On The Cosmos

“The Cosmos is all that is or ever was or ever will be. Our feeblest contemplations of the Cosmos stir us — there is a tingling in the spine, a catch in the voice, a faint sensation, as if a distant memory, of falling from a height. We know we are approaching the greatest of mysteries.”

— “The Shores of the Cosmic Ocean,” Cosmos

On Extraterrestrial Intelligence

“There are some hundred billion (1011) galaxies, each with, on the average, a hundred billion stars. In all the galaxies, there are perhaps as many planets as stars, 1011 x 1011 = 1022, ten billion trillion. In the face of such overpowering numbers, what is the likelihood that only one ordinary star, the Sun, is accompanied by an inhabited planet? Why should we, tucked away in some forgotten corner of the Cosmos, be so fortunate? To me, it seems far more likely that the universe is brimming over with life. But we humans do not yet know. We are just beginning our explorations. The only planet we are sure is inhabited is a tiny speck of rock and metal, shining feebly by reflected sunlight, and at this distance utterly lost.”

— “The Shores of the Cosmic Ocean,” Cosmos

On Discovering Extraterrestrial Intelligences

“The receipt of a message from an advanced civilization will show that there are advanced civilizations, that there are methods of avoiding the self-destruction that seems so real a danger of our present technological adolescence… Finding a solution to a problem is helped enormously by the certain knowledge that a solution exists. This is one of many curious connections between the existence of intelligent life elsewhere and the existence of intelligent life on Earth.”

— “Knowledge is Our Destiny,” The Dragons of Eden

On Exploring the Cosmos

“This is the time when humans have begun to sail the sea of space. The modern ships that ply the Keplerian trajectories to the planets are unmanned. They are beautifully constructed, semi-intelligent robots exploring unknown worlds.”

— “Travelers’ Tales,” Cosmos

On the View of Earth From 3.7 Billion

Miles Away as a Pale Blue Dot

“Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home, That’s us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every ‘superstar,’ every ‘supreme leader,’ every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there — on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam… There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world. To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another, and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we’ve ever known.”

— “You Are Here,” Pale Blue Dot

On Comets

“Comets approach the Sun, flicker a few hundred times, and die like moths around a flame. But a vast repository of them waits at the periphery of the Solar System. When the present configuration of continents is unrecognizably altered, when the Earth is engulfed by the expanding Sun, when, in its dotage, our star feebly illuminates the charred remains of this planet — then, even then, the skies will still be brightened as young comets, newly arrived from the interstellar dark, make their wild perihelion passages. When the rest of the solar system is dead, and the descendants of humans long ago emigrated or extinct, the comets will still be here.”

— “A Mote of Dust,” Comet

On Childhood

“As soon as I was old enough, my parents gave me my first library card. I think the library was on 85th Street, an alien land. Immediately, I asked the librarian for something on stars. She returned with a picture book displaying portraits of men and women with names like Clark Gable and Jean Harlow. I complained, and for some reason then obscure to me, she smiled and found another book — the right kind of book. I opened it breathlessly and read until I found it. The book said something astonishing, a very big thought. It said that the stars were suns, only very far away. The Sun was a star, but close up.”

— “The Backbone of Night,” Cosmos

On Childhood Dreams of Being an Astronomer

“When I was twelve, my grandfather asked me — through a translator (he had never learned much English) — what I wanted to be when I grew up. I answered, ‘An astronomer,’ which, after a while, was also translated. ‘Yes,’ he replied, ‘but how will you make a living?’ I had supposed that, like all the adult men I knew, I would be consigned to a dull, repetitive, and uncreative job; astronomy would be done on weekends. It was not until my second year in high school that I discovered that some astronomers were paid to pursue their passion. I was overwhelmed with joy; I could pursue my interest full-time.”

— “Preface,” The Cosmic Connection

On the Brain

“The human brain seems to be in a state of uneasy truce, with occasional skirmishes and rare battles. The existence of brain components with predispositions to certain behavior is not an invitation to fatalism or despair: we have substantial control over the relative importance of each component. Anatomy is not destiny, but it is not irrelevant either.”

— “The Future Evolution of the Brain,” The Dragons of Eden

On Genes, Brains & Books

“When our genes could not store all the information necessary for survival, we slowly invented brains. But then the time came, perhaps ten thousand years ago, when we needed to know more than could conveniently be contained in brains. So we learned to stockpile enormous quantities of information outside our bodies. We are the only species on the planet, so far as we know, to have invented a communal memory stored neither in our genes nor in our brains. The warehouse of that memory is called the library.

A book is made from a tree. It is an assemblage of flat, flexible parts (still called “leaves”) imprinted with dark pigmented squiggles. One glance at it and you hear the voice of another person — perhaps someone dead for thousands of years. Across the millennia, the author is speaking, clearly and silently, inside your head, directly to you. Writing is perhaps the greatest of human inventions, binding together people, citizens of distant epochs, who never knew one another. Books break the shackles of time, proof that humans can work magic.”

— “The Persistence of Memory,” Cosmos

On Pseudoscience

“I worry that, especially as the Millennium edges nearer, pseudoscience and superstition will seem year by year more tempting, the siren song of unreason more sonorous and attractive. Where have we heard it before? Whenever our ethnic or national prejudices are aroused, in times of scarcity, during challenges to national self-esteem or nerve, when we agonize about our diminished cosmic place and purpose, or when fanaticism is bubbling up around us — then, habits of thought familiar from ages past reach for the controls. The candle flame gutters. Its little pool of light trembles. Darkness gathers. The demons begin to stir.”

— “Science and Hope,” The Demon-Haunted World

Why People Believe Nonsense

“Such reports persist and proliferate because they sell. And they sell, I think, because there are so many of us who want so badly to be jolted out of our humdrum lives, to rekindle that sense of wonder we remember from childhood, and also, for a few of the stories, to be able, really and truly, to believe in Someone older, smarter, and wiser who is looking out for us. Faith is clearly not enough for many people. They crave hard evidence, scientific proof. They long for the scientific seal of approval, but are unwilling to put up with the rigorous standards of evidence that impart credibility to that seal.”

— “The Man in the Moon and the Face on Mars,” The Demon-Haunted World

On Science Literacy

“All inquiries carry with them some element of risk. There is no guarantee that the universe will conform to our predispositions. But I do not see how we can deal with the universe — both the outside and the inside universe — without studying it. The best way to avoid abuses is for the populace in general to be scientifically literate, to understand the implications of such investigations. In exchange for freedom of inquiry, scientists are obliged to explain their work. If science is considered a closed priesthood, too difficult and arcane for the average person to understand, the dangers of abuse are greater. But if science is a topic of general interest and concern — if both its delights and its social consequences are discussed regularly and competently in the schools, the press, and at the dinner table — we have greatly improved our prospects for learning how the world really is and for improving both it and us.”

— “Broca’s Brain,” Broca’s Brain

On Science & Uncertainty

“We will always be mired in error. The most each generation can hope for is to reduce the error bars a little, and to add to the body of data to which error bars apply. The error bar is a pervasive, visible self-assessment of the reliability of our knowledge. You can often see error bars in public opinion polls… Imagine a society in which every speech in the Congressional Record, every television commercial, every sermon had an accompanying error bar or its equivalent.”

— “Science and Hope,” The Demon-Haunted World

On Humans & Animals

“We must stop pretending we’re something we are not. Somewhere between romantic, uncritical anthropomorphizing of the animals and an anxious, obdurate refusal to recognize our kinship with them — the latter made tellingly clear in the still-widespread notion of ‘special’ creation — there is a broad middle ground on which we humans can take our stand.”

— “Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors,” Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors

On Velikovsky

“In the entire Velikovsky affair, the only aspect worse than the shoddy, ignorant and doctrinaire approach of Velikovsky and many of his supporters was the disgraceful attempt by some who called themselves scientists to suppress his writings. For this, the entire scientific enterprise has suffered. Velikovsky makes no serious claim of objectivity or falsifiability. There is at least nothing hypocritical in his rigid rejection of the immense body of data that contradicts his arguments. But scientists are supposed to know better, to realize that ideas will be judged on their merits if we permit free inquiry and vigorous debate.”

— “Venus and Dr. Velikovsky,” Broca’s Brain

On Biology & History

“Biology is much more like language and history than it is like physics and chemistry… Now you might say that where the subject is simple, as in physics, we can figure out the underlying laws and apply them everywhere in the Universe; but where the subject is difficult, as in language, history, and biology, governing laws of Nature may well exist, but our intelligence may be too feeble to recognize their presence — especially if what is being studied is complex and chaotic, exquisitely sensitive to remote and inaccessible initial conditions. And so we invent formulations about “contingent reality” to disguise our ignorance. There may well be some truth to this point of view, but it is nothing like the whole truth, because history and biology remember in a way that physics does not. Humans share a culture, recall and act on what they’ve been taught. Life reproduced the adaptations of previous generations, and retains functioning DNA sequences that reach billions of years back into the past. We understand enough about biology and history to recognize a powerful stochastic component, the accidents preserved by high-fidelity reproduction.”

— “Life is Just a Three-Letter Word,” Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors

On God

“Because the word ‘God’ means many things to many people, I frequently reply (to people who ask ‘Do you believe in God?’) by asking what the questioner means by ‘God.’ To my surprise, this response is often considered puzzling or unexpected: ‘Oh, you know, God. Everyone knows who God is.’ Or ‘Well, kind of a force that is stronger than we are and that exists everywhere in the universe.’ There are a number of such forces. One of them is called gravity, but it is not often identified with God. And not everyone does know what is meant by ‘God.’ … Whether we believe in God depends very much on what we mean by God.

My deeply held belief is that if a god of anything like the traditional sort exists, our curiosity and intelligence are provided by such a god. We would be unappreciative of those gifts (as well as unable to take such a course of action) if we suppressed our passion to explore the universe and ourselves. On the other hand, if such a traditional god does not exist, our curiosity and our intelligence are the essential tools for managing our survival. In either case, the enterprise of knowledge is consistent with both science and religion, and is essential for the welfare of the human species.”

— “A Sunday Sermon,” Broca’s Brain

On Theism & Atheism

“Those who raise questions about the God hypothesis and the soul hypothesis are by no means all atheists. An atheist is someone who is certain that God does not exist, someone who has compelling evidence against the existence of God. I know of no such compelling evidence. Because God can be relegated to remote times and places and to ultimate causes, we would have to know a great deal more about the universe than we do now to be sure that no such God exists. To be certain of the existence of God and to be certain of the nonexistence of God seem to me to be the confident extremes in a subject so riddled with doubt and uncertainty as to inspire very little confidence indeed. A wide range of intermediate positions seems admissible, and considering the enormous emotional energies with which the subject is invested, a questioning, courageous and open mind seems to be the essential tool for narrowing the range of our collective ignorance on the subject of the existence of God.”

— “The Amniotic Universe,” Broca’s Brain

On a Plea for Tolerance

“We have held the peculiar notion that a person or society that is a little different from us, whoever we are, is somehow strange or bizarre, to be distrusted or loathed. Think of the negative connotations of words like alien or outlandish. And yet the monuments and cultures of each of our civilizations merely represent different ways of being human. An extraterrestrial visitor, looking at the differences among human beings and their societies, would find those differences trivial compared to the similarities. The Cosmos may be densely populated with intelligent beings. But the Darwinian lesson is clear: There will be no humans elsewhere. Only here. Only on this small planet. We are a rare as well as an endangered species. Every one of us is, in the cosmic perspective, precious. If a human disagrees with you, let him live. In a hundred billion galaxies, you will not find another.”

— “Who Speaks for Earth?,” Cosmos

On the Transience of Life

“Each of us is a tiny being, permitted to ride on the outermost skin of one of the smaller planets for a few dozen trips around the local star… The longest-lived organisms on Earth endure for about a millionth of the age of our planet. A bacterium lives for one hundred-trillionth of that time. So of course the individual organisms see nothing of the overall pattern — continents, climate, evolution. They barely set foot on the world stage and are promptly snuffed out — yesterday a drop of semen, as the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius wrote, tomorrow a handful of ashes. If the Earth were as old as a person, a typical organism would be born, live, and die in a sliver of a second. We are fleeting, transitional creatures, snowflakes fallen on the hearth fire. That we understand even a little of our origins is one of the great triumphs of human insight and courage.”

— “Snowflakes Fallen on the Hearth,” Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors

On Life & Death

“Most people would rather be alive than dead. But why? It’s hard to give a coherent answer. An enigmatic “will to live” or “life force” is often cited. But what does that explain? Even victims of atrocious brutality and intractable pain may retain a longing, sometimes even a zest, for life. Why, in the cosmic scheme of things, one individual should be alive and not another is a difficult question, an impossible question, perhaps even a meaningless question. Life is a gift that, of the immense number of possible but unrealized beings, only the tiniest fraction are privileged to experience. Except in the most hopeless of circumstances, hardly anyone is willing to give it up voluntarily — at least until very old age is reached.”

— “What Thin Partitions…,” Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors

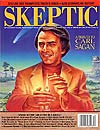

This article can be found in

volume 04 number 04

Carl Sagan Tribute

this issue includes: Can History Be Science?; Sulloway on Born to Rebel; Debunking Nostradamus; Critical Thinking About History; Left and Right Science; What Happened to N-Rays?…

BROWSE this issue >

ORDER this issue >

This article was published on October 1, 2009.

When I first saw carl sagans..series the cosmos, I knew that I was witnessing true intelligence, even as a know nothing thirteen year old I was fascinated by him, I was especially impressed with his use of pink floyds..one of these days, as he traveled through the cosmos. Many are called few are chosen. Now thirty years later, I have an immense appreciation for both. I would also like to thank. Michael. Shermer for his commitment to the search for answers, instead of listening to the habadachery forced down our throats by the status quo..ever since we were little children.

you inspired me at the beginning , i lost you in the middle and im glad to have found you once again

I love you, Carl, and I am so sad you are gone, because that means no more books, and YOU were my favorite author.

No words, in any language, can begin to describe the loss, of someone, like Carl.

He, who could begin to explain, the most complex questions, with such simple answers, and yet, get to the root, of it all!!

Yes Carl, we are not alone, but they have not touched us yet!

The first contact, would be, INCREDIBLE!!

Thank you, so much, for showing us the WAY…………..

A visionary that will be sadly missed.