In this week’s eSkeptic:

The Earth Moves

Eppur si muove is Italian for “and yet it moves.” These are perhaps the most famous words attributed to the Italian physicist, mathematician, astronomer and philosopher Galileo Galilei. While this quote makes for a dramatic climax to the story of Galileo’s condemnation for heresy in 1633, there is no proof that the great scientist ever said it.

This week on Skepticality, Swoopy talks with author Dan Hofstadter, whose book The Earth Moves paints a unique picture not only of Galileo the heliocentrist, but also of Galileo the humanist.

In this week’s eSkeptic, we present the third in a series of classic historical pieces in skeptical and pseudoscience literature. Last week we presented William Jennings Bryan’s never-delivered Address to the Jury in the Scopes Case. A couple weeks before that, we republished Benjamin Franklin’s and Antoine Lavoisier’s investigation of Mesmerism for King Louis XVI of France. And, this week, we present Robert W. Wood’s famous letter that blew apart the chimerical search for n-rays, with an introduction by psychologist and skeptical investigator Terence Hines. A classic from skeptical history, this letter first appeared in Nature in 1904, republished here and in Skeptic magazine volume 4, number 4 in 1996.

What Ever Happened to n-Rays?

by Terence Hines

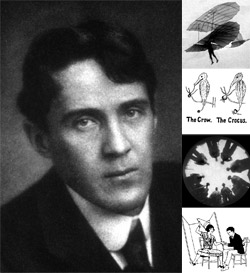

Robert Wood — justly renowned for fundamental discoveries in physical optics, and important contributions to astronomy, supersonics, and biophysics. See more notes at end of this article. (Click image to enlarge)

In early 1903, the news of the discovery of a new type of radiation in France spread through the international physics community. Rene Blondlot, one of the most famous physicists in the world, had made the discovery at the University of Nancy. He named the new radiation n-rays in honor of the university and city. The discovery of a new form of radiation was certainly not an unprecedented event at the start of the 20th century. Several other types of radiation had been reported in the dozen or so years previously (including x-rays). But none would be more controversial than n-rays.

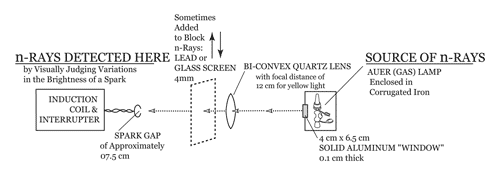

N-rays were supposedly a form of radiation exhibited by any number of substances, with the bizarre exceptions of green wood and “anesthetized” metal (metal soaked in ether or chloroform). Within less than a year of its announced “discovery,” no fewer than 30 papers were published confirming the existence of the new rays. Other laboratories, however, using more sophisticated methods were unable to replicate the findings. Blondlot’s measuring instrument was a spectroscope with an aluminum-coated prism and thread on the inside. The n-rays were refracted by the prism and spread out into a spectrum. The only way to see the normally invisible n-rays was to cause them to hit a treated thread (e.g., one coated in calcium sulfide). Moving the thread across the gap between the prism and n-ray source caused the thread to become illuminated and this is what was reported as a “detection” (see illustration below for another way to “detect” n-rays).

In 1903 Nature sent Johns Hopkins University physicist Robert W. Wood, who was attending a scientific conference in Britain, to Nancy, France, to investigate. During a series of experiments, when the lights were out, Wood secretly removed the prism from the spectroscope, after which n-rays were still detected, clearly an impossible result since the prism was supposedly critical for refracting the rays. In short, what Wood’s little experiment proved was that n-rays didn’t exist. Blondlot’s use of a purely subjective methodology, as opposed to an objective one, led him to believe in the reality of the new rays, as it did in several other laboratories, mostly in France. (There may have been some nationalistic bias here since the Germans had discovered x-rays).

Wood was an extraordinary individual whose wide-ranging areas of interest included many in physics, as well as non-traditional areas such as investigating spiritualistic mediums and the use of scientific methodology in crime detection. Following his visit to Blondlot’s laboratory, Wood reported his findings in the September 29, 1904, issue of Nature, then, as it is today, one of the leading scientific publications in the world. This letter, reprinted here, is a classic in skeptical literature. After its appearance in Nature, it was quickly published in French in the Revue Scientifique (Vol. 2, Oct. 22, 1904, pp. 536–538) and in German in the Physikalische Zeitschrift (Vol. 1, 1904, pp. 789–791).

The letter seems to have had quite an effect. According to M. Nye, whose excellent history of the n-ray affair should be consulted for further details (“N-rays: An Episode in the History and Psychology of Science.” Historical Studies in the Physical Sciences, 1980, 125–156), “only one confirming account of n-rays was presented to the [French] Academy” in the following years. Thus, Wood’s letter signaled the beginning of the end of the n-ray episode. The debate would simmer on for a few more years and Blondlot, who retired in 1909, continued his n-ray quest, but to no avail.

It is worth noting that nowhere in Wood’s letter did he specify at which laboratory it was that he made his observations. But everyone in the field knew.

The n-Rays

by Robert W. Wood

(Nature, September 29, 1904, 530–531)

The inability of a large number of skillful experimental physicists to obtain any evidence whatever of the existence of the n-rays, and the continued publication of papers announcing new and still more remarkable properties of the rays, prompted me to pay a visit to one of the laboratories in which the apparently peculiar conditions necessary for the manifestation of this most elusive form of radiation appear to exist. I went, I must confess, in a doubting frame of mind, but with the hope that I might be convinced of the reality of the phenomena, the accounts of which have been read with so much scepticism.

After spending three hours or more in witnessing various experiments, I am not only unable to report a single observation which appeared to indicate the existence of the rays, but left with a very firm conviction that the few experimenters who have obtained positive results have been in some way deluded.

A somewhat detailed report of the experiments which was shown to me, together with my own observations, may be of interest to the many physicists who have spent days and weeks in fruitless efforts to repeat the remarkable experiments which have been described in the scientific journals of the past year.

The first experiment which it was my privilege to witness was the supposed brightening of a small electric spark when the n-rays were concentrated on it by means of an aluminum lens. The spark was placed behind a small screen of ground glass to diffuse the light, the luminosity of which was supposed to change when the hand was interposed between the spark and the source of the n-rays.

It was claimed that this was most distinctly noticeable, yet I was unable to detect the slightest change. This was explained as due to a lack of sensitiveness of my eyes, and to test the matter I suggested that the attempt be made to announce the exact moments at which I introduced my hand into the path of the rays, by observing the screen. In no case was a correct answer given, the screen being announced as bright and dark in alternation when my hand was held motionless in the path of the rays, while the fluctuations observed when I moved my hand bore no relation whatever to its movements. I was shown a number of photographs which showed the brightening of the image, and a plate was exposed in my presence, but they were made, it seems to me, under conditions which admit of many sources of error. In the first place, the brilliancy of the spark fluctuates all the time by an amount which I estimated at 25 percent, which alone would make accurate work impossible.

Secondly, the two images (with n-rays and without) are built of “installment exposures” of five seconds each, the plate holder being shifted back and forth by hand every five seconds. It appears to me that it is quite possible that the difference in the brilliancy of the images is due to a cumulative favoring of the exposure of one of the images, which may be quite unconscious, but may be governed by the previous knowledge of the disposition of the apparatus. The claim is made that all accidents of this nature are made impossible by changing the conditions, i.e. by shifting the positions of the screens; but it must be remembered that the experimenter is aware of the change, and may be unconsciously influenced to hold the plate holder a fraction of a second longer on one side than on the other. I feel very sure that if a series of experiments were made jointly in this laboratory by the originator of the photographic experiments and Profs. Rubens and Lummer, whose failure to repeat them is well known, the source of the error would be found.

I was next shown the experiment of the deviation of the rays by an aluminum prism. The aluminum lens was removed, and a screen of wet cardboard furnished with a vertical slit about 3 mm. wide put in its place. In front of the slit stood the prism, which was supposed not only to bend the sheet of rays, but to spread it out into a spectrum. The positions of the deviated rays were located by a narrow vertical line of phosphorescent paint, perhaps 0.5 mm. wide, on a piece of dry cardboard, which was moved along by means of a small driving engine. It was claimed that a movement of the screw corresponding to a motion of less than 0.1 of a millimeter was sufficient to cause the phosphorescent line to change in luminosity when it was moved across the n-ray spectrum, and this with a slit 2 or 3 mm. wide. I expressed surprise that a ray bundle 3 mm. in width could be split up into a spectrum with maxima and minima less than 0.1 of a millimeter apart, and was told that this was one of the inexplicable and astonishing properties of the rays. I was unable to see any change whatever in the brilliancy of the phosphorescent line as I moved it along, and I subsequently found that the removal of the prism (we were in a dark room) did not seem to interfere in any way with the location of the maxima and minima in the deviated (!) ray bundle.

I then suggested that an attempt be made to determine by means of the phosphorescent screen whether I had placed the prism with its refracting edge to the right or the left, but neither the experimenter nor his assistant determined the position correctly in a single case (three trials were made). This failure was attributed to fatigue.

I was next shown an experiment of a different nature. A small screen on which a number of circles had been painted with luminous paint was placed on the table in the dark room. The approach of a large steel file was supposed to alter the appearance of the spots, causing them to appear more distinct and less nebulous. I could see no change myself, though the phenomenon was described as open to no question, the change being very marked. Holding the file behind my back, I moved my arm slightly towards and away from the screen. The same changes were described by my colleague. A clock face in a dimly lighted room was believed to become much more distinct and brighter when the file was held before the eyes, owing to some peculiar effect which the rays emitted by the file exerted on the retina. I was unable to see the slightest change, though my colleague said that he could see the hands distinctly when he held the file near his eyes, while they were quite invisible when the file was removed. The room was dimly lit by a gas jet turned down low, which made blank experiments impossible. My colleague could see the change just as well when I held the file before his face, and the substitution of a piece of wood of the same size and shape as the file in no way interfered with the experiment. The substitution was of course unknown to the observer.

I am obliged to confess that I left the laboratory with a distinct feeling of depression, not only having failed to see a single experiment of a convincing nature, but with the almost certain conviction that all the changes in the luminosity or distinctness of sparks and phosphorescent screens (which furnish the only evidence of n-rays) are purely imaginary. It seems strange that after a year’s work on the subject not a single experiment has been devised which can in any way convince a critical observer that the rays exist at all. To be sure the photographs are offered as an objective proof of the effect of the rays upon the luminosity of the spark. The spark, however, varies greatly in intensity from moment to moment, and the manner in which the exposures are made appears to me to be especially favourable to the introduction of errors in the total time of exposure which each image receives. I am unwilling also to believe that a change of intensity which the average eye cannot detect when the n-rays are flashed “on” and “off” will be brought out as distinctly in photographs as is the case on the plates exhibited.

Experiments could easily be devised which would settle the matter beyond all doubt; for example, the following: Let two screens be prepared, one composed of two sheets of thin aluminum with a few sheets of wet paper between, the whole hermetically sealed with wax along the edges. The other screen to be exactly the same, containing, however, dry paper.

Let a dozen or more photographs be taken with the two screens, the person exposing the plates being ignorant of which screen was used in each case. One of the screens being opaque to n-rays, the other transparent, the resulting photographs would tell the story. Two observers would be required, one to change the screens and keep a record of the one used in each case, the other to expose the plates.

The same screen should be used for two or three successive exposures, in one or more cases, and it should be made impossible for the person exposing the plates to know in any way whether a change had been made or not.

I feel very sure that a day spent on some such experiment as this would show that variations in the density on the photographic plate had no connection with the screen used.

Why cannot the experimenters who obtain results with n-rays and those who do not try a series of experiments together, as was done only last year by Cremieu and Pender, when doubt had been expressed about the reality of the Rowland effect?

Readers interested in more information on Wood himself should consult his biography Doctor Wood: Modern Wizard of the Laboratory by William Seabrook, published in 1941.

The 4 small illustrations to the right of Wood’s portrait at the beginning of this article represent a few of Wood’s wide ranging pursuits: (top to bottom) 1) Wood participated in many experiments in early aviation and took this photo in 1896 of aviation pioneer Otto Lilienthal’s last successful flight. Wood is said to have tried the glider himself. 2) He wrote a best-selling book How to tell the Birds from the Flowers that lampooned contemporary nature books. 3) He invented and named the fish-eye camera, as well as pioneering many other photographic techniques such as infrared and ultraviolet photography. 4) Wood also found time to investigate leading psychics of his day, including Margery (pictured), and Eusapia Palladino.

NEW ON MICHAELSHERMER.COM

Can You Hear Me Now?

Reports of a link between cell phones and cancer have periodically surfaced ever since cell phones became common appendages to people’s heads in the 1990s. In Michael Shermer’s October Scientific American column, he discusses how physics shows that it is virtually impossible for cell phones to cause cancer.

NEW ON SKEPTICBLOG.ORG

Touching History

On Sunday, October 3, a group of skeptics gathered in Falls Church, Virginia to celebrate James Randi’s 82nd birthday. Randi was joined by paranormal investigator Joe Nickell, Center for Inquiry founder Paul Kurtz, psychologist and magician Ray Hyman, magician Jamy Ian Swiss, JREF president D.J. Grothe, evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, and many other skeptical luminaries from around the world.

Michael Shermer had the opportunity to explore a private collection of some of the rarest books in the history of science, owned by a good friend of James Randi. Shermer shares that experience in this week’s Skepticblog post.