The Best of Times and the Worst of Times

That memorable opening of Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities reads …

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way—in short, the period was so far like the present period that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.

His oft-quoted comparison of Revolutionary France to Dickens’ own Victorian England could, in fact, be applied to any times. Why? Because, when examining the wealth and health of nations, the real questions should be: When? Where? For Whom? By Which Criteria? And those questions apply not only to cities, or to individuals, but to other aggregations, be they ethnic, religious, racial, economic, social, sexual, or even civilizational.

As the management guru Peter Drucker put it, “The most serious mistakes are not being made as a result of wrong answers. The truly dangerous thinking is asking the wrong questions.” Indeed, asking about the health and wealth of nations may well turn out to be a category error—the assigning to something a quality or action that should properly be assigned to things only of another category.

The study of the health and wealth of nations is, in reality, a story of Time, Space, and Energy, and yes, to echo Rod Serling’s introduction to the classic Twilight Zone television series, Mind. Of these, Mind is, was, and always will be the critical factor. Not only our bodies, but our minds, our similarities and our differences, whether individual or aggregated, our health and wealth are but the products of natural and cultural selection working in space and over time.

As humankind has harnessed increasing amounts of energy, that energy has been transformed and used to power the myriad manifestations of societal complexity such as art, music, architecture, economics, law, warfare, religion, institutions, sports, and even the various and diverse means and methods of sexual pleasure and reproductive control that distinguish our species. From control over fire and making tools in the Stone Age to nuclear-powered submarines carrying thermonuclear missiles, increasing control over increasing amounts of energy has given us increasing control over the natural world in which we arose, and the cultural world that we have created.

Time … When?

As long as our species has been around, we’ve wondered where we came from, how we got here, and where we are going. The earliest answers came from folklore, then religion, mythology (which was often someone else’s religion), philosophy, history, and eventually science. At each stage there have been three major answers—simply stated, the health, wealth, quality of life, technology, knowledge, and population of societies have kept increasing, or, inversely, that all those good things have been in decline (the “rise and fall of…”), or that they have all been locked in a perpetual endless cycle of better-worse-better-worse.

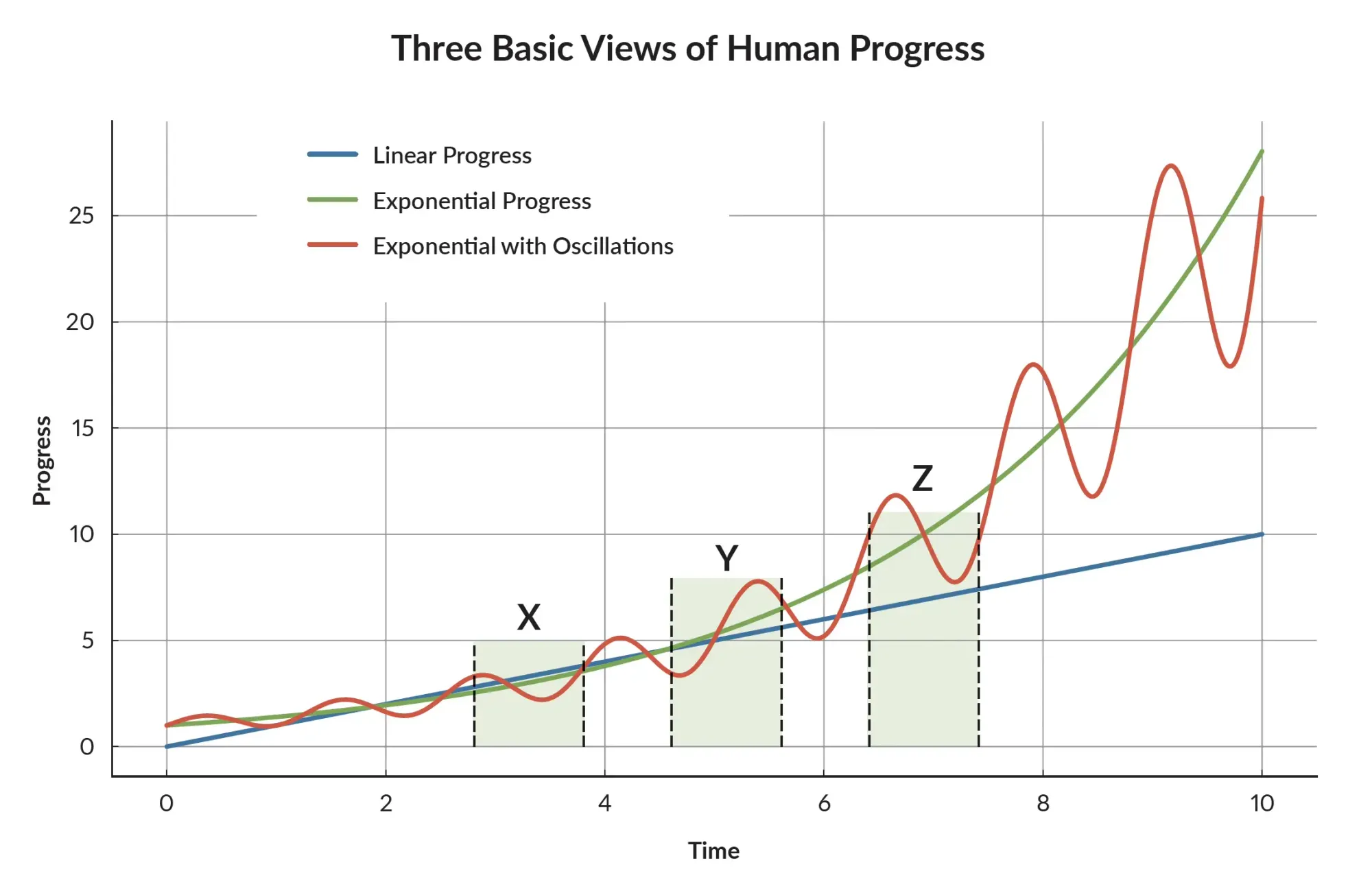

When the theory of evolution first took hold, not only of the sciences but of history and philosophy as well, the assumption was one of uniform linear growth from simple to more complex, with some groups (always the thinker’s own) going a bit faster and climbing up a bit higher (or sometimes a lot faster and higher), than the others. [Blue Line]. Increased knowledge in archaeology, history, and especially economics and information science has led to a more sophisticated view that the general trend has not been simply linear and increasing uniformly at the same rate, but rather exponential and increasing at an ever-accelerating rate. In The Moral Arc,1 Michael Shermer has described how the ever-increasing replacement of revealed religion by reason and empiricism has powered that exponential takeoff. [Green Line].

We now know that there also have been downturns, severe ones, even Dark Ages (though the most famous one turns out not to have been as dark as was first argued by Age of Reason writers wanting to put down the Age of Faith). [Red Line]. Along that exponentially increasing trend some areas have progressed further and faster than others, but it’s not always been the same ones. Good times for one group in one place, can be very bad for another group living somewhere else. While Western Europe was in that “dark age,” Central Asia led the world in trade and economic development, medicine, the arts, philosophy, and the beginnings of science.2 Today it’s land of the “-stans” and home to the likes of the Taliban.

In Collapse,3 Jared Diamond has described how various societies, from Easter Island, Norse Greenland, and the Mayans to contemporary Haiti, Rwanda, and even Montana, did just that, usually from self-inflicted mental and cultural rigidity in the face of changing environmental conditions. Similarly, Eric Cline has argued that the various Eastern Mediterranean Bronze Age societies all tanked in 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed4 from a perfect storm of climate change leading to drought, leading to famine, leading to political, social, and economic upheaval, capped off by the invasions of those damned “Sea Peoples.” So really, the single red line in Figure 1 should actually be a series of red lines representing different areas and groups. And each of those lines could be further subdivided into several lines, each representing a specific aspect of society (law, technology, science, wealth, health), which have not all progressed at the same rate.

Humanity’s increasing ability to harness and control increasing amounts of energy is responsible for the evolution of increasingly larger groups.

With those caveats, and looking at the line segments marked X, Y, and Z in the figure, we can see how various thinkers could seize upon a particular segment or portion of a segment and argue for progress, regression, or perpetual cycling to derive and support their view. Fundamentalists of the Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) reject evolution, each in favor of their own interpretation of their specific holy book that, they believe, reveals all truth, now and forever. I recall one gospel preacher summarized their case for things going to Hell (which he meant literally) by posing the rhetorical question, “Evolution says man started off dumb and got smart. The Bible says man started off smart [Adam in the Garden of Eden] and got dumb. Look around. Which one do you believe?” For me, having retired and moved from one of the highest socioeconomic status (SES) and lowest crime rate ZIP Codes in California to its inverse, his view takes on far greater face validity here and now than it did then and there. But that’s what can happen when one generalizes from small samples of either time or space.

Space … Where?

Looking around the world one sees that nations vary greatly in their average health and wealth. The nations of the Global North (Europe, U.S., Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Japan) all score highly in both categories. The Least Developed Countries, which includes most of Africa, parts of Central and South America and Asia, do not. The Global South (parts of Asia and Central and South America) fall in between, with many, especially in Asia, moving quickly and impressively into Global North status. In some respects, China is even taking—or maybe retaking—the lead. However, conditions are hardly uniform within nations. You don’t even have to move as far as my earlier California example to see how different things can be. It’s only about 10 miles from Beverly Hills 90210 to Skid Row 90012, but they’re far more different from each other than either is like comparable SES ZIP Codes in other states or even locales in other countries. University towns like Berkeley, CA, and College Park, MD, look, act, and vote a lot more like each other than they do the surrounding county. That’s why today candidates for public office tailor their campaign messages to specific ZIP Codes.

Analyzing health and wealth by nations (or other aggregates such as races, even occupations) can be informative, it can also be misleading because it misses the within-group diversity when one looks at measures of central tendency (averages) such as GNI (gross national income) per capita, GDP (gross domestic product) per capita, and mortality and disease rates. Nonetheless, geographical location definitely has its effects on health and wealth. The fields of Epidemiology and Spatial Econometrics have sprung up to gauge them because they “carry” information often not “picked up” by other, more frequently studied, variables.

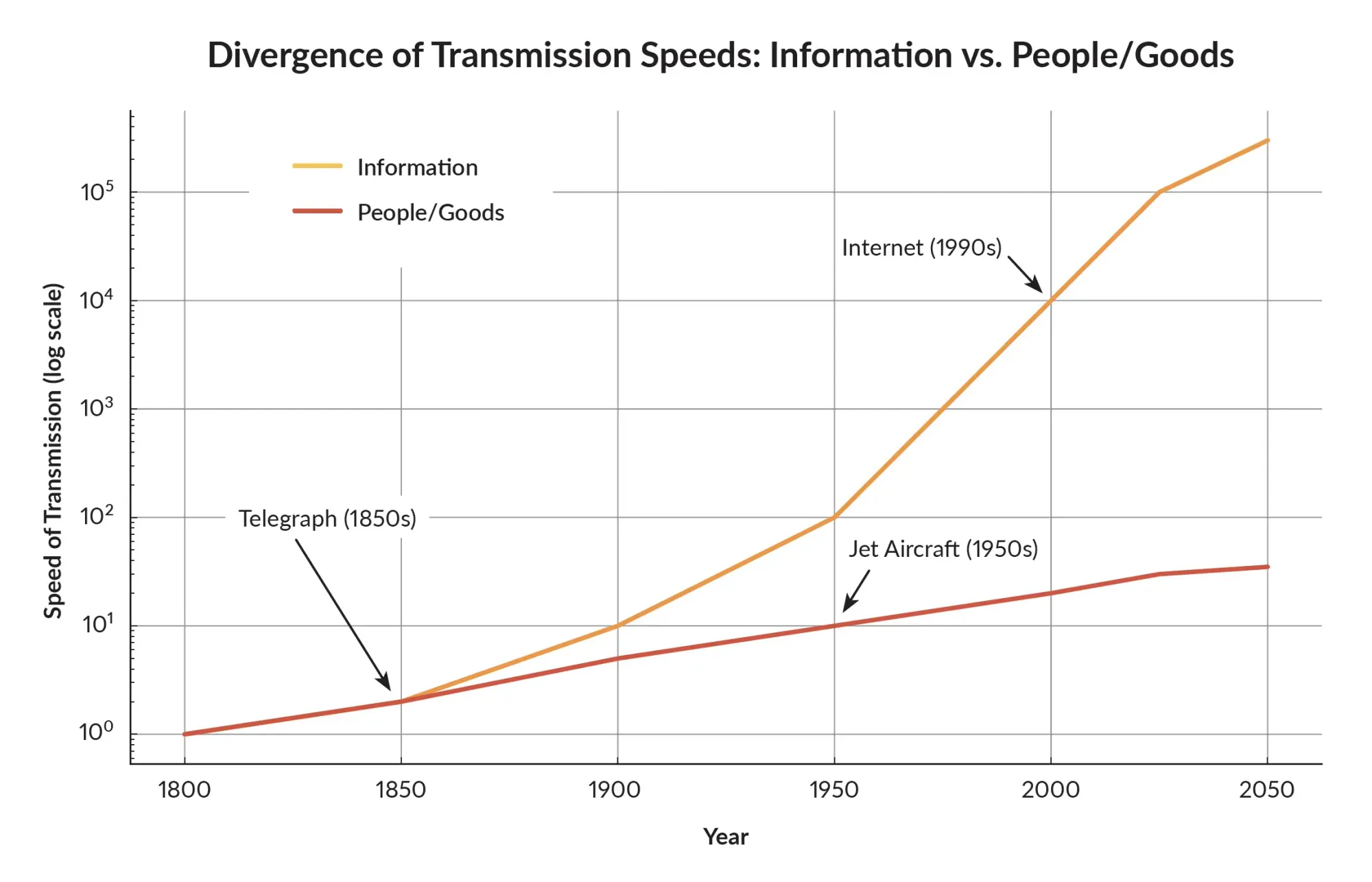

The Conquest of Space—by Speed

One of the major effects of the increase in the amount of energy we can control is that it has increased the rate at which we can transmit both information as well as goods and people. As shown in Figure 2, starting with the invention and large-scale deployment of the telegraph around 1850 we have been able to transmit massive amounts of information at increasingly faster speeds. (Granted, talking drums, smoke signals, and fire beacons on the Great Wall of China did allow for limited amounts of information to be transmitted faster than humans or goods could travel, but their effectiveness was very subject to weather conditions.) Today, goods and people can travel near the speed of sound (jet airliners) while information can move at near the speed of light (Internet). Faster transmission speed of information also has other benefits, including lesser probability of disruption or loss of information, faster recovery in case of disruption, much greater facility for encryption, and even practical benefits such as near immunity from weather conditions.

Humanity’s increasing ability to harness and control increasing amounts of energy is responsible for the evolution of increasingly larger groups—from bands to tribes to chieftainships, nations, and even empires—in terms of population, area, social complexity, technology, wealth, health, as well as in increasing genetic and cultural diversity. The very formation of states (and their dissolution) is a function of our ability to “shrink” space through greater speed.

Equality and Inequality … for Whom?

In comparing the wealth of nations, statistics such as GNI per capita and GDP per capita are informative. Since they are averages, however, they only tell part of the story—and sometimes misleadingly so given that a few extreme values can have disproportionate effects. The Antebellum South had a very high GNI and GDP, and high per capita income. But how was it distributed? The bulk of it went to the benefit of the relatively few White families who owned the big plantations and lived in those Gone With the Wind–type, white-columned mansions; relatively little went to the Black slaves who made up the bulk of the plantation population and did almost all the work that created all that wealth. And slaves on those large plantations were, in many cases, materially better off than either just-off-the-boat immigrant workers up North or even poor White rural communities in upland parts of the South.5 It’s hard to say what dollar value you can place on freedom, but suffice it to say, the Underground Railroad ran only one way and there were no immigrants or hardscrabble country folk who signed up to be slaves in order to enjoy those greater material benefits.

To determine what’s really going on, one needs to look at both the average and the variance of any distribution. Particularly useful, though not often reported, is a statistic called the Gini Coefficient. It measures the extent to which the distribution of income or wealth deviates from being perfectly equal, and ranges from 0 (where we each enjoy our equal share) to 1 (where one person has it all).

Increased speed at which goods and services and especially information travel has also affected the distribution of income, wealth, and even health—and to the benefit of (certain) individuals and the detriment of nation-states. When I was growing up in the 1950s, there was a benefit just in living in the United States, especially in being close to New York City. It took a long time to get goods from other areas, even more from other countries, while engaging services was just out of the question. You mostly bought locally and you definitely hired locally. There was no alternative, other than maybe sending your measurements to a tailor in Hong Kong to make a suit for much less than the tailor downtown. (But just maybe that downtown tailor took your measurements and, unbeknownst to you, sent them to the tailor in Hong Kong, and apologized for the “unexpected” delay.)

The result was that tailors, farmers, teachers, and other occupations enjoyed a monetary benefit just by being in the U.S. and especially in being near a major city. They could earn more in raw dollars and enjoy a better quality of life than a lawyer or a professor in India. With increased transmission speeds, that’s no longer the case. You can send your measurements online straight to that Hong Kong tailor (better yet, many of them go “on tour” to major American and European cities and measure their clientele in person), you can get food grown more cheaply in another country, frozen, and sent to the U.S., and you can even take your music lessons on Zoom from a virtuoso in Milan or Vienna—or Merry Old England or Melbourne, Australia (both of which I’ve done).

Increased speed at which goods and services and especially information travel has also affected the distribution of income, wealth, and even health.

The deck has been reshuffled and the effects of space diminished, and in some cases, to zero. There are winners and there are losers—even if only relatively versus others or versus their previous position (or what they remember as being their previous position). The winners tell funny stories and the losers say, “Deal the cards!” When Francis Fukuyama published The End of History and the Last Man6 in 1992 it seemed as if the Global Economy was putting nation-states on the endangered list. Today things look very different as those who see themselves as the losers have voted out governments of the Left (Germany), the Right (UK), and the Center (the Netherlands), while in the U.S. they voted out the Left (2016), the Right (2020), and then the Left again (2024). What’s the method that unites this madness? These irate voters are not ideological, they’re just pissed off because they feel, and not without some justification, globalization has left them to rot like roadkill on the information highway. And the feeling is even stronger when they see immigrants or some other nation doing better.

Validity … by Which Criteria?

Following Lord Kelvin, science, economics, and increasingly even history, have followed the axiom that when you can measure something and express it in numbers, then you really know what you’re talking about. Simply stated—numbers don’t lie. But, as we’ve seen, they can deceive and mislead. Do those numbers truly measure what we think they mean? Public opinion analyst Daniel Yankelovich described what he called “The McNamara Fallacy” after Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, who was convinced the U.S. was winning the Vietnam War—at least according to the numbers on his spreadsheets. It involves measuring what you can measure and disregarding what you can’t because, well, it’s either unimportant or simply doesn’t exist.

Along those lines, many have argued that aggregated output measures like GNI and GDP should be replaced, or at the least supplemented, by measures of Quality of Life to capture those things that are impossible, or at least very difficult, to measure. And that’s precisely the problem with them. How do you measure them? Which ones do you include? Does automobile air conditioning increase the quality of life through providing greater comfort? Or does it decrease it by encouraging more use of single-passenger automobiles and thereby producing more air pollution?

Simply stated, the good stuff all tends to gather together and so does the bad.

Some scholars argue that even the collapses described by Diamond and by Cline were neither so deep7 nor so wide.8 If defined as the complete end of a civilization or culture and its political systems, they submit, such collapses simply don’t happen, especially for huge areas over (more or less) the same time. Rather than catastrophic collapse, they argue, we should look at the resilience of peoples and cultures, which is often best seen in the persistence of languages, religions, and mores—to which I would add, ways of thinking about things among indigenous peoples or subgroups within industrial and information age nations.

Mind … What Drives the Health and Wealth of Nations?

Despite all the above caveats, gauging the health and wealth of nations need not lead into an obscurantist quagmire. One mitigating factor is multicollinearity, where what are assumed to be independent variables are all correlated with each other. Simply stated, the good stuff all tends to gather together and so does the bad. This often, though not always, means that those seemingly independent measures are in fact all dependent on some other variable, at least to some degree. And this is true for most of the measures of health and wealth, even the qualitative ones. But why?

Among the factors proposed as driving higher wealth and health are the purely physical (living on top of a sea of oil, especially in a desert and so having a low population) and the institutional, economic, attitudinal, cultural, mental—chose your preferred moniker for the rubric. The nominees include: rule of law, economic freedom (compare bustling South Korea with the “locked down” North), education, literacy, and human capital—the product of cognitive ability and educational experience, especially among the talented top 5 percent. Following Karl Popper’s9 terminology I would supplement these with the three pillars of an open society:

- the scientific method as the best way to determine what exists and how things work,

- some form of a market economy as opposed to one that is centrally planned or traditional (though it may benefit from implementing a level of social welfare safety nets), and

- some form of representative government.

What these all share is that they are negative feedback loops. They may work more slowly than positively driven command systems, but they avoid the latter’s susceptibility to headlong plunges into superstitious, economic, military, or social disaster.

Far and away the most controversial of these proposed causes is cognitive ability (though the others are not without their own disputations, some quite heated). But, for present purposes, it need not be. Whether measured by IQ, school achievement, cognitive reaction time, whether for an individual or a group, it results in a test score represented by a number (just like BMI—Body Mass Index). That number can be understood as representing the construct of intellectual ability, which I’ll call IQa (ability) that is the product of heredity and environment. Alternatively, suppose it can be understood in terms of another construct that I’ll call IQm (method). Rather than the psychometrics of Francis Galton and Alfred Binet, the latter is derived from the art of method acting pioneered by Konstantin Stanislavski and Lee Strasberg, and expertly practiced by the likes of Marlon Brando, Meryl Streep, Al Pacino, Forest Whitaker, and Joaquin Phoenix.10

So assume IQm measures the degree to which one has immersed oneself in the thinking and values of the information age global economy—logic, law abidingness, curiosity, conscientiousness, delay of gratification, and trust, all with a healthy dose of skepticism and critical reasoning, which are essentially the same characteristics associated with higher IQa scores.

The good news? Allow either IQa or IQm, whatever their cause, or more likely causes transacting over the course of development, or any yet-to-be-determined complex fusion of them, to operate in an open society and you have the formula for increasing the health and wealth of any nation.