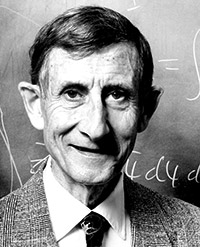

Freeman Dyson is a retired professor of physics at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, New Jersey. He has published many books about science for the general public, including Disturbing the Universe (1979) and The Scientist as Rebel (2006).

Carl Sagan saw a vision of human space-explorers venturing out into the universe, following the great tradition of the sailors who ventured out onto the oceans and began to explore the continents of this planet 500 years earlier. But Carl was not only a romantic visionary; he was also a professional scientist. His professional life was devoted to understanding the planets with the tools of modern science. He knew that the acquisition of scientific knowledge about the planets must be done with robotic instruments before human explorers could make a useful contribution. He played a large role in the planning and execution of robotic missions to Mars and the other planets. His own studies of the planets were solidly based in science, and yet he was aware that science is not the main driving force of space-exploration.

Like the terrestrial explorers in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries who went in search of gold and spices rather than scientific knowledge, Carl saw the outward movement of humans from this planet as an enterprise with wider aims than science. His vision, which he proclaimed in 1973 in his book, The Cosmic Connection, and in his incomparable television performances, was space exploration as a human adventure. He succeeded, more than anyone else of his generation, in giving science a human face. He saw the cosmic connection as an enlargement of the human spirit. He wanted everyone on Earth, and not only the scientific élite, to feel connected with the cosmos.

Carl’s vision had two aspects, the long-range and the short-range. The long-range aspect was the awakening of humankind to an awareness of the majesty of the cosmos and the possibility of extraterrestrial life. The short-range aspect was a program of human activities in space to be pursued during the last three decades of the 20th century. History has treated the two parts of his vision very differently. The long-range part is off to a good start, while the short-range part has failed miserably.

The main reason why Carl’s short-range vision failed was that he put too much trust in fallible human institutions. He served three masters, NASA, Hollywood, and science, and believed that he could keep them working harmoniously together. He recognized no conflict between scientific integrity and political expediency. NASA would provide opportunities for human explorers to travel far and wide, Hollywood would educate the public, astronomers and planetary scientists would understand the cosmos, and Carl would be a leader and guide in all three enterprises. He expected international manned expeditions to the planets and self-sustaining colonies on the moon before the end of the 20th century. He expected at least one large telescope to be built and dedicated to a search for extraterrestrial civilizations.

Now the end of the twentieth century is past. There are no colonies on the moon and no manned expeditions to planets. The dream of a rapid expansion of human voyages into the cosmos has faded. The International Space Station falls ludicrously short of Carl’s expectations for a pioneering space venture. It is not doing much either for science or for human adventure. It stays in a low orbit around the Earth, a welfare program for American and Russian aerospace industries, driven by mundane politics rather than by visions of cosmic connections.

Carl’s disappointments, in his dealings with NASA and Hollywood, were similar to Mozart’s disappointments in his dealings with the Archbishop of Salzburg and the Emperor of Austria. Carl shared many of Mozart’s qualities. He had personal charm, technical brilliance, and a robust sense of humor masking his underlying seriousness. Carl and Mozart were both creative spirits, both dependent on patrons, both impatient with the formalities that patronage demands, and both taking it for granted that the patron should continue to give them unqualified support. To both of them, it came as a bitter disappointment when the patron withdrew support or imposed conditions that limited their freedom.

Nevertheless, while Carl’s short-range visions were frustrated, his long-range vision thrived. He founded and led the Planetary Society, bringing scientists and ordinary citizens together to promote the long-range goals of exploration and education. The Planetary Society became a powerful voice in Washington, giving political support to publicly funded space missions. It also became an important source of money for privately funded observations searching for extraterrestrial intelligence. For three decades Carl was the preeminent voice of science speaking to the broad public.

In television shows, films, and books, he used his gifts as a performer to dramatize the excitement of exploring and the joy of discovery. He was a great teacher. He knew how to spice his gospel of cosmic connection with stories and jokes, so that he did not seem to be preaching. His audiences came to his performances to be entertained and went away converted. In the end he succeeded, in spite of failures and disappointments, in changing our view of our planet and changing the way we think about the universe.

This article can be found in

volume 13 number 1

The Legacy of Carl Sagan

this issue includes: An Interview with Ann Druyan; Science, Religion & Human Purpose; An excerpt from Conversations with Carl; Tributes to Carl Sagan…

BROWSE this issue >

This issue is sold out.

This article was published on October 2, 2009.