In this week’s eSkeptic:

- Available Digitally Now: Skeptic magazine 17.4: Alternative Cancer Cures

- Next Geology Tour: Death Valley Redux (January 19–21, 2013)

- Next Lecture at Caltech: Dr. Donald Yeomans on Near-Earth Objects

- Skepticality: Interview with Penn Jillette

- Feature Article: The Evolution of Evolution (three book reviews)

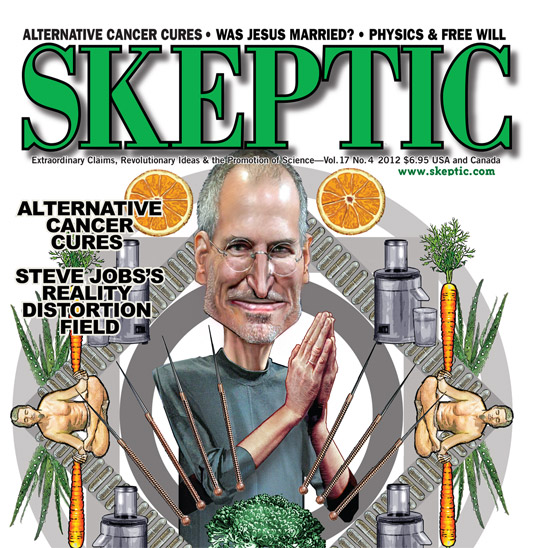

Skeptic magazine 17.4

Alternative Cancer Cures

Available digitally now and for pre-order at Shop Skeptic. This is will be on newsstands soon, but is not available yet.

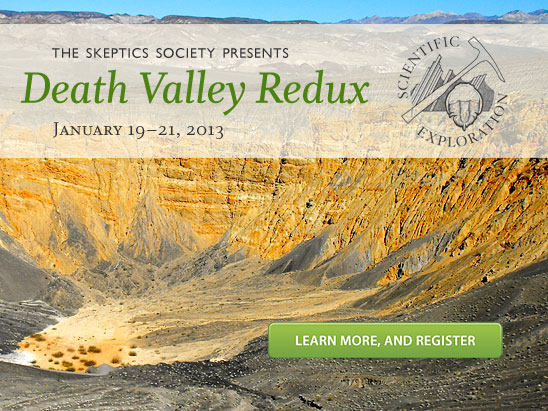

Join Us on our Next Geology Tour:

Death Valley Redux (January 19–21, 2013)

JOIN THE SKEPTICS SOCIETY for a fun three-day trip from Las Vegas to Death Valley to Red Rock Canyon this coming MLK weekend! Due to demand, we will reprise part of our popular Death Valley trip, but reverse the direction and go to some new stops. We will focus on the north half of Death Valley this time, with stops at Scotty’s Castle, Ubehebe Crater, and Rhyolite ghost town in Nevada. We will also revisit our popular stop at Calico ghost town, visit the gigantic Kelso Dunes, and on the way home see Pinnacles National Natural Landmark and Red Rock Canyon. We will be staying at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas on the first night, and the Marriott Springhill Suites in Ridgecrest on our second night. Come join us and see some of the most amazing scenery in the world!

Ubehebe Crater (above) is in a volcanic crater field located in the North end of Death Valley. (Photo by Gingi Yee)

Click an image to enlarge it.

What’s Included?

Tour package includes charter bus, hotels, breakfast, lunch, snacks, lectures, museums, park fees, and a guide booklet. Your trip fee also includes a $150 tax deductible donation to the Skeptics Society. Seats are limited, so make your reservations soon!

Questions?

Email us or call 1-626-794-3119 with a credit card to secure your spot.

Sign up now—seats are going fast!

Only 24 out of 56 seats left.

Watch Dr. Donald Yeomans for free online,

broadcast live from Caltech!

New Admission Policy and Prices

Please note there are important policy and pricing changes for this season of lectures at Caltech. Please review these changes now.

SINCE 1992, the Skeptics Society has sponsored the Skeptics Distinguished Science Lecture Series at Caltech: a monthly lecture series at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, CA. Most lectures are available for purchase in audio & video formats. Watch several of our lectures for free online. Our next lecture is…

Near-Earth Objects: Finding Them Before They Find Us

Sunday, December 2, 2012 at 2 pm

Baxter Lecture Hall

Of all the natural disasters that could befall us, only an Earth impact by a large comet or asteroid has the potential to end civilization in a single blow. Yet these near-Earth objects also offer tantalizing clues to our solar system’s origin, and someday could even serve as stepping-stones for space exploration. In this book, Donald Yeomans introduces readers to the science of near-Earth objects—its history, applications, and ongoing quest to find near-Earth objects before they find us. Yeomans takes readers behind the scenes of today’s efforts to find, track, and study near-Earth objects. He shows how the same comets and asteroids most likely to collide with us could also be mined for precious natural resources like water and oxygen, and used as watering holes and fueling stations for expeditions to Mars and the outermost reaches of our solar system.

Followed by…

- DR. PAUL ZAK

The Moral Molecule: The Source of Love and Prosperity

Sunday, December 16, 2012 at 2 pm

Baxter Lecture Hall

Interview with Penn Jillette

SKEPTICALITY EPISODE 196

This week on Skepticality, Derek spends some time with Penn Jillette discussing his journey into magic, his past with James Randi, where we might see Penn & Teller next, and his latest book, Every Day is an Atheist Holiday! More Magical Tales from the Author of God, No!.

Get the Skepticality Podcast App

for Apple and Android Devices!

Get the Skepticality App — the Official Podcast App of Skeptic Magazine and the Skeptics Society, so you can enjoy your science fix and engaging interviews on the go! Available for Android, iPhone, iPad, and iPod Touch. Skepticality was the 2007 Parsec Award winner for Best “Speculative Fiction News” Podcast.

About this week’s eSkeptic

In this week’s eSkeptic, Jason Rosenhouse reviews three books: Darwin’s Ghosts: The Secret History of Evolution, by Rebecca Stott (Spiegel and Grau, 2012, ISBN 978-1400069378); American Genesis: The Evolution Controversies From Scopes to Creation Science, by Jeffrey P. Moran (Oxford University Press, 2012, ISBN 978-0195183498); and Darwin the Writer, by George Levine (Oxford University Press, 2011, ISBN 978-0199608430).

Jason Rosenhouse is an associate professor of mathematics at James Madison University in Harrisonburg , VA. He is the author most recently of Among the Creationists: Dispatches From the Anti-Evolutionist Front Line (Oxford University Press), a memoir recounting his experiences socializing with creationists. He regularly discusses science, religion, politics and chess at ScienceBlogs EvolutionBlog, as part of the National Geographic Blog Network.

The Evolution of Evolution

book reviews by Jason Rosenhouse

A while back I decided to plug a hole in my literary education by reading Charles Dickens’s novel Martin Chuzzlewit, first serialized in 1843 and 1844. Near the end of the first chapter, in which Dickens relates the sometimes sordid history of the Chuzzlewit family, I came to this:

At present it contents itself with remarking, in a general way, on this head: Firstly, that it may be safely asserted, and yet without implying any direct participation in the Manboddo doctrine touching the probability of the human race having once been monkeys, that men do play very strange and extraordinary tricks.

Though I had for some years taken a semi-professional interest in evolutionary biology, the name of Manboddo was new to me. Certainly I was aware that the notion of common descent among species, including the shared ancestry of humans with apes, long predated Charles Darwin. Still, despite having read several histories of evolutionary thinking in biology, no one had mentioned Manboddo. A few moments with Google revealed that he was a Scottish judge who, while better known for his contributions to linguistics, speculated about the possibility of evolution by natural selection.

You can therefore imagine my slight disappointment when I discovered that Rebecca Stott, a professor of English literature at the University of East Anglia, chose not to discuss Manboddo in her own history of evolutionary thought, Darwin’s Ghosts: The Secret History of Evolution. But that is my only criticism of this excellent book, which paints vivid portraits of some of Darwin’s most notable predecessors.

Upon publishing On the Origin of Species, Darwin knew to expect criticism both from religious authorities and from a hidebound scientific establishment. He was especially stung, however, by a charge leveled by the Reverend Baden Powell, then a mathematician at Oxford. Powell was generally supportive of Darwin’s views, but he was very critical of Darwin’s failure to recognize the long history of the evolutionary hypothesis. Darwin rectified this by including an historical essay in later editions of On the Origin of Species.

Stott’s history begins with proto-evolutionary thinkers such as Aristotle, the 8th century Muslim writer Jahiz, and Leonardo Da Vinci, and eventually concludes with Erasmus Darwin (grandfather of Charles), Jean Baptiste de Lamarck, Robert Chambers, and Alfred Russell Wallace. Common to all of these thinkers was the realization that nature defies most attempts at drawing sharp lines of demarcation. Even fundamental distinctions between plant and animal become murky when you consider critters such as sea sponges and polyps. The concept of “homology,” by which we mean the appearance of the same anatomical structures across widely different species (the similar arrangement of bones in the forelimbs of humans, bats, birds and whales being a classic example), was known already to Aristotle. Careful study of nature reveals only continuity and smooth gradations, precisely as we would expect in an evolutionary world.

A second recurring theme is the lengths to which our heroes frequently went to avoid running afoul of religious authorities. Since evolutionary thinking has been heretical in most times and places, scientists pursuing such investigations were forced to be circumspect in expressing their views. Leonardo De Vinci famously practiced mirror writing, to make it more difficult for prying eyes to discern his ideas. Denis Diderot, endlessly suspected of heresy, learned to be vague and slippery in his prose. Consider this paragraph, from Diderot’s work Thoughts on the Interpretation of Nature (as quoted by Stott):

May it not be that, just as an individual organism in the animal or vegetable kingdom comes into being, grows, reaches maturity, perishes and disappears from view, so whole species may pass through similar stages? If the faith had not taught us that the animals came from the hands of the Creator just as they are now, and if it were permissible to have the least uncertainty about their beginning and their end, might not the philosopher, left to his own conjectures, suspect that the animal world has from eternity had its separate elements confusedly scattered through the mass of matter, that it finally came about that these elements united—simply because it was possible for them to unite…that millions of years have elapsed between each of these developments; that there are perhaps still new developments to take place which are as yet unknown to us…and that [man] will finally disappear from nature, forever, or rather, will continue to exist but in a form and with faculties wholly unlike those which characterize him in this moment of time? But religion spares us many wanderings and much labour. If it had not enlightened us on the origin of the world and the universal system of beings, how many different hypotheses would we not have been tempted to take for nature’s secret?

Just imagine that you are the poor inquisitor charged with finding something explicitly heretical in that.

II

Today the situation has reversed. Evolution is now the foundation for all research in the life sciences. We need a word stronger than “heresy” to describe notions of species fixity or created kinds. Scientists might bicker among themselves regarding the fine points of the theory, but outright anti-evolutionism is now the exclusive province of the less enlightened forms of religion.

Which is not to say anti-evolutionism is no longer a potent social force. Public opinion polling in the United States consistently shows that close to half the population is antipathetic towards Darwin, and hostilities are almost certain to ensue in any school district that tries to teach biology honestly. It has been this way ever since evolution began working its way into popular culture and school curricula, roughly around the turn of the 19th to the 20th century.

The history of American anti-evolutionism has been told so many times you might think there is nothing left to say. Happily, Jeffrey Moran, an historian at the University of Kansas, has managed to find some largely-unexplored angles. His book American Genesis: The Evolution Controversies From Scopes to Creation Science, focuses especially on the under-appreciated role of women and minorities in the anti-evolution movement.

If you have ever discussed this topic with anti-evolutionists, you know that the dispute is only tangentially about the origin of species. Nor is it primarily about idiosyncratic interpretations of the Bible. Rather, the problem is that evolution is seen as a proxy for loose moral standards and a rejection of God’s will. “By sapping popular belief in the truth of the Bible,” writes Moran, describing the attitudes of activists in the 1920s, “[evolution] threatened the only reliable foundation of morality, while reducing humans to the level of amoral animals. No wonder sexual morality was receding at the same time as Darwinism was flooding the nation” (39).

In these early days of the movement, women took an especially prominent role. Evolution was being taught to schoolchildren, thereby usurping, it was believed, a mother’s authority to tend to the moral development of her child. For this reason, much of the early rhetoric in anti-evolutionism centered on images of motherhood. It is a brave politician who could stand against that. Referring to Tennessee’s Butler Act, the law at the center of the Scopes trial, Moran writes, “Always the specter of their political power loomed in the background. Many of the legislators, and certainly [Tennessee] Governor Austin Peay, were privately tepid toward the Butler Act, but they were more uneasy about what outright opposition might do to their political careers” (41).

This history may come as a surprise to those steeped in the modern form of the controversy. Women have all but vanished from the anti-evolution movement, a trend Moran traces to the increased emphasis on science in the rhetoric of anti-evolutionism. He writes,

Further, women as symbols have largely faded from the public rhetoric of antievolution. This change began in the 1960s with the rise of scientific creationism and has reached its apogee in the intelligent design movement. Despite the contributions of [activists Nell] Segraves and [Jean] Sumrall, as creationists increasingly portrayed their movement as challenging evolution on purely scientific grounds, they were no longer as free to employ the powerful imagery of motherhood and children, at least in public or legal settings. Where once the antievolutionists waved the flag of “country, God, and mother’s song,” their modern heirs present disquisitions on flood geology and the wily flagellum. (46)

Especially interesting in the history of American anti-evolutionism is the way in which evolution exacerbated tensions within communities. The divide between North and South only grew, as the former tended to see acceptance of evolution as a sign of scientific enlightenment while the latter preferred to defend traditional Christianity. Even more powerful was the divide in the African American community. Secular intellectuals such as W. E. B. DuBois approved of evolution’s emphasis on the unity of human origins. They were countered by many Black preachers, who saw in evolution’s threat to the Bible’s credibility an equally grave threat to the foundations of the Black community. Moreover, having frequently been likened to apes in racist literature, they were not keen on a theory that could so easily be twisted to portray them as less evolved than other races. It is interesting that in taking so strong a stand against evolution, these preachers were aligning themselves with a popular strain of racist thought among Southern Whites. In his classic work The Mind of the South, journalist W. J. Cash writes, “One of the most stressed notions which went around was that evolution made a Negro as good as a white man—that is, threatened White Supremacy.” It is difficult to read Moran’s book without feeling great sadness for its protagonists. It is hard to fault the intentions of the anti-evolutionists. After all, they are trying to protect their children’s morality in a world that has completely left their views behind. But this sympathy must be tempered with the realization that they are simply wrong about everything related to evolution, both with respect to its scientific merits and to the consequences of accepting it as true. Blind adherence to tradition is never admirable, and the ambitions of the anti-evolutionists must be fought by anyone who cares about the continued health of society.

III

It is amusing to juxtapose Stott’s book with Moran’s. The result is a nearly continuous narrative that opens with the earliest speculations about evolution, builds up to a critical mass with a glut of thinkers endorsing the idea just prior to the publication of On the Origin of Species, and then emerges on the other side with the forces of religion and tradition wondering what hit them.

The gap in the story is Darwin himself. Why did he succeed where so many before had failed? In part the explanation lies in the depth of his scholarship relative to his predecessors. He simply presented a better case than anyone who came before. The wealth of facts he presented, based both on an encyclopedic knowledge of contemporary scientific work and on his own meticulous investigations, really did make common descent seem obvious.

Surely, though, that is not the whole story. Something more than a strong case is required to move people away from an entrenched orthodoxy. Darwin famously described On the Origin of Species as “one long argument,” and as such he needed to make use of the lawyerly skills of persuasion as much as his acumen as a scientist.

George Levine, emeritus professor of English at Rutgers University, does not mince words in making this point in his new book Darwin the Writer. Here’s his opening paragraph:

If one were to try to identify the most important book in English literature written in the nineteenth century, it wouldn’t be a novel of Dickens, neither David Copperfield nor Bleak House. It wouldn’t be what is probably the greatest English novel of the nineteenth century, George Eliot’s Middlemarch. Nor would it be Wordsworth’s great poem, “The Prelude.” It wouldn’t be “literature” in the conventional sense, at all. Rather, it would be Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, published on November 24, 1859. (1)

And skipping ahead just a bit:

It is On the Origin of Species that significantly changed the way everyone, not only the great writers of the time, could look at the world. And although it is normally and correctly assumed that that’s because the idea was so powerful, I believe that much of its great influence followed from its art, that is, from the particular way that Darwin found to make his case, the particular way the book was written. (2)

There is a small industry of books discussing Darwin from the standpoint of literary theory, but Levine’s is one of the most interesting and accessible. His chapter emphasizing Darwin’s use of paradox is especially insightful. Levine writes,

From this perspective, we can see even more clearly why Darwin’s entire theory and all of its details, however soberly registered, amount to a giant paradox. Consider the conditions of Darwin’s world. What is stable is in motion; what is enormous depends on minutiae; what seems peaceful is at war; struggle is often mutual dependency; lowly worms create the large green expanses of England; six thousand years is no time at all; “species” is an arbitrary term, not really much different from “variety”; if unchecked by natural selection, even slow-breeding elephants would entirely cover the earth within five centuries; there are woodpeckers living where not a tree grows; there are web-footed birds that never go near the water; we are related physiologically to all living things, not only apes but barnacles and spiders. … The world of brilliant adaptation is moved not by a creative intelligence but by “unknown laws of nature,” and in nature itself the only intelligence is that of organisms, and most obviously and particularly humans. In early chapters I have offered yet more examples to show that this breathtaking litany could go on. (127)

Levine is also persuasive in contrasting modern presentations of evolution, in which natural selection is often analogized to a machine or an algorithm, with Darwin’s own language analogizing it to an intelligent craftsman. No doubt the shift in emphasis is largely the result of the different cultural concerns faced by Darwin as compared with modern writers. Whereas Darwin was trying to ease his readers away from an overtly religious way of looking at the origin of species, modern writers are addressing audiences well-accustomed to the idea of seeking natural explanations for natural phenomenon.

Some of Levine’s material will not mean much to those not steeped in the history of English literature. That notwithstanding, your reading of Darwin will be enriched for considering his observations.

IV

In seeking to explain the causes of some momentous historical transition, you will never go wrong attributing it to the subtle and complex influence of many social and cultural factors. On the other hand, Whig approaches to history, in which we see the past as an inexorable march of progress and enlightenment leading to a glorious present, are nearly always oversimplifications.

These are important lessons, but we should not let them blind us to instances where history really does present us with clear, unambiguous themes. How can you not understand the evolution of evolution except as a steady march of progress, from tentative, fearful beginnings, through the watershed of Darwin’s work, to the idea’s modern triumph? Why should I not take some pride in the gradual weakening of dogmatic, religious ways of understanding nature in favor of the infinitely more useful scientific approach?

In the end, the story as it reveals itself in the work of Stott, Levine and Moran seems to bear out the wise words of Isaac Asimov, “[A worldview] that is patently in error cannot change the universe to conform to itself. However popular it may be and however irritatingly it may survive refutation, its falseness condemns it—in the end—to nothingness.” It has taken many centuries, and creationism remains dangerous even in its death throes, but its falseness has, indeed, consigned it to nothingness. That is quite properly viewed as the happy ending to a long story, complete with heroes and villains. Perhaps that view is Whiggish and simplistic, but it is no less true for that. ![]()