Dice, Mr. Smith, and Monty: The Case for Clarity in Probability Puzzles

Imagine you are at a puzzle night with friends. Someone poses this question: “You roll two dice. At least one shows a six. What’s the probability both show a six?”

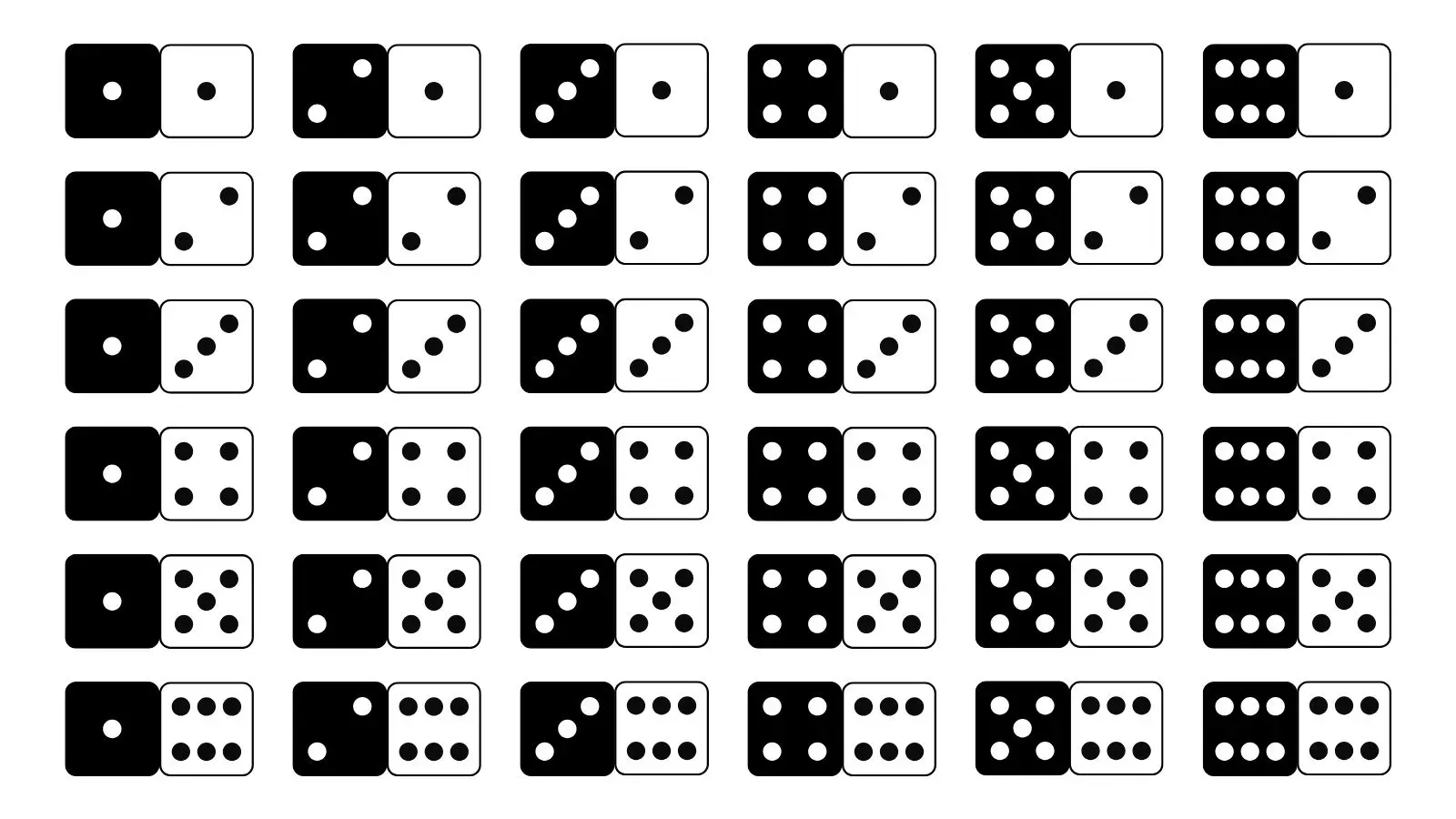

The table splits: Half the people argue that the dice are independent, so the answer must be one in six. The other half insists it’s one in 11. They may refer to the image below: There 11 equally-likely ways that a roll of two dice can show at least one six (bottom row and rightmost column), and in one of these rolls, they are both sixes.

So who’s right? Both—and neither. The correct answer is: “We can’t answer this without more information.” Depending on how you came to the information that there was at least one six, the answer can be one in six or one in 11.

Many so-called probability “paradoxes” arise from vague framing. In practice, data are generated by processes. Those processes define the pool of possibilities—and thus the probabilities. When the information-generating process isn’t specified, reasonable people can come up with different answers because they’re answering different questions.

Double-Six Puzzle

Let’s return to the opening question. To reveal the ambiguity, I’ll frame it in two ways:

Puzzle 1: You roll two dice. One of them falls under the table and you can’t see it. The other one lands on top of the table, and it’s a six. What is the probability that both dice landed on a six?

Puzzle 2: You are rolling two dice blindfolded. A machine is programmed to ding if and only if at least one of them lands on a six. You keep rolling until the machine dings. What is the probability that both dice landed on a six?

Solutions

Puzzle 1: The probability that both dice landed on a six is one in six. In this scenario, you’ve learned a fact about a particular die: the one you can see is a six. The first die doesn’t affect the second, so the six possible outcomes of the second die are equally likely.

Puzzle 2: The probability that both dice landed on a six is one in 11. In this scenario, you don’t have information about a particular die; the ding of the machine only tells you a property of the pair. This roll passed a filter that admits only outcomes with at least one six. Among the 36 ordered outcomes of two dice, 11 contain at least one six. Only one of those 11 outcomes is the double six.

Both of these puzzles answer the question “You rolled two dice. At least one shows a six. What’s the chance both show a six?” However, since they have different information-generating processes, they have different solutions.

Boy or Girl Paradox

In Martin Gardner’s famous “Boy or Girl Paradox,” sometimes called the “Two-Child Problem,” he poses this question: “Mr. Smith has two children. At least one is a boy. What is the probability that both children are boys?”

If this puzzle sounds familiar, that is because it is like the dice puzzle. Even if we adopt the assumption that births are like coin flips (i.e., independent, equally likely boy or girl, no multiple births), the puzzle is unanswerable. Gardner initially proclaimed the answer was “one in three,” but later admitted that the puzzle was ambiguous. The problem is that it does not tell us how we learned that at least one child is a boy.

Imagine you randomly meet a man named Mr. Smith at the park. He’s with one child, and that child is a boy. He mentions he has another child at home. What is the probability the child at home is a boy?

Seeing the boy in the park tells us nothing about the child at home. The possibilities are simply: “boy at the park, girl at home” or “boy at the park, boy at home.” Those two possibilities are equally likely, so the answer is one in two. The “child at the park” is like the die you can see and the “child at home” is like the die under the table.

When the information-generating process isn’t specified, reasonable people can come up with different answers because they’re answering different questions.

Now imagine you have a list of all men named Mr. Smith in your city who have two children and at least one boy. You pick a man at random from that list. What are the chances both his children are boys? The four ordered possibilities in all two-child families are GG, GB, BG, and BB. However, your list excludes GG. That leaves GB, BG, BB–three equally likely families, only one of which is BB. So the probability is one in three. This “filtered list” setup is like the machine-ding scenario: your knowledge is based on a property of the pair, not a particular child.

In both stories, it is true that Mr. Smith has two children and at least one is a boy. The answers differ because we came to know that fact in different ways.

The Monty Hall Problem

The best-known version of the Monty Hall problem was posed by Craig F. Whitaker to Marilyn vos Savant in a 1990 issue of Parade magazine, one of the most widely read publications in the country at the time:

Suppose you’re on a game show, and you’re given the choice of three doors: behind one door is a car; behind the others, goats. You pick a door, say No. 1, and the host, who knows what’s behind the doors, opens another door, say No. 3, which has a goat. He then says to you, “Do you want to pick door No. 2?” Is it to your advantage to switch your choice?

Marilyn answered, “Yes; you should switch. The first door has a 1/3 chance of winning, but the second door has a 2/3 chance.”

The magazine received over 10,000 letters, including many from highly educated readers, insisting that this answer was wrong. Don Edwards, from Sunriver, Oregon, suggested: “Maybe women look at math problems differently from men.” A Georgia State University professor, one W. Robert Smith, PhD, advised: “I am sure you will receive many letters on this topic from high school and college students. Perhaps you should keep a few addresses for help with future columns.” Another PhD correspondent, a University of Florida professor named Scott Smith, exclaimed:

You blew it, and you blew it big! Since you seem to have difficulty grasping the basic principle at work here, I’ll explain. After the host reveals a goat, you now have a one-in-two chance of being correct. Whether you change your selection or not, the odds are the same. There is enough mathematical illiteracy in this country, and we don’t need the world’s highest IQ propagating more. Shame!

Today, it’s widely accepted that Marilyn was right. People have even built computer simulations that reproduce the result. The story is often cited as a reminder that probability can be counterintuitive, and as a lesson that confidence and credentials don’t make us immune to mistakes. Those are valuable lessons—but I think much of the pushback came from a simpler reason: the problem phrasing was too vague.

For Marilyn’s solution to be correct, the game must guarantee from the start that the host will open a door showing a goat. This needs to be explicitly stated as a rule of the game. Many readers assume that the host knowing what’s behind the doors implies that he is guaranteed to open a goat door. But even if the host knows, that alone does not tell us what he is obliged to do. Marilyn’s answer relies on the following assumptions:

1. The host always opens a door after your initial choice.

2. He never opens the door with the car.

Simulations built to show why Marilyn’s answer is correct have these assumptions built into their programming. But if those conditions aren’t guaranteed, the probabilities change.

If we make the above two assumptions, then Marilyn’s advice is correct–you should switch. This can be explained simply:

• If your initial choice was a goat door, switching will certainly give you the car. Since there is a 2 in 3 chance your initial choice was a goat, there is a 2 in 3 chance you will win if you switch.

• If your initial choice was the car door, you will certainly lose if you switch. Since there is only a 1 in 3 chance your initial choice was the car, there is a 1 in 3 chance you will lose if you switch.

This reasoning treats the host’s action as guaranteed and therefore uninformative about your original choice. If the host’s behavior is left unspecified, the fact that he opened a goat door can give you different information. Here are two variations of the puzzle that help to demonstrate that.

Optional Opening Variation

On a game show, there are three doors. Behind one is a car; behind the others, goats. After contestants choose a door, the host sometimes opens another door to show a goat (he never reveals the car). If he does open a door, he then offers you the chance to switch to the other closed door. It’s your turn: You pick a door, and the host opens a goat door. He offers a choice to switch to the other unopened door. What should you do?

You can’t answer this until you know the host’s policy—how often he opens a door given that a contestant’s initial pick is the car versus a goat. If the host is much more likely to open a door for contestants who initially picked the car, then seeing him open a door increases the likelihood that the car is behind your chosen door. Different policies lead to different conditional probabilities, so the question is unanswerable without more information.

Random Door Variation of the Monty Hall Problem

On a game show, there are three closed doors. Behind one is a car; behind the others, goats. After contestants pick a door, the host randomly opens another door. If he reveals a car, it’s game over. It’s your turn to play! You choose a door. The host randomly opens another door. It’s a goat! He offers a choice to switch to the other unopened door. What should you do?

It can help to think of this game being played many times. One third of players initially pick the car. For them, the host will always reveal a goat. Two thirds of players initially pick a goat. For them, the host reveals a goat half the time and reveals the car the other half. If we consider all games, we can split the players into three equal groups:

- Picked the car and saw a goat

- Picked a goat and saw a goat

- Picked a goat and saw the car

All of these scenarios are equally likely, so a third of the players will be in each group. Since the question tells you that, in your game, the host opens a door that has a goat, you know that you are in either group 1 or 2. Since it is equally likely that you are in either one, switching or staying makes no difference.

Once you state the host’s policy clearly, many people who previously found the problem baffling finally see where the answer comes from.

The crucial difference is that here the host could have shown the car but didn’t. In this variation, the host is more likely to open a goat door if your initial pick was the car door. In other words, the host opening a goat door gives you information about your initially chosen door: it increases the probability that it has a car from ⅓ to ½.

A Clearer Phrasing

Here is a clear way to pose the problem such that Marilyn’s answer is correct:

You are about to go on a game show. The game is always played in the same way: The player is shown three closed doors. Behind two of them are goats; behind one is a car. The player wins if they pick the door with the car. After the player picks a door, the host opens another door, and it's always one with a goat behind it. Then the host offers the player the chance to switch to the other closed door. He does this in every game. What should you do to maximize your chances of winning?

You may have noticed that I also specified that you win if you pick the car door (not that you win what’s behind the door). This is because sometimes people say they prefer a goat over a car.

Clarity is crucial, whether you’re posing a puzzle or talking with someone who sees things differently than you do.

The problem with the Monty Hall problem is that the standard wording is often too vague. Marilyn’s answer is correct only under a particular set of rules about what the host will do, but those rules are frequently left out. Once you state the host’s policy clearly, many people who previously found the problem baffling finally see where the answer comes from.

For readers familiar with Bayes’s theorem, I leave you with a challenge:

You’re playing a game with the same setup as above, but now you’re told the host opens a door 75 percent of the time when the contestant initially picks a goat, and 25 percent of the time when the contestant initially picks the car. In your game, the host opens a door to show a goat. Should you switch or stay?

The “Obvious” Interpretation

For many such probability puzzles, one might object, “But the most natural interpretation is obviously X.” Natural to whom? When a puzzle leaves out the information-generating process, people may assume different backstories and end up answering different problems. What seems obvious to you may not be to someone else.

This lesson applies beyond puzzles. In many disagreements, people talk past each other because they understand the same term in different ways or are working from different assumptions. When you make those terms and assumptions explicit, you may find you disagree on less than you thought. Even if you don’t, that precision lays the groundwork for a more productive discussion. Clarity is crucial, whether you’re posing a puzzle or talking with someone who sees things differently than you do.