The New Zealand Māori Astrology Craze: A Case Study

“It is fundamental in science that no knowledge is protected from challenge. … Knowledge that requires protection is belief, not science.” —Peter Winsley

There is growing international concern over erosion of objectivity in both education and research. When political and social agendas enter the scientific domain there is a danger that they may override evidence-based inquiry and compromise the core principles of science. A key component of the scientific process is an inherent skeptical willingness to challenge assumptions. When that foundation is replaced by a fear of causing offense or conforming to popular trends, what was science becomes mere pseudoscientific propaganda employed for the purpose of reinforcing ideology.

When Europeans formally colonized New Zealand in 1840 with the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, the culture of the indigenous Māori people was widely disparaged and their being viewed an inferior race. One year earlier historian John Ward described Māori as having “the intellect of children” who were living in an immature society that called out for the guiding hand of British civilization.1 The recognition of Māori as fully human, with rights, dignity, and a rich culture worthy of respect, represents a seismic shift from the 19th century attitudes that permeated New Zealand and much of the Western world, and that were used to justify the European subjugation of indigenous peoples.

Since the 1970s, Māori society has experienced a cultural Renaissance with a renewed appreciation of the language, art, and literature of the first people to settle Aotearoa—“the land of the long white cloud.” While speaking Māori was once banned in public schools, it is now thriving and is an official language of the country. Learning about Māori culture is an integral part of the education system that emphasizes that it is a treasure (taonga) that must be treated with reverence. Māori knowledge often holds great spiritual significance and should be respected. Like all indigenous knowledge, it contains valuable wisdom obtained over millennia, and while it contains some ideas that can be tested and replicated, it is not the same as science.

When political and social agendas enter the scientific domain there is a danger that they may override evidence-based inquiry

For example, Māori knowledge encompasses traditional methods for rendering poisonous karaka berries safe for consumption. Science, on the other hand, focuses on how and why things happen, like why karaka berries are poisonous and how the poison can be removed.2 The job of science is to describe the workings of the natural world in ways that are testable and repeatable, so that claims can be checked against empirical evidence—data gathered from experiments or observations. That does not mean we should discount the significance of indigenous knowledge—but these two systems of looking at the world operate in different domains. As much as indigenous knowledge deserves our respect, we should not become so enamoured with it that we give it the same weight as scientific knowledge.

The Māori Knowledge Debate

In recent years the government of New Zealand has given special treatment to indigenous knowledge. The issue came to a head in 2021, when a group of prominent academics published a letter expressing concern that giving indigenous knowledge parity with science could undermine the integrity of the country’s science education. The seven professors who signed the letter were subjected to a national inquisition. There were public attacks by their own colleagues and an investigation by the New Zealand Royal Society on whether to expel members who had signed the letter.3

Ironically, part of the reason for the Society’s existence is to promote science. At its core is the issue of whether “Māori ancient wisdom” should be given equal status in the curriculum with science, which is the official government position.4 This situation has resulted in tension in the halls of academia, where many believe that the pendulum has now swung to another extreme. Frustration and unease permeate university campuses as professors and students alike walk on eggshells, afraid to broach the subject for fear of being branded racist and anti-Māori, or subjected to personal attacks or harassment campaigns.

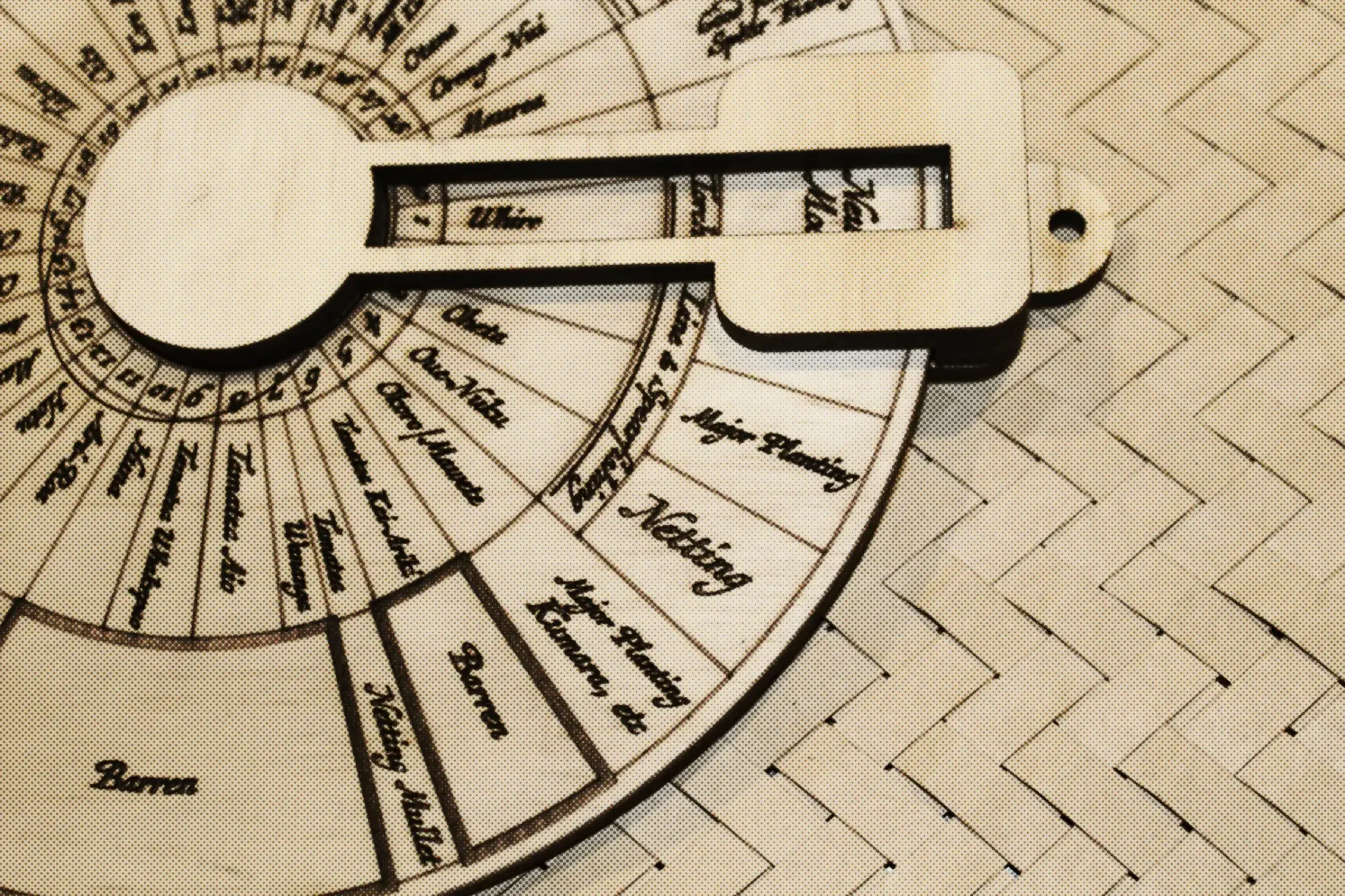

The Lunar Calendar

Infatuation with indigenous knowledge and the fear of criticising claims surrounding it has infiltrated many of the country’s key institutions, from the health and education systems to the mainstream media. The result has been a proliferation of pseudoscience. There is no better example of just how extreme the situation has become than the craze over the Māori Lunar Calendar. Its rise is a direct result of what can happen when political activism enters the scientific arena and affects policymaking. Interest in the Calendar began to gain traction in late 2017.

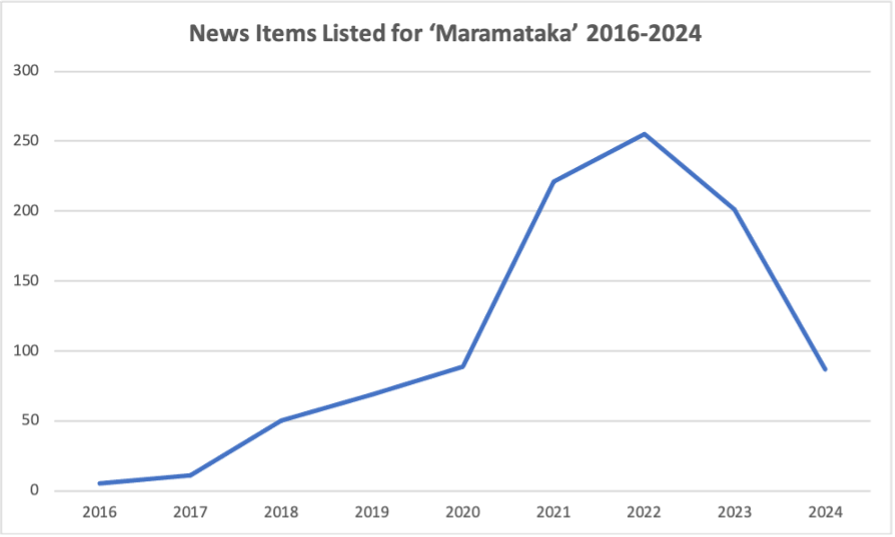

Since then, many Kiwis have been led to believe that it can impact everything from horticulture to health to human behavior. The problem is that the science is lacking, but because of the ugly history of the mistreatment of the Māori people, public institutions are afraid to criticize or even take issue anything to do with Māori culture. Consider, for example, media coverage. Between 2020 and 2024, there were no less than 853 articles that mention “maramataka”—the Māori word for the Calendar which translates to “the turning of the moon.” After reading through each text, I was unable to identify a single skeptical article.5 Many openly gush about the wonders of the Calendar, and gave no hint that it has little scientific backing.

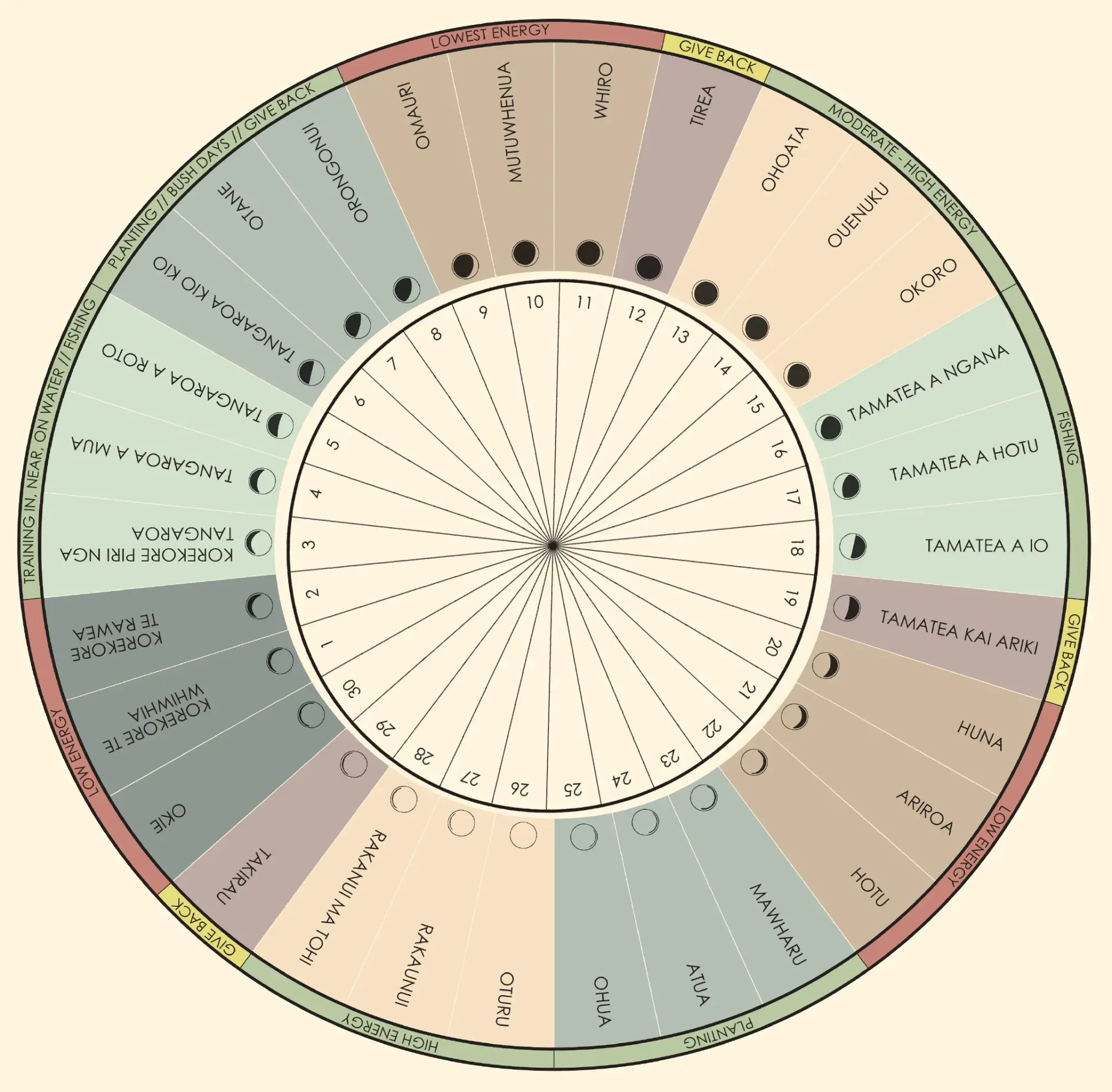

The Calendar once played an important role in Māori life, tracking the seasons. Its main purpose was to inform fishing, hunting, and horticultural activities. There is some truth in the use of specific phases or cycles to time harvesting practices. For instance, some fish are more active or abundant during certain fluctuations of the tides, which in turn are influenced by the moon’s gravitational pull. Two studies have shown a slight increase in fish catch using the Calendar.6 However, there is no support for the belief that lunar phases influence human health and behavior, plant growth, or the weather. Despite this, government ministries began providing online materials that feature an array of claims about the moon’s impact on human affairs. Fearful of causing offense by publicly criticizing Māori knowledge, the scientific position was usually nowhere to be found.

Soon primary and secondary schools began holding workshops to familiarize staff with the Calendar and how to teach it. These materials were confusing for students and teachers alike because most were breathtakingly uncritical and there was an implication that it was all backed by science. Before long, teachers began consulting the maramataka to determine which days were best to conduct assessments, which days were optimal for sporting activities, and which days were aligned with “calmer activities at times of lower energy phases.” Others used it to predict days when problem students were more likely to misbehave.7

Fearful of causing offense by publicly criticizing Māori knowledge, the scientific position was usually nowhere to be found.

As one primary teacher observed: “If it’s a low energy day, I might not test that week. We’ll do meditation, mirimiri (massage). I slowly build their learning up, and by the time of high energy days we know the kids will be energetic. You’re not fighting with the children, it’s a win-win, for both the children and myself. Your outcomes are better.”8 The link between the Calendar and human behavior was even promoted by one of the country’s largest education unions.9 Some teachers and government officials began scheduling meetings on days deemed less likely to trigger conflict,10 while some media outlets began publishing what were essentially horoscopes under the guise of ‘ancient Māori knowledge.’11

The Calendar also gained widespread popularity among the public as many Kiwis began using online apps and visiting the homepages of maramataka enthusiasts to guide their daily activities. In 2022, a Māori psychiatrist published a popular book on how to navigate the fluctuating energy levels of Hina—the moon goddess. In Wawata Moon Dreaming, Dr. Hinemoa Elder advises that during the Tamatea Kai-ariki phase people should: “Be wary of destructive energies,”12 while the Māwharu phase is said to be a time of “female sexual energy … and great sex.”13 Elder is one of many “maramataka whisperers” who have popped up across the country.

By early 2025, the Facebook page “Maramataka Māori” had 58,000 followers,14 while another, “Living by the Stars” on Māori Astronomy had 103,000 admirers.15 Another popular book, Living by the Moon, also asserts that lunar phases can affect a person’s energy levels and behavior. We are told that the Whiro phase (new moon) is associated with troublemaking. It even won awards for best educational book and best Māori language resource.16 In 2023, Māori politician Hana Maipi-Clarke, who has written her own book on the Calendar, stood up in Parliament and declared that the maramataka could foretell the weather.17

A Public Health Menace

Several public health clinics have encouraged their staff to use the Calendar to navigate “high energy” and “low energy” days and help clients apply it to their lives. As a result of the positive portrayal of the Calendar in the Kiwi media and government websites, there are cases of people discontinuing their medication for bipolar disorder and managing contraception with the Calendar.18 In February 2025, the government-funded Māori health organization, Te Rau Ora, released an app that allows people to enhance their physical and mental health by following the maramataka to track their mauri (vital life force).

While Te Rau Ora claims that it uses “evidence-based resources,” there is no evidence that mauri exists, or that following the phases of the moon directly affects health and well-being. Mauri is the Māori concept of a life force—or vital energy—that is believed to exist in all living beings and inanimate objects. The existence of a “life force” was once the subject of debate in the scientific community and was known as “vitalism,” but no longer has any scientific standing.19 Despite this, one of app developers, clinical psychologist Dr. Andre McLachlan, has called for widespread use of the app.20 Some people are adamant that following the Calendar has transformed their lives, and this is certainly possible given the belief in its spiritual significance. However, the impact would not be from the influence of the Moon, but through the power of expectation and the placebo effect.

No Science Allowed

While researching my book, The Science of the Māori Lunar Calendar, I was repeatedly told by Māori scholars that it was inappropriate to write on this topic without first obtaining permission from the Māori community. They also raised the issue of “Māori data sovereignty”—the right of Māori to have control over their own data, including who has access to it and what it can be used for. They expressed disgust that I was using “Western colonial science” to validate (or invalidate) the Calendar.

It is a dangerous world where subjective truths are given equal standing with science under the guise of relativism.

This is a reminder of just how extreme attempts to protect indigenous knowledge have become in New Zealand. It is a dangerous world where subjective truths are given equal standing with science under the guise of relativism, blurring the line between fact and fiction. It is a world where group identity and indigenous rights are often given priority over empirical evidence. The assertion that forms of “ancient knowledge” such as the Calendar, cannot be subjected to scientific scrutiny as it has protected cultural status, undermines the very foundations of scientific inquiry. The expectation that indigenous representatives must serve as gatekeepers who must give their consent before someone can engage in research on certain topics is troubling. The notion that only indigenous people can decide which topics are acceptable to research undermines intellectual freedom and stifles academic inquiry.

While indigenous knowledge deserves our respect, its uncritical introduction into New Zealand schools and health institutions is worrisome and should serve as a warning to other countries. When cultural beliefs are given parity with science, it jeopardizes public trust in scientific institutions and can foster misinformation, especially in areas such as public health, where the stakes are especially high.