could not obtain. There were almost no museums displaying large mounted skeletons of dinosaurs until Henry Fairfield Osborn of the American Museum of Natural History in New York did so in the early 1900s. Osborn’s museum crews obtained nearly complete skeletons of some of the most famous dinosaurs: sauropods like “Brontosaurus” (now Apatosaurus) and the first skeletons of Tyrannosaurus rex and Triceratops. Osborn realized the publicity value of spectacular dinosaur skeletons for his growing museum, and so these mounts were the forerunners of the many displays in museums worldwide. But mounted skeletons were not enough. Osborn realized that the “dry bones” did not speak to the public so clearly without a good reconstruction to help the layperson visualize them. And fortunately for paleontology and history, he discovered the gifted young Charles R. Knight hanging out with the taxidermists at his museum.

Knight’s favorite painting, the tiger and peacock, which he refused to part with during his lifetime, is now being offered by an art gallery. © Rhoda Knight Kalt. (Click image to enlarge)

As this outstanding book by historian of science Richard Milner describes it, Knight was born in Brooklyn in 1874, three years after Darwin published The Descent of Man. This was a period of groundbreaking discoveries in biology and paleontology, and young Charles was fascinated with animals as a toddler. One day he told his father he was tired of stories about Jesus, and wanted to hear stories about elephants! He began doing sketches of the animals in his books, even though he lived in urban Brooklyn with few exotic animals to study. Eventually, naturalists such as Osborn, Theodore Roosevelt, and the wealthy “sportsmen” of the Boone and Crockett Club established the Bronx Zoo. Here, Knight got his first chance to practice his burgeoning art skills on drawing animals from all over the world. Unfortunately, when Charles was 6, he was struck by a pebble thrown by another boy, and it damaged his right eye. He had to use his myopic and astigmatic left eye for the rest of his life, and somehow managed to produce his greatest work during his later years when he was legally blind!

Knight’s fast-moving, acrobatic Dryptosaurs do battle, in this classic 1897 painting known to dino buffs as “Leaping Laelops.” © AMNH. (Click image to enlarge)

Charles’s father was a secretary to J.P. Morgan, powerful baron of industry and treasurer of the American Museum, and it was through this connection that young Knight gained access to the taxidermy and paleontology workshops. The new head of the museum’s paleontology department, Henry Fairfield Osborn, immediately recognized his talents, and by 1896 was commissioning him to do nearly all the painting and restorations of prehistoric beasts that their expeditions had discovered. Although heavily committed to work for the American Museum for more than 40 years, he refused Osborn’s entreaties to join its staff, and stubbornly kept his independence. Knight continued to do a wide variety of free-lance illustrations for magazines, and remarkable sculptures, paintings, and drawings of wild animals, many based on the creatures at the Bronx Zoo. Having refused a secure staff position at the American Museum, he was nearly always broke and in debt. His traditional, realistic style of painting wildlife was hard to sell in the midst of the wave of new artists from Europe (Picasso, Gauguin, Matisse, Duchamp, and others), so he rarely got commissions from wealthy patrons to keep him financially secure. He was always forgetful about money, walking away from store counters without his change, and did not know how to manage his finances. As his ties to the American Museum weakened over money issues, he eventually received commissions to do grand murals for the Field Museum in Chicago and a series of paintings for the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles. By the time these murals were commissioned, Knight was legally blind, and had to employ assistants to render his small sketches into wall-sized paintings that Knight could see only as a blur. Late in life, he always carried a piece of paper with his address, so if he became lost due to his blindness, someone could help him get home. After he had completely lost his sight, Knight’s health began to deteriorate, and he died in 1953, at the age of 79.

This Stegosaurus Arch, rendered by Knight in shades of colored cement, guards the Reptile House entrance at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo in Washington DC. © Smithsonian National Zoo, Jesse Cohen. (Click image to enlarge)

But Milner’s book is more than just a biography of a pioneering paleoartist. It is gloriously illustrated with Knight’s art, rendered in full color on quality paper stock by Abrams, a noted publisher of art books, so the colors just pop out of the page. (Milner is credited as the art editor of the book as well as the author.) Many of the sketches were previously unpublished, and show the artist’s early ideas for works that later become iconic. Others are truly remarkable, such as the guest book pages from Henry Fairfield Osborn’s mansion, signed by J.P. Morgan and other powerful people—with prehistoric animal doodles by Knight. Milner’s book has chapters on the Bronx Zoo and Knight’s connection with its early history, including his amazing sculptures for its elephant house; on how Knight’s art helped to save the bison from extinction; Knight’s sketches showing animals dissected down to their muscles, which helped make Knight’s creations more realistic and life-like; pages and pages of gorgeous paintings of the great cats and exotic birds; descriptions of how Knight prepared sketches and anatomical drawings before he painted, and how he fleshed out mounted skeletons of extinct beasts into amazing miniature sculptures; his role in creating Sinclair Oil’s “Dinoland” for the 1964 New York World’s Fair; and his trip to Europe to study early Paleolithic cave paintings and connect with the Ice Age artists who made them. The book also includes an Introduction by Knight’s granddaughter, Rhoda Knight Kalt, with her charming childhood recollections of her grandfather.

Recently restored Field Museum mural depicting the iconic confrontation between a Triceratops and a T. rex. Knight’s famous dinosaurian faceoff has been copied in countless movies, toys, and comic books. © Field Museum. (Click image to enlarge)

Inevitably in a project as large and complex as this, a few small errors creep in—mostly the spelling of one or two scientific names in captions (such as Protoceras and Megaceros on p. 66). However, Milner was conscientious in making sure that the captions reflect the most current scientific names and interpretations of these extinct creatures. More importantly, the high-quality reproduction of the art and the many previously unpublished sketches and doodles give us an unprecedented insight into Knight’s artistic techniques and his love of his animal subjects. Milner shows how Knight’s conception of prehistoric animals changed over time as the scientific ideas changed, so he rendered the great sauropods as both sluggish tail-dragging lizard-like creatures in swamps (the view a century ago) and also as animals of the dry land with necks and tails held out straight (the modern view). He rendered a famous painting inspired by the insights of the ailing Edward Drinker Cope that showed the modern conception of the predatory Allosaurus (then called Laelaps) jumping on another in a very active pose, a view which has come back into scientific favor a century later. At Osborn’s urging, Knight had spent weeks absorbing Cope’s expertise shortly before the pioneering paleontologist died in 1897.

An African elephant head, one of a pair of Knight sculptures that flank the portal of the Bronz Zoo’s Elephant House, completed in 1906. Photo by Viktor Deak. © Richard Milner.

(Click image to enlarge)

In 1934, Osborn wrote, “Charles R. Knight is the greatest genius in the line of prehistoric restoration that the science of paleontology has ever known. His work in the American Museum will endure for all time.” Stephen Jay Gould pointed out that although Knight never published a single scholarly work in paleontology, he was more influential in shaping our ideas about the prehistoric world than any scientist. More to the point, Knight is the source of nearly all modern paleoart, revered by all modern dinosaur artists and Hollywood dinosaur animators as their founding father. Even though he was nearly blind, without his visualization of prehistoric creatures our modern obsession with dinosaurs might never have occurred, or followed the path that it did. The world of extinct animals that seems so familiar to us is largely Knight’s vision, and we can be thankful for his amazing skills, passion, and dedication in making the prehistoric past come alive.

About the Author of this Review

DR. DONALD R. PROTHERO was Professor of Geology at Occidental College in Los Angeles, and Lecturer in Geobiology at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. He earned M.A., M.Phil., and Ph.D. degrees in geological sciences from Columbia University in 1982, and a B.A. in geology and biology (highest honors, Phi Beta Kappa) from the University of California, Riverside. He is currently the author, co-author, editor, or co-editor of 32 books and over 250 scientific papers, including five leading geology textbooks and five trade books as well as edited symposium volumes and other technical works. He is on the editorial board of Skeptic magazine, and in the past has served as an associate or technical editor for Geology, Paleobiology and Journal of Paleontology. He is a Fellow of the Geological Society of America, the Paleontological Society, and the Linnaean Society of London, and has also received fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Science Foundation. He has served as the President and Vice President of the Pacific Section of SEPM (Society of Sedimentary Geology), and five years as the Program Chair for the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology. In 1991, he received the Schuchert Award of the Paleontological Society for the outstanding paleontologist under the age of 40. He has also been featured on several television documentaries, including episodes of Paleoworld (BBC), Prehistoric Monsters Revealed (History Channel), Entelodon and Hyaenodon (National Geographic Channel) and Walking with Prehistoric Beasts (BBC). His website is: www.donaldprothero.com. Check out Donald Prothero’s page at Shop Skeptic.

Be Among the First to Hear About

Skeptics Society Geology Tours!

Led by paleontologist/geologist Dr. Donald R. Prothero, our often multi-day excursions tour some of the best geologic wonders in the United States. Visit some of the richest dinosaur-bearing deposits in the world, and collect amazing trilobites. Decipher the geologic story behind the amazing scenery at Zion, Bryce, and Capitol Reef National Parks, Death Valley, Kelso Dunes, the Great Basin, Redrock Canyon and more. Read about our past geology tours and sign up for advance notification about our next tour!

NEW ON MICHAELSHERMER.COM

Another Fatal Conceit

In this review of The Darwin Economy: Liberty, Competition, and the Common Good by Robert H. Frank, Michael Shermer discusses a lesson from evolutionary economics regarding bottom-up self-organization rather than top-down government design. This review appeared online in the Journal of Bioeconomics in March 2012.

NEW ON HUFFINGTONPOST.COM

Debate: Are Science and Religion Incompatible?

Do you believe in God? Or do you put your faith in science? Kenneth Miller faces off against Michael Shermer at HuffingtonPost.com in this hot-button debate about the compatibility of science and religion. Vote on the debate in the pre-debate poll and then afterward again to see who changed the most minds!

SKEPTICALITY EPISODE 178

You Are Not So Smart

This week on Skepticality, Derek has a discussion with David McRainy about his latest book, You Are Not So Smart. McRainy is a journalist who mainly covers subject matter in the areas of psychology and technology, which lead him to researching many of the claims to which skeptics gravitate. In this interview, you’ll find out why you probably have too many friends on Facebook, why your memory is mostly fiction, and other ways in which you are probably deluding yourself.

Lecture this Monday at Caltech

Revelations: Visions, Prophecy, and Politics in the Book of Revelation

with Dr. Elaine Pagels

Monday, March 19, 2012 at 7:30 pm

Baxter Lecture Hall

A STARTLING EXPLORATION of the history of the most controversial book of the Bible, the religious scholar Elaine Pagels tackles The Book of Revelation, the surreal apocalyptic vision of the end of the world…or is it? Pagels returns The Book of Revelation to its historical origin, written as its author John of Patmos took aim at the Roman Empire after what is now known as “the Jewish War,” in 66 CE. Militant Jews in Jerusalem, fired with religious fervor, waged an all-out war against Rome’s occupation of Judea and their defeat resulted in the desecration of Jerusalem and its Great Temple. Pagels persuasively interprets Revelation as a scathing attack on the decadence of Rome. Soon after, however, a new sect known as “Christians” seized on John’s text as a weapon against heresy and infidels of all kinds—Jews, even Christians who dissented from their increasingly rigid doctrines and hierarchies. In a time when global religious violence surges, Revelations explores how often those in power throughout history have sought to force “God’s enemies” to submit or be killed.

Tickets are first come, first served at the door. Seating is limited. $8 for Skeptics Society members and the JPL/Caltech community, $10 for nonmembers. Your admission fee is a donation that pays for our lecture expenses.

Followed by Two Events on the Same Day

for the Price of One!

Sunday, March 25, 2012 at 2 pm

A Great Debate: “Has Science Refuted Religion?”

with Sean Carroll & Michael Shermer v. Dinesh D’Souza & Ian Hutchinson

Sam Harris on Free Will

This lecture will begin after the debate ends.

This Debate/Harris lecture is now SOLD OUT.

TICKETS: $10 Skeptics Society members/Caltech/JPL community; $15 everyone else. Tickets may be purchased in advance through the Caltech ticket office at 626-395-4652 or at the door. Ordering tickets ahead of time is strongly recommended. The Caltech ticket office asks that you do not leave a message. Instead call between 12:00 and 5:00 Monday through Friday.

The Creative Destruction of Medicine: How the

Digital Revolution Will Create Better Health Care

Digital Revolution Will Create Better Health Care

WHAT HAPPENS WHEN YOU COMBINE cellular phone technology with the cellular aberrations in disease? Or create a bridge between the digital revolution with the medical revolution? How will minute biological sensors alter the way we treat lethal illnesses, such as heart attacks or cancer? These questions, and more, are answered by Dr. Eric Topol, a leading cardiologist, gene hunter and medical thinker. Topol’s analysis draws us to the very frontlines of medicine and leaves us with a view of a landscape that is both foreign and daunting. As baby-boomers approach retirement age, they are going to be confronted with important choices among many new medical technologies. Don’t miss this important lecture based on Dr. Topol’s new book.

TAGS: Eric Topol, medical revolution, medical technologies, medicine12-03-07

In this week’s eSkeptic:

NEW ON MICHAELSHERMER.COM

Opting Out of Overoptimism

In Michael Shermer’s March “Skeptic” column for Scientific American, he discusses what psychologist Daniel Kahneman calls the “pervasive optimistic bias.” Optimism can slide dangerously into overoptimism when we willfully distort reality to extremes.

Hell Hath No Furry!

Episode 50 of MonsterTalk takes us to a small English village in the 1570s where a morning church service is interrupted by a horrific storm which heralds, perhaps, the appearance of Satan himself in the form of a huge black hound. Join us as we talk with David Waldron (author of Shock! The Black Dog of Bungay) as he helps us discover the facts behind this creepy tale—a tale which influences paranormal literature even today.

The Latest Episode of Mr. Deity: Mr. Deity and The Artist

WATCH THIS EPISODE | DONATE | NEWSLETTER | FACEBOOK | MrDeity.com

About this week’s eSkeptic

Despite the best efforts of skeptics and teachers to advance scientific thinking, paranormal beliefs and pseudoscientific thinking continue to be commonplace. It is a common popular stereotype that knowledge of science and belief in the paranormal are like opposite ends of a teeter totter: with one tending to rise as the other falls. However, the landscape of belief is considerably more complicated than that. Science education may not be enough when we lack the ability to critically evaluate the evidence for claims. In this week’s eSkeptic, we present an article from Skeptic 9.3 that examined the relationship between science knowledge and paranormal beliefs.

The above illustration is copyright © 2002 Daniel Loxton.

Science Education is

No Guarantee of Skepticism

by Richard Walker, Steven J. Hoekstra,

and Rodnet J. Vogl

Many skeptics take a measured amount of pleasure in the kinds of tasks often set before them: evaluating blurry photographs, conducting laboratory experiments that reduce or eliminate trickery, critiquing flawed science and pseudoscience, and countering the claims of obvious charlatans. Of course, skeptics hope that their efforts aid in advancing science education.1 In spite of these efforts, survey data from several sources suggests that paranormal belief and pseudoscientific thinking continue to be commonplace.2

Skeptics often use these findings to reinforce arguments for more science education. Their argument is based upon the largely untested assumption that increased science knowledge reduces the number of paranormal beliefs an individual holds. However, this assumption may not be valid. Andrew Ede recently argued that science education may do little to raise the level of rational thinking and may, in fact, actually deter it!3 Recent debates about including creation science and/or eliminating evolution from high school biology curricula4 are a case in point indicating that many policy makers, members of the public, and a few educators are confused about how to critique and compare theories in order to separate facts from beliefs. Ede identified three reasons why this may be true:5

- Science classes, broadly defined, primarily teach technical skills rather than emphasizing critical thinking. Labs are conducted in which there is a “right answer” that the instructor knows, and it is up to the student to manipulate the project until the “right answer” is realized.

- Science classes typically review research findings without placing the research in the proper context. This can lead to incorrect assumptions or overgeneralizations.

- Science implicitly emphasizes its elite status over other points of view. Therefore, data and graphs are accepted uncritically because they are based on “scientific,” “clinical,” or “laboratory” studies. A lab coat guarantees an aura of expertise.

The overall result is that teaching scientific “facts” is emphasized, while individuals are not given the skills with which to critically evaluate the claims that are presented to them. People are placed in the position of accepting or rejecting claims based on what they are told to believe, rather than being able to critically evaluate the evidence.6

It is possible for a student to accumulate a fairly sizable science knowledge base without learning how to properly distinguish between reputable science and pseudoscience.

A quick inspection of introductory college textbooks supports Ede’s basic arguments. As an example, most introductory psychology texts are now in excess of 500 pages, yet fewer than 15 pages are typically spent on research issues. Little or no discussion is given to the importance of evidence or how scientific methods can be used to weigh evidence. Instead, the primary emphasis of many texts is to enumerate as many scientific findings as possible. Since it is reasonable to suspect that many instructors follow the basic format of the text that has been selected for class, it is likely that class lectures spend more time on specific research findings than on the more abstract topics of empiricism and skepticism. Hence, it is possible for a student to accumulate a fairly sizable science knowledge base without learning how to properly distinguish between reputable science and pseudoscience. Fortunately, there is recently a stronger push in introductory psychology texts to correct this oversight, most strikingly by Carole Wade and Carol Tavris,7 but it still remains the exception to the rule.

Assessing Science Knowledge and Pseudoscientific Beliefs

The primary goal of this paper is to examine the relationship between science knowledge and paranormal beliefs. We reasoned that if Ede’s argument is true, then a person’s scientific knowledge base should be unrelated to pseudoscientific beliefs. If, on the other hand, science leads to skepticism about pseudoscience, science knowledge and paranormal beliefs should be inversely related.

We tested this relationship using survey methodology at three small undergraduate universities (Christian Brothers University, Kansas Wesleyan University, and Winston-Salem State University). Across our samples, a total of 207 students were surveyed (66 at CBU, 70 at KWU, and 71 at WSSU). While the precise wording of the questions varied somewhat across institutions, each survey contained two essential units, administered in counterbalanced order.

In one unit, students were given one or more measures of science knowledge. Efforts were made to select scales from nationally recognized tests and to include questions from many areas of science, including biology, chemistry, geology, and astronomy. At CBU and WSSU, we used randomly sampled science questions from practice test banks for the Praxis Series National Teacher’s Exam. At KWU, we used items selected from the General Social Survey and a self-constructed measure of science values.8 At least two test versions were used at each university (WSSU used four separate test versions). Sample questions from the Praxis Series National Teacher’s Exam9 included:

- Which of the following is the dominant source of all or nearly all of the Earth’s energy? (A) Plants, (B) Animals, (C) Coal, (D) Oil, (E) The Sun

- Which of the following is true? (A) Energy may be converted from one form to another, (B) Energy may not be converted from one form to another, (C) The energy that a moving object possesses because of its motion is correctly known as potential energy, (D) Objects which possess energy because of their position are said to have kinetic energy, (E) Most scientists readily agree that energy from nuclear fission will be the chief source of energy by the year 2005.

- Which of the following situations might cause harm to an embryo? (A) The father is RH-positive; the mother, RH-negative, (B) The mother had German measles during the first trimester of pregnancy, (C) The father is RH-negative; the mother, RH-positive, (D) A and B only, (E) B and C only.

- Heavy infections of Trichinella in people may cause a disease called trichinosis; such a situation may best be described as which of the following? (A) Parasitism, (B) Mutualism, (C) Commercialism, (D) Benevolent, (E) Benign.

- Which of the following is the main difference between an organic and an inorganic compound? (A) The former is a living compound, while the latter is a nonliving compound, (B) There are many more of the latter than of the former, (C) The latter can be synthesized only by living organisms, (D) The latter can be synthesized only by nonliving organisms, (E) The former are those that contain carbon.

- On the periodic table the symbol Pb represents which of the following? (A) Iron, (B) Phosphorus, (C) Lead, (D) Plutonium, (E) Potassium.

- Which of the metric terms is closest to the measurement of a new piece of chalk? (A) Meter, (B) Liter, (C) Gram, (D) Decimeter, (E) Kilometer.

- Which of the following is a genetic disorder? (A) Down’s Syndrome, (B) Syphilis, (C) Malaria, (D) Leukemia, (E) Emphysema.

- A litmus test conducted on HCl would have which of the following results? (A) There is no effect on the color of the litmus paper, (B) The litmus paper disintegrates, (C) The litmus paper turns blue, (D) The litmus paper turns red, (E) The carbonation causes oxygen.

- When is the Earth closest to the Sun? (A) During the summer, (B) During the fall, (C) During the winter, (D) During the spring, (E) During the spring and summer.

For each sample, we correlated the participant’s test score with their average [paranormal] belief score. Across all three samples, there was no relationship between the level of science knowledge and skepticism regarding paranormal claims.

In a second unit, students were asked to rate how much they believed in various paranormal and pseudoscientific claims. Again, efforts were made to select a cross-section of pseudoscientific claims. As skeptics, we found writing unbiased items to be a fairly difficult task, but the scale presented below, used in various forms at KWU, CBU, and WSSU, had acceptable reliability.10 Questions included:

Please rate how much you believe the following statements. Use the 7-point scale provided.

1=I do not believe in this at all; 2=I doubt very much that this is real; 3=I doubt that this is real; 4=I am unsure if this is real or not; 5=I believe this may be real; 6=I believe this is real; 7=I strongly believe this is real

- A person’s personality can be easily predicted by their handwriting.

- A person can use their mind to see the future or read other people’s thoughts.

- A person’s astrological sign can predict a person’s personality and their future.

- An ape-like mammal, sometimes called Bigfoot, roams the forests of America.

- The body can be healed by placing magnets on to the skin near injured areas.

- Healing can be promoted by placing a wax candle in your ear and lighting it.

- A dinosaur, sometimes called the Loch Ness Monster, lives in a Scottish lake.

- Sending chain letters can bring you good luck.

- The government is hiding evidence of alien visitors at places such as Area 51.

- Voodoo curses are real and have been known to kill people.

- A broken mirror can bring you bad luck for many years.

- Houses can be haunted by the spirits of people who have died in tragic ways.

- Water can be accurately detected by people using “Y”-shaped tree branches.

- Animals, such as cats and dogs, are sensitive to the presence of ghosts.

Science Test Scores

After scoring this portion of the survey, we used the total number of correct responses as data for each participant. While the scores did show a fair degree of variability, the averages were generally near the midpoint (CBU M=7.42, SD=2.27, out of a possible 15; KWU M=3.52, SD=.33, on a 1 to 5 scale; WSSU M=5.8, SD = 1.96, out of a possible 10).11

Paranormal / Pseudoscientific Beliefs

Unlike previous studies that have examined specific beliefs (e.g., UFOs, ESP), we were interested in these beliefs as a whole. We wanted a single representative score for each participant. We calculated the average belief score for each participant, with higher ratings indicating greater overall belief. When looking at these scores, remember that the rating ranged from “No belief” to “Total belief.” Looking across the three samples, the average belief rating was at or below the midpoint of the scale (CBU M=1.96, SD=.76, on a 7- point scale; KWU M=2.52, SD=.58, on a 5-point scale; WSSU M=2.9, SD=.91, on a 7-point scale), although there were individuals ranging from complete skeptics to complete believers.

Science Test Scores and Paranormal / Pseudoscientific Beliefs

We were interested in whether science test scores were correlated with paranormal beliefs. For each sample, we correlated the participant’s test score with their average belief score. Across all three samples, the correlation between test scores and beliefs was non-significant (CBU r(65)=-.136, p>.05; KWU r(69)=.107, p>.05; WSSU r(70)=.031, p>.05). In other words, there was no relationship between the level of science knowledge and skepticism regarding paranormal claims.

Wanted: A Good Baloney Detector!

These results are consistent with the notion that having a strong scientific knowledge base is not enough to insulate a person against irrational beliefs. Students who scored well on these tests were no more or less skeptical of pseudoscientific claims than students who scored very poorly. Apparently, the students were not able to apply their scientific knowledge to evaluate these pseudoscientific claims. We suggest that this inability stems in part from the way that science is traditionally presented to students: Students are taught what to think but not how to think.

These results need to be replicated using different materials and participants, although the diversity of measures and samples presented here suggests that there is some validity to our conclusions. While some might contend that our tests did not fully measure science knowledge, we counter this concern by emphasizing that our test questions were drawn from national tests designed to assess scientific reasoning. Thus, if there is a bias in our procedure, this bias is entrenched in science education. In our view, addressing the following questions can serve to clarify the relation between science education and pseudoscientific thinking.

First, do pseudoscientific beliefs vary by academic major? If science does discourage such beliefs, then one might suspect that science majors should view these beliefs more skeptically than perhaps religion or art majors. While there is evidence that scientists are more skeptical of claims than other individuals, it is unclear whether this skepticism is readily transferred to undergraduate science majors. After all, strange beliefs seem to be found among students of many disciplines. Unfortunately, our access to samples was too small to adequately test differences between majors.

Second, do pseudoscientific beliefs vary by education level? As students advance through college and gain experience and critical thinking skills, one might expect pseudoscientific beliefs to decrease. Although our data did not address this issue, other studies on skepticism suggest that an individual’s education level may not ward off such beliefs.12

Finally, can academic courses or programs that systematically raise or lower belief in pseudoscience be identified? It is possible that particular courses may encourage or discourage pseudoscientific beliefs. These courses need to be identified, and in the case of the latter, the key elements of these courses need to be disseminated to other science instructors. This is especially important when classroom information can support or contradict information from other sources, such as mass media. Our results suggest that we should not be overly optimistic, but more systematic investigations are needed.

Baloney Detection Kit

by Michael Shermer and Pat Linse

This 16-page booklet is designed to hone your critical thinking skills. It includes suggestions on what questions to ask, what traps to avoid, specific examples of how the scientific method is used to test pseudoscience and paranormal claims, and a how-to guide for developing a class in critical thinking.

ORDER the 16-page booklet

We hope that our findings force fellow skeptics to rethink some of their assumptions. Science education, in its current form, seems to do little to offset pseudoscientific beliefs, and may in fact give students reason to accept science fiction as science fact. As skeptics and teachers, we need to do more than merely debunk extraordinary claims. While these demonstrations are informative and entertaining, they need to be coupled with thoughtful discussions of scientific reasoning. Carl Sagan suggested that good scientific reasoning demands the same type of skepticism that is needed to buy a good used car. In short, he said that students of science need a good baloney detector.13 We agree. The Skeptics Society’s recent publication of the Baloney Detection Kit that instructs teachers on how to teach just such a course is a step in the right direction.14 Provisional scientific truth must be separated clearly from myth. We urge skeptics to help students gain the necessary skills to make such distinctions both inside and outside the classroom.![]()

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: We would like to thank the undergraduate research assistants who helped collect and tabulate the data on this research project: Reggie Andrews, Paul Delph, Stefanie McGee, and Lakisha Pinson. Correspondence concerning this article should be directed to W. Richard Walker, Department of Social Sciences, Winston-Salem State University, Winston-Salem, NC 27110

References

- Sagan, C. 1996. The Demon Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark. New York: Ballantine; Shermer, M. 1997. Why People Believe Weird Things. New York: W. H. Freeman.

- Gallup, G. H., Jr., and F. Newport. 1991. “Belief in Paranormal Phenomena Among Adult Americans.” Skeptical Inquirer, 15, 137–147; Jaroff, L. 1995. “Weird Science.” Time, 145 May 15, 20, 75–76; McCarthy, P. 1987. “Pseudoteachers.” Omni, July, 74; Sparks, G. G., C. L. Nelson, and R. G. Campbell. 1997. “The Relationship Between Exposure to Televised Messages About Paranormal Phenomena and Paranormal Beliefs.” Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 41, 345–358; Zane, J. P. 1994. “Soothsayers as Business Advisors.” The New York Times, Section 4, September 11, 2.

- Ede, A. 2000. “Has Science Education Become an Enemy of Scientific Rationality?” Skeptical Inquirer, 24, 48–51.

- Milburn, J. 2001. “Board Approves New Science Standards With Renewed Emphasis on Evolution. The Salina Journal, February 15, A1.

- Ede, 2000.

- Sparks, G. G., M. Pellechia, and C. Irvine. 1998. “Does Television News About UFOs Affect Viewers’ UFO Beliefs?: An Experimental Investigation.” Communication Quarterly, 46, 284–294.

- Wade, C., and C. Tavris. 2000. Psychology (6th Ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Ankney, R. N. 2000. “Media Reliance and Science Knowledge: Do People Learn Science Information From the Media the Same Way They Learn Political Information?” Poster presented at the annual convention of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, Phoenix, AZ, August.

- Answers to the Praxis Seies National Teacher’s Exam: 1-E; 2-A; 3-D; 4-A; 5-E; 6-C; 7-D; 8-A; 9-D; 10-C.

- Reliability scores were as follows: CBU Cronbach’s alpha = 0.82; KWU Cronbach’s alpha = 0.83; WSSU Cronbach’s alpha = 0.82.

- M = Mean, or average score; SD = Standard Deviation, or the average amount of variation around the mean.

- Levitt, N. 1998. “Why Professors Believe Weird Things.” Skeptic, 6:3 28–35; Siano, B. 1999. “Public Relations: Blue Smoke, Mirrors, and Designer Science.Skeptic, 7:1, 45–55.

- Sagan, 1996.

- Shermer, M. and P. Linse. 2001. The Baloney Detection Kit. Altadena, CA: Millennium Press.

Skeptical perspectives on pseudoscientific beliefs…

-

Why People Believe Weird Things: Pseudoscience, Superstition, and Other Confusions of Our Time

Why People Believe Weird Things: Pseudoscience, Superstition, and Other Confusions of Our Time

by Michael Shermer

-

The Demon-Haunted World:

The Demon-Haunted World:

Science as a Candle in the Dark

by Carl Sagan

Watch The Baloney Detection Kit Video on YouTube

OUR ANNUAL FUNDRAISING DRIVE IS ON NOW

Help Send Skepticism 101 into the World!

- Click here to read our new plan to take Skepticism to the next level!

- Click here to make a donation now via our online store.

Monthly Recurring Donation Options Now Available

We encourage you to choose the monthly recurring donation option. Simply tell us how long you want your donation to recur (using the drop-down menu on the donation page) and we’ll set up automatic withdrawal for the amount you select.

Just for considering a donation, check out our free PDF download

created by Junior Skeptic Editor Daniel Loxton.

Lecture this Sunday at Caltech

The Creative Destruction of Medicine: How the Digital Revolution Will Create Better Health Care

with Dr. Eric Topol

Sunday, March 11, 2012 at 2 pm

Baxter Lecture Hall

WHAT HAPPENS WHEN YOU COMBINE cellular phone technology with the cellular aberrations in disease? Or create a bridge between the digital revolution with the medical revolution? How will minute biological sensors alter the way we treat lethal illnesses, such as heart attacks or cancer? These questions, and more, are answered by Dr. Eric Topol, a leading cardiologist, gene hunter and medical thinker. Topol’s analysis draws us to the very frontlines of medicine and leaves us with a view of a landscape that is both foreign and daunting. As baby-boomers approach retirement age, they are going to be confronted with important choices among many new medical technologies. Don’t miss this important lecture based on Dr. Topol’s new book.

Tickets are first come, first served at the door. Seating is limited. $8 for Skeptics Society members and the JPL/Caltech community, $10 for nonmembers. Your admission fee is a donation that pays for our lecture expenses.

Followed by…

- Revelations: Visions, Prophecy, and Politics in the Book of Revelation

with Dr. Elaine Pagels

Monday, March 19, 2012 at 7:30 pm

12-02-29

In this week’s eSkeptic:

NEW ON SKEPTICBLOG.ORG

Teaching Allah and Xenu in Indiana

Michael Shermer criticizes the Indiana State Senate’s approval last month of a bill that would allow public school science teachers to teach religious origin stories in their classrooms, including those from: Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Scientology.

Interview with David DiSalvo

SKEPTICALITY EPISODE 177

This week on Skepticality, Derek talks with David DiSalvo about his newest book, What Makes Your Brain Happy and Why You Should Do the Opposite, which delves into the ways in which we can recognize our brains’ faults and use them to live more fulfilled lives. DiSalvo is an award-winning public outreach and education specialist, and a popular writer for Scientific American Mind, Psychology Today, and other publications and blogs.

About this week’s eSkeptic

Rapidly advancing technologies may have the potential not only to spread information but to solve some of humanity’s most vexing problems. In this week’s eSkeptic, Michael Shermer reviews a just-released book called Abundance: The Future is Better Than You Think by Peter H. Diamandis and Steven Kotler (Free Press, ISBN: 978-14516-1421-3). Together they have produced a manifesto for the future that is grounded in practical day-to-day solutions addressing the world’s most pressing problems: overpopulation, food, water, energy, education, healthcare, and freedom. A slightly different version of this review was originally published in the Wall Street Journal on Wednesday, February 22.

It’s Getting Better All the Time

a review by Michael Shermer

If you read a major newspaper such as the New York Times or Wall Street Journal cover to cover every day for a week you will have consumed more digital information than a citizen in the 17th century Western world would have encountered in a lifetime. That’s a lot of digital data, but it’s nothing compared to what is on the immediate horizon. By comparison, from the earliest stirrings of civilization thousands of years ago to the year 2003, all of humankind created a grand total of five exabytes of digital information. An exabyte is one quintillion bytes, or one billion gigabytes. That’s a one followed by 18 zeros, and from 2003 through 2010 we created five exabytes of digital information every two days. By 2013 we will be producing five exabytes every ten minutes. How much information is this? The 2010 total of 912 exabytes is the equivalent of 18 times the amount of information contained in all the books ever written. This means that the world is not just changing, and the change is not just accelerating, but the rate of the acceleration of change is itself accelerating.

This and many other examples of accelerating returns are documented in Abundance: The Future is Better Than You Think by Peter H. Diamandis and Steven Kotler. Diamandis is the Chairman and CEO of the X PRIZE Foundation and the founder of more than a dozen high tech companies. Kotler is a journalist who writes for the New York Times magazine, Wired, Discover, GQ, and National Geographic. Together they have produced a manifesto for the future that is grounded in practical day-to-day solutions addressing the world’s most pressing problems: overpopulation, food, water, energy, education, healthcare, and freedom. They suggest that “humanity is now entering a period of radical transformation where technology has the potential to significantly raise the basic standard of living for every man, woman and child on the planet. Within a generation, we will be able to provide goods and services that were once reserved for the wealthy few to any and all who need them.” Accelerating change is happening in many areas:

- Information: A Masai warrior with a smartphone on Google has access to more information than the President of the United States did just 15 years ago.

- Technology: Today more people have access to a cell phone than a toilet.

- Computing: In 15 years, the average $1000 laptop should be computing at the rate of the human brain.

- Education: The Khan Academy’s YouTube tutorial videos on over 2200 topics from Algebra to Zoology draw over two million viewings a month.

- Medicine: The field of personalized medicine—an industry that didn’t exist before 2003—is now growing at 15 percent a year and will reach $452 billion by 2015.

- Aging: The centenarian population is doubling every decade, from 455,000 in 2009 to over 4.1 million by 2050.

- Poverty: The number of people living in absolute poverty has fallen since the 1950s and has dropped by more than half. At the current rate of decline it will reach zero by around 2035.

- Expenses: Groceries today cost 13 times less than 150 years ago in inflation adjusted dollars.

- Business: Billion dollar companies are being created faster than ever—YouTube grew from startup to $1.6 billion in 18 months; Groupon went from startup to $6 billion in two years.

- Standard of living: 95 percent of Americans now living below the poverty line have electricity, Internet, water, flushing toilets, a refrigerator and a television. John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie, among the richest people on the planet, enjoyed few of these luxuries.

The timing of this book is propitious. Between the 2011 Christian end-times soothsayers, the 2012 Mayan Calendar doomsayers, gloomy environmentalists, and the announcement in January by the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists that their Doomsday clock had been advanced to five minutes to midnight (and now includes environmental degradation and biological weapons alongside nuclear weapons as the likeliest candidates for our demise), how can anyone be so optimistic? With seven billion people now pressing up against the Earth’s carrying capacity there are seemingly intractable problems to be solved. Isn’t pessimism the appropriate response? Who’s right, the optimists or the pessimists?

The problem turns on cognitive biases that slant our interpretation of the data. Optimism is good for overcoming obstacles that are part of daily life, but over-optimism can blind one to adversities that should be heeded. In a Canadian study of inventors, for example, of those who participated in the Inventor’s Assistance Program in which they paid for objective evaluations of their invention on 37 different criteria, 47 percent continued working on their projects even after they were told that it was hopeless, and as a consequence they incurred losses double that of their more realistic colleagues. Optimism helps entrepreneurs override normal “loss aversion,” in which losses hurt twice as much as gains feel good, an emotion we evolved in our evolutionary environment of scarcity and uncertainty. Loss aversion leads most of us to be short term in our thinking. We discount the future in ways so predictable that economists have formulas to describe it. We focus on immediate events and bad news, and are blind to long-term trends and good news. Diamandis and Kolter not only acknowledge these cognitive biases, they address them head on as one more obstacle to abundance to be overcome.

I have long been skeptical of both doomsayers who project the end of the world in our generation, as well as futurists who proclaim that the Next Big Thing to revolutionize humanity and save the planet will happen in our lifetime. To date, the end-of-the world doomsters have been spectacularly and often embarrassingly wrong. And the futurists who craft a utopian narrative about how one day we will live forever, colonize the galaxy in starships, and materialize food and drink in replicators are indistinguishable from producers of science fiction and fantasy. Skeptics are from Missouri: Show Me. Diamandis and Kolter do just that, describing in specific detail how the revolution has already begun and that such abundance can be realized in our lifetime through three current forces:

- Do-It-Yourself (DIY) backyard tinkerers such as the aviation pioneer Burt Rutan, who won the X-Prize for achieving privatized space flight, and the geneticist J. Craig Venter, who beat the U.S. government in the race to sequence the human genome. Thousands of such DIYers are working away in garages and warehouses innovating solutions in neuroscience, biology, genetics, medicine, agriculture, robotics, and numerous other areas.

- Techno-philanthropists such as Bill Gates (malaria), Mark Zuckerberg (education), Pierre and Pam Omidyar (electricity in the developing world), and many more are dedicating significant portions of their vast fortunes to solving specific problems.

- The bottom billion, the poorest of the poor who have nowhere to go but up, as they become plugged into the global economy through micro-financing and the Internet will lift all boats with them as they work toward having clean water, nutritious food, affordable housing, personalized education, top-tier medical care, and ubiquitous energy. Don’t think of seven billion people as too many mouths to feed; think of them as seven billion brains who can think about solving heretofore insoluble problems.

The principles behind this process of abundance creation include: bottom-up v. top-down; non-linear v. linear; horizontal v. hierarchical; private entrepreneurship v. public works; small group v. large corporation; competition for prizes v. make-work for paycheck; risk disposed v. risk averse; Nonzero win-win v. zero-sum win-lose. The trend lines outlined by the authors are real enough, and if these principles were applied worldwide such abundance should indeed be realizable, in the long run if not in the short. The biggest hurdles, however, are not scientific or technological, but political. There are still too many corrupt dictators, third-world thugs, dear leaders, and backwards looking governments that would prefer corralling their people into medieval theocracies in order to enrich themselves. Still, as Matt Ridley demonstrated in The Rational Optimist and Steven Pinker in The Better Angels of Our Nature, even the political trend lines are moving in the right direction. In any case, as Diamandis likes to say: “The best way to predict the future is to create it yourself.”

Skeptical perspectives on the future…

-

The Rational Optimist:

The Rational Optimist:

How Prosperity Evolves

with Dr. Matt Ridley

-

The World in 2050: Four Forces Shaping Civilization’s Northern Future

The World in 2050: Four Forces Shaping Civilization’s Northern Future

with Laurence Smith

-

The Future of Science, Technology,

The Future of Science, Technology,

and Education

with Bill Nye and James Randi

Our Next Lecture: Dr. Eric Topol

The Creative Destruction of Medicine: How the Digital Revolution Will Create Better Health Care

with Dr. Eric Topol

Sunday, March 11, 2012 at 2 pm

Baxter Lecture Hall

WHAT HAPPENS WHEN YOU COMBINE cellular phone technology with the cellular aberrations in disease? Or create a bridge between the digital revolution with the medical revolution? How will minute biological sensors alter the way we treat lethal illnesses, such as heart attacks or cancer? These questions, and more, are answered by Dr. Eric Topol, a leading cardiologist, gene hunter and medical thinker. Topol’s analysis draws us to the very frontlines of medicine and leaves us with a view of a landscape that is both foreign and daunting. As baby-boomers approach retirement age, they are going to be confronted with important choices among many new medical technologies. Don’t miss this important lecture based on Dr. Topol’s new book.

Tickets are first come, first served at the door. Seating is limited. $8 for Skeptics Society members and the JPL/Caltech community, $10 for nonmembers. Your admission fee is a donation that pays for our lecture expenses.

Followed by…

- Revelations: Visions, Prophecy, and Politics in the Book of Revelation

with Dr. Elaine Pagels

Monday, March 19, 2012 at 7:30 pm

Abundance: Why the Future Will Be

Much Better Than You Think

Much Better Than You Think

SINCE THE DAWN OF HUMANITY, a privileged few have lived in stark contrast to the hardscrabble majority. Conventional wisdom says this gap cannot be closed. But it is closing—fast. According to the X-Prize creator and entrepreneur Peter H. Diamandis, we will soon be able to meet and exceed the basic needs of every man, woman and child on the planet. Abundance for all is within our grasp through four forces: exponential technologies, the DIY innovator, the Technophilanthropist, and the Rising Billion. Diamandis establishes hard targets for change and lays out a strategic roadmap for governments, industry and entrepreneurs, giving us plenty of reason for optimism.

TAGS: abundance, Peter Diamandis12-02-22

In this week’s eSkeptic:

Lecture this Sunday: Dr. Peter Diamandis

Abundance: Why the Future Will Be Much Better Than You Think

with Dr. Peter Diamandis

Baxter Lecture Hall

This lecture will take place on

Sunday, February 26, 2012 at 2 pm.

SINCE THE DAWN OF HUMANITY, a privileged few have lived in stark contrast to the hardscrabble majority. Conventional wisdom says this gap cannot be closed. But it is closing—fast. According to the X-Prize creator and entrepreneur Peter H. Diamandis, we will soon be able to meet and exceed the basic needs of every man, woman and child on the planet. Abundance for all is within our grasp through four forces: exponential technologies, the DIY innovator, the Technophilanthropist, and the Rising Billion. Diamandis establishes hard targets for change and lays out a strategic roadmap for governments, industry and entrepreneurs, giving us plenty of reason for optimism.

Tickets are first come, first served at the door. Seating is limited. $8 for Skeptics Society members and the JPL/Caltech community, $10 for nonmembers. Your admission fee is a donation that pays for our lecture expenses.

Followed by…

- The Creative Destruction of Medicine: How the

Digital Revolution Will Create Better Health Care

with Dr. Eric Topol

Sunday, March 11, 2012 at 2 pm

Jesus, the Easter Bunny, and Other Delusions:

Just Say No!

In this talk, Dr. Peter Boghossian argues that faith-based processes are unreliable and unlikely to lead one to the truth. Since our goal as knowers is to have more true beliefs than false ones, faith, as a process for getting to the truth, should be abandoned in favor of other, more reliable processes. The talk was followed by a question and answer session from the audience. This presentation, sponsored by the Freethinkers of Portland State University and published by philosophynews.com, was given by Dr. Peter Boghossian of Portland State University on January 27, 2012.

What is a Cult?

What is a cult? What is the difference between a cult and a religion? Who joins cults and why? What are the social, cultural, and psychological reasons that people join cults? In this lecture Dr. Shermer presents research from sociologists and psychologists to attempt to answer these questions, while examining several examples of cults from recent history and when and why they can be dangerous.

Evonomics: Evolutionary Economics

In this lecture Dr. Shermer considers the evolutionary origins of trade through the study of the economy as an evolving complex adaptive system grounded in a human nature that evolved functional adaptations to survival as a social primate species in the Paleolithic epoch in which we evolved. That is, the economy is a very complex system that changed and adapted to circumstances as it evolved out of a much simpler system, that we spent the first 90,000 years of our lives as hunter-gatherers living in small bands, and that this environment created a psychology not always well equipped to understand or live in the modern world.

The Mind of the Market

In this lecture Shermer addresses three aspects of evolution and economics: (1) How the market has a mind of its own—that is, how economies evolved from hunter-gathering to consumer-trading. (2) How minds operate in markets—that is, how the human brain evolved to operate in a hunter-gatherer economy but must function in a consumer-trader economy. (3) How minds and markets are moral—that is, how moral emotions evolved to enable us to cooperate and how this capacity facilitates fair and free trade.

Why Darwin Matters

Evolution, Intelligent Design, and the Battle

for Science and Religion

Evolution happened, and the theory describing it is one of the most well-founded in all of science. Then why do half of all Americans reject it? There are religious and political reasons, and in Why Darwin Matters, historian of science and bestselling author Dr. Michael Shermer diffuses these fears by examining what evolution really is, how we know it happened, and how to test it. Dr. Shermer then discusses what science is through a brief history of the evolution-creation controversy—from the Scopes’ Monkey Trial of 1925 through the creationism trials of the 1960s and 1970s, to the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case of 1987, to the Intelligent Design controversies of the 1990s and 2000s—demonstrating clearly how and why creationism and Intelligent Design theory are not science. Dr. Shermer builds a powerful case for evolution as the theory that most closely parallels the Christian model of human nature and the conservative model of free market economics. Dr. Shermer was once an evangelical Christian and a creationist, and is now one of the best-known public intellectuals defending evolutionary theory, so Why Darwin Matters provides readers with an insiders’ guide to the evolution-creation debate, in which he shows why creationism and Intelligent Design are not only bad science, they are bad theology, and why science should be embraced by people of all beliefs.

Why People Believe in God

In this lecture, arguably his most controversial subject that is based on his highly-acclaimed book, How We Believe, Dr. Shermer addresses a very old question in religion with the newest data from science, namely: why do people believe in God? As he attempts to answer the question using the best theories and data from anthropology, psychology, sociology, and evolutionary biology, Dr. Shermer also addresses the important role of religion in society, the historical roots of religion and why it arose around 5000 years ago as a co-equal partner to governments and states, the origin of myths and the importance of myth-making in human cultures, and what belief in God means for individuals and society. In his always conciliatory and friendly approach to deep and controversial subjects, Dr. Shermer nevertheless is not afraid to face head-on, and courageously confront our most meaningful questions that we all have about God, the universe, and the meaning of life.

The Science of Good & Evil

The Origins of Morality and How to be Good Without God

In The Science of Good and Evil, a lecture based on the third volume in his trilogy on the power of belief, Dr. Shermer tackles two of the deepest and most challenging problems of our age: (1) The origins of morality and (2) the foundations of ethics. Does evil exist, and if so, what is the nature of evil? Is it in our nature to be moral, immoral, or amoral? If we evolved by natural forces then what was the natural purpose of morality? If we live in a determined universe, then how can we make free moral choices? Why do bad things happen to good people? Is there justice in the world beyond the social order? If there is no outside source to validate moral principles, does anything go? Can we be good without God? In this stunning conclusion to an intellectual journey into the mind and soul of humanity, Dr. Shermer peels back the inner layers covering our core being to reveal a complexity of human motives—selfish and selfless, cooperative and competitive, virtue and vice, good and evil, moral and immoral—and how these motives came into being as a product of both our evolutionary heritage and cultural history, and how we can construct an ethical system that generates a morality that is neither dogmatically absolute nor irrationally relative, a rational morality for an age of science.

Skepticism 101: How to Think Like a Scientist

Without Being a Geek

Without Being a Geek

In this introductory lecture to the study of skepticism, Dr. Shermer defines skepticism and what it means to be a skeptic, employing numerous examples from the pages of Skeptic magazine to illustrate what science is and how it works, how to think like a scientist, how to think about weird things, what constitutes an extraordinary claim and why we require extraordinary evidence for it, and how to test claims of the paranormal.

The Psychology of Political Beliefs

Taken from the chapter in his book The Believing Brain on the psychology of political beliefs, Dr. Shermer considers how belief systems operate in the realm of politics, economics, and ideologies. He reviews the research on why people vote Republican or Democrat, why we are so predictable in our political beliefs that if you know where someone stands on, say, abortion, you can predict where they stand on a number of other political issues, and what these political beliefs say about the nature of human nature.

Rise Above: How the World Works…or Should Work

In this lecture, Dr. Shermer integrates several strands of thought on the evolution of morality, ethics, the history of civilization, and how to be good without god by creating a society that accentuates the positive aspects of human nature while attenuating the negative aspects. He shows how and why both liberal democracy and free trade lead to better societies and that we can “rise above” our inner demons by bringing out the better angels of our nature.

Shermer’s Last Law

Any Sufficiently Advanced Extraterrestrial Intelligence is Indistinguishable from God

In this brief lecture, Dr. Shermer demonstrates why the Intelligent Design creationists’ and theologians’ search for a designer god can only result in the discovery of an extraterrestrial intelligence; one with such power that it can create life, planets, stars, and even universes. As Dr. Shermer states, “Any sufficiently advanced extraterrestrial intelligence is indistinguishable from God.” In this lecture Dr. Shermer also discusses the potential trajectory of our own technological advancements.

12-02-15

DATE CORRECTION NOTICE: Dr. Peter Diamandis’ lecture will take place on Sunday, February 26, 2012 at 2 pm. It was incorrectly stated as Saturday in last week’s eSkeptic.

In this week’s eSkeptic:

- Follow Michael Shermer: Alfred Russel Wallace and The Nature of Science

- Skepticality: Interview with Daniele Bolelli

- New Episode: Mr. Deity and The Occupation

- Feature Article: Darwin’s Legacy

- Upcoming Lecture at Caltech: Dr. Peter Diamandis

- Special Double Caltech Event: A debate, and a lecture (Sam Harris)

- Fundraising Drive on Now: Help Send Skepticism 101 into the World!

NEW ON SKEPTICBLOG.ORG

The Natural & the Supernatural:

Alfred Russel Wallace and The Nature of Science

A couple weeks ago, Michael Shermer participated in an online debate at Evolution News & Views with Center for Science & Culture fellow Michael Flannery on the question: “If he were alive today, would evolutionary theory’s co-discoverer, Alfred Russel Wallace, be an intelligent design advocate?” In this week’s Skepticblog, we present part three of the debate.

Interviews with Tom Merritt, Bob Blaskiewicz & Eve Siebert

SKEPTICALITY EPISODE 176

This week on Skepticality, Derek sits down with Tom Merritt to discuss the importance of critical thinking when assessing heated issues such as the much-reported working conditions at computer manufacturer Foxconn, a large supplier of Apple components. Then, Bob Blaskiewicz and Eve Siebert join Derek to discuss the evidence that Shakespeare was actually the man who penned the famous plays of the Globe Theater, and how the movie Anonymous is steeped in fiction.

The Latest Episode of Mr. Deity: Mr. Deity and the Occupation

WATCH THIS EPISODE | DONATE | NEWSLETTER | FACEBOOK | MrDeity.com

About this week’s eSkeptic

In this week’s eSkeptic, Donald R. Prothero remembers Charles Darwin (on the occasion of what would have been his 203rd birthday this past Sunday). Prothero reminds us that it was 40 years ago this year that the most frequently cited paper in the history of paleontology was published: none other than the legendary 1972 article by Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould which proposed the “punctuated equilibrium” hypothesis. Prothero also shares some insights from his own research.

Read Prothero’s bio after the article.

Darwin’s Legacy

by Donald R. Prothero

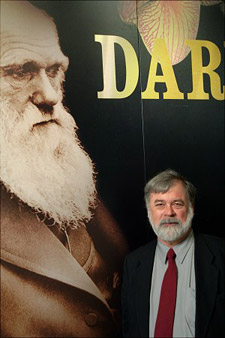

Niles Eldredge as he looks today, Curator Emeritus at the American Museum of Natural History

Last Sunday, February 12, we celebrated the 203rd birthday of two of the most important figures in world history, Abraham Lincoln—and Charles Darwin. To mark the occasion properly, I spent part of my weekend visiting the Creation Museum in Santee, California, with Carrie Poppy and Ross Blocher of the podcast “Oh no, Ross and Carrie!” (more on that trip in my March 7 Skepticblog post). But I thought I’d mark this anniversary with a discussion of another important anniversary in the history of evolutionary science.

It was 40 years ago this year that the most frequently cited paper in the history of paleontology was published. That was none other than the legendary 1972 article by Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould which proposed the “punctuated equilibrium” hypothesis. (Full disclosure: I took seminars from Niles while I was a student at the American Museum of Natural History, and Steve Gould was very interested in and supportive of my research even though I was not his student in a formal sense). At the time the paper came out, the dominant concept about speciation was the allopatric speciation model. In a nutshell, good biological evidence showed that new species arise not in the large mainland populations (with their extensive gene mixing) but in small isolated populations with unusual gene frequencies (peripheral isolates), usually living separate (allopatric) from the mainland population. Once these allopatric populations were no longer isolated but remixed with the mainland population, they would be genetically and behaviorally distinct from their parent species. Thus, they would be no longer capable of interbreeding, which is part of the definition of a biological species.

Experimental biology … may reveal what happens to a hundred rats in the course of ten years under fixed and simple conditions, but not what happened to a billion rats in the course of ten million years under the fluctuating conditions of earth history. Obviously the latter problem is more important.

Even though the allopatric speciation model was accepted by biologists as early as 1942, it took paleontologists 30 years to recognize its implications. In their historic 1972 paper, Niles and Steve pointed out that if you took Ernst Mayr’s allopatric speciation model seriously, it would predict that species should arise in a normal biological time frame: a few years to a few hundred years at most. That’s a geologic instant, the difference between one bedding plane and the next in strata that span millions of years. The allopatric speciation model also predicted that species should arise in small, peripherally isolated areas, so they were unlikely to be fossilized in the few places for which we have a good fossil record. Rather than slow gradual change through millions of years of strata (the “phyletic gradualism” model), the allopatric speciation model accepted by biologists should give a fossil record where species seem to appear suddenly without any gradual transition preserved (“punctuation”), and then persist for long periods of time without change (“equilibrium”).

(left–right) Stephen Jay Gould, Michael Shermer, and yours truly, Mt. Wilson Observatory, Pasadena,CA (2001)

The “punctuated equilibrium” paper is a masterpiece of writing and incisive thinking, which poses a number of interesting issues. The first part is a general discourse on the philosophy of science, which argues that all scientists are products of their time and culture and tend to see what they expect to see. In this context, Darwin led paleontologists to expect phyletic gradualism, which they vainly tried to document for over a century before the allopatric speciation model came along. Then Eldredge and Gould introduced the details of the allopatric model, described punctuated equilibrium, and give examples from their own research (phacopid trilobites from Eldredge, Bahamian land snails from Gould). Every time I teach a paleontology class, I always assign the original paper as required reading, and then lead a class discussion section teasing it apart. Like fine wine, the paper gets better every time I reread it. I’m always amazed at what insights it contains, what future debates it triggered or foreshadowed, and how different students pick up different elements when they read it for the first time.

For the first decade after the paper was published, it was the most controversial and hotly argued idea in all of paleontology. Soon the great debate among paleontologists boiled down to just a few central points, which Gould and Eldredge (1977) nicely summarized on the fifth anniversary of the paper’s release. The first major discovery was that stasis was much more prevalent in the fossil record than had been previously supposed. Many paleontologists came forward and pointed out that the geological literature was one vast monument to stasis, with relatively few cases where anyone had observed gradual evolution. If species didn’t appear suddenly in the fossil record and remain relatively unchanged, then biostratigraphy would never work—and yet almost two centuries of successful biostratigraphic correlations was evidence of just this kind of pattern. As Gould put it, it was the “dirty little secret” hidden in the paleontological closet. Most paleontologists were trained to focus on gradual evolution as the only pattern of interest, and ignored stasis as “not evolutionary change” and therefore uninteresting, to be overlooked or minimized. Once Eldredge and Gould had pointed out that stasis was equally important (“stasis is data” in Gould’s words), paleontologists all over the world saw that stasis was the general pattern, and that gradualism was rare—and that is still the consensus 40 years later.

The debate was less than a decade old when I was wrapping up my dissertation work in 1981. In my dissertation on the incredibly abundant and well preserved fossil mammals of the Big Badlands of the High Plains, I had over 160 well-dated, well-sampled lineages of mammals, so I could evaluate the relative frequency of gradualism versus stasis in an entire regional fauna. I also had a wide geographic spread (from Montana and Saskatchewan to Texas, but mostly in the Dakotas, Nebraska, Wyoming, and Colorado). I had large fossil samples of many species, with dozens at each level, and excellent stratigraphic data. When I finally plunged in and plotted and analyzed my data carefully, it was clear that nearly every lineage showed stasis, with one minor example of gradual size reduction in the little oreodont Miniochoerus. I could point to this data set and make the case for the prevalence of stasis without any criticism of bias in my sampling. More importantly, the fossil mammals showed no sign of responding to the biggest climate change of the past 50 million years (the Eocene-Oligocene transition, when glaciers appeared in Antarctica after 200 million years). In North America, dense forests gave way to open scrublands, crocodiles and pond turtles were replaced by land tortoises, and the snails changed from those typical of Nicaragua to those of Baja California. Yet out of all the 160 lineages of mammals in this time interval, there was virtually no response. To paraphrase Rhett Butler, “Frankly, my dear, the mammals don’t give a damn.”

This result intrigued me, so I began to re-examine the uncritical acceptance of the notion that fossil mammals track environmental changes. It occurred to me that our excellent database of North American fossil mammals and global climate change might be a good place to test this hypothesis. In a 1999 paper, I argued that for the four biggest independently documented periods of climatic change in the past 50 million years, the mammals either do not respond at all, or show much less speciation and extinction than they do at times when there is no evidence of climatic change. One interval included the middle-late Eocene climate change at 37 million years ago, when turnover was merely at background level, despite evidence of floral change elsewhere in North America, and a big climatic cooling event in the global oceans. The second was the Eocene-Oligocene transition just discussed. The third was the great expansion of modern grasslands at 7.5 million years ago, long after mammals with high-crowned grazing teeth appeared at 15 million years ago. In fact, there is almost no significant faunal change at 7.5 million years ago. The final example is the last 2 million years of ice ages, when climate changed dramatically, but speciation did not occur in response to climate. Instead, most ice age mammals simply migrated north and south in response to the movements of the ice sheets.

About six years ago, I decided to test this last idea. Back in 2006, I had a bunch of excellent students in my paleontology classes at both Occidental and Caltech, and several wanted to do research with me. I was at a loss over how to supervise so many undergraduates with limited backgrounds, until I realized that we could do a group of related projects practically in our back yard: the Page Museum at La Brea tar pits in Los Angeles. I equipped each one of them with calipers and gave them a measuring protocol, and got them access to the La Brea fossils through the collections managers. Then they each measured a different Ice Age mammal or bird, collecting data on hundreds of bones from all the tar pits with good radiocarbon dates: saber-toothed cats, dire wolves, giant lions, bison, horses, camels, ground sloths, plus the five most common birds: golden and bald eagles, condors, caracaras, and turkeys. After six years of work and publication, the conclusion is clear: none of the common Ice Age mammals and birds responded to any of the climate changes at La Brea in the last 35,000 years, even though the region went from dry chaparral to snowy piñon-juniper forests during the peak glacial 20,000 years ago, and then back to the modern chaparral again.

In four of the biggest climatic-vegetational events of the last 50 million years, the mammals and birds show no noticeable change in response to changing climates. No matter how many presentations I give where I show these data, no one (including myself) has a good explanation yet for such widespread stasis despite the obvious selective pressures of changing climate. Rather than answers, we have more questions—and that’s a good thing! Science advances when we discover what we don’t know, or we discover that simple answers we’d been following for years no longer work.

Clearly, it is an interesting time to be a paleontologist. As Gould (1983) put it, from the “irrelevance” of the early 1900s to the “subservient” role that George Gaylord Simpson placed us in 1944, paleontology is now in the driver’s seat, and trying to reach the “High Table” where the “High Priests” of evolution and genetics have long ruled unchallenged. Who knows where this will all end? Whatever the result, we’re clearly making advances by challenging the accepted dogmas of the time and finding their faults, and hopefully discovering something new and interesting. As Gould and Eldredge (1977) put it, “Why be a paleontologist if we are condemned only to verify what students of living organisms can propose directly?”

References

- Eldredge, N. 1985. Time Frames: The Rethinking of Darwinian Evolution and the Theory of Punctuated Equilibria. Simon & Schuster, New York.

- Eldredge, N. 1995. Reinventing Darwin: The Great Debate at the High Table of Evolutionary Theory. John Wiley & Sons, New York.

- Eldredge, N., and S. J. Gould, 1972. Punctuated equilibria: an alternative to phyletic gradualism, pp. 82-115, in Schoft, T.J.M., Models in Paleobiology. Freeman Cooper, San Francisco.

- Gould, S.J. 1980. Is a new and more general theory of evolution emerging? Paleobiology6: 119–130.

- Gould, S.J. 1982. Darwinism and the expansion of evolutionary theory. Science 216:380–387.

- Gould, S.J. 1983. Irrelevance, submission, and partnership: the changing roles of paleontology in Darwin’s three centennials, and a modest proposal for macroevolution, pp. 347-366, in Bendall, D.S. (ed.), Evolution from Molecules to Men. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Gould, S.J. 2002. The Structure of Evolutionary Theory. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass.

- Gould, S.J., and Eldredge, N. 1977. Punctuated equilibria: the tempo and mode of evolution reconsidered. Paleobiology 3:115–151.

- Prothero, D.R., 1992. Punctuated equilibrium at twenty: a paleontological perspective. Skeptic 1(3): 38–47.

- Prothero, D.R. 1999. Does climatic change drive mammalian evolution? GSA Today 9(9):1–5.

- Prothero, D.R., Syverson, V., Raymond, K.R., Madan, M., Molina, S., Fragomeni, A., DeSantis, S., Sutyagina, A., and Gage, G.L. (in press) Size and Shape Stasis in Late Pleistocene Mammals and Birds from Rancho La Brea during the last Glacial-Interglacial Cycle. Quaternary Science Reviews(in press)

- Prothero, D.R., and T.H. Heaton, 1996, Faunal stability during the early Oligocene climatic crash. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 127:239–256.

About the Author