CRISPR-Cas9 and the Ethics of Scientific Inaction

The Burmese python is among the most destructive invasive species in North America. Introduced into South Florida through the exotic pet trade, it has spread rapidly through the Everglades, fundamentally altering one of the most biologically unique ecosystems on the continent. Long-term monitoring studies document dramatic declines—often exceeding 90 percent—in medium-sized mammal populations such as raccoons, opossums, foxes, and bobcats. These losses have cascaded throughout the food web, reshaping predator-prey dynamics and ecosystem function.

After decades of effort, scientists and wildlife managers have been forced to confront an uncomfortable reality: traditional control strategies do not work at scale. Hunting programs, bounties, tracking dogs, radio-tagged “Judas snakes,” and public outreach campaigns have all failed to meaningfully reduce python populations across the Everglades’ vast and inaccessible terrain.

This persistent failure raises a question that should lie at the heart of scientific skepticism but is rarely posed directly: Why are scientists so reluctant even to explore CRISPR-based genetic tools to suppress invasive species when the ecological damage of inaction is already severe, ongoing, and irreversible?

To be clear, genetic population control has not remained confined to laboratory models. In Florida, genetically engineered mosquitoes have already been released in open environments to combat mosquito-borne disease—most notably dengue fever—while also reducing the risk of transmission of Zika and chikungunya viruses. These programs, developed by the biotechnology firm Oxitec, involved releasing male Aedes aegypti mosquitoes engineered so that their offspring fail to survive to adulthood. The goal was straightforward: suppress mosquito populations without pesticides and reduce disease risk to humans.

These releases were approved by federal and state regulators, implemented in the Florida Keys, and subjected to extensive monitoring. The results were not merely symbolic. Field trials conducted by Oxitec demonstrated local reductions of Aedes aegypti populations on the order of 70–90 percent, levels widely regarded as sufficient to substantially reduce the risk of mosquito-borne disease transmission. Notably, Aedes aegypti is itself a non-native, invasive species in Florida, introduced through human activity and now deeply embedded in urban and suburban environments. While directly attributing changes in dengue, Zika, or chikungunya incidence to a single intervention is methodologically complex, the biological rationale is straightforward: fewer competent vectors mean fewer opportunities for disease spread. By any reasonable standard, the program achieved its primary objective—large-scale, targeted suppression of an invasive species without chemical insecticides.

The ethical reasoning behind these deployments was equally clear. Faced with ongoing public-health risks, scientists and policymakers concluded that genetic population suppression was preferable to widespread pesticide use, which carries well-documented ecological and human-health costs. Precision, reversibility, and reduced collateral damage were treated not as liabilities, but as virtues.

What is striking … is not that such tools exist or that they work, but how narrowly their application has been circumscribed.

That judgment did not emerge in a vacuum. For more than three decades, genetically modified organisms have been deployed across global agriculture at enormous scale. Genetically engineered crops have reduced pesticide use, increased yields, improved resistance to pests and disease, and in some cases enhanced nutritional content. These organisms have been consumed by billions of people and introduced into ecosystems worldwide, all under regulatory regimes far less restrictive than those now proposed for CRISPR-based conservation tools. Despite early public alarm and immense leftist protests, the accumulated scientific evidence has shown GMO crops to be no more dangerous to human health or the environment than their conventional counterparts. In practice, genetic modification has become a routine—if still politically contested—part of modern environmental management.

What is striking, then, is not that such tools exist or that they work, but how narrowly their application has been circumscribed. Genetic population control has been judged acceptable when the target is an insect vector threatening human health, yet remains largely off-limits when the target is a vertebrate invasive species driving ecological collapse. The technology did not stall at the edge of feasibility or safety; it stalled at the edge of moral comfort. Human-centered risk is treated as actionable. Ecological destruction is treated as tolerable.

CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) is often portrayed as a radical, almost science-fictional technology—a sudden and unprecedented leap in human power over nature. Popular narratives frequently frame it as a tool that allows scientists to “rewrite life” at will, blurring the line between biology and engineering in ways that feel unsettling or unnatural. In reality, CRISPR did not emerge from speculative ambition, but from basic microbiological research into how bacteria survive viral infections. CRISPR is part of a naturally evolved bacterial immune system, one that has existed for billions of years and functions by recognizing and disabling invading genetic material.

This pattern of radical portrayal followed by gradual normalization is hardly unique to CRISPR. Earlier generations of genetic technologies were greeted with similar alarm. Recombinant DNA research in the 1970s provoked fears of runaway organisms and ecological catastrophe. Genetically modified crops were widely depicted as “unnatural,” dangerous, or morally suspect, despite being extensions of techniques humans had used for millennia to shape plant genomes through selective breeding. In each case, initial ethical anxiety was driven less by empirical evidence than by the perception that humans were crossing a symbolic boundary. Over time, as mechanisms became better understood and real-world outcomes failed to match apocalyptic predictions, these technologies were absorbed into routine scientific and agricultural practice. CRISPR now occupies the same cultural position once held by earlier genetic tools—exceptional not because of demonstrated harm, but because it makes human agency over biology unusually explicit.

What is CRISPR and how could it eliminate an invasive species?

When a bacterium survives a viral attack, it stores short fragments of the virus’s DNA in its own genome. These fragments serve as genetic “mugshots.” If the virus returns, the bacterium uses these sequences to guide specialized enzymes to recognize and cut the invader’s DNA, neutralizing the threat.

The most important of these enzymes is Cas9, a molecular tool capable of cutting DNA at a precisely specified location. In 2012, researchers including Jennifer Doudna demonstrated that this system could be repurposed as a programmable gene-editing technology. By supplying Cas9 with a custom guide RNA, scientists could target and cut virtually any DNA sequence with remarkable accuracy. In 2020, Doudna along with Emmanuelle Charpentier won the Noble Prize in chemistry for their discovery of the “CRISPR-Cas9 genetic scissors.”

This represented a qualitative leap beyond earlier genetic engineering techniques, which were slow, expensive, and often imprecise. CRISPR allows genes to be deleted, modified, or silenced with far greater control than any previous method.

This increase in precision has already translated into medical advances that, only a decade ago, would have been regarded as implausible or even miraculous. In several cases, CRISPR has moved beyond theory and into real-world clinical success, reshaping how genetic disease is treated.

Genetic approaches, by contrast, allow for ongoing monitoring, adjustment, and—if necessary—active reversal. The risk is not zero, but it is structured, visible, and governable in ways conservation biology has rarely had before.

One of the most striking examples involves inherited blood disorders such as sickle-cell disease and beta-thalassemia. Rather than attempting to correct the defective gene directly, researchers used CRISPR to reactivate fetal hemoglobin—a form of hemoglobin normally silenced after birth. In patients treated with this approach, debilitating symptoms have been dramatically reduced or eliminated, freeing individuals who once required frequent transfusions from lifelong medical dependence. These outcomes represent not incremental improvement, but functional cures.

CRISPR has also enabled remarkable progress in certain forms of blindness caused by single-gene mutations. In these cases, gene editing has been used directly in living patients to correct the underlying defect in retinal cells. For the first time, clinicians have been able to intervene at the level of genetic causation rather than managing symptoms after irreversible damage has occurred. Patients who were steadily losing vision have shown stabilization—and in some cases partial restoration of sight.

In cancer medicine, CRISPR has transformed immunotherapy by allowing scientists to engineer immune cells with unprecedented specificity. T cells can now be edited to better recognize tumors, resist immune exhaustion, or avoid attacking healthy tissue. These advances have expanded the reach of cell-based therapies and improved their safety profile, turning once-lethal cancers into manageable or even curable conditions for some patients.

What unites these examples is not technological novelty, but ethical clarity. In each case, CRISPR has been embraced because it replaces blunt, toxic, or ineffective treatments with targeted, biologically precise interventions. The risks are acknowledged, studied, and regulated—but they are not treated as disqualifying. When the benefits are concrete and human suffering is visible, society has proven willing to accept the responsible use of powerful genetic tools.

How does this translate into invasive-species control?

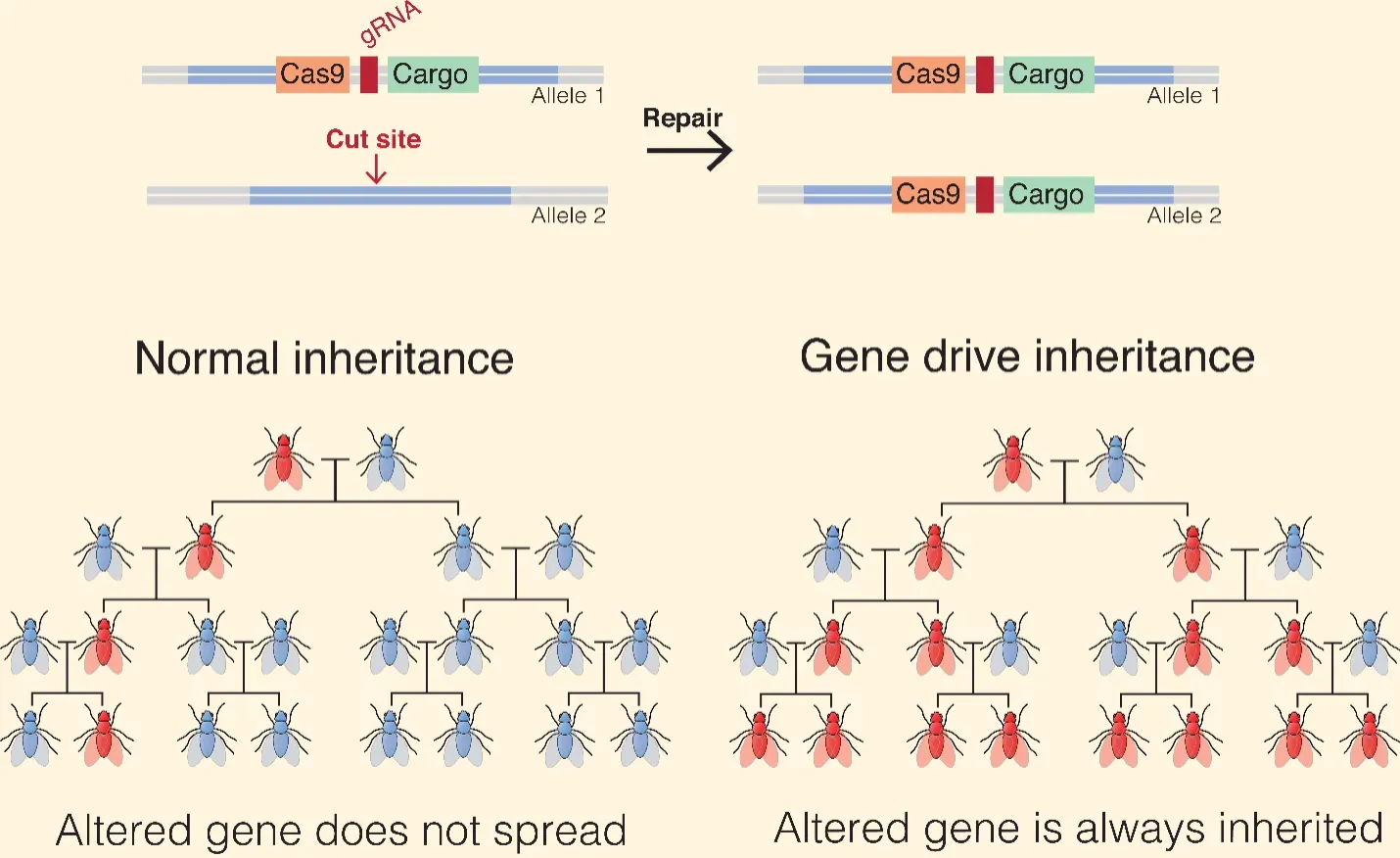

The most discussed application is the gene drive. Under normal sexual reproduction, each parent has roughly a 50 percent chance of passing on a given gene. A gene drive biases this process. By linking a genetic change to the CRISPR machinery itself, the altered gene is inherited by nearly all offspring, allowing it to spread rapidly through a population.

Crucially, eliminating an invasive species does not require mass killing or ecological vandalism. The most conservative proposals focus on population suppression rather than extinction. CRISPR can be used to disrupt fertility genes, bias sex ratios (for example, producing mostly males), or induce sterility without affecting survival. Over successive generations, reproduction fails and population size declines.

Equally important, these interventions can be designed to be species-specific, targeting DNA sequences unique to the invasive organism. Unlike chemical controls, they do not spread indiscriminately through food webs. Unlike physical removal, they scale naturally with population size.

A common concern is that a gene drive designed to suppress Burmese pythons in Florida, for example, could somehow spread beyond its intended range. In a worst-case scenario, modified individuals might be transported—most likely by humans—back to the species’ native range in tropical and subtropical regions of the Old World. If a population-suppression drive were to establish itself there, it could threaten native python populations rather than invasive ones. This possibility is real enough to deserve serious consideration, but it is also far less catastrophic—and far more controllable—than it is often portrayed.

First, such spread would be biologically and geographically unlikely. The Everglades are thousands of miles from the python’s native range, with no natural migration pathway connecting the two. Any transcontinental movement would almost certainly require deliberate or accidental human transport, the very mechanism responsible for the original invasion. Second, gene drives can be designed to be regionally constrained, for example by targeting genetic variants common in the invasive population but rare or absent in native populations, or by incorporating threshold-dependent systems that fail to propagate below certain population densities.

CRISPR does not act like a genetic bomb. It alters inheritance. That distinction matters.

Most importantly, CRISPR-based interventions are not a single, irreversible act. If an unintended spread were detected, there are multiple ways to halt or reverse progression. Researchers have already demonstrated the feasibility of reversal drives that overwrite earlier genetic changes, restoring normal inheritance patterns. In addition, releasing sufficient numbers of wild-type individuals can dilute or extinguish a suppression drive, while kill-switches and self-limiting designs can cause the system to collapse after a fixed number of generations.

In short, the relevant comparison is not between CRISPR and perfection, but between CRISPR and the tools currently in use. Chemical poisons, physical eradication, and habitat destruction offer no comparable capacity for recall or correction once deployed. Genetic approaches, by contrast, allow for ongoing monitoring, adjustment, and—if necessary—active reversal. The risk is not zero, but it is structured, visible, and governable in ways conservation biology has rarely had before.

CRISPR does not act like a genetic bomb. It alters inheritance. That distinction matters.

Unfounded Fears

Despite this precision, CRISPR is widely treated as uniquely dangerous. This perception collapses under comparison.

Humans already intervene in ecosystems aggressively and often imprecisely. We drain wetlands, reroute rivers, apply pesticides, release biological control agents, and physically remove animals by the thousands. These interventions frequently produce collateral damage—not because intervention itself is misguided, but because it is undertaken with insufficient ecological understanding. Classic examples illustrate the danger of blunt solutions.

In the 1930s, cane toads were introduced into Australia in an attempt to control beetles harming sugarcane crops. The toads failed to control the pests but thrived spectacularly themselves, spreading rapidly across the continent and poisoning native predators unadapted to their toxins. Similarly, mongooses were introduced to Hawaii to control rats in sugar plantations, only to prey instead on native birds and reptiles that had evolved without mammalian predators. In both cases, well-intentioned biological interventions backfired—not because humans acted, but because they acted crudely, deploying organisms broadly without precision, containment, or the ability to reverse course. These disasters argue not against intervention itself, but against uninformed and irreversible intervention.

CRISPR, by contrast, is the most targeted biological tool humans have ever developed. If risk is defined as the probability of unintended harm multiplied by the magnitude of that harm, it is far from obvious that CRISPR represents a new category of danger. In many contexts, it may represent a reduction in risk relative to existing practices.

Yet CRISPR is held to an ethical standard no other ecological tool has ever faced: near-zero tolerance for uncertainty.

A Brief History of Invasive-Species Eradication

The ethical hesitation surrounding CRISPR appears far less principled when placed alongside the long history of invasive-species eradication already embraced by conservation biology. For decades, conservationists have pursued aggressive—and often lethal—campaigns to remove non-native predators, particularly on islands where endemic species evolved without defenses against mammalian hunters.

As vividly documented in William Stolzenburg’s Rat Island, invasive rats, cats, and other predators introduced inadvertently by humans have devastated island ecosystems worldwide. Flightless birds such as New Zealand’s kakapo, along with countless seabirds and reptiles, have been driven to the brink of extinction by predators they were evolutionarily unprepared to confront. Faced with these losses, conservationists have largely converged on a difficult conclusion: eradication, however uncomfortable, is preferable to permanent biodiversity collapse.

The primary tool for rat eradication has often been chemical poisoning, most notably anticoagulants such as brodifacoum. These compounds cause internal bleeding over the course of days, a process widely acknowledged to be painful. Their use has also produced unintended consequences, including secondary poisoning of birds of prey that consume contaminated rodents. Yet despite these ethical and ecological costs, eradication campaigns have continued—because the alternative is the irreversible loss of native species.

CRISPR deserves no exemption from scrutiny—but neither does it warrant a moral quarantine that more destructive methods escape entirely.

This history matters because it reveals a striking inconsistency. Conservation science already accepts deliberate, population-level elimination of invasive species using methods that are blunt, ecologically disruptive, and morally fraught. These approaches are justified, explicitly, as tragic but necessary tradeoffs.

Against this backdrop, objections to CRISPR take on a different character. Genetic approaches aimed at reproductive suppression rather than mass killing could, in principle, reduce or eliminate invasive populations without poisoning, trapping, or collateral damage to non-target species. They offer the possibility—still theoretical, but biologically grounded—of achieving the same conservation goals with less suffering and greater precision.

To be clear, gene drives introduce their own uncertainties. But uncertainty has never been grounds for abstention in conservation biology. Instead, uncertainty has been managed through testing, containment, and ongoing revision. CRISPR deserves no exemption from scrutiny—but neither does it warrant a moral quarantine that more destructive methods escape entirely.

Triage

The uncomfortable truth is that conservation already involves deciding which species live and which disappear. The real ethical question is not whether humans should exercise that power—we already do—but whether we are willing to consider tools that might allow us to exercise it more carefully, more precisely, and with fewer unintended victims.

Before CRISPR is dismissed as reckless or premature, it is worth asking a simpler question: what has already been tried—and at what cost?

Florida and federal agencies, along with conservation organizations, have spent tens of millions of dollars attempting to control Burmese python populations. No attempted action has achieved population-level suppression.

Among the most striking examples is the development of robotic prey decoys, including AI-assisted robotic rabbits designed to lure pythons into traps. These devices mimic the movement, heat signatures, and behavioral cues of live prey. They represent an impressive feat of engineering—complex, expensive, and technologically adventurous.

They are also revealing.

Robotic prey baits are essentially a high-tech extension of trapping. They operate on one animal at a time, across thousands of square miles of dense, inaccessible wetlands. Even when successful, they remove pythons incrementally, with no capacity to scale proportionally to population size. Meanwhile, reproduction continues unchecked.

When scientists decline even to explore genetic interventions, they are not abstaining from responsibility—they are exercising it selectively.

This matters because it exposes a profound inconsistency in how risk is evaluated. The same institutions that recoil at the hypothetical risks of CRISPR have already embraced experimental technologies deployed directly into the wild, large-scale ecological manipulation, and interventions with no realistic path to success

Robotic prey baits are not inherently unethical. But they are far cruder, less targeted, and less scalable than genetic approaches—yet they trigger none of the moral alarm bells that CRISPR does.

Society, it seems, is already willing to experiment aggressively in the Everglades.

The Burmese python did not arrive in Florida by natural dispersal. Its presence is the result of human action. Continuing to allow its ecological destruction is also a human choice. When scientists decline even to explore genetic interventions, they are not abstaining from responsibility—they are exercising it selectively.

But doing nothing is not neutral.