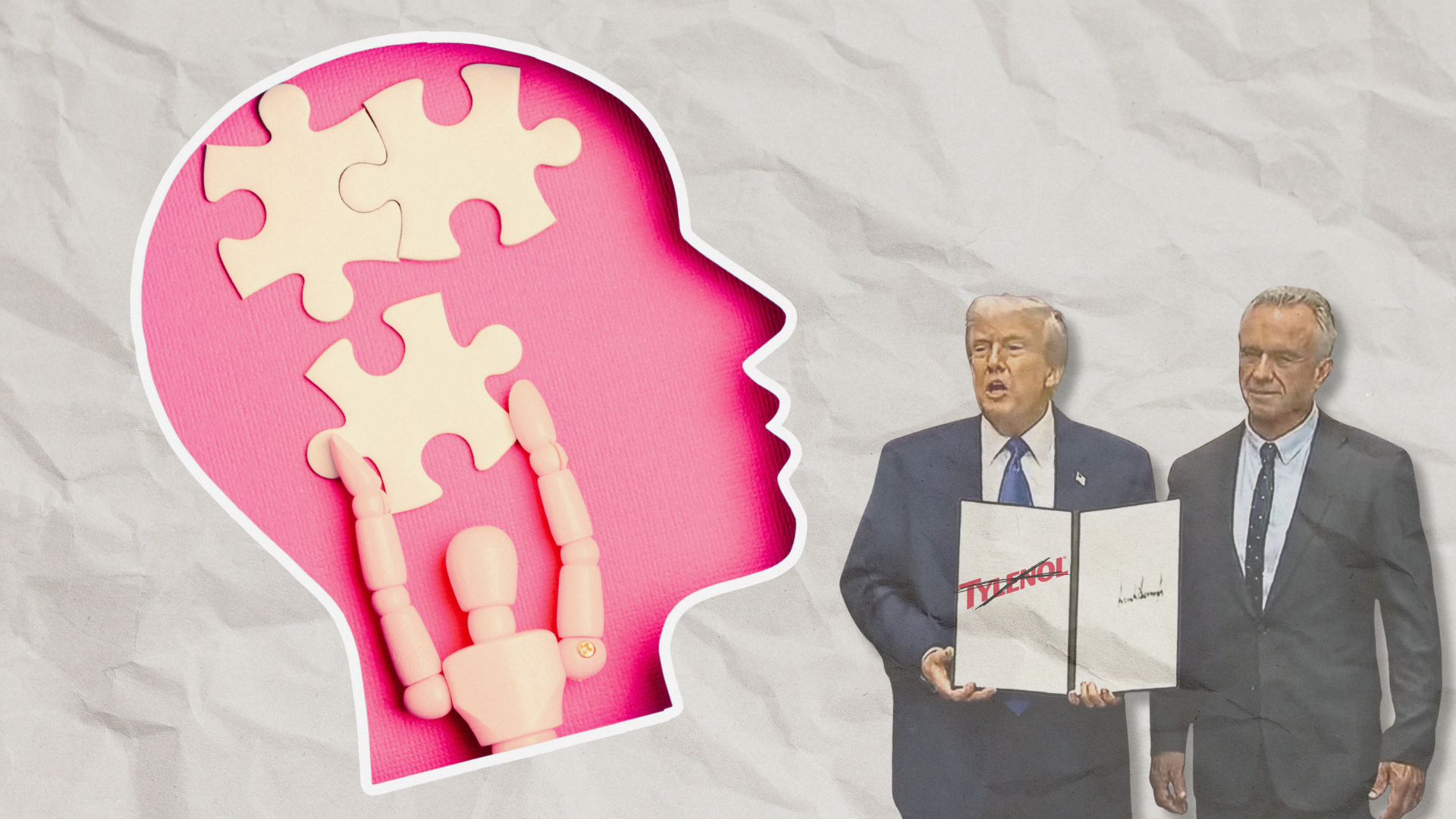

Does Tylenol Cause Autism? Here’s What The Evidence Says

The drug cabinet of a pregnant woman today is already a minefield of anxiety. Now a potent new variable has been introduced: political theater. When the President of the United States and the Secretary of Health and Human Services suggested on September 22, 2025 that acetaminophen—known globally as paracetamol and in the U.S. by the brand name Tylenol—causes autism, the public health impact was immediate, sweeping, and, crucially, dangerous.

Acetaminophen is known globally as paracetamol and in the U.S. by the brand name Tylenol.

This article, written from a perspective of scientific skepticism and practical medicine (I’m a full-time practicing physician), will look at the claims linking prenatal acetaminophen use to neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs), specifically ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorder) and ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder). We will look at the observational evidence that initially raised alarms, the methodological rigor that subsequently debunked causality, and the immediate, real-world risks created by scaremongering that rests on shaky research that has failed to convince the scientific community.

Correlation is Not Causation and the Problem of the Autism “Epidemic”

The debate over acetaminophen (APAP) and autism occurs against a backdrop of dramatically increased NDD diagnoses. Over the past two decades, autism diagnoses have risen by nearly 300 percent. This rise has fueled the persistent, yet misleading, phrase “epidemic of autism.”

Autism diagnoses have risen by nearly 300 percent. Epidemiologists argue that this surge is caused by a profound change in definition and therefore detection.

However, epidemiologists consistently argue that this surge is not caused by a new environmental or pharmaceutical change affecting incidence, but rather a profound change in definition and therefore detection. Dr. Christine Ladd-Acosta, Vice Director of the Wendy Klag Center for Autism and Developmental Disabilities, explains that the increase is primarily due to two factors: (1) the broadened definition of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and (2) widely successful public health programs that increased screening and community awareness. The highest rates of increase are seen in individuals with “more subtle phenotypes” who may previously have gone undiagnosed, suggesting enhanced identification, not increased occurrence.

While the descriptor “epidemic” implies a sudden, rapid increase, the gradual 10–20 percent rise every two years observed in autism rates does not fit the definition. This distinction is critical, as it reframes the search for environmental causes from a desperate hunt for the single culprit behind a sudden catastrophe, to a more careful epidemiological effort to understand subtle risk factors interacting with strong genetic predispositions.

The Evidence for Association—and Why It Doesn't Prove Causation

Acetaminophen has long been recommended as the safest pain medicine for use during pregnancy. Yet, starting in the 2010s, observational studies—asking parents of children with a diagnosis of NDD what medication they had used during the pregnancy—began reporting a measurable association between prenatal exposure and NDDs, primarily ADHD and, to a lesser extent, ASD.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have identified clear statistical correlations. For example, an umbrella review of five systematic reviews reported significant associations between maternal prenatal acetaminophen use and ADHD outcomes in children, with Risk Ratios (RR) ranging from 1.08 to 1.34. One meta-analysis found acetaminophen exposure yielded an RR of 1.34 for ADHD outcomes and 1.19 for ASD outcomes.

(Risk ratio is a measure that compares the likelihood of a specific event occurring in one group versus another. It is calculated by dividing the risk of an event in an exposed group by the risk of the same event in a non-exposed or control group. A risk ratio of 1 means no difference in risk, a ratio greater than 1 indicates an increased risk, and a ratio less than 1 signifies a decreased, or protective, risk.)

Furthermore, some analyses suggested a dose-response relationship, indicating that the risk was magnified by prolonged use. Exposure lasting 28 consecutive days or longer was associated with an RR of 1.63 for ADHD outcomes. Associations were also linked more strongly to use in the third trimester, a period of rapid fetal brain development and differentiation.

The existence of a statistical association is insufficient for proving causality.

The skeptical mind should acknowledge that these associations might be pointing to a biologic possibility that could elevate a statistical correlation above chance. Acetaminophen is known to cross the placenta due to its lipid solubility and low molecular weight. Hypothesized mechanisms include its role as an endocrine disruptor and potential links to genital malformations. Researchers have suggested that acetaminophen use might indirectly affect the developing fetal brain by modulating the endocannabinoid system or altering dopamine metabolism and levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), pathways relevant to ADHD and ASD etiology. These potential connections have not been proven but have spurred some researchers to issue a “call for precautionary action” based on the accumulated evidence of association.

But we need to remind ourselves—over and over—that the existence of a statistical association, even one supported by theories of possible mechanistic causal factors—is insufficient for proving causality. This is where methodological rigor—the true measure of scientific skepticism—comes into play. The primary weakness of early observational studies is their susceptibility to confounding (in which other variables distort the observed relationship between an independent cause and a dependent effect variable in a study), for example “familial confounding,” or unobserved factors shared within a family that influence both the likelihood of drug use and a child’s risk of developing an NDD.

The most powerful counter-argument against the causal link comes from the nationwide Swedish cohort study, which analyzed 2,480,797 children born between 1995 and 2019. Initially, crude models without strict controls showed that “ever-use” of acetaminophen during pregnancy was associated with a marginally increased risk of autism (Hazard Ratio [HR], 1.05) and ADHD (HR, 1.07). This is the association cited by those advocating for caution. However, the researchers followed up with a careful sibling control analysis. This design compares outcomes between full siblings where one was exposed to acetaminophen prenatally and the other was not. Because siblings share similar genetics, socioeconomic background, and exposure to many familial environmental factors, this comparison effectively removes the influence of stable, unobserved confounding variables. The results were unequivocal:

- In the sibling control analysis, acetaminophen use during pregnancy was not associated with autism (HR, 0.98; risk difference [RD], 0.02 percent).

- The use was also not associated with ADHD (HR, 0.98) or intellectual disability.

The study’s authors concluded that the associations observed in less-robust models “may have been attributable to familial confounding.” Renee Gardner, one of the study’s authors, suggested that genetic tendencies that increase the risk of autism often overlap with genes influencing pain perception, meaning the genetic risk factor causes both pain (leading to paracetamol use) and autism, making the painkiller an innocent bystander.

Why were some pregnant women using Tylenol in the first place, some as long as four weeks in a row?

This leads us to look at the indication for use. Why were some pregnant women using Tylenol in the first place, some as long as four weeks in a row? Untreated maternal conditions like fever, chronic pain, or inflammation are known risk factors for adverse outcomes in offspring. If the mother is taking acetaminophen because she has a severe infection or chronic migraine, the drug may simply be a proxy for the underlying illness, which is the true confounding factor in the observed association.

One common, though often overlooked, familial confounder involves the complex relationship between pain sensitivity and neurodevelopment. As Gardner explained, maternal conditions like hypermobility (unusually flexible joints)—which can cause joint pain requiring painkillers—are also “more likely to have autistic children.” If researchers fail to account for this overlap, “painkillers can wrongly appear to be a risk factor.”

Skeptics should also look at the evidence countering this study. Critics, including Ann Bauer and Shanna Swan, argue that the Swedish study’s conclusion—that the association is entirely confounded—is premature due to methodological limitations. They point out, for example, that the reported acetaminophen usage rate in the Swedish cohort (7.5 percent) was “far lower than what is reported in studies around the world” (which typically report around 50 percent). This suggests high rates of exposure misclassification, which, if not dependent on the outcome, “would bias results toward the null, or ‘no effect’.” In other words, if many exposed mothers were misclassified as unexposed, the benefit of the sibling control design is dampened.

Furthermore, these critics caution that the sibling-control design, while excellent for controlling for confounders, might inadvertently control for mediators—variables that lie on the causal pathway between exposure and outcome. If acetaminophen triggers a biological change (e.g., endocrine disruption) that is genetically sensitive and leads to NDDs, the sibling control could eliminate this genuine causal mechanism, introducing a different form of bias. Given that experimental animal studies have identified biological mediators related to the endocannabinoid system and oxidative stress, Bauer and Swan urge “caution in interpreting the study’s conclusions regarding the causal relationship.”

Enter Politics

This critique highlights that while the Swedish study drastically undercut the causality argument, the scientific door remains slightly ajar, requiring continued prudence regarding heavy or chronic use. Unfortunately, the scientific nuances of familial confounding, misclassification bias, and mediators versus confounders were recently abruptly jettisoned from public discourse in favor of dramatic political statements.

The political rhetoric took the association several steps further than the cautious scientific findings would allow.

The claims linking acetaminophen to autism, notably pushed by President Donald Trump and Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., are based, in part, on research showing evidence of an association, such as the review co-authored by Harvard Public Health Dean Andrea A. Baccarelli. However, the political rhetoric took the association several steps further than the cautious scientific findings (above) would allow. President Trump flatly advised, “Don’t take Tylenol. Don’t take it. Fight like hell not to take it,” alleging it was associated with a “very increased” autism risk.

This message has been criticized for being “mistakenly and cruelly pitch[ing] women’s needs against the best interests of their baby.” Professor Sarah Hawkes noted that the rhetoric introduces “stigma and guilt” for parents of autistic children. The fear is magnified by the FDA's decision to initiate the process of including a warning about a “possible association” with autism risk on product safety labels, even while emphasizing that causality has not been established. Since the White House’s announcement, it has also been reported that hospitalized and outpatients who are male, and women who are not pregnant, have been refusing to take acetaminophen out of fear of the unknown. The key point here is that this advice—to avoid the drug at all costs—ignores the known, immediate risks of non-treatment:

- Risk of Untreated Illness: Fever in pregnancy is not benign. Untreated high fever is associated with miscarriage, congenital malformations (including cardiac defects and neural tube defects), preterm delivery, and intrauterine fetal demise.

- Risk of Substitution: Acetaminophen remains the safest over-the-counter analgesic during pregnancy. Discouraging its use risks pushing women toward alternatives such as ibuprofen (a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug or NSAID), which has documented, proven risks in pregnancy, including fetal kidney damage and premature closure of the ductus arteriosus (a temporary blood vessel that connects the aorta—the main artery of the body—to the pulmonary artery—the artery that carries blood to the lungs—in the fetus). As epidemiologist Prof. Laurie Tomlinson noted, “Paracetamol is far and away the safest painkiller in pregnancy so if women are more reluctant to take it they are going to be suffering unnecessarily.”

Summary of Risks and Recommendation

The highest-quality scientific evidence, specifically the robust methodology of sibling-control analysis, does not support a causal link between maternal acetaminophen use and the risk of ASD or ADHD. The observed initial statistical associations are best explained as familial confounding.

However, given the political and public health landscape, we can suggest a balanced approach, acknowledging the persistence of associations in some studies and the biological plausibility of harm from chronic, high exposure.

Summary of Risks at This Time

|

Risk Category |

Nature of Risk |

Evidence Status |

|

Exposure Risk (Acetaminophen) |

Theoretical, marginally increased absolute risk of NDDs (e.g., 0.09 percent for autism). |

High Confounding: Overwhelmingly attributable to familial and underlying health factors (e.g., indication for use). Weak evidence of a causal link. |

|

Avoidance Risk (Untreated Symptoms) |

Proven, severe risks from untreated fever (miscarriage, congenital malformations, fetal demise). |

Established: Strong evidence that the harms of untreated fever/pain outweigh the non-causal associations of the treatment. |

|

Substitution Risk (Alternative Drugs) |

Proven risks from using alternative analgesics (e.g., Ibuprofen). |

Established: Acetaminophen is the safest available first-line treatment. |

|

Societal Risk (Scaremongering) |

Increased maternal anxiety, guilt, and mistrust in medical science. |

Observable: Direct consequence of irresponsible public statements. |

Recommendation for Risk Management

Clinicians and pregnant women should remain rational and evidence-driven, resisting the “theater of scaremongering.” Acetaminophen remains the safest and most effective first-line treatment for pain and fever during pregnancy. The key management recommendation is judicious use:

- Use Only When Necessary: Health professionals should advise women to use acetaminophen only when medically required, such as for persistent pain or high fever.

- Minimal Dosage, Minimal Duration: Follow the guideline of using the “lowest effective dose for the shortest possible duration” under medical guidance. This is good advice for ALL medications.

- Prioritize Fever Treatment: High fever must be treated due to its documented risks to the fetus. Pregnant women should be reassured that treating fever with acetaminophen is safer than allowing the fever to persist.

In the complex nexus where politics, public health, and perinatal science meet, skepticism demands we follow the most rigorous evidence. That evidence confirms that while caution is warranted in all drug use during pregnancy, the proven risks of foregoing necessary treatment far outweigh the confounding-laden claims of a causal link between Tylenol and neurodevelopmental disorders.