How can one forget the dueling banjos of Deliverance? A group of urbanites goes deep into Georgia where they encounter hillbillies. One of the friendlier urbanites tries to establish a rapport with one hillbilly kid, whose countenance is creepy. He appears mentally retarded, suggested to be the result of inbreeding. Yet, he plays the banjo with great agility, to the point that he sets up a musical duel with the guitar playing urbanite. This is only a foreshadow of what will come later: the inbred hillbillies perform all sorts of sadistic acts against the urbanites.

The Ultimate Taboo

In this era of identity politics there is great concern for African-Americans, Latinos, Muslims, the LGBTQ community, and other groups, but nobody seems to care much about the degradation of Appalachian mountaineers in media and cultural portrayals. As far as everyone else is concerned, their incestuous ways make them seemingly subhuman. Indeed, incest has been the easiest means of character assassination throughout history, as the cases of Oedipus, Marie Antoinette, Anne Boleyn and so many others seem to illustrate. And there is the recurrent cultural trope that once relatives mate civilization collapses. Colombian novelist Garcia Marquez eloquently portrays this in his depiction of the Buendia family in One Hundred Years of Solitude, in which the Buendia family persists for centuries until two distant relatives have sexual intercourse leading to a child with a pig tail, and the disappearance of the ancestral Macondo village.

The incest taboo can be counted as one of the truly universal human institutions.1 Yet, there is disagreement about how far this prohibition should go. There is the universal prohibition for someone to have sex with his/her siblings, parents or grandparents, but there are variations regarding cousins, uncles, and others on the family tree. More important, there is also disagreement about what the rationale for the incest taboo is. This latter point was tested in a well-known experiment by the psychologist Jonathan Haidt in which he presented subjects with the following scenario:

Julie and Mark are brother and sister. They are traveling together in France on summer vacation from college. One night they are staying alone in a cabin near the beach. They decide that it would be interesting and fun if they tried making love. At the very least it would be a new experience for each of them. Julie was already taking birth control pills, but Mark uses a condom too, just to be safe. They both enjoy making love, but they decide not to do it again. They keep that night as a special secret, which makes them feel even closer to each other. What do you think about that? Was it OK for them to make love?2

Haidt made sure that, in this scenario, there would be no biological risk, not even social or psychological risks. Yet, the overwhelming majority of subjects answered that it would be wrong for Julie and Mark to make love. When Haidt asked them why exactly it would be wrong, subjects were unable to articulate a clear argument. Instead their response was more of an intuitive repulsion captured in the common response “yuck.”

To my knowledge, Haidt’s experiment has not been reproduced in other cultural settings, or with additional variations amongst Americans. But we may venture to make two hypotheses, which could be tested in future studies. First, Haidt will get the same results cross-culturally. With great likelihood, all human beings are repulsed by sibling incest, regardless of the alleviating factors considered by Haidt. Second, if Haidt posited that Mark and Julie were cousins (not siblings), most Americans would still likely be repulsed, but people from other regions of the world (especially the Muslim world and India) would likely not be.

In many societies cousin marriage is decidedly not considered incestuous (10% of marriages in the world are between first and second cousins; in India it is close to 40%; in Pakistan it is around 50%3), and in many cultural settings it is very functional—it eases tensions amongst in-laws, it allows spouses to accommodate to their new home, it lowers the price of dowry, etc. Yet, somehow, Americans are overwhelmed by its yuckiness and remain scandalized at the thought of first cousins marrying. Indeed, the United States is one of the few countries in the world (along with not-so-democratic countries such as China and North Korea) to outlaw cousin marriage (in 24 states it is illegal).4 It is thus necessary to set the record straight and ask: how truly dangerous is cousin marriage, and should it be legalized?

Why Evolution Pressured Against Incest, but Not Against Consanguinity

For some time, anthropologists wanted nothing to do with biology. It was the heyday of the culturalists who argued that there is no human nature, that society (and not genes) forms individuals, and the rest of the blank slate dogma. In this context, anthropologists came to believe that although incest is universally rejected, it is not due to biological factors.

Already in the 19th century, E.B. Tylor argued that incest is prohibited for strictly social reasons. According to his theory, human groups have always tried to establish relations with other groups, and the way to do it is by forcing individuals to marry outsiders, and thus form alliances. In Tylor’s memorable words, one has the option to “marry out or die out” as a result of isolation.5

In the 20th century, Claude Lévi-Strauss was also interested in how societies exchange things, and he came to believe that the incest taboo encourages exchanges of women among groups, and this in turn strengthens alliances.6

Thus, in this interpretation the incest taboo is the result of social pressures, and as far as these theoreticians were concerned incest is not even biologically dangerous, only socially so. In fact, so it was claimed, humans were originally incestuous, and only when culture appeared did they begin to marry out. Sigmund Freud even believed that our biological instincts are incestuous, but civilization intervenes to repress our Oedipal desires, which never truly go away.7

Yet, one particular theoretician was ignored for a long time. Edward Westermarck posited that we have biological drives, not towards sexually pairing with our closest relatives, but rather to feel sexual repulsion towards them. Westermarck realized that incest is indeed dangerous (although he did not have a full genetic understanding of why this might be the case), and that evolution selected for a mechanism that ensured that we would never feel sexual attraction for those that have been raised with us since infancy.8

Westermarck was ultimately proven right. For example, genetically unrelated children who are raised together in Israeli kibbutzim very rarely marry or even have sexual relations with each other later on as adults.9 In Taiwan, there is a cultural custom in which very young girls are raised together with their future husbands; in turns out that, compared to the rest of the population, these marriages have far lower fertility rates and far higher divorce rates.10

This phenomenon, now known as the Westermarck Effect, makes perfect evolutionary sense. Incest is dangerous because it increases the chances of deleterious recessive genes becoming manifest. Most deleterious genes are recessive (that is the only way they can be preserved in the gene pool), meaning that having one copy is not enough for the gene to be expressed. Incest decreases the variability that protects the gene pool in case deleterious recessive genes appear. Species that practiced incest likely went extinct (proliferation of recessive genes would make them unfit), and for survival evolution had to come up with a mechanism that ensured that incest would be avoided. It could have been sexual avoidance based on kin recognition, but in our case the mechanism actually turned out to be a form of imprinting: we tend to feel sexual repulsion for those whom we have constantly been exposed to since an early age. At the time the incest taboo was thought to be strictly social, anthropologists believed that non-human animals mated with their close relatives. We now know that, at least in the case of most primates, close relatives do practice sexual avoidance, thus further proving Westermarck right.11

Therefore, it can be safely said that natural selection pressured against incest. But not necessarily against mating with more distant relatives, or as some may call it, consanguinity. In fact, although consanguinity may also carry the risk of proliferating recessive genes, this may be outweighed by other selective advantages.

Similarity of traits in parents may turn out to be advantageous for various reasons. For example, if a woman with Rh- factor pairs with a Rh+ man, their child may be Rh+, and this can create complications in pregnancy and delivery. Instead, if that woman pairs with, say, a first cousin, there are higher probabilities that such a man is also Rh-, and therefore that also increases the chance that the child will be Rh-, thus avoiding the pregnancy and delivery complications. Renowned geneticist Patrick Bateson offers a more colorful example:

The size and shape of teeth are strongly inherited characteristics. So too are jaw size and shape… The potential problem arising from too much outbreeding is that the inheritance of teeth and jaw sizes are not correlated. A woman with small jaws and small teeth who had a child by a man with big jaws and big teeth lays down trouble for her grandchildren, some of whom may inherit small jaws and big teeth. In a world without dentists, ill-fitting teeth were probably a serious cause of mortality. This example of mismatching, which is one of many that may arise in the complex integration of the body, simply illustrates the more general cost of outbreeding too much.12

Anthropologist Robin Fox adequately sums up the argument: “So nature aims for a middle ground: organisms breed out to avoid losing variability, but not so far out that they dissipate genetic advantages. In human terms this means that the immediate family is taboo, but that marriage with cousins should be preferred.”13

There may be an additional reason why natural selection favored consanguinity. The renowned evolutionary biologist W.D. Hamilton proposed that the intensity of altruism correlates with the degree of genetic proximity. This argument has been expanded by some theoreticians into saying that if an animal mates with a genetically close partner, their offspring will also be genetically closer to the parents, and this will ensure greater intensity of altruism and care from the parents to the offspring, which is a significant evolutionary advantage. This mechanism includes humans, and therefore, we evolved a preference for mating with partners that may be genetically closer to us.14

In fact, it has long been noticed amongst human and non-human animals that individuals with similar phenotypes mate with one another more frequently than would be expected under a random mating pattern. This phenomenon, known as assortative mating, may be behind preferences for consanguinity. Cousins may not necessarily look similar (i.e., have similar phenotypes), but they often do, and in that regard, they may feel more attracted to each other.

So, we may expect that, given our natural disposition, we feel sexual repulsion for parents and siblings, but sexual attraction for cousins and other more distant relatives. Perhaps Elvis was right when he sang about Kissin’ cousins. Indeed, he was. It has been estimated that about 80 percent of all marriages in human history have been between cousins.15 If natural selection primed us for cousin marriage, and if it offers some evolutionary advantage, then the biological arguments against its legality (appealing to its dangerous biological consequences, as it is often done) lose strength.

What the Data Actually Says

Evolutionary theory (and evolutionary psychology in particular) has been criticized as being too speculative. Evolutionary explanations may be very coherent, but we still need to take a look at what the data actually says. We may understand why evolution primed us to avoid siblings but feel attraction for cousins, and how that may have made us fitter, but we still need to know whether or not there is a danger to cousins marrying. The substantial majority of human beings have mated with their first cousins, and we appear to be fine, so it would make sense to argue that, as a whole, cousin marriage is not especially dangerous. But, on the other hand, it is nevertheless true that when genetically related individuals mate, the chances that their offspring will have a higher degree of homozygosity (having the same copies of genes) increases, thus increasing the probability of having more recessive deleterious genes.

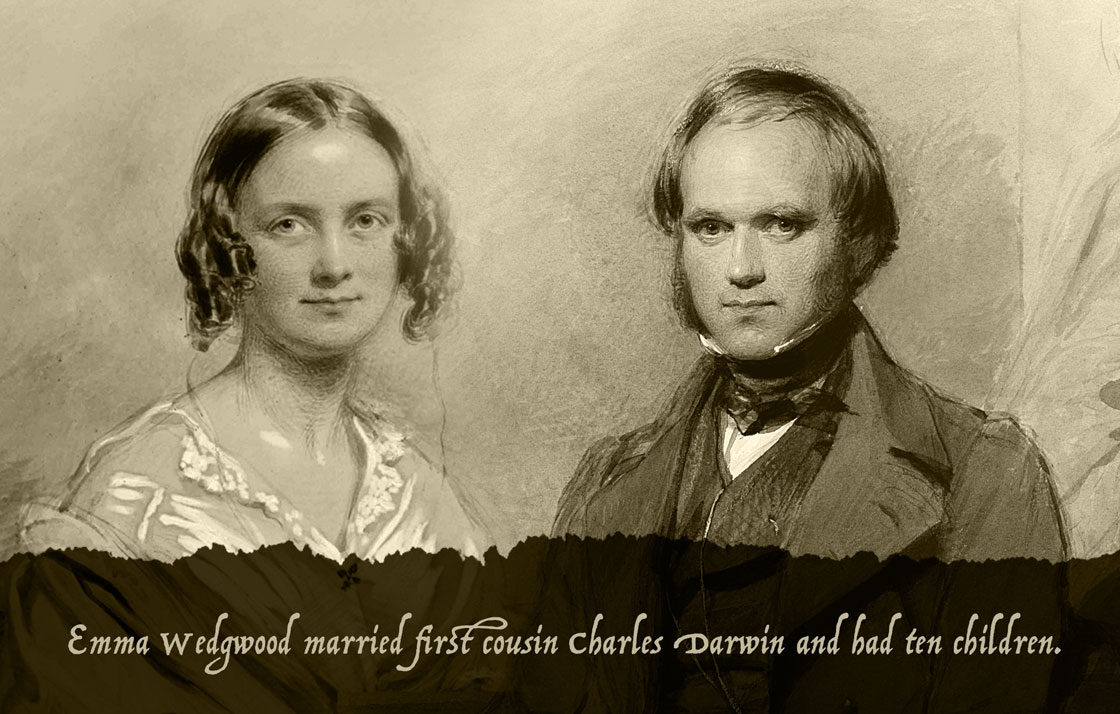

At the time anthropologists were beginning to discuss what the reasons for the incest taboo were, Charles Darwin wondered not just whether incest would be dangerous, but also cousin marriage. He was in fact married to his first cousin Emma, and he worried that particular fact might affect his descendants.

One of Darwin’s sons, George, sought to study this question thoroughly in 1870. He paid special attention to mental asylums. He reasoned that if cousin marriage had the deleterious effects it allegedly did, then first cousin mental patients would be overrepresented in those institutions. It turned out not to be the case: only 3–4 percent of mental patients were the offspring of first cousins, roughly the same percentage of England’s general population at the time. When George communicated these findings to his father, Darwin replied: “For Heaven’s sake… put a sentence in some conspicuous place that your results seem to indicate that consanguineous marriage, as far as insanity is concerned, cannot be injurious in any very high degree.”16

Recent studies have more nuanced conclusions. After doing extensive metanalyses, the National Society of Genetic Counselors concluded that, overall, cousin marriage increases the risk of children with genetic defects by 1.7 percent,17 roughly the same added risk as a 40-year old woman having a child. Thus, there is an additional risk in cousin marriage, but given its limited scope, it does raise the question of whether cousin marriage should remain illegal, as it does in almost half the states in the United States. If no law forbids a woman in her 40s to have children, why should cousins be forbidden to engage in a practice that carries the same risk? Prohibitions of cousin marriage are obviously a form of eugenics; whatever one may think of eugenics it should at least be consistent, but it is clear that allowing someone with Huntington’s disease to get married, but not allowing cousins to do the same, is far from moral consistency.

It may seem surprising that cousin marriage only adds a 1.7 percent risk factor given the frequent media reports of cases of communities where cousin marriage is rampant, and as a result, the rate of genetic defects is alarming. Perhaps the most notorious case is that of ethnic Pakistanis in the United Kingdom: about 50 percent of British Pakistanis marry their first cousins, and children in those communities are 10 times more likely than the general British population to be born with defects.

Yet, as Diane Paul and Hamish Spencer argue, “British Pakistanis, are often poor… The mother may be malnourished to begin with, and families may not seek or have access to good prenatal care, which may be unavailable in their native language. Hence, it is difficult to separate out genetic from socio-economic and other environmental factors.”18 Thus, when British Immigration Minister Phil Woolas claimed that cousin marriages produce lots of significant genetic problems, he was extensively rebuked by scientists because the evidence is simply not conclusive.

There are additional factors to consider, such as the founder effect. Whatever the genetic conditions of the founders of any given population are, they will be magnified. If the founders did not have a significant number of deleterious recessive genes, then the population, even if it practices inbreeding, will be fine. In fact, it will even be likely that it will increase its fitness, as the good genes of the founders will now be magnified. This is what seems to have been the case with the Rothschilds, the famous banking family that has frequently practiced cousin marriage, and remains highly successful with no known genetic problems.

On the other hand, if the founders had deleterious genes, then inbreeding will magnify their expression. This was the case with another famous but not-so-successful family, the Hapsburgs. These royals practiced inbreeding for many generations and as a result many family members developed the prominent “Hapsburg jaw.” One of them, Charles II of Spain, was born with serious genetic defects, thus ending Hapsburg rule in Spain in the late 17th century. The fate of the Hapsburgs (at least regarding the jaw) was probably set by the founder effect of Maximilian I, an emperor in the 15th century with the prototypical Hapsburg jaw, when the family had still not begun to practice cousin marriage extensively.

Likewise, the risks of cousin marriage have a cumulative effect. The Hapsburgs soon developed their prognathic jaw, but the effects of inbreeding became more pronounced (by the time of Charles II) when various generations practicing inbreeding accumulated the deleterious recessive genes. Thus, two first cousins whose families have not consistently inbred in the past, are relatively free of risk should they decide to marry.

So, Why is Cousin Marriage Illegal in Some States?

We may thus agree that the repulsion for parent-offspring and sibling incest has a strong biological basis, and for that very reason, it is universal. In contrast, the repulsion for cousin marriage is not universal, and consequently, it does not seem to have a biological basis. Indeed, it does not. Many societies favor cousin marriage, but only when it is of the cross variety (a man marries his father’s sister’s daughter, or his mother’s brother’s daughter), and abhor the parallel variety (a man marries his father’s brother’s daughter, or his mother’s sister’s daughter). In some other societies, it is the opposite. Be that as it may, it is biologically arbitrary, as both parallel and cross cousins have the same genetic coefficient of relationship (12.5 percent). If these societies were concerned that cousin marriage has serious biological risks, they would forbid all first cousin marriages, yet they do not.

Cousins should not be encouraged to marry, in the same manner that women over 40 should not be encouraged to become pregnant. But, neither should they be forbidden.

Americans who say “yuck” when considering the idea of cousin marriage may try to rationalize it on biological grounds. But the truth is that there are deeper cultural reasons, as Martin Oppenheimer extensively documents in his definitive history of cousin marriage in the United States, Forbidden Relatives.19 As the United States expanded its territory and power in the latter half of the 19th century, it did so under the banner of Manifest Destiny. This was a religious idea (God entrusted America with that mission), but it also had a secular goal. Not unlike the mission civiliatrice of French colonialism, the justification for expansion was to bring civilization to “savage” peoples.

One particular anthropologist, Lewis Henry Morgan, believed that humans in their uncivilized state were an incestuous horde, and one key aspect of civilization was about establishing incest taboos. (Both Freud and Lévi-Strauss were deeply indebted to Morgan regarding their ideas about the origins of civilization). Although himself married to his own first cousin, Morgan seemed to believe that first cousin marriage was still a remnant of that barbarous incestuous past. Ultimately, Americans eager to civilize savages, embraced this idea. It is not difficult to see how Deliverance fits into this narrative: the civilized urbanites would never even think of marrying their cousins; the barbarous hillbillies are all inbreds.

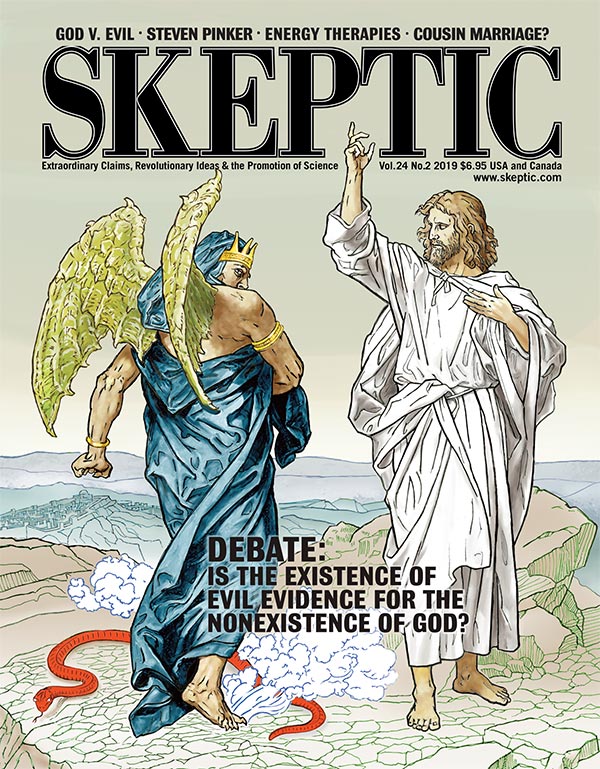

This article appeared in Skeptic magazine 24.2

Buy print edition

Buy digital edition

Subscribe to print edition

Subscribe to digital edition

Intellectual elites attributed cousin marriage to savage people, typically the poor. Yet in the United States there was also a democratic aspect to this. It was also noted that cousin marriage was a despicable practice of the royalty and the nobility, the type of European institution that American republicanism rebelled against. Furthermore, as modern political institutions were consolidated in the post-Civil War period, States were given the power to regulate private affairs as a whole. The illegality of cousin marriage was taken as a significant modernizing step, cloaked with scientific data (which, as we have seen, is actually rather faulty), with the same crooked authoritarian and paternalistic attitude that also gave rise to the eugenic movement some decades later (and with the same faulty science as support). Thus, this is how cousin marriage became illegal in some areas of the United States.

That risk, although much smaller than originally believed, is nevertheless there. And for that reason, cousins should not be encouraged to marry, in the same manner that women over 40 should not be encouraged to become pregnant. But, neither should they be forbidden. At best, public policy should encourage (but again, not force) cousin couples to undergo genetic testing, in order to consider the risks on a case-by-case basis, and ultimately, let them decide on their own. In this age of hypersensitivity and political correctness, the idea of Manifest Destiny is offensive to many. But at least, the overwhelming majority of Americans still like to think of their country as the “Land of the Free.” A country where you cannot marry your cousin is not fully free. It is time to change that. ![]()

About the Author

Dr. Gabriel Andrade was born and raised in Maracaibo, Venezuela. He received a Ph.D. from University of Zulia (Venezuela). He currently teaches Ethics and Behavioral Science at St. Matthew’s University School of Medicine (Cayman Islands). He previously taught at Xavier University School of Medicine (Aruba), College of the Marshall Islands (Republic of the Marshall Islands) and University of Zulia (Venezuela). He has published some academic articles in English, and many books in Spanish.

References

- Brown, Donald, 1991. Human Universals. New York: MacGraw Hill.

- Haidt, Jonathan, 2001. The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychological Review, 108, 814–834.

- “Global prevalence tables” 2019. Available at: www.consang.net

- State Laws on Marriage to Cousins. The Washington Post. https://wapo.st/2I6Eqcv

- Bolin, Ann and Whelehan, Patricia. 2009. Human Sexuality: Biological, Psychological and Cultural Perspectives. New York: Taylor and Francis, 194.

- Lévi-Strauss, Claude, 2016. The Elementary Structures of Kinship. New York: Beacon.

- Freud, Sigmund, 1998. Totem and Taboo. New York: Dover.

- Westermarck, Edward, 2007. The History of Human Marriage. New Delhi: Logos.

- Durham, William. 1991. Coevolution: Genes, Culture, and Human Diversity. Stanford University Press, 310.

- Wolf, Arthur, 2013. Incest Avoidance and the Incest Taboos. Stanford University Press, 48.

- Dixson, Alan, 2012. Primate Sexuality: Comparative Studies of the Prosimians, Monkeys, Apes, and Humans. Oxford University Press, 120.

- Bateson, Patrick, 2005. Inbreeding Avoidance and Incest Taboos. In: Wolf, Arthur (Ed.). Inbreeding, Incest, and the Incest Taboo. Stanford University Press, 25–26.

- Fox, Robin, 2011. The Tribal Imagination. Harvard University Press, 131.

- Salter, Frank. On Genetic Interests. 2006. London: Transaction.

- Howe, Tasha. 2011. Marriages and Families in the 21st Century: A Bioecological Approach. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 212.

- Kuper, Adam, 2009. Incest and Influence. Harvard University Press, 98.

- Benett R.L., Motulsky A.G., Bittles A., 2002. Genetic counseling and screening of consanguineous couples and their offspring: recommendations of the national society of genetic counselors. J Genet Couns;11(2):97–119.

- Paul, Diane, Spencer, Hamish, 2008. “It’s Ok, We’re Not Cousins by Blood”: The Cousin Marriage Controversy in Historical Perspective. Plos Biology. DOI: https://bit.ly/2DsH72D

- Oppenheimer, Martin, 1996. Forbidden Relatives. University of Illinois Press.

This article was published on July 23, 2019.

As genetic testing becomes more prevalent and knowledge of specific genes increases, it should be possible to test for specific allele-matching problems, whether the lines of descent are known or not. You may have to supply your complete DNA to your iphone dating app, which will alert you to specific potential problems.

Interesting article on a subject I’ve done some reading on, most notably another book of Robin Fox not cited, “The Red Lamp of Incest.” From this I add three comments:

1) Fox, contrary to what the article author asserts, claims there “is no universal horror” of incest, mentioning, for example, ancient Egyptian sibling marriage. (Though probably they should have been bothered.)

2) Teens, he stated, unlike anthropologists, distinguish sex from marriage. Incestual sex (however defined) is more common and accepted than incestual marriage.

3) Fox himself, though a bio-anthropologist (or sociobiologist), recognizes both genetic and cultural reasons for incest taboos. While the deleterious recessive gene theory is significant, it is also significant that human bands which traded with each other were more likely to survive. Indeed, Fox describes us as a species as being defined in part by our propensity to trade. One of the “items” human groups have traded for most of our prehistory was women. It was to a band’s advantage to have relatives in neighboring bands for these were groups that would be more likely to aid you in times of need (to help preserve your own genes).

Fox’s views a side, there are some other important considerations not mentioned in the article. The famous kibbutzim example, used as support for Westermarck’s ideas have another explanation overlooked because when it is cited, critical details are omitted. The children in the Israeli 1960s kibbutzim were raised collectively, not merely as one big happy American-style family. The sexes lived together, bathed together, and were allowed to experiment erotically together. An alternative hypothesis for the alleged Westermarck effect in this instance is that, while young, prepubescent girls are capable of orgasm during their erotic explorations with the kibbutzim’s boys, the little boys are not. Thus, associating sexual frustration with the children you grew up with could instead have been a reason they were unlikely to marry later in life. (And one ought to investigate whether when the children came of age, did they become aware of the greater Israeli society around them which condemned and made them ashamed of their juvenile sexual practices?)

The author also did not note that among the US states that do allow first cousin marriage, some of them require that at least one of the partners be sterile. This prompts the distinction between cultural incest and biological incest. The former includes prohibitions on sex and marriage between people who are not genetically close, such as relations with your wife’s sister (either after your wife’s death or as another wife in polygamous societies). Yet other cultures would prefer this arrangement. Biologically, any form of non-reproductive erotic activity could be considered non-incestuous, but cultures tend not to look at it that way. One book I read described a case of suspected mother-daughter “incest” where the American mother was accused of sexually molesting her young daughter. If it had been true (the book’s author said the allegation was false), it would have been child molestation, yes, but incest, when there is no chance of pregnancy? But such is the illogic of cultural definitions of incest.

The author seems to differentiate incest from consanguinity. To be clear, incestuous sexual relations are also consanguineous sexual relations, but the reverse is not necessarily true. Consanguineous simply means you share relatively close genetic relations, like the members of your extended clan. Relatives like your siblings or parents are certainly consanguineous; the term is not restricted to more distant relatives.

While the author of the article keeps on mentioning women over 40 as having birth defect risks as great as first cousin parenting, he fails to mention the risks associated with old men procreating. The older we men are, the greater chance the sperm we produce will be defective. I forget which biological luminary said it, but he quipped that the greatest threat to the genetic integrity of the human species is fertile old men.

I googled up the hillbilly banjo player from Deliverance. He was neither a savant nor disabled in any way. He was a 15 year old kid that was cast as the character. He didn’t even play the banjo. ! The filmmakers used makeup to alter his appearance.

Typo — ” future husbands; in turns out that, compared to the rest of the population” IT turns out?

Interesting article . . . . otherwise ;)

I read this article with great interest and it was relevant to a family that is very close to my family. Two first cousins got married and I was concerned about the chances of birth defects. I did some research and happily found that – as the author wrote in this article – the chances of birth defects is only a couple of percent – comparable to births by women over 40.

I noted that my extended family has many academicians in it and consequently has a number of children born to women in their 40’s. A few of us – from both families – discussed this and in their culture 40 is too old for having babies (for several reasons, like such old parents would not be able to help much with grandchildren – or great-grandchildren).

It was an interesting discussion. I am happy to report that, so far, neither family has birthed any banjo-players.

Pity all my cousins are as ugly as I am.

I expect that one of the reasons the growth of human population was so slow, why life spans were so short and why entire communities disappeared is because incest was built into much of human society for so long. When scattered small communities were the norm and intermingling of populations was hampered by lack of travel ability & active cultural discouraging of intermingling was strong there was little growth in overall population size.

‘Racial purity ‘ wasn’t an idea that started with Nazis.