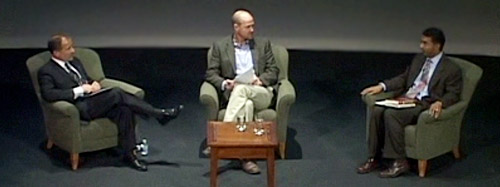

left to right: Michael Shermer, William Lobdell & Dinesh D’Souza

The Great Debate: D’Souza v. Shermer

Is Religion a Force for Good or Evil? and

Can you be Good Without God?

In this debate on what are arguably two of the most important questions in the culture wars today — Is Religion a Force for Good or Evil? and Can you be Good without God? — the conservative Christian author and cultural scholar Dinesh D’Souza and the libertarian skeptic writer and social scientist Michael Shermer, square off to resolve these and related issues, such as the relationship between science and religion and the nature and existence of God. This event was one of the liveliest ever hosted by the Skeptics Society at Caltech, mixing science, religion, politics, and culture.

Church-State Update for the New Year

Skepticality welcomes 2008 with an update from the Secular Coalition for America’s Lori Lipman Brown — the only lobbyist dedicated solely to the concerns of secular humanists and non-theists and to the preservation of the separation of church and state.

Lori talks with Derek & Swoopy about why 2007 was the best year yet for the SCA, the top issues on the agenda for 2008, and how the current presidential candidates stack up on the issues important to skeptics.

new Lectures at Caltech on DVD

- The Great Debate: Is Religion a Force for Good or Evil?

and Can you be Good without God?

Dr. Dinesh D’Souza v. Dr. Michael Shermer - The Bible Against Itself: Who Wrote the Bible & Why it was Written

by Dr. Randel Helms - Geology, Creationism & Evolution: The Breathtaking Inanity of Flood Geology

by Dr. Donald Prothero - PLUS, our clearance on ALL VHS format videos continues at $7.99 each.

(The above lectures are not available on VHS).

In this week’s eSkeptic Steve Fuller responds to Norman Levitt’s Review of Science vs. Religion?: Intelligent Design and the Problem of Evolution (Polity Press, 2007, ISBN 0745641229). Steve Fuller is a Professor of Sociology at University of Warwick.

READ the original review which ran in eSkeptic a few weeks ago.

Steve Fuller Responds to Norman Levitt’s Review of Science v. Religion

I confess that I am not entirely convinced that Norman Levitt has read Science v. Religion? What passes as a review of the book consists of a smattering of his own preoccupations that make passing contact with things I say, sandwiched between boilerplate versions of his now trademark fulminations. At no point does he state, let alone answer, the fundamental thesis of the book, namely, the centrality of intelligent design in motivating the scientific enterprise, in terms of which Darwin’s theory of evolution is a historical aberration. (That much should be apparent from the book’s subtitle: Intelligent Design and the Problem of Evolution.) The book is not meant as a detailed defense of the versions of ID put forward by Dembski and Behe, but rather an attempt to show that there is much more to their ideas and instincts than the intellectually claustrophobic discussion to date would suggest.

Consider his treatment of what I say about complexity, which indeed figures in a title of a chapter in my book, though at most five pages are of direct relevance to Levitt’s concerns. First, I claim that it is impossible to design a true random number generator because it is ultimately possible to infer the algorithm. Levitt responds that in practice it’s easy to design algorithms that generate data that people cannot determine if they are random. He then goes on to observe that the chance-based character of evolutionary processes can be mimicked on computers, with random elements simulated by introducing outcomes of unrelated processes.

I know all this, and nothing in my discussion denies or displays ignorance of it. At most, I may be guilty of imprecise expression, for which I duly apologize. Where Levitt and I genuinely disagree is on the implications of all this for ID. As far as I can tell, all that Levitt demonstrates is how well intelligent design (in this case, by humans) can generate processes that do not seem to be intelligently designed. His examples only cut against versions of ID that involve a completely preprogrammed conception of design with no prospect for fundamental change once the program is run. This may have been Paley’s version of ID. I am not sure who upholds it now, though I certainly don’t. That the universe is intelligently designed need not imply that God micromanages it from moment to moment.

The relevance of this point — the most substantial one in Levitt’s entire review — to my overall thesis is that the very idea that we might successfully simulate significant aspects of how the universe works presupposes our ability to adopt the standpoint of someone who could have created the universe, the great cosmic programmer. This presupposition is far from self-evident. It historically depended on humans believing they were created in the image and likeness of God. Of course, this does not prove God’s existence. But those who took the idea into science, including the original theorist of the computer, Charles Babbage, and his great Cambridge predecessor Isaac Newton, saw it very much as a vindication of ID. The challenge faced by those who would minimize the assumption of ID in nature is whether the scientific enterprise can be motivated solely by its sheer empirical success. Levitt says nothing about this. However, Levitt claims to say something about Newton — what exactly is unclear. On two points we are in agreement: Newton was a Biblical literalist who thought he could get into God’s mind, and his theism contributed to inserting God into physics where it was not necessary. But Levitt also appears to think the latter counts against the former. If this passes for an argument against methodological supernaturalism, then Darwin’s botched understanding of heredity should count against methodological naturalism (which Levitt misnames “materialism”). In both cases, a metaphysical commitment that served a scientist well for much of his research came up short when overstretched. This is only to be expected, given what William Whewell originally called the “heuristic” function of metaphysics as providing broad but fallible access to a domain under scientific investigation. There is nothing especially damning about Newton’s failure to recognize his own fallibility. It happens all the time, which is why science only works as a collective enterprise.

Levitt also mistakenly thinks that I am trying to mask what he calls Newton’s “dogmatism” (a curious word given the semi-secrecy of Newton’s religious views) by casting him as a Unitarian. Had Levitt read my book a bit more carefully, he would have noticed that the relevant feature of Newton’s Unitarianism that motivated subsequent generations of scientists — I pay special attention to Joseph Priestley — is what is sometimes called “perfectibilism”, the Christian heresy that humans through their own will and intellect might become God. This is the radical implication of deus absconditus that Levitt misses. In the 20th century, this orientation animated such pioneers of artificial intelligence as Warren Weaver, Norbert Wiener, and Herbert Simon. I count these people as ID theorists just as much as Dembski and Behe.

Turning to evolution itself, Levitt claims I take the Neo-Darwinian synthesis to be “delusional” because I describe it as a rhetorical achievement. This simply shows that Levitt holds rhetoric in much lower esteem than I do. (A better word than “delusional” would be “contingent”.) He also presumes falsely that rhetoric is to be contrasted with the hard graft of science, on the basis of which he then suggests that I deny the latter to evolutionists. No, I simply deny that there is a principled difference between rhetoric and science. They go hand in glove. It is here that I am perhaps most “postmodern”. In Levitt’s words, if I am “hard-pressed to hide [my] scorn for actual scientists”, then that is because I have no scorn to hide. Levitt is the one who finds the rhetorical character of science unbearable — so much so that he quotes me on p. 123 as saying the exact opposite of what I wrote.

As for my alleged failure to provide a “serious analysis of the working methods and logical structure of biology itself”, I despair that Levitt missed the point of my discussion, which is not to show that the Neo-Darwinian synthesis is empirically fraudulent or logically incoherent — in which case his charge would have some merit — but rather to show that the constitutive fields of biology can, and for the most part do, conduct their research activities without having to take a principled stance on evolution vs. ID. Other than denigrate the significance of the Nobel Prize (which I offered in support of this claim), Levitt says nothing of relevance here.

Let me end by addressing Levitt’s boilerplate remarks about the politics of all this. First, whether or not my views are correct, I fail to see how they count as “antiscience”, unless one simply identifies “science” with orthodox scientific opinion. In fact, Levitt does this in his review but that, to my mind, is a step too far in the direction of relativism, if not authoritarianism. This raises the larger issue of how someone like Levitt — and he is far from alone — squares a commitment to liberalism, if not leftism, and relentless campaigns of vilification and demonization of those who would challenge the status quo in science. In my own case, Levitt’s allegations about hidden right-wing theocratic alliances are, to borrow one of his favorite words, “delusional”.

As any student of the history of science knows, challenges to the status quo often originate in strange, sometimes even unsavory, quarters. After all, Darwin’s own theory was kept afloat for its first half-century largely by an unholy alliance of capitalists, eugenicists, free-floating racists, and wishful theologians. The trick is for the challenger to expand from its initial base and secure the support of the broader scientific community. Darwin’s theory has certainly done that; ID has not. My book was written to show that there are good historical reasons for believing that ID’s scientific constituency could well extend beyond the offices of the Discovery Institute. Why Levitt should fear this prospect to such an extent that it compromises his critical judgment remains a mystery to me.

Every week, we’ll be adding new content to MichaelShermer.com and we’ll announce those additions here. You can also stay up-to-date by subscribing to the RSS feed.