In this week’s eSkeptic:

What really happened in Mattoon, Illinois in September, 1944? In this week’s eSkeptic, we present an article culled from a 1994 issue of Skeptic magazine (volume 3, number 1) which marked the 50th Anniversary of the Mattoon Phantom Gassing. In one of the most poignant examples of social influence and mass hysteria in history, the story of the Phantom gasser of Mattoon Illinois reveals what happens when people come to believe something for which there is no proof.

Mad Gasser Illustration (directly below) copyright © 2010 Aidan Wilson. Used with permission.

Was the Famous Mass Hysteria

Really a Mass Hoax?

by Willy Smith

The main claim to fame of Mattoon, a central Illinois town of about 16,000, is the alleged activity 50 years ago of a “gasser” never apprehended or identified. During a short period at the end of the summer of 1944, more precisely from August 31 to September 12, this individual, and perhaps some copycats, terrified young women by releasing some kind of gas in their rooms — gas that was never identified — and in the process he acquired the name of the “Phantom Gasser of Mattoon.”

It is truly remarkable how the episode of the so-called Phantom Gasser (sometimes referred to as the “Phantom Anesthetist”) of Mattoon has become a stanchion of contemporary popular literature, quoted in support of diversified and often unrelated hypotheses. In a recent issue of Skeptic (V. 2, #3), for example, Michael Shermer characterized it as a “splendid example of mass hysteria” (p. 56), comparing it with the witch crazes of the 17th century and the repressed-memory accusations of today, without providing many details of what actually took place in Mattoon. In the June, 1993, issue of Magonia, Roger Sandell associated it with the anti-Satanism furor:

Hysterical contagious illness leading to claims of mystery poisoners such as the Phantom Gasser of Mattoon panic in 1944, are a well established tradition, and their appearance here [quoting from A. Corburn in the New Statesman] emphasizes the similarity of the antiSatanist panic to other forms of mass irrationality (p. 13).

In the UFOlogical literature Mattoon has been used to support opposite contentions. Olmos Ballester (1977), for example, emphasizes the differences between the onset of UFO waves and the start of mass hysteria flaps, concluding that the former has an abundance of physical stimuli which are lacking in the latter, hence indirectly establishing the reality of UFO phenomena. J.R. Stewart (1977), on the other hand, quotes it to support the thesis that cattle mutilations have a naturalistic interpretation — namely, the hysteria of the farmers, rather than a bizarre explanation due to UFOs or other preposterous circumstances, thus denying the objective existence of UFOs.

Finally, in a lengthy and scholarly paper appearing in several 1984 issues of the MUFON UFO Journal, Dr. Michael D. Swords explores the psychiatric literature on the nature of “hysteria,” and ran into several surprises:

The psychiatric profession hasn’t quite made up its mind as to whether “hysteria” even exists. Some books define it as a “name once used for a variety of neuroses.” The word “hysteria” even disappeared entirely from the psychiatrist’s “Bible,” the DIAGNOSTIC AND STATISTICAL MANUAL FOR MENTAL DISORDERS, in 1952. It reappeared in the 1968 edition under several headings … The modern term Chronological Details of Mattoon Gassing Incidents Provided by Johnson for mass hysteria is “mass psychogenic illness” or MPI.

Swords then presentes four alleged cases of MPI, including the Mattoon incident, and concludes: “It is not at all clear to this author that the MPI contributes any cases of UFO reports.”

At one point I began to wonder how many of those who referenced the Mattoon incident in order to affirm one point or another had really gone to the original literature to inform themselves. In my investigation I discovered there is one and only one scholarly paper written on the subject, by Donald M. Johnson. It is my impression from examining all the data that Johnson, who at the time of writing was an undergraduate student at the University of Illinois, seems to have had the intention to “prove” a case of mass hysteria, regardless of the evidence. For example, his spin on the events begins rather inaccurately: “The story of the ‘phantom anesthetist’ begins on September 1 when a woman reported to the police that someone had opened her bedroom window and sprayed her with a sickish sweet-smelling gas which partially paralyzed her legs and made her ill” (p. 175).

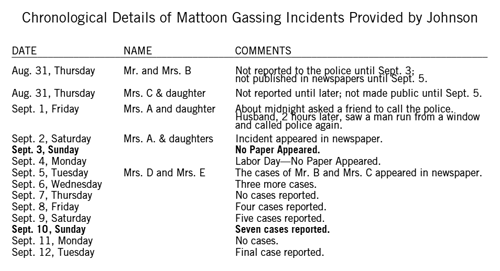

Well, not exactly. The story did not start on September 1 and the woman did not report it to the police, but to a friend and to her husband, who then called the police. This can be inferred from Johnson’s own data. He states that “on…Sunday the third, Mr. B reported to the police that he and his wife had had a similar occurrence. In the middle of the night of August 31 — the night before Mrs. A’s attack — he woke up sick, and retched, and asked his wife if the gas had been left on” (p. 176). Johnson continues, revealing there was even a second incident that preceded the claimed first event of Mrs. A: “About the same time [as Mr. B] Mr. C, who works nights, told the press that his wife and daughter had like- wise been attacked” (p. 176). In other words, Johnson has labeled the events A, B, and C, but in actuality, by his own account it goes B, C, and A. The chronology of the events in question is presented in Table 1.

From the chronology we can see that there were a grand total of 25 cases in 13 days. The weight of all these cases, however, is not the same. The case of Mr. and Mrs. B, for instance, occurring before the key case of Mrs. A (that supposedly triggered the mass hysteria), cannot be suspected, as Mr. B was the one to feel sick and smell the gas. (The mass hysteria was said to be primarily a female phenomenon.) For Mrs. C and her daughter, since the case was not reported until later, and not made public until September 5, mass hysteria is not a viable causal explanation. It seems more rational to believe that this was also a real incident. Therefore, for Mr. and Mrs. B, and Mrs. C and her daughter, it is more likely to assume the events, whatever they were, had some basis in reality, not mental delusion. Johnson offers private conversations and gossip as two modes of information exchange into the system to trigger the mass hysteria, but the proximity in time of the first two events (B and C), and the fact that they happened in the middle of the night, makes it very unlikely that word of the incidents could have spread so quickly. As they were not reported in the newspaper until two days later, they simply had to be real events.

Consider now Johnson’s key case: Mrs. A and her daughter. Around midnight of September 1, Mrs. A reported to a friend that she and her daughter had been gassed. Mr. A, coming home around 2:00 a.m. on September 2, reported to the police that he saw a man run from the window. We do not know if Mr. A knew about Mrs. A’s attack, or if either of them knew about the incidents the night before with B and C.

Without evidence that Mrs. A knew about B’s and C’s attacks, or that Mr. A knew about Mrs. A’s attack, mass hysteria cannot be proffered as an explanation. A better thesis is that a prowler was prowling (or a prankster was pranking), and scared Mrs. A and her daughter around midnight. Either he gassed them, and/or there was a gas leak in the home. Perhaps they returned to the scene two hours later when Mr. A arrived, or Mr. A saw a shadow and misinterpreted it as a prowler. Thus, the sequence of occurrences after September 2 (when this incident was reported), if it was a case of Mass Psychogenic Illness, it was most likely triggered by a real incident of some sort — prowlers or pranksters.

No judgment can be advanced for the other cases, as there are no more details. But we have made progress, as we have easily disposed of the initial incidents as natural in origin. Perhaps the others were triggered by the sensationalist handling by the media, particularly the local paper. The Mattoon Daily Journal-Gazette, the only paper with a large circulation in the city, was, according to Johnson, read at the time by 97% of the Mattoon families. There is, in fact, a curious detail here, glossed over by Johnson. The first story appeared on the front page on September 2, with the bold headline ANESTHETIC PROWLER ON LOOSE. But above one of the columns was headed MRS. A AND DAUGHTER FIRST VICTIMS. If the reporter knew about B and C, then he must have known that A was not the first. If he did not know about B and C but only about A (there were no other incidents yet), then why the “first” modifier? Johnson dismisses this as an error, but such a contention does not necessarily follow. Too many people see the headlines of a newspaper before it goes to press. This is a curious anomaly. If a prankster was involved, perhaps the newspaper was behind it for whatever reason.

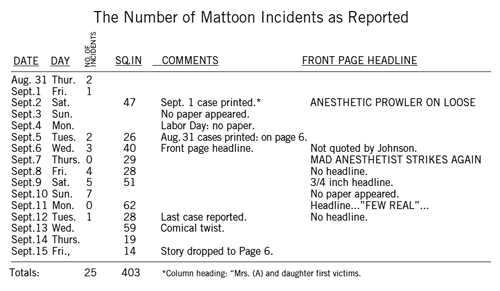

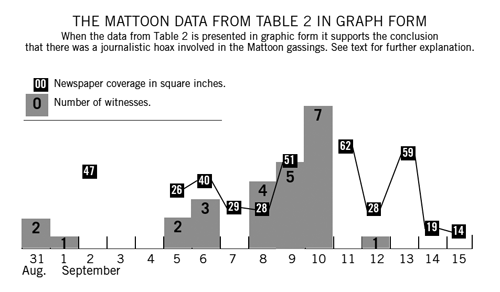

Johnson provides us with detailed statistics of the coverage of the events, in square inches of newspaper space, that offers a different interpretation. The press coverage started on September 2, when Mrs. A’s incident was reported, and continued unabated in almost every issue until September 15 when the story was dropped. The number of reported cases reached a maximum on September 10, which was the peak of police activity in their efforts to catch the culprit red handed. Only one other incident took place (September 12), and that was the end of it. Since the Journal-Gazette was still carrying the story, it is possible that if there were a prankster (or he had copycats) he was suddenly discouraged by the police attention.

Therefore, contrary to Johnson’s assertion that there were two hypotheses (real gasser v. mass hysteria) to explain the facts, there are really three: (1) MPI, or mass hysteria, triggered by the real actions of a prowler/prankster and/or a gas leak; (2) a prankster acting alone or organized by the newspaper as a prank or for more serious unknown reasons; (3) a real anesthetist.

Before discussing these possibilities in some depth, let’s take a moment to examine, as Johnson does, the nature of the reported gas used by the attacker. He says that it did not affect others in the room. This is not true when we consider B’s case (August 31), where the husband was the first to feel sick. Johnson also informs us that one of the effects reported — vomiting — was independently verified, but dismisses this as a symptom of hysteria, as he does the excited condition observed in the victims. In fact, Johnson presents the following description of a mild hysterical attack from the 19th century to support his case (p. 178):

I choose, for an example, what happens to a woman somewhat impressionable who experiences a quick and lively emotion. She instantly feels a constriction of the epigastrium; experiences oppression, her heart palpitates, something rises in her throat and chokes her… (Janet, 1901).

What Johnson apparently did not realize is that this opinion requires the a priori existence of a stimulus, and the fact is that the appearance of the symptoms as reported is prima facie evidence of the reality of the incidents. Had the victims remained calm and collected after going through such an experience, the investigator would have been correct in suspecting foul play. Since the vomiting was a fact, as well as the independent testimony of husbands that they had really smelled gas, it follows that at least the three initial incidents (August 31 and September 1), and perhaps some of the others, had a basis in reality.

From a perspective 50 years later, it is hard to make a guess as to the real nature of the gas, but from the details reported by Johnson, it is conceivable that the “gasser” simply used natural gas that he either carried or that he had just released from sources existing at the homes he visited.

illustration by Jean Paul Buquet-Banzali

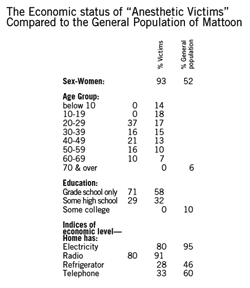

Johnson’s experience in sociology was probably no more than an introductory course (The official records at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign show that Donald Max Johnson graduated on June 15, 1952, with a Master’s degree in Education. In 1944, he was most likely a freshman, with marginal qualifications for making such a serious sociological interpretation of mass hysteria. He was, perhaps, guided along in his interpretation of the data by his instructor, Dr. R. P. Hinshaw, who sponsored the article in the Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology.) In Johnson’s study of the Mattoon incident, he considers the victims as a group, and marvels that there are few children in his sample (after he rejects some because of parental influence.) Table 3 provides some demographic information.

Johnson shows that the majority of the victims were women of poor education and modest economic level, their ages peaking for the 20-29 group. No attacks were reported in the two high-income areas of Mattoon, and all the cases seem to have occurred within a uniform socio-economic group. As shown in Table 3, the demographic factors are quite at variance with those corresponding to the population of Mattoon at large, as indicated in the last column.

The unavoidable conclusion is that the characteristics of the victims was not random. What does this mean? One, selectivity by the perpetrator; or two, susceptibility of this age/socio-economic group, either toward psychogenic illness, or, more likely, greater credulity and thus a greater tendency to misinterpret the sights and sounds of the environment.

Let us go back now to the three possible hypotheses and attempt to arrive at a reasonable solution.

1. The Mass Hysteria Hypothesis

Johnson concludes that “the hypothesis of hysteria fits all of the evidence, without remainder” (p. 178). John- son’s facts, however, can be read in a different light. Although instances of MPI are rare, a pattern has emerged for the cases of hysterical contagion (another name used in the literature), defined by Kerchkoff and Bach (1968, p. 25) as follows:

A case of hysterical contagion is one in which a set of experiences or behaviors which are heavily laden with the emotion of fear of a mysterious force is disseminated through a collectivity. The type of behavior which forms the manifest content of the case may vary widely from one example to the next, but all are indicative of fear, and all are inexplicable in terms of the usual standards of mechanical, chemical or physiological causality.

Although the Mattoon incidents seem to satisfy this definition, one must emphasize that the best documented cases of MPI have occurred in enclosed spaces, such as workplaces or schools. The contagious behavior usually stems from a single case, or trigger event, and is characterized by a specific item, such as a bug bite or an odor. Some physical symptoms are considered typical, such as nausea, nervousness, weakness, and numbness. The number of incidents rapidly increases, reaches a maximum, and then tails off, the cycle terminating in a couple of weeks.

For the Mattoon case there was no event that could have triggered a mass hysteria. The three initial incidents — August 31 and September 1 — were real but had no immediate influence, as they were not publicized until September 2. Even then, and in spite of the sensationalist headlines and the extensive newspaper coverage, they failed to generate new cases until September 5. The word “first” in the column heading of the September 2 issue of the Mattoon Daily Journal-Gazette remains cryptic, and in fact, opens new possibilities.

The independently witnessed symptoms like vomiting and a great degree of excitation were unexplained, but how could they have happened if there were NO gasser to provide the stimulus? In addition, according to Johnson, only four of the victims were examined by physicians and diagnosed as suffering hysteria, hardly a significant percentage of total victims. The lack of cases on September 7 and 11 represents an anomaly, compounded by the fact that the graph shown in Johnson’s paper apparently peaks precisely on September 7, perhaps because he refers to telephone calls listed in the police blotter and not to verified incidents. As shown in Graph 1, the actual number of incidents peaked on September 10, and in spite of coverage by the newspaper until September 15, only one more case was reported (September 12).

The hysteria hypothesis not only fails to satisfy the evidence, but does not explain how people who did not know each other, apparently belonging to the same socio-economic and occupational level, and perhaps living in the same neighborhood, could come up with similar descriptions (as, for instance, in the cases prior to September 5).

All of this suggests the activity of unknown parties localized in a given area. Moreover, the victims were young females, all but one married, corroborating selectivity by the perpetrator very unlikely to occur with an imaginary gasser.

Of course, it may well be that initially, as supported by the evidence provided by the first cases, one or more unknown parties (the copycat is always a possibility), started to terrorize young women perhaps as a prank, but became scared when the community overreacted and the state police intervened.

The later cases were very likely caused by the media influence and no more than episodes prompted by the perceived presence of prowlers, which during the period were reported at the rate of 8–10 a week. (Thinking you saw a prowler when you are in a state of high anxiety or awareness that crimes have recently occurred in your neighborhood is not mass hysteria.) Johnson, however, vehemently insists on the psychogenic nature of the events: “The hypothesis of hysteria accounts for the rapid recovery of all victims and lack of after-effects… The objections to the hypothesis of hysteria come from the victims themselves” (pp. 177–178). Of course the victims recovered rapidly, as they had been only scared and and/or, at most, had inhaled some cooking gas. And naturally, they insisted on denying any hysteria suggestion as it was tantamount to calling them liars.

2. The Journalistic Scheme Hypothesis

The second hypothesis is daring but tenable. That word “first” in the September 2 issue cannot be lightly dismissed, and we must keep in mind that the press controlled the publicity given to the affair. It is quite possible that the original cases (which could have had a simple explanation, such as a gas leak) inspired a young reporter to make a name for himself with dramatic headlines and a front page report. The story was picked up by out-of-town newspapers, among others the Chicago Herald-American which according to Johnson, handled the story most thoroughly and most sensationally, and soon it was out of control. Perhaps after a while the editor of the paper became skeptical, but what could he really do, but backpedal and write “few real” in the September 11 headline, then change the tone toward the jocular on September 13, move the story to page six on September 15 and finally drop it altogether?

There is another factor in favor of this hypothesis: the lack of motivation. Nothing was stolen, the circumstances offered but limited gratification to a peeper, and even the victims did not have a reason to come forward with false claims. Yet our postulated ambitious newspaperman had everything to gain and nothing to lose. Could it have been the reporter, or a prankster set up by the newspaper? Short of a confession (and even confessions are problematic), we will probably never know for certain.

3. A Real Gasser

As we have already indicated, the first three cases (August 31 and September 1) definitely were real incidents, each one with two witnesses. Since they were not publicized until later, they could not have triggered the incidents that followed. Johnson argues for the suggestibility of young females of low education and social status. I am a physicist, not a psychologist. But even I can deduce that items not printed in the local newspaper certainly could not have influenced anyone.

The arguments advanced by Johnson on the nature of the gas are specious, to say the least, as are attempts to prove that since the characteristics of the alleged gas are impossible, so is the reality of the anesthetist. However, when the complaints of the victims and their symptoms are considered in some detail, it becomes very likely that the gas could have been regular cooking gas, accidentally or otherwise released in the rooms.

There are several indications of the presence of a real flesh and blood perpetrator, the most important being the statements of the initial witnesses. When Mr. B woke up sick in the middle of the night (August 31), he asked his wife if the gas had been left on. When Mr. A returned home about two hours after the alleged attack on Mrs. A, he says he saw a man run from the window. In the case of Mrs. C and her daughter (August 31), the daughter woke up coughing and when Mrs. C. got up to take care of her, she could hardly walk, a typical symptom of gas inhalation.

As previously discussed, the victims were not distributed randomly but belonged to a well-defined social group. This selectivity not only asserts the reality of the perpetrator, but, contrary to what Johnson tell us, provides a motive for his activities: gratification in scaring young females .

Johnson’s cavalier dismissal of the data supporting the real gasser explanation is a little surprising (p. 177):

The fact that vomiting did occur was authenticated in a few cases by outside testimony but, since vomiting could be produced by gas or hysteria or dietary indiscretions, this fact is not crucial. There is plenty of evidence from the police and other observers that the victims were emotionally upset by their experiences but this is not a crucial point. [Emphasis added.]

Not crucial? The fact that people reported seeing a prowler who might have been the anesthetist is also dismissed without further ado by Johnson, since prowlers were frequently reported in Mattoon. I agree, but how could anyone distinguish on sight between a regular prowler and a gasser? The plot of police calls presented by Johnson shows almost equal numbers for both events.

Conclusion: Applying Occam’s Razor

Johnson’s conclusion that the Mattoon affair was entirely psychogenic is unwarranted and not supported by the evidence. The idea of a journalistic scheme is attractive and has possibilities that should not be ruled out. It would be interesting to go back to Mattoon and dig through the archives of the Journal-Gazette to obtain further information about the reporter(s) covering the case. As for the third possibility — the existence of a real perpetrator — it follows from the details of the first three incidents, and perhaps could be corroborated by further study of the records. It is also clear that some of the later cases could have been prompted by the influence of the media, but I doubt that a true hysteria epidemic could have been turned off so suddenly. Such an abrupt termination, however, would be expected if we had a gasser who felt cornered by the police and decided it was safer to quit.

In a direct application of Occam’s Razor, I favor a combination of hypotheses 2 and 3: a flesh and blood gasser who was most likely a prankster whose motivations we will never know. Subsequently, the people of Mattoon were in a heightened state of awareness, seeing, hearing, and perhaps even smelling things that were not really there. This anxiety was driven by the media input, and subsequently killed by the media blank out.

Whatever the right causal combination is, the series of events in Mattoon, Illinois in the first two weeks of September, 1944, was most likely not a sequence of imaginary events triggered by another imaginary event, or even by a real one (made public only after some of the crucial cases had already occurred). If mass hysteria means what I think it means, and if there is such a phenomenon, the case of Mattoon is not a good example.

Bibliography

- Ballester Olmos, V.J. 1977. “Tienen Relacion los Avistamientos OVNIs con la Poblacion?” Stendek, 27: 31–39.

- Sandell, R. 1993. Magonia #46, June, p. 13.

- Shermer, M. B. 1994. “An Epidemic of Accusation: The Chaos of Witch Crazes and Their Modern Descendants.” Skeptic,Vol. 2, #3: 52–57.

- Stewart, J. R. 1977. “Cattle Mutilations: An Episode of Collective Delusion.” The Zetetic, Vol. 1, No.2, pp. 55–66.

- Swords, M. D. 1984. “Hysteria and UFOs — Is There a Connection?” MUFON UFO Journal, #196 to 198, July/Aug. to October.

- Johnson, D. M. 1945. “The ‘Phantom Anesthetist’ of Mattoon.” Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology,40: 175–86.

- Janet, P. 1901. The Mental State of Hystericals. New York: Putnam’s.

- Kerchkoff, A.C. and K.W. Bach. 1968. The June Bug: A Study of Hysterical Contagion. N.Y.

Skepticality

BANG! The Universe Verse

In keeping with Skepticality’s tradition of highlighting artists, illustrators, and filmmakers who bring great stories of science to their genres, this week’s episode welcomes James Lu Dunbar, author and illustrator of BANG! The Universe Verse. The first book in an educational series of graphic novels about the history of the universe, BANG! is crafted for children of all ages.

Swoopy chats with Jamie about the creative process for this series of self-published books — and explores how the second book in the series (It’s Alive, on the topic of evolution) is being funded by supporters via donations on Kickstarter.com.

MonsterTalk

Just Scratching the Surface

MonsterTalk frequently explores tales of imaginary monsters — creatures of myth, fiction, and folklore.

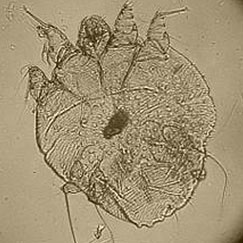

Today, the hosts consider a real creature, one that preys on humans and their closest animal companions. It is often invisible. It drinks blood to survive. And, it is responsible for many of the sightings of the dreaded chupacabra.

Podcast audiences may cringe and recoil in horror to learn the true facts of the creature known as — Sarcoptes scabiei!

NEW ON SKEPTICBLOG.ORG

Further Thoughts on the Ethics of Skepticism

In this week’s Skepticblog, Daniel Loxton continues the discussion from previous weeks about the ethical responsibility faced by skeptics when we speak out on medical matters, legal matters, or other matters of fact, whether from platforms as large as network television, or as small as a dinner party.