In this week’s eSkeptic:

- $1.99 Digital Back Issues: Now thru July 19th in the Skeptic Magazine App

- Skepticality Episode 210: Talkin’ Death and Injury

- 30 Day Free Trial: on digital subscriptions for iOS devices (4 issues, $14.99)

- Feature Article: A Room with a Conspiratorial View

- The Amazing Meeting 2013: July 11–14, South Point Casino, Las Vegas

Digital Back Issues of Skeptic Magazine

ON SALE NOW THRU JULY 19

Enjoy huge savings on over 40 of Skeptic magazine’s most popular back issues in digital format! Download them ON SALE NOW THRU July 19, 2013 for $1.99 each within the Skeptic Magazine App for iOS, Android, BlackBerry PlayBook, Kindle Fire HD, Mac, PC, and Windows 8 devices.

For other devices and

more information, visit skeptic.com/magazine/app

Talkin’ Death and Injury

SKEPTICALITY EPISODE 210

This week on Skepticality, Derek has a discussion with Geoffrey “Thor” Desmoulin, a Biomedical Engineer from Vancouver, Canada. Geoffrey works in accident reconstruction and medical device testing. Most people, however, know him best from his well-loved Spike TV show Deadliest Warrior. Using scientific testing and a bit of investigation, the show featured highly detailed dramatizations of historical combat scenarios to find answers to questions like: ‘Who would win in a toe to toe fight, a Ninja or a Spartan?’ It’s kind of like Mythbusters, but more dangerous.

Get the Skepticality App

Get the Skepticality App — the Official Podcast App of Skeptic Magazine and the Skeptics Society, so you can enjoy your science fix and engaging interviews on the go! Available for Android, iPhone, iPad, and iPod Touch. Skepticality was the 2007 Parsec Award winner for Best “Speculative Fiction News” Podcast.

30 DAY FREE TRIAL

on New Digital Subscriptions

to Skeptic Magazine

Download the free Skeptic Magazine App on your iOS devices and enjoy a 30 day FREE TRIAL on a new digital subscription to Skeptic magazine (1 year/4 issues for $14.99).

About this week’s eSkeptic

For some obsessed fans of Stanley Kubrick’s 1980 film, The Shining, there exists hidden meaning in the film. Are these fans suffering from confirmation bias, or did Stanley Kubrick intend to leave clues, like a riddle to be solved? In this week’s eSkeptic, Will Dowd conspiracy thinking in this review of Room 237, a documentary directed by Rodney Ascher, produced by Tim Kirk, and distributed by IFC Films (released January, 2012, 102 minutes).

Will Dowd is a freelance writer based in Boston. He has received an M.S. in Science Writing from MIT and an M.F.A. in Creative Writing from New York University.

A Room with a Conspiratorial View

by Will Dowd

Since its theatrical release in 1980, Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining has attracted an unusual cult following. A small number of obsessed fans believe the film, adapted from the Stephen King bestseller, is rife with hidden meanings. These fans and their far-out theories are the subject of Room 237, a documentary directed and edited by Rodney Ascher.

In Room 237 five fans present their theories in voice-overs played on top of scenes from The Shining. While they have radically different interpretations of the movie, they all agree on one thing: The Shining is not what it seems. It only appears to be the story of Jack Torrance, the winter caretaker of a creepy hotel, who attempts to murder his wife Wendy and son Danny. Beneath the surface, they opine, the movie is about something else entirely.

According to one of these talking heads, journalist Bill Blakemore, The Shining is really about the genocide of the American Indians—a theory based largely on the hotel’s Native American decorative motifs and the cans of Calumet baking powder on the storeroom shelves. History professor Geoffrey Cocks, on the other hand, sees The Shining as an allegorical exploration of the Holocaust. His suspicions were first raised by the German brand of Jack’s typewriter.

The most outlandish theory belongs to Jay Weidner, who believes that Stanley Kubrick was recruited by NASA to fake the Apollo moon landing footage. According to Weidner, The Shining is Kubrick’s coded confession. He builds his case on details like Danny’s sweater, which depicts an Apollo rocket, and the fact that Kubrick changed the number of the haunted hotel room from the novel’s 217 to the film’s 237. (The moon is roughly 237,000 miles from Earth.) In Weidner’s eyes, the iconic scene in which Wendy discovers Jack’s unhinged manuscript (“All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy”) reflects an actual event—Christiane Kubrick’s discovery of her husband’s secret deal with the U.S. government. It is worth mentioning that Christiane appeared in Dark Side of the Moon, a 2002 mockumentary that lampooned the Kubrick moon landing theory. Clearly the mockumentary failed to dissuade believers.

In fact, none of the theories proposed in Room 237 are convincing. Leon Vitali was Kubrick’s personal assistant during the filming of The Shining. In a recent interview with The New York Times, he dismissed the theories as “balderdash.” According to Vitali, Kubrick chose the Calumet cans because they had bright colors, the Apollo sweater because it was handmade and available, and the Adler typewriter—Stanley’s own, it turns out—because it was practical and looked good on the oak table. The background details are not clues left by Kubrick, Vitali insists, but products of on-set improvisation and pragmatism.

Despite the absurdity of the claims, however, Room 237 is a compelling film for skeptics because it works as a brilliant case study in confirmation bias. Though they arrive at different conclusions, the theorists all report the same sequence of events. Each experienced a eureka moment, formed a hypothesis, then watched The Shining over and over again to gather supporting evidence. We learn enough about their background to understand why they see what they see. For example, Bill Blakemore, who alleges the American Indian subtext, grew up near the Calumet harbor and spent his childhood summers collecting Native American pottery.

To varying degrees, the theorists are aware of their biases. “I began to see the number forty two appear in the film,” Geoffrey Cocks says, “and, for a German historian, if you put the number forty two and a German typewriter together, you get the Holocaust.” But this self-awareness does not make them question their conclusions. Instead they see themselves as uniquely suited to spot Kubrick’s secret intention.

Jay Weidner recalls watching The Shining explicitly to find clues of Kubrick’s involvement in faking the moon landing footage. “I wasn’t sure I was right for the first hour,” he says. “I wasn’t sure if I was blurring the line between what I wanted to see and what I was seeing.” But once he noticed Danny’s Apollo sweater, he knew he was right. “Every line began ringing true,” he says.

By juxtaposing several incompatible interpretations of the same film, Room 237 displays the power of confirmation bias. It also shows the ridiculous places it can lead. At one point, Weidner claims to see Kubrick’s face airbrushed onto a cloud in the opening credits. I tried, but I couldn’t see it.

The most compelling question that Room 237 raises is why The Shining. What is it about this particular film that invites such fanatical scrutiny and wild speculation? Kubrick’s personality is partly to blame. His notorious mania for detail, along with his reputation for filming countless takes, has given fans license to attach significance to minutiae. The theorists of Room 237 scrutinize every inch of the frame for clues. Also, Kubrick refused on principle to explain his films, leaving them open for interpretation. As he said in an interview about 2001: A Space Odyssey: “You’re free to speculate as you wish about the philosophical and allegorical meaning of the film—and such speculation is one indication that it has succeeded in gripping the audience at a deep level.”

But the main reason The Shining inspires conspiracy thinking, I believe, is Kubrick’s signature artistic choice to leave out a key piece of explanation from the narrative. Kubrick was a serial adapter of literature—all but two of his films are based on novels or short stories. In the process of adaptation, he frequently excised vital information from the source material. In 2001: A Space Odyssey, for example, the computer HAL tries to kill the crew of Discovery One. In the Arthur C. Clarke novel, HAL’s breakdown is explained—it’s been forced to lie about the mission—whereas in the film, HAL’s motivation is a complete mystery.

Shakespeare, himself a prolific adapter, used the same technique. Why does Hamlet feign madness? Why does Iago hate Othello? Why does Lear stage a love test for his three daughters? Again and again, Shakespeare broke with his source material and left a central question blank. In Will in the World, scholar Stephen Greenblatt explains: “Shakespeare found that he could immeasurably deepen the effect of his plays, that he could provoke in the audience and in himself a peculiarly passionate intensity of response, if he took out a key explanatory element, thereby occluding the rationale, motivation, or ethical principle that accounted for the action that was to unfold. The principle was not the making of a riddle to be solved, but the creation of a strategic opacity.” By inserting a black hole at the center of his tragedies, Shakespeare made them unresolvable, and therefore endlessly playable.

In the same way, The Shining does not fully make sense. Why does Jack try to murder his family? Is he insane? Is he possessed? Unlike the Stephen King novel, the film never provides a definitive answer. Its narrative does not add up. As a result, we cannot file away the profoundly disturbing images. They linger in the mind. They haunt. This, of course, was Kubrick’s true intention.

The theorists of Room 237 turn The Shining into a code, an allegory, a riddle to be solved. They attempt to impose a rational scheme on an irrational story. While they are deeply engaged with The Shining, they are also resisting the film and its dreamlike spell. By the end of the documentary, their theories seem like elaborate efforts to tame the horror, to make sense of the nightmare, to wake up. ![]()

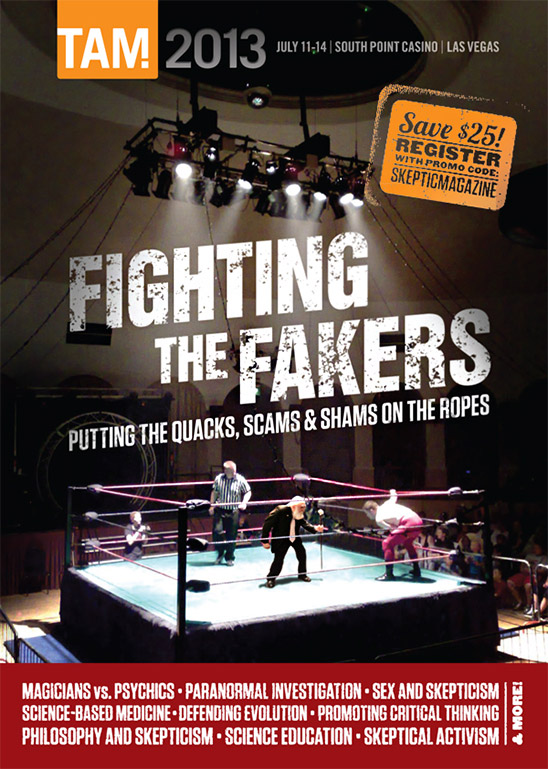

The Amazing Meeting 2013

South Point Casino, Las Vegas

July 11–14, 2013

Once again the Skeptics Society is proud to be a sponsor of the greatest skeptical gathering in the galaxy…The Amazing Meeting (TAM), featuring a stellar line up of speakers including: Susan Jacoby, Dan Ariely, Susan Blackmore, Jerry Coyne, Susan Haack, Marty Klein, Cara Santa Maria, Steven Novella, the Amazing One himself, James Randi, and around 50 others! Learn more and register online now…