Covid Conspiracies and the Next Pandemic

While investigating Unidentified Anomalous Phenomena (UAP) for the UK Ministry of Defence, I was exposed to conspiracy theories that allege that the government is covering up proof of an alien presence. I’ve since become an occasional media commentator on conspiracy theories and have even been the subject of one myself, with some people claiming that I’m still secretly working for the government on the UAP issue. Most conspiracy theories are binary: we either did or didn’t go to the moon; Lee Harvey Oswald either did or didn’t act alone; 9/11 either was or wasn’t an inside job—and if it was an inside job, the choice is binary again: The Government Made It Happen or The Government Let It Happen.

The Covid pandemic generated multiple conspiracy theories, but the fact that most have been proven to be false shouldn’t lead people to conclude that what might be termed “the official narrative” about Covid is necessarily true in all aspects. It wasn’t.

A flawed “everyone’s at risk” narrative was promoted.

Covid wasn’t a “plandemic” orchestrated by nefarious Deep State players. Neither did the vaccines contain nanobots activated by 5G phone signals. But not everything we were told about Covid was correct: lockdowns and cloth masks didn’t have anywhere near the impact on slowing community spread or lowering mortality rates that was originally hoped for and subsequently claimed. Some studies now suggest the benefits were statistically insignificant. The vaccines didn’t stop transmission. And in one staggering admission—written by a New York Times journalist, no less!—a child was statistically more likely to die in a car accident on the way to school, than of Covid caught at school: “Severe versions of Covid, including long Covid, are extremely rare in children. For them, the virus resembles a typical flu. Children face more risk from car rides than Covid.”

A flawed “everyone’s at risk” narrative was promoted, in a situation where elderly people and others with comorbidities were vastly more likely to have serious health outcomes. The benefits of natural immunity were downplayed, and obesity as a risk factor was hardly discussed, perhaps because of politically correct sensitivities about fat-shaming. Partly, all this was because Covid was new, with key pieces of the puzzle unknown—especially in the early days of the pandemic. Later, it reflected the difficulty of interpreting statistics and analyzing data, especially where there were different ways of doing so, in different countries, or at different times. The debate over whether someone died of Covid (i.e., the virus killed them) or died with Covid (they died of some other cause and happened to be infected with the virus) is one example of this.

Obesity as a risk factor was hardly discussed, perhaps because of politically correct sensitivities about fat-shaming.

Nothing exemplifies the more nuanced nature of Covid conspiracy theories than the lab leak debate. Was Covid a case of zoonotic emergence, centered on a wet market in Wuhan, or an accident involving the Wuhan Institute of Virology? According to previous assessments by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, some parts of the U.S. Intelligence community favored one theory, some favored the other, while some were undecided. Then, on April 18, 2025, www.covid.gov and www.covidtests.gov were both redirected to a new White House website titled “Lab Leak: The True Origins of Covid-19.”

Particularly in the early days of the pandemic, the lab leak hypothesis was portrayed as a crazy conspiracy theory and was seen by many as being a rightwing dog whistle, along with any mention of Sweden’s more laissez-faire policies, the Danish Mask Study, and much more besides. This was part of the wider politicization of the virus, or rather, the official response to the virus. Broadly speaking, in the first weeks of the pandemic the American Left downplayed it, while the Right rang alarm bells, a trend that soon reversed entirely—ultimately the Left believed the pandemic was more serious than did the Right, and the Left supported the various mandates to a greater extent than the Right.

Should we err on the side of caution, especially in the beginning when we just don’t know, but do know the history of earlier pandemics?

Defining a conspiracy theory is tricky, and we shouldn’t conflate an elaborately constructed false narrative with a disputed fact. But when the line can be blurred, and when “conspiracy theorist” is itself sometimes used as a pejorative, the polarized debate over Covid can be tricky to navigate. “Covid vaccines didn't work” is false, but “Covid vaccines didn’t stop transmission, so mandating them, especially for those at little risk, was unnecessary” is true. Then again, if there’s any doubt at the time, why not err on the side of caution? Vaccination has proven to be among the most successful methods of modern medicine and much, much cheaper and less disruptive than shutdowns. “Masks didn’t work” is false, but “cloth masks generally had only a statistically insignificant health benefit” when deployed at scale is true. Then again, when in doubt, should we err on the side of caution, especially in the beginning when we just don’t know, but do know the history of earlier pandemics?

Why does any of this matter, especially as the pandemic fades into the rearview mirror? First, the truth is important, and we owe it to ourselves and to posterity to tell as full and accurate a story as possible, especially about such a major, impactful event. Secondly, we need to have a conversation about the failed response to Covid because not only were the various mandates on lockdowns, masks, vaccines and school closures much less effective than claimed, but also, many of those who questioned governmental and institutional narratives were demonized.

Authorities bet the farm on measures that were both divisive—mandates are almost always going to fall into this category—and ineffective.

On social media, dissenting voices were deplatformed or shadow-banned (a user’s content is made less visible or even hidden from others without the user being explicitly banned, or notified, or even aware that it has happened). So we never had an open and honest debate about possible alternative strategies, such as the Great Barrington Declaration authored by the Stanford physician-scientist and current NIH director Jay Bhattacharya. The authorities bet the farm on measures that were both divisive—mandates are almost always going to fall into this category—and ineffective. Dying on the hill of dragging traumatized 2-year old children off airplanes because they couldn’t keep a mask on was bizarre and even perverse, as was closing playgrounds, hiking trails, and beaches, and even the risibly ridiculous arresting of a lone paddleboarder off the coast of Malibu. Across the board, civil liberties were set back for years, while the consequences of school closures—both in terms of education and social development—have yet to be properly assessed (although preliminary studies indicate that students may be at least one year behind where they should be). And what about the level of preparedness of hospitals and medical equipment manufacturers? We need to talk about all this.

The next pandemic may have an attack rate and a case fatality ratio that would make Covid look like, well, the flu.

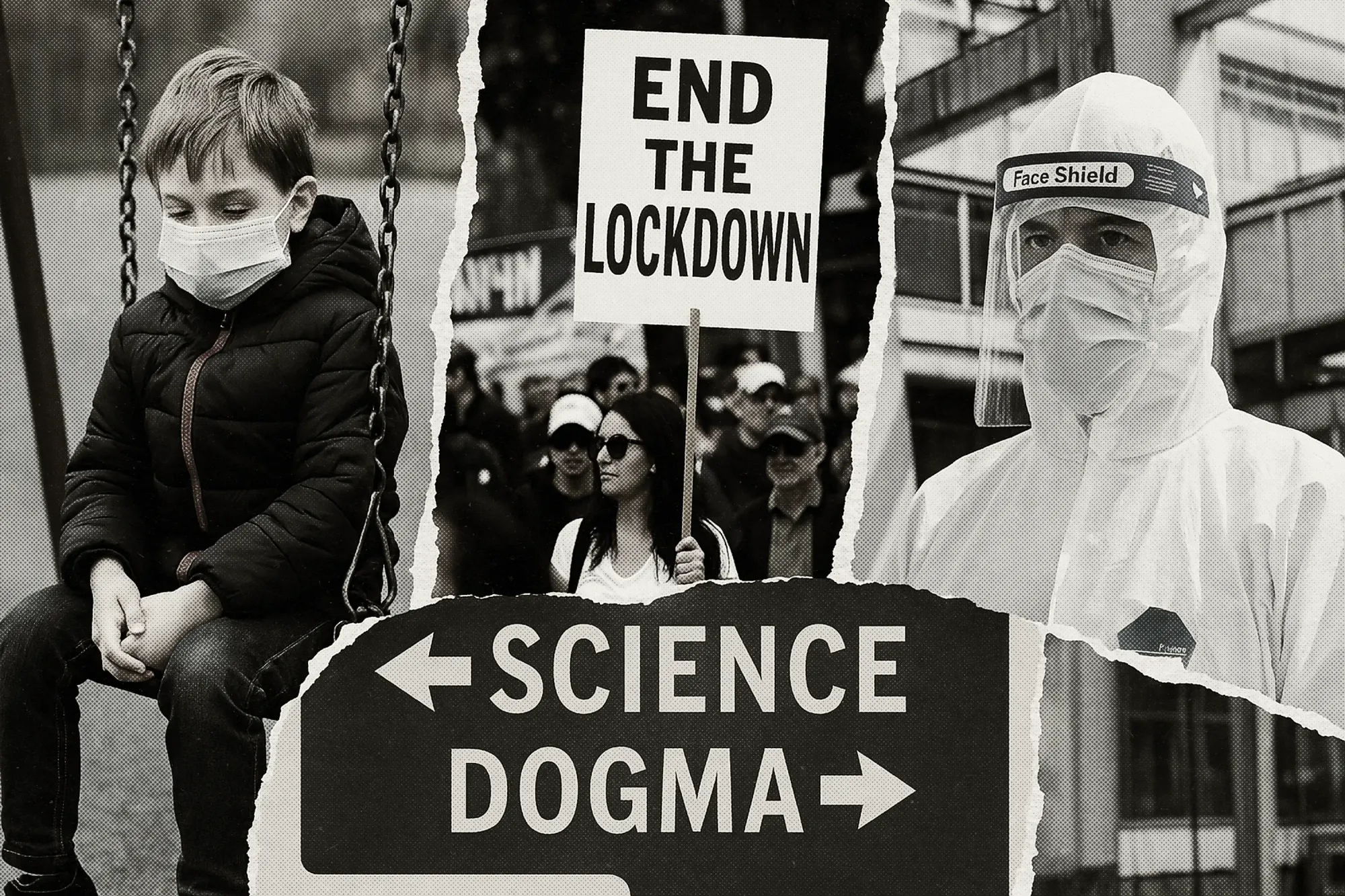

But most of all, this matters because of the next pandemic. It may be bird flu, the Nipah virus or mpox. Alternatively, it’ll be a Disease X that comes suddenly and unexpectedly from left field. But it’s inevitable, and the next pandemic may have an attack rate and a case fatality ratio that would make Covid look like, well, the flu. Such a pandemic would need a “we’re all in this together” response, just when half the country would regard such a soundbite as an Orwellian reminder of what many refer to as “Covid tyranny.” Trust in the public health system, and many other institutions, is at an all-time low. We need to depoliticize healthcare and ensure that never again do people misappropriate science by appealing to it but not following it (“masks and lockdowns, except for mass BLM protests”). We need a data-led approach and not a dogma-led one.

Having a full, robust and open national conversation about Covid—with accountability and apologies where necessary—is vital. That’s because identifying the mistakes and learning the lessons of the failed response to the last pandemic is essential in preparing to combat the next one.

Nick Pope’s new documentary film on which this essay is based is Apocalypse Covid. Watch the trailer here and the full film here.