Order the hardcover from Shop Skeptic

Order the hardcover from Amazon

Order the Amazon Kindle Edition

Order the audiobook from Amazon

Order the audiobook from iTunes

The year 1815 was an important one in history. On January 8, the Battle of New Orleans ended the War of 1812—even though it was fought AFTER the treaty ending the war had already been signed in 1814. (Communications across the Atlantic were very slow in those days.) In February, Napoleon Bonaparte escaped from exile on the isle of Elba, raised another huge French army, took control of France, and ruled for 100 days. Then he was defeated at the Battle of Waterloo on June 18, and ended up in his final place of exile on the remote Atlantic island of Saint Helena, where he passed the remainder of his days. Soon the French throne returned to the royal family with the rule of Louis XVIII. Less known at the time was the publication of the first geologic map by the humble canal engineer, William Smith, which has been called “the map that changed the world.”

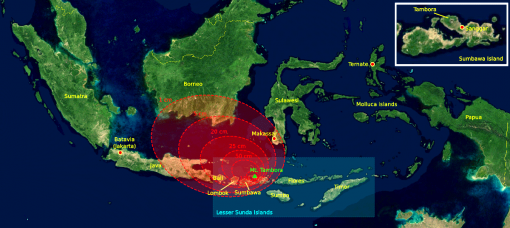

April 10 was also the 200th anniversary of a momentous event in geology, and in human affairs: the eruption of Mount Tambora. It is the largest volcanic eruption in recorded human history, much bigger than the enormous eruption of Mt. Krakatau in 1883, or the much smaller eruptions of Mt. Saint Helens in 1980 or Mt. Vesuvius in 71 A.D. Mt. Tambora is on the island of Sumbawa, in the Indonesian Archipelago, east of Java. Indonesia is home to hundreds of active volcanoes. (Krakatau is west of Java, in the Sunda Strait between Java and Sumatra). There was an even larger eruption of Mt. Toba in northern Sumatra 71,000 years ago, which nearly wiped out humans on this planet, but there are no historical records of this ancient event.

When Tambora erupted in 1815, it was heard on Sumatra, over 2000 km (1200 miles) away, and heavy ash falls covered most of Indonesia. The Tambora eruption killed between 70,000-90,000 people, of whom 12,000 were killed directly by the eruption, and the rest by starvation from the total destruction of crops in the region.

Map showing the distribution of the main ash cloud away from the eruption of Tambora, on the island of Sumbawa. Mt. Krakatau is in the strait between Java and Sumatra. (Courtesy Wikimedia Commons, used under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.)

Right after the eruption, the most definitive description of the volcano and its aftermath was given by Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, an ambassador of Britain in the area, the founder of Singapore, and a respected naturalist as well. As he wrote:

Island of Sumbawa, 1815—In April, 1815, one of the most frightful eruptions recorded in history occurred in the mountain Tambora, in the island of Sumbawa. It began on the 5th day of April, and was most violent on the 11th and 12th, and did not entirely cease till July. The sound of the explosion was heard in Sumatra, at a distance of nine hundred and seventy geographical miles in a direct line, and at Ternate, in an opposite direction, at the distance of seven hundred and twenty miles. Out of a population of twelve thousand, only twenty-six individuals survived on the island. Violent whirlwinds carried up men, horses, cattle, and whatever else came within their influence, into the air, tore up the largest trees by the roots, and covered the whole sea with floating timber. Great tracts of land were covered by lava, several streams of which, issuing from the crater of the Tambora mountain, reached the sea. So heavy was the fall of ashes, that they broke into the Resident’s house in Bima, forty miles east of the volcano, and rendered it, as well as many other dwellings in the town, uninhabitable. On the side of Java, the ashes were carried to the distance of three hundred miles, and two hundred and seventeen towards Celebes, in sufficient quantity to darken the air. The floating cinders to the westward of Sumatra formed, on the 12th of April, a mass two feet thick and several miles in extent, through which ships with difficulty forced their way. The darkness occasioned in the daytime by the ashes in Java was so profound, that nothing equal to it was ever witnessed in the darkest night. Although this volcanic dust, when it fell, was an impalpable powder, it was of considerable weight; when compressed, a pint of it weighing twelve ounces and three quarters. Along the sea-coast of Sumbawa, and the adjacent isles, the sea rose suddenly to the height of from two to twelve feet, a great wave rushing up the estuaries, and then suddenly subsiding. Although the wind at Bima was still during the whole time, the sea rolled in upon the shore, and filled the lower parts of houses with water a foot deep. Every prow and boat was forced from the anchorage and driven on shore. The area over which tremulous noises and other volcanic effects extended was one thousand English miles in circumference, including the whole of the Molucca Islands, Java, a considerable portion of Celebes, Sumatra and Borneo. In the island of Amboyna, in the same month and year, the ground opened, threw out water, and closed again.

Aerial view of Mt. Tambora today, showing the enormous caldera, still unvegetated 200 years after it blew its top. (Image by NASA Expedition 20 crew aboard International Space Station. Courtesy NASA, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Archeologists found the remains of a village, and two adults buried under approximately 10 feet of ash in a gully on Tambora’s flank during excavations in 2004. They were from the former Kingdom of Tambora. The volcano both destroyed the kingdom, and preserved its remains. The similarity of the Tambora remains to those associated with the eruption of Mount Vesuvius has led to the description of Tambora as the “the Pompeii of the East.”

Tambora had worldwide effects as well. It injected so much dust in the stratosphere that the earth’s weather patterns changed, and the dust blocked sunlight from reaching the surface. 1816 came to be known as the “Year without Summer” because it produced cold, dark rainy summer months in North America and Eurasia. This led to crop failures and starvation of livestock, and widespread disease (especially a typhus epidemic) and famine among populations around the world. It snowed in New York and New England in June, and also in many European cities. Europe was still recovering from the years of the Napoleonic Wars, so this climate even was catastrophic.

Finally, in Lord Byron’s villa near Lake Geneva in Switzerland, Percy and Mary Shelley were visiting and told gothic horror stories to pass the time in the cold, dark, wet summer. The inspiration of that gloomy time and the ghost stories they invented led Mary Shelley to write Frankenstein (published in 1818).

I still find it hard to get my around the fact that the Mount St.Helens eruption (which I vaguely remember as a kid) was around 100 times smaller than Tambora. It’s kind of difficult to wrap your head around what that must have been like to the local region.

I’d always thought Thera was one of the largest, if not the biggest, in human history. Was it just thought as large because it was in the Med, and thus the effects seemed magnified (big duck small pond), or does that part of the bronze age not count as recorded history?

No, Thera was nowhere near as big as Tambora, and barely bigger than Krakatau, based on the VEI (Volcano Explosivity Index), which is calculated from the amount of debris the volcano scattered across the planet. However, being in the center of human civilization at the time, it wiped out a lot more people, and had a much bigger effect on humanity, than volcanoes in distant Indonesia, where the population was smaller and much more remote to the main centers of human civilization.

We could use a major volcanic eruption about not to slow down global warming.

Unfortunately it would only have an effect that would last a couple of years and fuel science denialists, thus slowing down our ability to address the problem so that would count as yet another bad outcome from such an event. …

So if you find yourself being buried under 10′ of ash, just remember that every eruption has a silver lining. #Frankenstein.

Interesting article.