From the Ordinary to the Extraordinary

Rising temperatures, biodiversity loss, drought, mass migration, the spread of misinformation, inflation, infertility—these are just some of the major challenges facing societies around the globe. Generating innovative solutions to such challenges requires expanding our understanding of what’s currently possible. But how do we cultivate the necessary imagination? By debunking counterproductive myths about imagination, Occidental College cognitive developmental scientist Andrew Shtulman might just provide us with a starting point. “Unstructured imagination succumbs to expectation,” he writes, “but imagination structured by knowledge and reflection allows for innovation.” (p. 12)

Imagination Myths

In Learning to Imagine: The Science of Discovering New Possibilities, Shtulman challenges the highly intuitive, yet obstructive notion that great imagination stems from a place of ignorance. Through the sharing of everyday examples and detailed experimental studies, Shtulman effectively tackles the pervasive deficit view of imagination—that it’s something we engage in a great deal during childhood and sadly lose as we get older.

Contrary to the conventional wisdom, Shtulman demonstrates that children’s imagination, relative to adults’, is constrained by what they think is physically plausible, statistically probable, and socially and morally acceptable. While some early philosophers and social scientists considered children to be lacking intelligence and their minds to be a blank slate, a contemporary swing of the pendulum has led to a confusing romanticization of children as “little scientists” capable of unacknowledged insight. A more informed view recognizes that though children’s minds are not blank slates, they do often conflate what they’ve personally experienced with what “could be.” To a child’s mind, what they can’t imagine, can’t exist.

“Unstructured imagination succumbs to expectation, but imagination structured by knowledge and reflection allows for innovation.” —Andrew Shtulman

Shtulman notes how young children often deny the existence of uncommon but entirely possible events, such as finding an alligator under a bed, catching a fly with chopsticks, and a man growing a beard down to his toes. Children find these situations as impossible as eating lightning for dinner. While children often engage in pretend play, it often mimics mundane aspects of real life, such as cooking or construction. Children also often believe in magic and fantastical beings such as Santa Claus, but such myths were not spontaneously created by children, they were first endorsed by adults they trust. Children rarely generate novel solutions to problems as they tend to fixate on the rules and norms familiar to them, often correcting others when they have deviated from what is expected and sometimes become offended by “rule” violations.

Learning to Imagine is not only about children’s cognition; it is fundamentally a book about human reasoning and contains insights that are applicable to all of us. Shtulman sheds light on the many important ways in which adults continue to constrain their own imagination through self-interest, habit, fear, and a fixation on conforming to one’s social group. For example, we may constrain ourselves with resistance to adopting new technologies like artificial intelligence because they reduce the need for our skillset or simply engender fear of the unknown. We may resist something that requires us to change our habits (e.g., carrying reusable bags), to something that forces us to take risks (e.g., trusting a quickly developed vaccine), or to deviate from our in-group (e.g., advocating for a new theory or openly sharing an unpopular opinion).

What is Imagination, Anyhow?

So, just what is imagination? Shtulman argues that it is the ability to abstract from the here and the now, to contemplate what could be or what could have been. Imagination is an evolved cognitive skill that is used for the purpose of everyday planning, predicting, and problem-solving. We imagine what we would buy at the store, how a meeting at work might go, how if we had only said something a different way, then we could have avoided that fight with our spouse, and so on. Simply put, imagination is the ability to ask “What’s possible?”. Imagination can be engaged in for our subjective experiences (e.g., imagining how life would have been different if path B was chosen instead of path A), and for what might be more relevant to others (e.g., works of art, new policies, technologies).

Simply put, imagination is the ability to ask “What’s possible?”.

Even though Shtulman’s case for imagination is grounded in this “what’s possible” definition, how it is intertwined with closely related constructs such as “creativity” and “innovation” is somewhat less clear. What can be discerned from his book is that while imagination can be collaborative in the sense that we draw on human knowledge to ask, “what if,” it is largely a personal endeavor. Creativity, on the other hand, is the product of imagination that can be shared with others. Building upon imagination and creativity, innovation is the product of extraordinary imagination and can be developed and refined.

Mechanisms for Expanding What’s Possible

What are the proposed means by which we expand our knowledge, thereby improving the likelihood that we shift our imagination from the ordinary to the extraordinary? Shtulman outlines three ways of learning, specifically through: (1) examples, (2) principles, and (3) models.

The first mechanism, learning through examples, involves learning about new possibilities via other people’s testimony, demonstrations, empirical discoveries, and technological creations. Through education, others’ knowledge becomes our knowledge. However, expanding our imagination through examples is the easiest but also the most limited means by which to expand our own. On one hand, new possibilities are added to our database of what could be, but in doing so, we are potentially limited by overly fixating on the suboptimal (yet adequate) solution we have learned; as Shtulman notes, we “privilege [our] expectation over observation.” For example, we tend to copy the necessary and unnecessary actions of others when trying to achieve the same goal—we fixate on the solution we are familiar with rather than engage in the little effort required to abstract a more efficient solution. Children are even more susceptible to such a process. For example, imagine you see a toy with a handle that is stuck at the bottom of a long tube, and you are provided with a straight pipe cleaner. How might you reach and retrieve the toy? You likely imagine bending the pipe cleaner, yet most preschoolers tasked to reach the toy in this scenario are unable to imagine how the pipe cleaner can be used as a sufficient tool.

The second mechanism, learning through principles, refers to generating a new collection of possibilities by learning about abstract theories about “how” and “why” things operate. These include learning about scientific/cause-and-effect, mathematical, and ethical principles. As a means for expanding imagination, principles are more valuable than examples because they can help us extrapolate possibilities from one situation and apply it across different domains. One illustrative example is the physicist Ernest Rutherford, who won a Nobel prize in chemistry. Rutherford hypothesized (correctly) that electrons, like planets orbiting a sun, may orbit a nucleus. By using the principle of gravity and applying it in a different context, Rutherford generalized an insight from physics to innovate in the field of chemistry. Engaging with principles allows us to practice applying our knowledge and better understand novel relationships. While most of us are not scientists striving to win a Nobel prize, we can still learn new principles that expand our imagination. However, principles can be overgeneralized, and Shtulman argues that new applications should still be tested and replicated to confirm the connection.

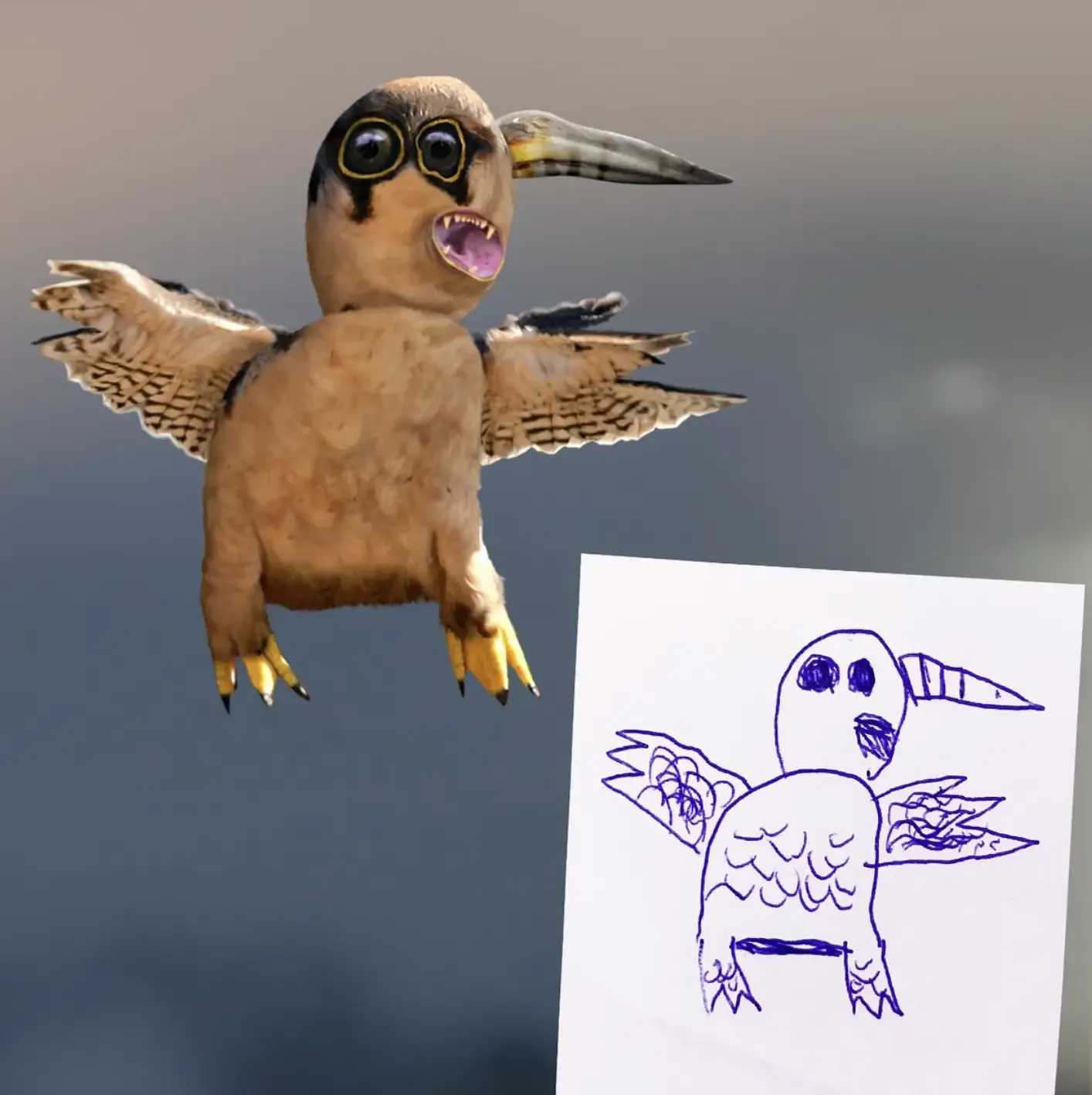

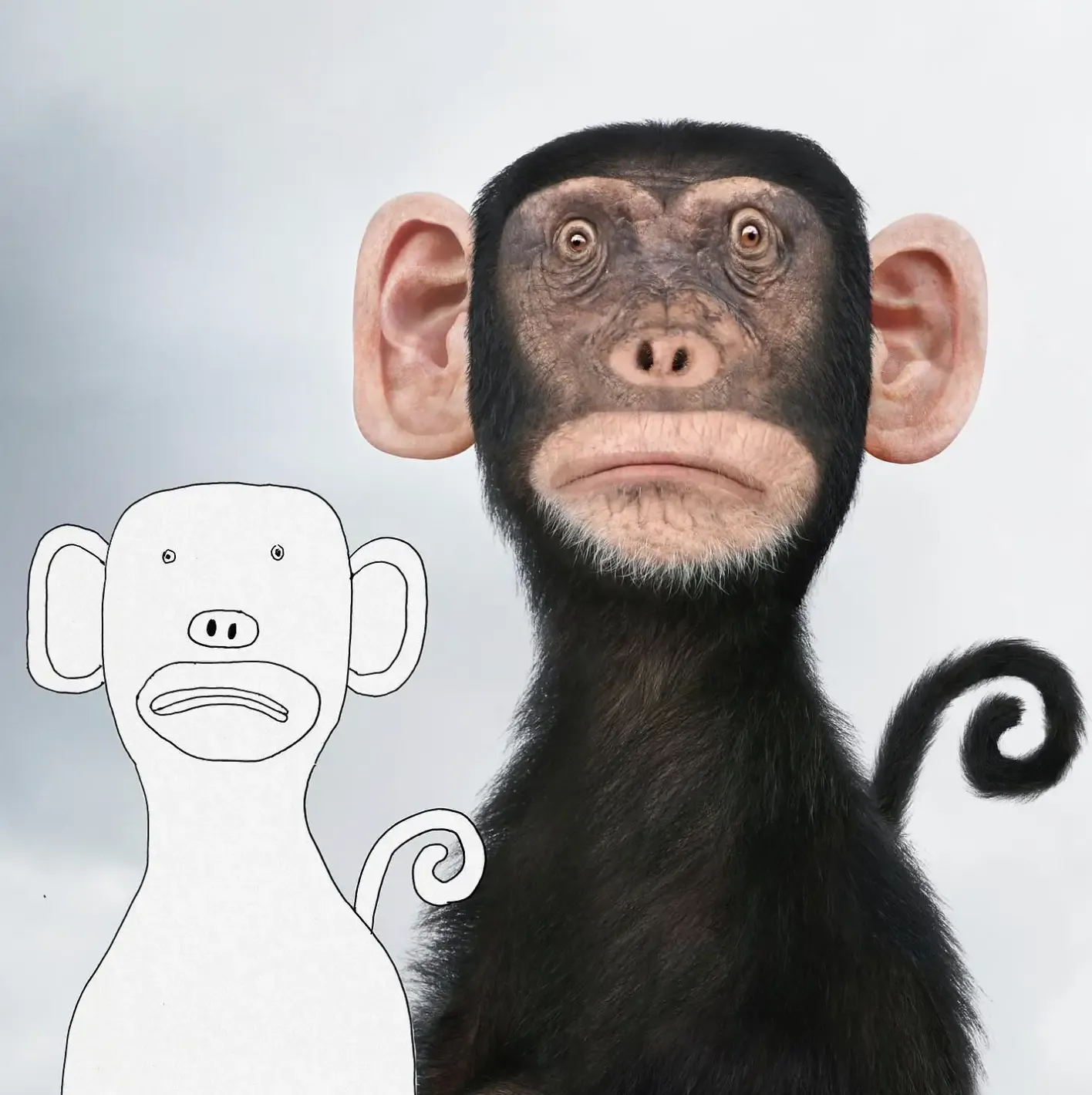

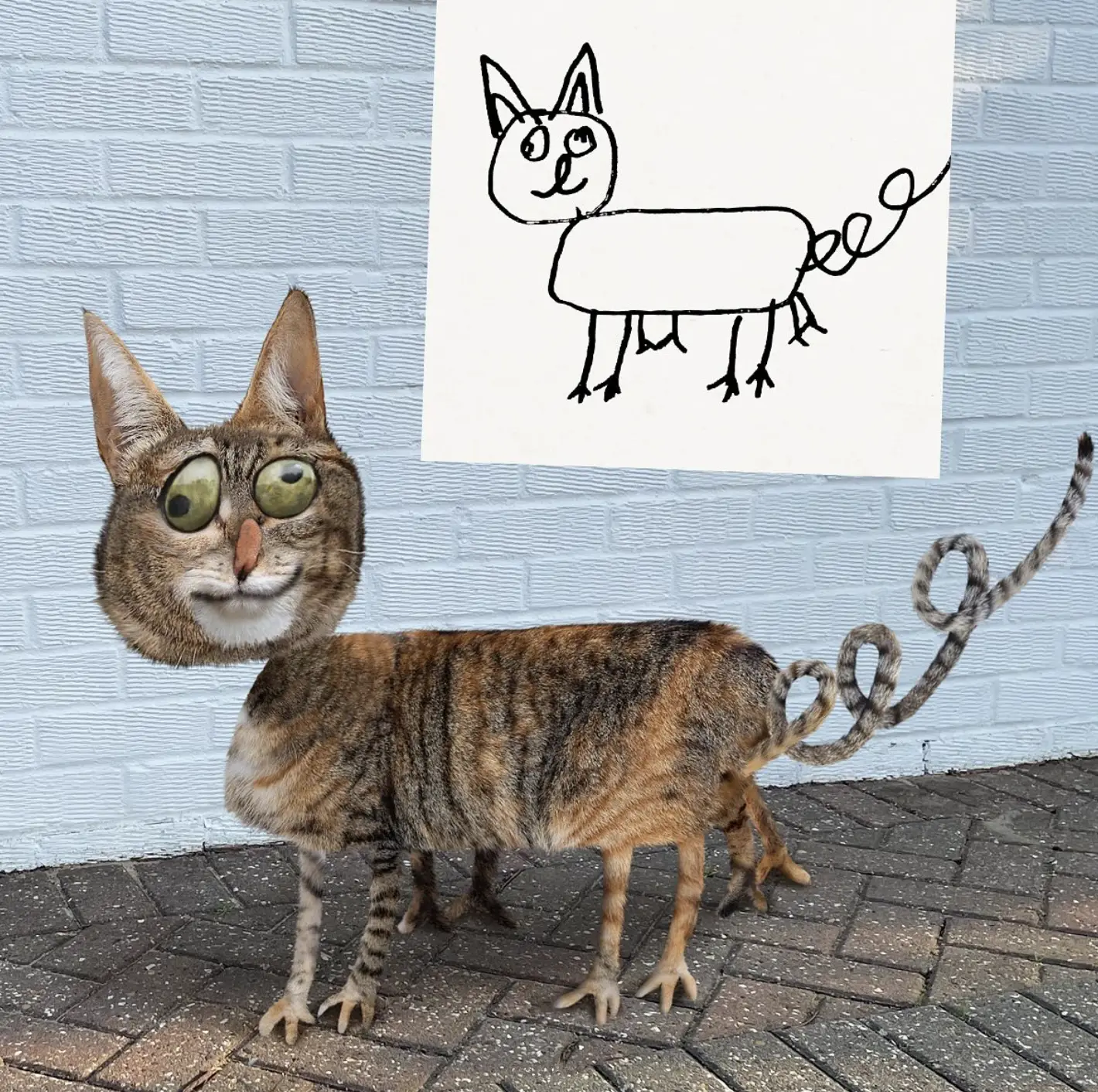

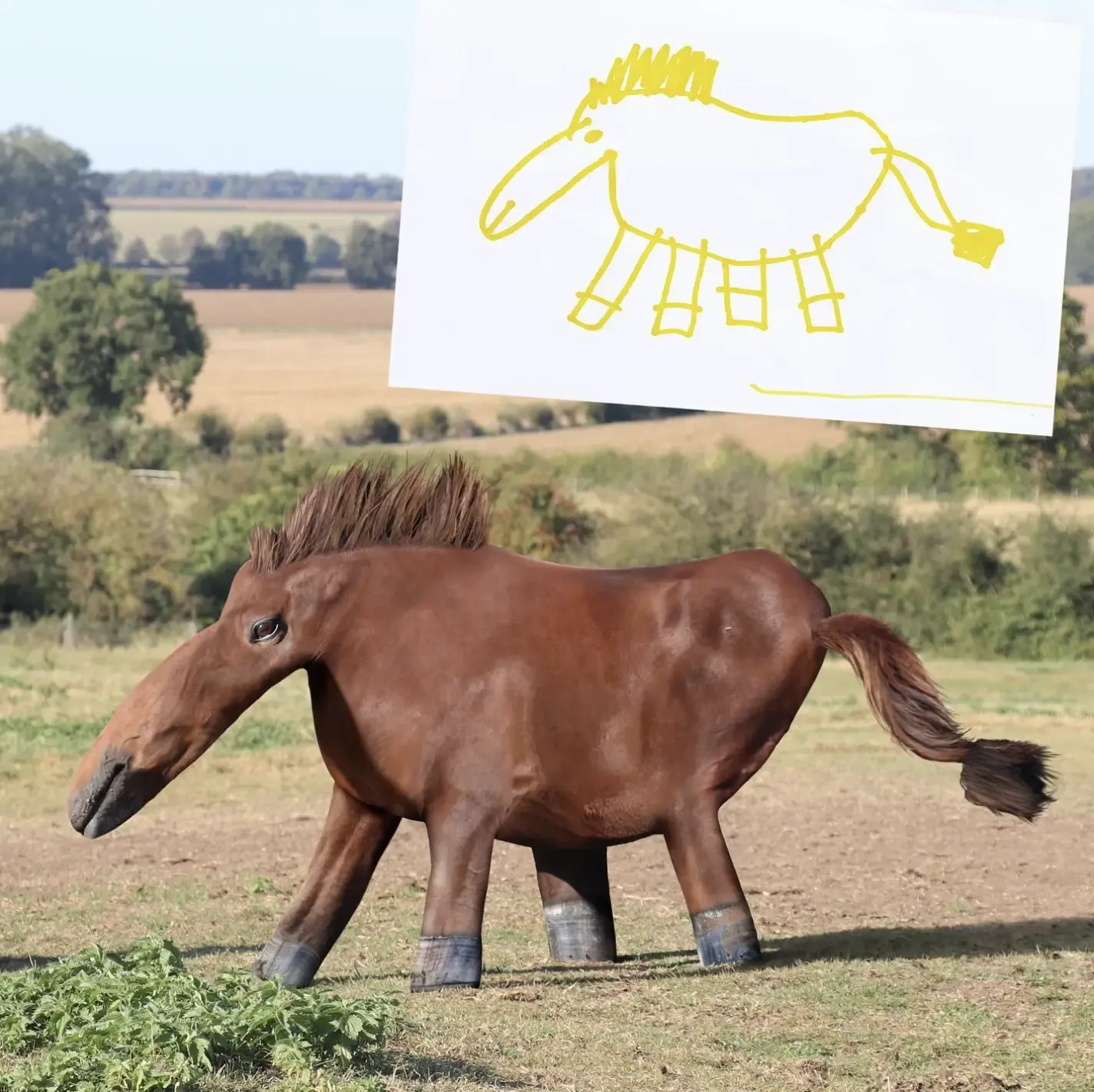

An artist recreates childrens’ drawings as if they were real creatures. (Source: Things I Have Drawn)

The third mechanism, learning through models, might be the most exciting as it concerns expanding our ideas about what is possible by immersing ourselves in simulated versions of reality that can be manipulated with little to no consequences. These simulations allow for personal reflection through the process of mental time travel. This includes expanding our imagination through pretense (i.e., pretend play), fiction, and religion. Pretense allows us to expand our symbolic imagination by toying with alternative possibilities somewhat rooted in reality because the real-world elements of pretend play help to make it meaningful. For example, when children and many adults are asked to draw an animal that doesn’t exist, the product is usually an amalgamation of existing animal parts rather than a completely unique creature. Such mental play supports the development of logical reasoning. Through different mediums such as books and film, fiction expands our imagination by allowing us to experience the social world through the eyes and thoughts of others. We see how others react to situations we haven’t experienced and contemplate how we might respond if we were in their shoes.

“You have to represent reality before you can tinker with it, to know the facts before you can entertain counterfactuals.” —Andrew Shtulman

Religion is rooted less in the here and now but may enable us to expand metaphysical ideas and explore moral reasoning by directing thoughts and behavior according to the core values of a specific religion. Ultimately, models allow us to experience the lessons of working out various problems without the risks associated with acting on them in real life. On the other hand, sometimes models may communicate false information that we mark as true. Though models may sometimes lead us astray, Shtulman argues that they “provide the raw materials. … You have to represent reality before you can tinker with it, to know the facts before you can entertain counterfactuals” (p. 12).

The numerous examples that Shtulman provides for how examples, principles, and models expand imagination generate a convincing case for the central thesis of his book—that, unlike the current conventional wisdom, children’s lack of knowledge, experience, and reflection make them less imaginative than adults. However, attempts to distinguish many overlapping concepts within in the book (e.g., religious models vs. fictional models; social imagination vs. moral imagination) is sometimes disorientating.

Should You Read This Book?

Will this book provide you with a specific list of ways to quickly develop a more “imaginative mindset” for yourself and others? No, it is not a self-help book. Instead, you’ll spend hours on an engaging (and, dare we say, nourishing) tour of the limitations and achievements of human imagination. By the end, you’ll know a lot more about how the human mind develops and reasons, and about the cognitive mechanisms that impede and enhance innovation across eras, societies, and an individual lifetime. Through your newfound knowledge, you may begin to imagine solutions to both personal and global challenges that you hadn’t considered before.