Who Runs the News? The Tug-of-War Between Shareholders and Journalists

“The paper’s duty will remain to its readers and not to the private interests of its owners.”

Those are the reassuring words that Jeff Bezos wrote1 to The Washington Post’s employees when he acquired that major newspaper in 2013.

Fast forward 12 years to the present: Recently, Bezos took to the social media platform X to announce a bold new shift in the paper’s editorial policy. From now on, the Opinion section will be dedicated to supporting and defending “free markets” and “personal liberties.”

“These viewpoints are underserved in the current market of ideas and news opinion,” wrote Bezos. He then spelled out in no uncertain terms, “Opinion pieces not centered on these approved topics will no longer be published here.”

Translation: Dissenting viewpoints need not apply.

Predictably, outrage erupted and many rushed to condemn Bezos. Opinion editor David Shipley resigned (“I suggested to him that if the answer wasn’t ‘hell yes’ then it had to be ‘no,’” explained Bezos). Meanwhile, others celebrated this shift as a turning-of-the-tide.

The irony is that, not too long ago, many of the same people applauding Bezos were once fiercely critical of what they consider to be left-leaning publications such as The New York Times, The Washington Post, and Newsweek for having opinion sections that were more biased against conservative or Republican viewpoints. Yet, even in those pages, conservative viewpoints would sometimes surface—usually penned by industry titans, political heavyweights, or intellectuals with Ivy League credentials.

At the end of the day, Bezos owns the Post. He can do what he likes with it—it’s his funhouse to run, his editorial roller coaster. However, his decision speaks to a broader tension in modern media: Should newspapers strive for ideological balance, or is it better to just be upfront about their biases?

According to Bezos: “There was a time when a newspaper, especially one that was a local monopoly, might have seen it as a service to bring to the reader’s doorstep every morning a broad-based opinion section that sought to cover all views. Today, the internet does that job.”

The internet, while certainly filled with opinions, hardly does the same job as a professional publication. The Internet is a swamp of opinions—some insightful, some deranged, some written by anonymous bots. One can certainly sift through and find worthwhile opinions, but a good Opinion section at a paper, ideally, provides readers with a curated selection of opinions, based on the high-quality of argument—not the number of likes it gets on social media. Opinion sections, unlike news reporting (where bias and ideology may sneak in covertly), allow readers to engage with bias knowingly. The readers are already well aware that each opinion essay represents the views of each author.

One could argue that Bezos’s approach simply formalizes what already exists elsewhere. The Wall Street Journal leans pro-business, The Guardian leans left. WaPo is just following suit—choosing to champion a specific ideological framework rather than trying to please everyone or pretending to be neutral and trying to please everyone.

“Opinion pieces not centered on these approved topics will no longer be published here.” —Jeff Bezos

In today’s hyper-polarized media environment, readers gravitate toward outlets that affirm their beliefs. But that’s not necessarily something new. When the U.S. was founded, newspapers played a critical role in shaping public opinion and were openly partisan. In other words, the press was meant to persuade, not necessarily to inform in an objective sense.

Federalist newspapers supported a strong central government, whereas Jeffersonian papers attacked proponents of centralized power and advocated for a Bill of Rights to protect individual liberties, an agrarian democracy, and a limited federal government. The Federalist Papers were originally published as a series of essays2 across three New York-based papers: The Independent Journal, The New York Packet, and The Daily Advertiser in 1787–1788. Written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay under the pseudonym Publius, they aimed to persuade the public and state legislatures to ratify the Constitution. Meanwhile, the Anti-Federalist Papers—which are less known—opposed the new Constitution and argued for a Bill of Rights to protect individual liberties. They too appeared in newspapers across different states.

Early newspapers in the U.S. weren’t merely filled with partisan opinion, they were often directly subsidized3 by the political parties themselves, and usually read by party members. Government would also subsidize such newspapers by offering more favorable postal rates. These newspapers would even contain party ticket ballots4 for readers to bring to polling stations—which at the time were often the paper’s headquarters or post office. Because early newspapers weren’t exactly cheap, early readers were mostly literate, property-owning men.

In the 1830s a medical student by the name of Benjamin Day5 had the idea that he could sell more papers by decreasing their cost, and increasing the price of advertising—given that the advertising would now be reaching many more eyeballs. Thus, The New York Sun—the first penny newspaper—was born, and with it, the goal of non-partisan reporting. It became more profitable to offer papers that would appeal to a broader audience, including the working class.

In 1841, Horace Greeley founded The New York Tribune, which was the first to separate opinion from news6 and place them in distinct, dedicated sections. Greeley used his own column to advocate for such things as abolition and labor rights. That’s how the op-ed tradition was born (though the term wouldn’t be coined until 1970 by The New York Times).

A growing number of journalists argue that the problem isn’t that writers have a bias, but rather that they are not upfront about it.

At that time, there was also a shift in who was writing copy. Originally most reporting was done by printers, postmasters, politicians, lawyers, clergy, pamphleteers, businessmen, as well as working-class voices representing their labor movements.7 Over time, journalism became more of a profession of its own—and with that came more professional practices such as the adoption of formal codes of ethics. With the founding of associations such as the Missouri Press Association in 1867, and journalism schools such as Missouri School of Journalism—the oldest in the world—founded in 1908, journalism became a true profession. The now-famous Columbia University school of journalism, a graduate-only program, was first proposed by Joseph Pulitzer in 1892, though it took twenty more years for it to be realized in 1912. Journalistic prizes, professional conferences, and the like helped legitimize journalism and make it a field in which quality was valued. The rise of objective journalism can be traced back to the 1920s8 and was in large part due to this cultivation.

Yet it wasn’t until the mid-20th century that journalistic objectivity or neutrality really came into play, particularly in the 1950s when The New York Times became the so-called “paper of record” and ABC, CBS, and NBC emerged as the only three television networks available nation-wide. The Fairness Doctrine9 (1949–1987), introduced by the FCC, required broadcasters to not only cover controversial issues of public importance, but also to present opposing viewpoints on such issues.

Today, of course, there’s a lot more variety in the media outlets available, so one could argue—as some have—that such an approach is no longer necessary. There’s no balance required because readers always have the option to go elsewhere, and with declining cost of entry into media due to the proliferation of the Internet, just about any niche can and will be served. Bezos’s own shift might strengthen brand loyalty among those who align with the new editorial stance, rather than chase an increasingly fragmented audience. Further, dropping the pretense of neutrality would allow more transparency about the media outlets’ respective perspectives. A growing number of journalists argue that the problem isn’t that writers have a bias, but rather that they are not upfront about it. Radical transparency, they argue, would solve that problem.

These are fair arguments.

As Hunter S. Thompson once said, “With the possible exception of things like box scores, race results, and stock market tabulations, there is no such thing as Objective Journalism. The phrase itself is a pompous contradiction in terms.”

However, I worry that this shift toward purely partisan media will further entrench us into ideological bunkers, where we only consume content that reinforces existing beliefs. So few shared frameworks or common cultural touchstones still stand today.

Can we find opposing views elsewhere on our own? Yes, of course. Some people will, but many won’t. Regardless, there’s something intrinsically valuable about encountering them in a shared space, where ideas engage, clash, and challenge one another directly. We can read the same stories and have a shared reference point, even if we disagree. Without that, the media landscape morphs into a series of self-reinforcing silos—less a marketplace of ideas, and more a collection of ideological vending machines, each dispensing only what its audience already wants to consume. What reinforces this further is that the increasingly segregated media landscape we find ourselves in today more often than not demands ideological purity, and thus has likely led toward even greater overall polarization.

However, even if we cannot separate ourselves from our biases altogether, should we not strive for more neutral language in how we report events? Some argue that there’s a moral imperative not to be neutral, for example when it comes to violent attacks or brutal regimes—whether it’s the January 6 Capitol assault, the human rights violations by the Taliban in Afghanistan, Nazi Germany, or modern-day Iran. At the same time, as writer Roy Peter Clark analyzes for Nieman,10 terms such as “boasted,” “storm,” and “attempted coup” use loaded, interpretive, vivid language that does far more than report the news: it plants within the reader a moralistic evaluation of what had transpired. Some will call it responsible journalism, others, well … the opposite. Clark cites S.I. Hayakawa’s book, “Language in Thought and Action,” where he argued for the importance of neutral reporting. Hayakawa saw it as the “antidote to the kind of vicious propaganda promulgated by the Nazis.” When the facts are presented as they are, without judgment of something being “bad” or “good”—readers can discern for themselves, rather than being manipulated into particular thought.

The press was meant to persuade, not necessarily to inform in an objective sense.

An argument can be made that journalists can remain objective by attempting, in good faith, to describe reality as it is—without taking a particular political side or having an agenda. That journalists won’t just describe the different viewpoints that exist on, say, vaccines, but rather investigate, gathering evidence to figure out whether they work or not—which would naturally lead to an opinion, whereas a truly “neutral” journalist wouldn’t express any conclusions. Of course, a biased journalist would start with their conclusion and then adjust their reporting to fit it.

A research paper by Katherine Fink and Michael Schudson, published in 2014 in the journal Journalism called “The Rise of Contextual Journalism, 1950s–2000s,”11 found that on the front pages of The New York Times, The Washington Post, and the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, conventional straight-news reports declined from 80–90 percent in 1955 to about 50 percent in 2003. Simultaneously, contextual reporting—stories providing analyses—increased from under 10 percent to about 40 percent during the same period. That is reflected in the increasingly authoritative attitude by journalists toward their making sense of the facts—something that we’ve seen a lot of pushback against in the last five years as trust in media has dropped to a historic low, with Gallup’s 2024 survey12 showing that only 31 percent of Americans express “a great deal” or “a fair amount” of confidence that the media reports the news fully, accurately, and fairly.

As activist journalism has resurged in recent years, the fact-checking process has also been notably cut from editorial budget lines. When I first started out in journalism, in the mid 2000s, it was common to have fact-checkers on staff at most major papers. These days, it’s a rarity, as that responsibility has been relegated to the writers themselves as a cost-cutting measure.

That change reflects history. Early newspapers were not only filled with partisanship and sensationalism, but the editorial standards were so loose that hearsay and rumors were common. Fact-checking was introduced13 as papers began to compete more for credibility. Offering accuracy was a way to win over readers’ trust.

In 1913, Ralph Pulitzer (son of Joseph Pulitzer) and Isaac White, through The New York World, established a “Bureau of Accuracy and Fair Play,”14 which tracked errors and repeat offenders. Its mission was to “correct carelessness and to stamp out fakes and fakers.”

TIME magazine was one of the first formal fact-checking15 departments, starting in the 1920s. Nancy Ford was the company’s first fact-checker and the New York Public Library served as Ford’s main source of information. Their staff would be dedicated to verifying names, dates, quotes, and claims. This also protected the publication from libel lawsuits. Around 1927, The New Yorker continued this tradition, and by so doing, established a reputation for meticulous fact-checking.

Journalism schools played a significant role in developing codes of ethics and standards, as well as instilling in students a sense of rigor toward research and verification. Major newspapers such as The Washington Post and The New York Times developed their own internal standards for source corroboration and editorial review.

In more recent years, however, fact-checkers have acquired a bad name with the public. As a way of countering the rise of misinformation and disinformation (two new, and to many people— loaded—terms), organizations such as Snopes, FactCheck.org, PolitiFact, and others emerged. These organizations are nearly all members of Poynter’s International Fact-Checking Network,16 which is funded by George Soros’s Open Society Foundations, Google, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the National Endowment for Democracy, eBay’s Omidyar Network, and other similar for and not-for-profit organizations.

Many readers found that these organizations went beyond merely checking information for accuracy— and like the fact-checkers in newsrooms—steered into murky waters of opinion and bias, which had an impact on their credibility. One notable example, in 2013, PolitiFact named President Obama’s statement “If you like your health care plan, you can keep it” as its Lie of the Year in 2013, only to rate the same claim as “half true” in 2008.

Fact-checking was introduced as papers began to compete more for credibility. Offering accuracy was a way to win over readers’ trust.

Snopes faced allegations from the political right of more harshly scrutinizing conservative claims, sometimes rating them “mostly false” simply because of technicalities, while using kid gloves for liberal ones. FactCheck.org was accused of similar bias, scrutinizing one party over another during election cycles. All of these organizations have been accused of making their fact-checking dependant on interpretation (which introduced ideological framing) rather than pure factual disputes.

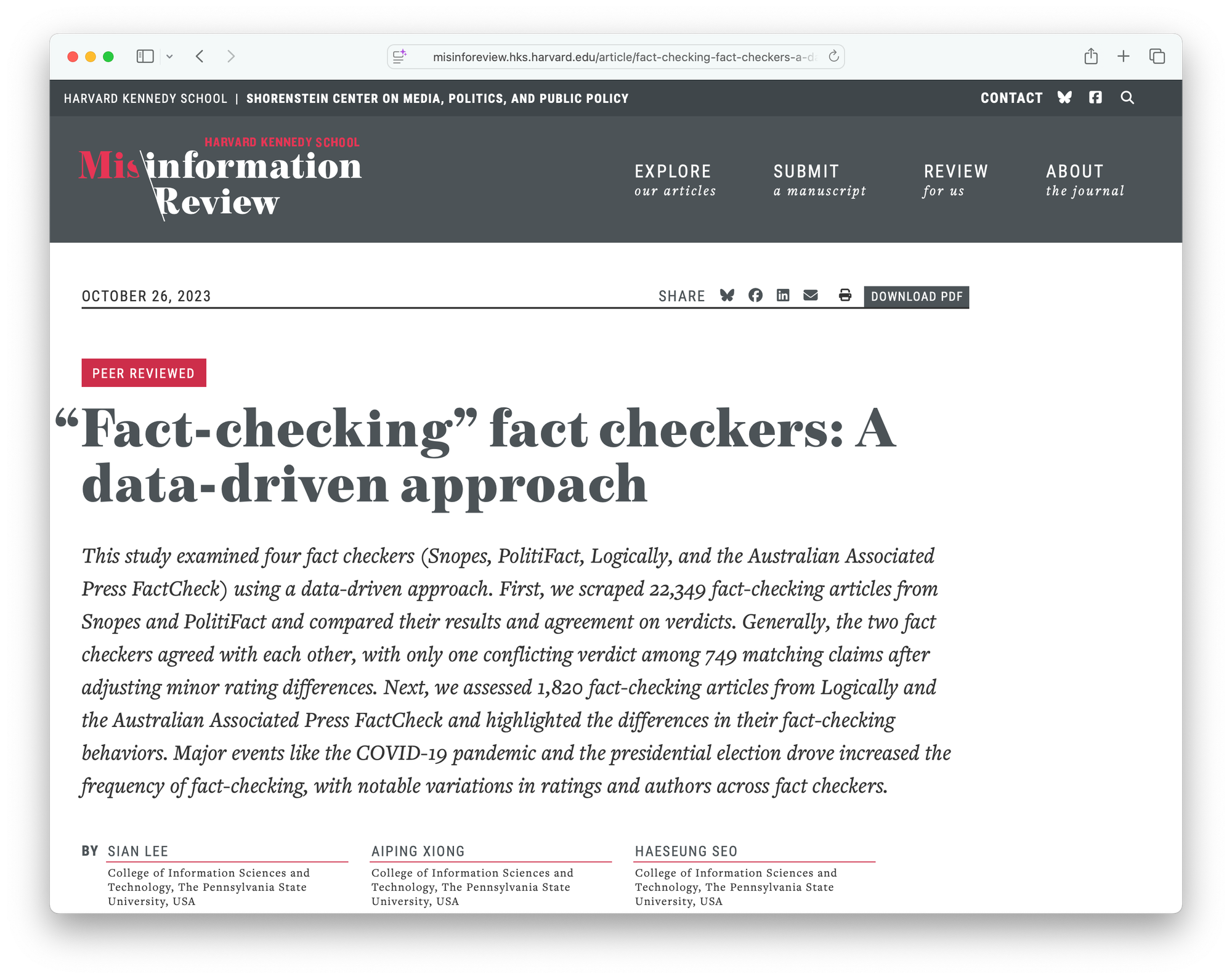

A study published in Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review17 titled “Fact-checking Fact Checkers: A Data-Driven Approach” analyzed the practices of four fact-checking organizations— Snopes, PolitiFact, Logically, and the Australian Associated Press (AAP). It found that Snopes and PolitiFact agreed on only 69.6 percent of similar or identical claims, often due to subtle variations in interpretation. The organizations also differed in their focus: PolitiFact and AAP prioritized false claims, while Snopes and Logically verified true ones. Fact-checking activity spiked during major events like COVID-19 and the U.S. election. The study also suggests that there’s a lack of transparency as to which claims fact-checkers investigate.

There’s also little transparency around who these fact-checkers are—or how they arrive at their conclusions. Certain outlets are routinely treated as the gold standard for verification, yet even reputable publications such as The New York Times and The Washington Post have published inaccuracies. So, is this kind of circular sourcing really the most reliable way to determine what’s true?

In TIME’s 25th anniversary in 1948, its editors wrote about the complexity of fact-checking:

All the facts relevant to more complex events … are infinite; they can’t be assembled and could not be understood if they were. The shortest or the longest news story is the result of selection. The selection is not, and cannot be, “scientific” or “objective.” It is made by human beings who bring to the job their own personal experience and education, their own values. They make statements about facts. Those statements, invariably involve ideas.18

They noted that all journalists are in the business of selecting facts:

The myth, or fad, of “objectivity” tends to conceal the selection to kid the reader into a belief that he is being informed by an agency above human frailty or human interest.

And ultimately, that’s the enduring challenge—not just of objective reporting, but of fact-checking itself.

Today, we are saturated with voices. Not only from traditional newsrooms, but from social media feeds, podcasts, and personal Substacks. Everyone is publishing. And everyone’s got an opinion.

Broken trust doesn’t just erode journalism—it fractures our very foundation for shared reality.

However, the abundance of opinion makes our commitment to striving toward intellectual honesty even more urgent. Just because objectivity in its purest form is unattainable doesn’t mean we should surrender the ideal altogether. We can still pursue fairness, evidence-based truth, transparency, and rigor, knowing all human enterprises are subject to bias and error—and so are AI implementations because they’ve been created by humans. And the same should hold true for a commitment to foster common spaces for disagreement.

Broken trust doesn’t just erode journalism—it fractures our very foundation for shared reality. And without that, truth itself becomes harder to recognize, let alone agree upon.