The Case for a Free & Prosperous Society

In July 1778, during the American War of Independence from Great Britain, then-American ambassador Benjamin Franklin received a letter from a British official using the alias Charles de Weissenstein, hopeful that he would agree to begin negotiations for a peace settlement.

Franklin wrote a lengthy reply but never sent the letter, stating, “Your Parliament never had the right to govern us, and your King has forfeited that right through his bloody tyranny.” Full independence was Franklin’s goal, but he took the time to outline his philosophy of an “independent state.” He wrote, “We purpose, if possible, to live in peace with all mankind.” He saw no need for “fleets or standing armies,” believing that “our militias … are sufficient to defend our lands from invasion.” Franklin argued there was no need to expand beyond a “small civil government” with “no offices of profit, nor any sinecures or useless appointments, so common in ancient and corrupted states.” He concluded, “We can govern ourselves for a year with the sums you pay in a single department,” summing up the role of the state in one sentence:

A virtuous and laborious [industrious] people may be cheaply governed.1

Today’s federal government is a far cry from Franklin’s vision of a laissez-faire state. As Thomas Jefferson presciently observed, “The natural progress of things is for liberty to yield, and government to gain ground.”2 The public sector has ballooned, we have an active-duty military of 1.3 million soldiers and a $1 trillion defense budget, a burgeoning national debt of over $36 trillion, around 100 million people receiving some form of government assistance, the cost of living on a permanent rise, and a bloated bureaucracy.

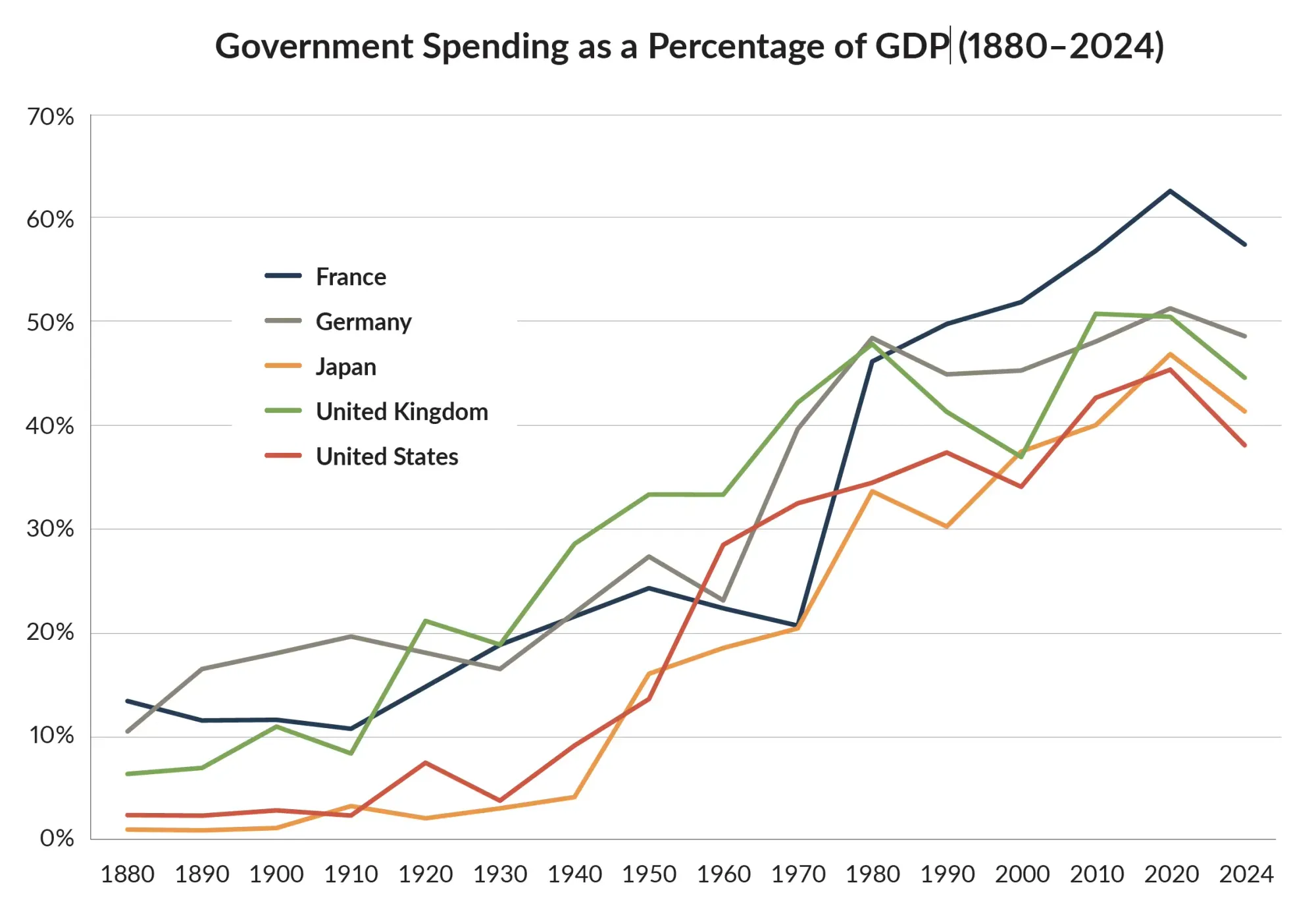

Government has gotten bigger, not stronger, and can now only do three things effectively—tax, wage war, and inflate the currency. As management guru Peter Drucker declared, the state has become a “swollen monstrosity,” adding, “Indeed, government is sick—and just at a time when we need a strong, healthy, and vigorous government.”3 And that was in 1969! Figure 1 illustrates the dramatic rise in various governments around the world, not just the United States.

Perhaps the decline in government since 2020 suggests the law of diminishing returns has finally caught up with state power. Certainly the rise of the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) to root out waste and unnecessary public spending in the United States, as well as the implementation of fiscal austerity in Argentina and elsewhere, are a signal that an about-face in state activity—at least in some parts of the world—may be coming. But is that a good thing?

In his classic 1850 work The Law, the French economist Frédéric Bastiat argues that the sole purpose of the state “is the collective organization of individual right to lawful defense,” adding “Each of us has a natural right—from God—to defend his person, his liberty, and his property,” and to achieve this goal, “a group of men have the right to organize and support a common force to protect these rights constantly.”4 Over a century later the Nobel prize-winning economist Milton Friedman elaborated on the principle:

The scope of government must be limited. Its major function must be to protect our freedom both from the enemies outside our gates and from our fellow-citizens: to preserve law and order, to enforce private contracts, to foster competitive markets. Beyond this major function, government may enable us to accomplish jointly what we would find difficult or expensive to accomplish severally. … The role of government just considered is to do something that the market cannot do for itself.5

This is another articulation of Benjamin Franklin’s vision of government as “cheaper and better.” Franklin was an optimist. He envisioned that “America will, with God’s blessing, become a great and happy country.” If he were alive today, I believe he would marvel at our high standard of living, our technological advances and gadgets, the dynamic stock market, and an American dream that still inspires millions of young people. His motto would be: “Don’t sell America short. We can overcome our blunders and achieve new heights.”

Government has gotten bigger, not stronger, and can now only do three things effectively—tax, wage war, and inflate the currency.

Franklin was a devotee of Scottish philosopher Adam Smith and his “system of natural liberty,” as developed in his magnum opus, The Wealth of Nations. The two-volume work was published a few months before Thomas Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence in 1776. Smith’s book was a declaration of economic independence. Franklin’s writings mirrored Smith’s philosophy of maximum liberty, as in his declaration “Laissez nous faire” (“Let us alone”) and “Pas trop gouverner” (“Not to govern too strictly”). He endorsed Smith’s policy of free trade that resonates with current debates over taxes and tariffs:

To lay duties on a commodity exported which our friends want is a knavish attempt to get something for nothing. The statesman who first invented it had the genius of a pickpocket. Most of the statutes, acts, edicts, and placards of parliaments, princes and states, for regulating, directing, and restraining of trade have either political blunders or jobs obtained by artful men for private advantage under the pretence of public good. In general the more free and unrestrained commerce is, the more it flourishes. No nation was ever ruined by trade.6

Adam Smith outlined his basic thesis as follows: “Every man, as long as he does not violate the laws of justice, is free to pursue his own interest his own way, and to bring both his industry and capital into competition with those of any other man, or order of men.”7 Simple, really: maximize freedom within the restraints of the law and robust competition.

The more economic freedom a nation enjoys, the higher its standard of living.

If heads of state followed Smith’s model, what would be the result? Smith had high hopes: “universal opulence which extends itself to the lowest ranks of the people.”8 As Smith proclaimed in 1755 (from notes transcribed by his contemporary popularizer Dugald Stewart): “Little else is required to carry a state to highest degree of opulence from the lowest barbarism, but peace, easy taxes, and a tolerable administration of justice.”9

What is the optimal size of government?

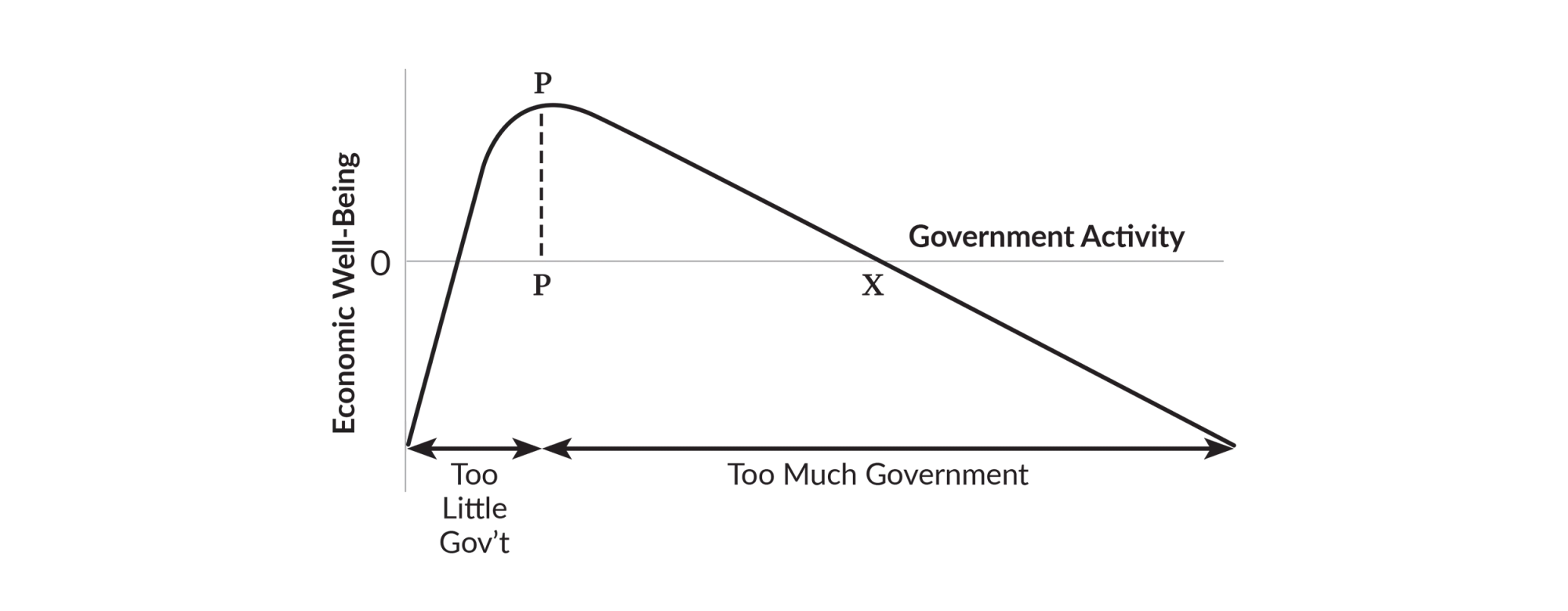

In 1996, economist Richard Rahn created the Rahn Curve (Figure 2) to illustrate the optimal size of government. The model suggests that the ideal size of government should be between 15 and 25 percent of a nation’s (or subdivisions thereof) Gross Domestic Product. The Rahn Curve offers a clear and straightforward way to understand the trade-offs between government size and economic growth. It highlights that both extremes—too little government (underfunding public goods) and too much government (overburdening the economy)—can negatively affect growth. It is important to note that the quality and efficiency of spending matter just as much as the quantity. For example, one country might spend efficiently on infrastructure, while another wastes funds on corruption or unproductive programs—yet both could have the same “size” on the curve.

As an economist, I frequently think about the question of optimal government size. Consistent with the Smith “system of natural liberty” and one that promises “universal opulence” for all citizens, I posit there are five key principles of an optimal government, which I develop in more detail in my recent book, Economic Logic:

- A strong but small government financed by a simple flat tax system based on the benefit principle (if you benefit, you pay, or the user-pay principle).

- A tolerable administration of justice, rule of law, and independent judiciary (that minimizes corruption and fraud).

- Free trade, globalization, and liberal immigration.

- Sound money (minimum price inflation) due to a stable monetary system.

- Business regulations that encourage entrepreneurship and risk taking, while reducing environmental damage to the ecosystem.

Why Economic Freedom is Beneficial

In the mid-1980s, Michael Walker, president of the Fraser Institute in Vancouver, Canada, organized a group of free-market economists, including Milton and Rose Friedman, to measure and qualify economic freedom based on five broad criteria:

- Size of government and tax policy.

- Legal structure and security of property rights.

- Access to sound money.

- Freedom to trade internationally.

- Regulation of credit, labor, and business.

The result was the publication in 1996 of the book Economic Freedom Around the World, which has been published every year since.10 (The Heritage Foundation also began publishing its own Economic Freedom Index at the same time.11) Its purpose was to quantify economic progress (or regress) in order to identify the most important factors to accentuate (or attenuate). The major findings of the Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom of the World 2004 Annual Report confirm Adam Smith’s model:

This research has found that economic freedom is positively correlated with per-capita income, economic growth, greater life expectancy, lower child mortality, the development of democratic institutions, civil and political freedom, and other desirable social and economic outcomes.12

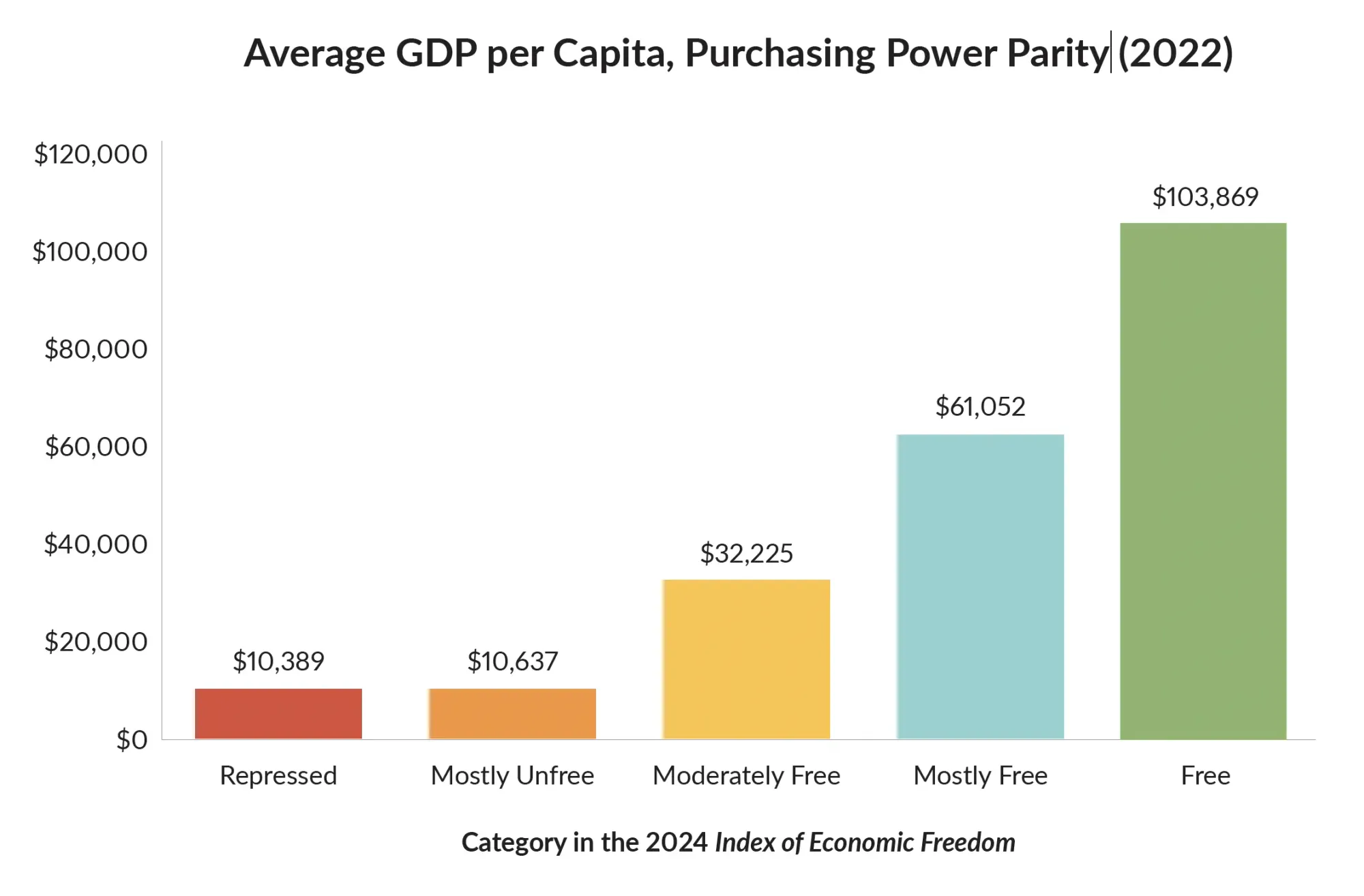

Figure 3 demonstrates how the more economic freedom a nation enjoys, the higher its standard of living.

In response to those critics of capitalism who claim that its rapaciousness harms the environment, the Fraser Institute also provides evidence that countries with higher levels of economic freedom also enjoy a cleaner, more sustainable environment.

According to the authors of the 2024 report, James Gwartney and Robert Lawson, most important of the five criteria listed above is a proper legal structure. Securing property rights, enforcing contracts, and consistently applying the rule of law are essential if a country is going to grow and achieve a high level of prosperity for all its citizens. They point to a number of countries that lack an independent judiciary and sound legal system, and as a consequence suffer from corruption and bribery, insecure property rights, poorly enforced contracts, and inconsistent regulatory environment, particularly those in Latin America, Africa, and the Middle East. Gwartney and Lawson conclude that, “The enormous benefits of the market network—gains from trade, specialization, expansion of the market, and mass production techniques— cannot be achieved without a sound legal system.”13

Best Policies in a Free Society

What then, specifically, are the best policies government should adopt in order to foster a free society?

Inexpensive government can be achieved by following Milton Friedman’s rule: Government should limit itself to doing only those things that private enterprise would have a hard time doing by itself, such as building public roads, parks, government buildings, ports, and other infrastructure in cities and towns, and using competitive bidding by private contractors to keep costs down.

It is not necessary for government to provide garbage collection, education, welfare, retirement accounts, medical services, or recreational facilities, since they can be developed and paid for by private businesses, individuals, families, churches, and charitable institutions. Overly generous and permanent welfare and costly educational services paid for by government are a major reason for bloated and unresponsive bureaucracies. Social Security and Medicare could be privatized and run more efficiently. The Singapore Medisave program provides an example of a well-run medical program that offers universal coverage and market-based health savings accounts at a fraction of the cost in the U.S.14

Peter Drucker wrote extensively about the benefits of the private sector, especially the large corporation, which he described as the “non-revolutionary representative social institution,” capable of providing more fulfilling employment, retirement, education, and medical insurance programs than the state.15 Israeli economist Shlomo Maital concurs, noting that:

The health and wealth of a large number of individual businesses—small, medium and large—determine the economic health and wealth of a nation. When they succeed, managers create wealth, income, and jobs for large numbers of people. … It is businesses that create wealth, not countries or governments. It is businesses that decide how well or how poorly off we are.16

Tax Policy: Applying the Benefit Principle

How should legitimate government services be paid for? Here the benefit principle applies—if you (or your business) benefit from government services such as defense, police, judicial system, transportation, etc., you should pay taxes estimated by how much you benefit. The more you benefit, the more you pay.

Toll roads and peak pricing are examples of the principle, since they are linked to use by drivers, and can mitigate the problem of traffic jams. More and more countries are instituting this pricing mechanism to ration expensive transportation systems.

For general services, the simplest approach is a flat tax, whether in the form of a sales tax, property tax, income tax, or a user fee. In general, a tax should rise only in proportion to the benefits provided. For example, a tourist tax might be appropriate as long as it is paying for tourist benefits. A tourist tax or sales tax to pay for a local sports arena, on the other hand, is inappropriate because it is a violation of the benefit principle. Sports and cultural facilities should be financed by the owners and the customers who actually attend the events—and thus benefit from them—not by the public taxpayer who may or may not benefit. By contrast, progressive or graduated taxes on income or wealth based on the faulty “ability to pay” principle should be avoided because of their complexity and potential abuse. As the nineteenth century British economist J.R. McCulloch explained:

The moment you abandon … the cardinal principle of exacting from all individuals the same proportion of their income or their property, you are at sea without rudder or compass, and there is no amount of injustice or folly you may not commit.17

Adopting Sound Money

The biggest challenge for a free society lies in the monetary sphere. What is the best monetary system to provide relatively stable prices and (near) full employment? It’s an elusive goal, easier said than done, and many books have been written on the subject. Since the United States went off the gold standard in 1971, the Federal Reserve has engaged in repeated episodes of easy money and tight money, which have only served to create unnecessary business cycles while providing little stability over time.

In the nineteenth century, the free-market solution was to adopt the gold and silver standard, where every currency was linked to a specified amount of gold (for large transactions) and silver (for smaller transactions). It worked fairly well until 1914, when World War I placed big demands on the economy and government. Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz noted, “The blind, undesigned and quasi-automatic workings of the gold standard turned out to produce a greater measure of predictability and regularity … than did deliberate and conscious control exercised within institutional arrangements intended to promote stability.”18

Free trade also enhances better foreign relations and reduces the chances of war.

The problem with the classical gold standard is that the gold-backed money supply increases only 1–2 percent a year. With real economic growth rising 3–4 percent, the result was price deflation. The best policy is to provide a stable monetary policy that is neither tight money nor easy money. A steady rise in the broad-based money supply that is equal to the long-term real economic growth rate, as advocated by Milton Friedman, is a better solution than the Federal Reserve’s manipulation of interest rates and piling up debt (called “quantitative easing”). Today’s gold advocates, such as Steve Forbes, recommend that the central bank also use the price of gold as a monetary target along with the money supply and interest rates, with the goal of keeping the price of gold relatively stable. Another proposal by Judy Shelton in her 2024 book Good as Gold is for the Treasury to issue gold-backed bonds, which would discourage the government from inflating the money supply. I recommend all three of these policies.

Free Trade and Foreign Relations

Free trade is another factor associated with free and prosperous nations. Using cost-benefit analysis, the historical evidence is overwhelming that the benefits (lower prices, greater choices, higher quality, and improved relations with other countries) exceed the costs (job losses and business failures in some industries). Trade agreements have generally proven to be beneficial, leading to lower tariffs and fewer restrictions on each side, resulting in increased trade, economic growth, and lower consumer prices. Free trade can create serious job displacement and business failures in certain sectors. However, labor is the most flexible of the factors of production—workers can be retrained and take other, hopefully better, occupations. Under free trade, unemployment is mostly transitory, and the rate is low.

Free trade also enhances better foreign relations and reduces the chances of war. While the Military Industrial Complex that President Dwight Eisenhower warned against is not only alive and well, but growing rapidly, commerce between countries reduces tensions. Again, as Benjamin Franklin reflected on the ideal foreign policy: “The system of America is commerce with all, and war with none.”

Business Regulations

Adam Smith describes the ideal model of economic laissez faire by creating a society without undue interference by the government. It is the “invisible hand” that checks unbridled greed and moderates the passions. A properly balanced free-market economy controlled by the rule of law and encouraged by a competitive environment would minimize—though not eliminate—fraud, negligence, and failure.

Excessive regulations and bureaucracy can stifle entrepreneurship and the economy. Countries differ significantly in how much time it takes to register a business, to get approval for a new drug, or for the local government to issue a building permit. There is great value in creating voluntary labor unions, employee ownership plans, and nonprofits offering products and services, including private companies that self-regulate their own industries (such as the Better Business Bureau and Consumer’s Union). Governments should make every effort to be transparent, set simple rules, and minimize interference in the marketplace.

Dealing With the Environment

This analysis would not be complete without a discussion of the environment and the well-being of the earth we inhabit. Environmental regulations are increasing, but are they appropriate? Environmentalists complain that unrelenting emphasis on economic growth under unfettered capitalism and big business leads inevitably to overuse and exploitation of resources, pollution, and ecological degradation. They also argue that free-market economists don’t take environmental issues and climate change seriously enough. In response, organizations such as the Property and Environment Research Center (PERC) have developed numerous programs in what founders Terry Anderson and Donald Leal call “free-market environmentalism.” They note that wealthy nations have a greater capability to reduce pollution and address the issues of climate change, and have created modern technologies and economic incentives to make the environment better and overcome “the tragedy of the commons.” As Albert O. Hirschman observed, “There is a tendency to blame capitalism for environmental damage, but now we find that in the socialist bloc the situation is much worse.”19

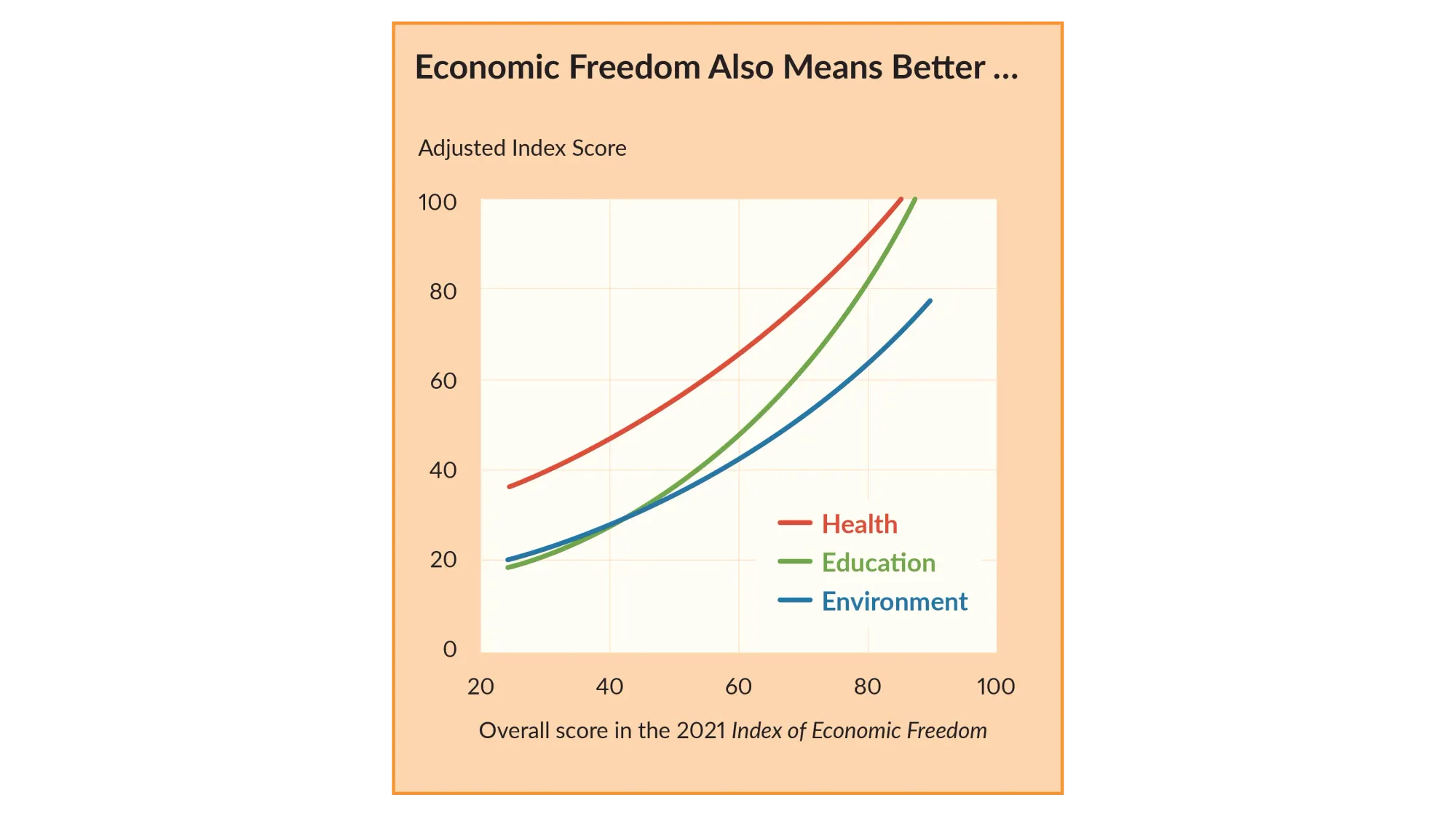

Indeed, the Heritage Foundation has documented how countries with greater economic freedom have less pollution and better environmental conditions, as well as higher levels of education and better overall health. See Figure 4.

Conclusion: freedom is still a dangerous word.

In this brief defense of the (libertarian) case for a free and prosperous society, I conclude, once again in concurrence with Adam Smith, that a nation which maximizes economic and political freedom will generate widespread prosperity that reaches even its poorest citizens. Perhaps Frédéric Bastiat said it best:

Look at the entire world. Which countries contain the most peaceful, the most moral and the happiest people? Those people are found in the countries where the law least interferes with private affairs; where government is least felt; where the individual has the greatest scope, and free opinion the greatest influence; where administrative powers are fewest and simplest; where taxes are lightest and most nearly equal, and popular discontent the least excited and least justifiable … where trade, assemblies, and associations are least restricted … [where] law or force is to be used for nothing except the administration of universal justice.20

Economic freedom is still on the defensive these days—suffering from assaults by both Democratic and Republican administrations— but through education and experience I remain confident that we can course correct back to these fundamental principles.