It’s About Respect, Stupid

In 2020 Joe Biden became the first Democratic nominee in 36 years without a degree from the Ivy League. Obama, before him, filled no less than two-thirds of all cabinet positions with Ivy League graduates—over half of which were drawn from either Harvard or Yale.1 In Congress today, 95 percent of House members and 100 percent of senators are college educated.

According to a recent study published in Nature, 54 percent of “high achievers” across a broad range of fields—law, science, art, business, and politics—hold degrees from the 34 most elite universities in the country.2 The sociologist Lauren Rivera, studying top firms in finance, consulting, and law, found that recruiters are jonesing for applicants from a prestigious academic institution; typically targeting just three to five “core” universities in their hiring efforts—Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Stanford, and MIT—the usual suspects; then identifying five to fifteen additional second-tier options—such as Berkeley, Amherst, and Duke—from which they will more tentatively accept resumés.3 Everyone else—almost certainly never even gets a reply email. Why? Because, one lawyer explained the strategy to Rivera, “Number one people go to number one schools.”

“If destruction be our lot, we must ourselves be its author and finisher.” —Abraham Lincoln

Given this new American caste system, it’s no surprise that 63 percent of Americans think that “experts in this country don’t understand the lives of people like me,” or that 69 percent feel the “political and economic elite don’t care about hardworking people.”4 And, I suggest, they’re not wrong. A culture that sanctifies college as the gateway to full citizenship, over time corrodes the foundations of democratic life. It devalues work that doesn’t come with a degree, licenses contempt for those not formally educated, and locks the working class out of positions of power. The result isn’t just underrepresentation; it’s resentment. As the journalist David Goodhart writes, “We now have a single route into a single dominant cognitive class”; where “an enormous social vacuum cleaner has sucked up status from manual occupations, even skilled ones,” and appropriated it to white-collar jobs, even low-level ones, in “prosperous metropolitan centers and university towns”; and where broad civic contribution has been replaced with narrow intellectual consensus.5 The result is a backlash not against education, but against the assumption that only one kind of education counts.

“At a time when racism and sexism are out of favor,” writes Harvard philosopher Michael Sandel, “credentialism is the last acceptable prejudice.”6 In a cross-national study conducted in the United States, Britain, the Netherlands, and Belgium, a team of social psychologists led by Toon Kuppens found that the college-educated class had a greater bias against less educated people than they did other disfavored groups.7 In a list that included Muslims, poor people, obese people, disabled people, and the working class, “stupid people” were the most disliked. Moreover, the researchers found that elites are unembarrassed by the prejudice; that unlike homophobia or classism, it isn’t hidden, hedged, or softened—it’s worn openly, with an air of self-congratulation. As the Swedish political scientist Bo Rothstein observes, “The more than 150-year-old alliance between the industrial working class and what one might call the intellectual-cultural Left is over.”8

Today we are living through a strange time in American life in which the numbers have declared victory. By most standard economic measures—employment, wages, even household net worth—the working class is better off than it was a generation ago.9, 10, 11 The average elevator mechanic gets paid over $100,000 per year12; master plumbers can make more than double that.13 Even in Mississippi, our country’s poorest state, workers see higher average wages than in Germany, Britain, or Canada.14

Elites are unembarrassed by the prejudice; that unlike homophobia or classism, it isn’t hidden, hedged, or softened—it’s worn openly, with an air of self-congratulation.

It is, for working-class Americans today, the best of times, objectively—and the worst of times, subjectively. This is not because the spreadsheets are wrong, but because we fail to count the things that history records in tone, not totals—but rather things like mood, myth, and cultural resolve.

The Service Economy

According to the most recent data available from the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics, nearly four out of five Americans work in the service sector.15 For most Americans in most states, that means retail, fast-food, or some other smile-for-hire job located at the end of a check-out line.16 It’s a kind of work where labor isn’t just accomplished, it’s seen—performed under the soft surveillance of the American customer. So, beneath inflation charts and unemployment rates, if you want to understand the feelings side of the postindustrial economy—you might start with tipping.

It is, today, perhaps our most American habit—tipping for service; whether it be good, bad, or not provided. In restaurants, hair salons, and hotel lobbies, Americans tip over a hundred billion dollars a year—indeed, more than any other country on earth, and more than all of them combined.17 We tip cab drivers and pool cleaners and dog groomers and coat checkers. We tip the doorman on the way in, the bellhop on the way up, and the concierge on the way out. Americans tip so much that, as one European put it—the whole “approach [has become] completely deranged and out of control.”18

However, it wasn’t always this way. In fact, for much of the early 20th century, it was Americans who mocked Europeans for tipping—seeing it as smug, corrupt, and born of feudal etiquette.19 States such as Iowa, South Carolina, and Tennessee—among others—outlawed the practice entirely20; and wherever it remained legal, businesses proudly posted signs that read “No Tipping Allowed.”21 Some hotels even installed “servidors”—a two-way drawer that opened from hallway and room—so staff could deliver laundry without being seen, and without being tipped.22 As the author William R. Scott, in a book-length critique, put it in 1916:

In an aristocracy a waiter may accept a tip and be servile without violating the ideals of the system. In the American democracy to be servile is incompatible with citizenship … Every tip given in the United States is a blow at our experiment in democracy … Tipping is the price of pride. It is what one American is willing to pay to induce another American to acknowledge inferiority.

Somewhere along the way, however—somewhere between the Marshall Plan and the first McDonald’s Happy Meal—the parts reversed; and we became the punchline. It became the Americans who tipped like royals—and the Europeans who saw it as such.

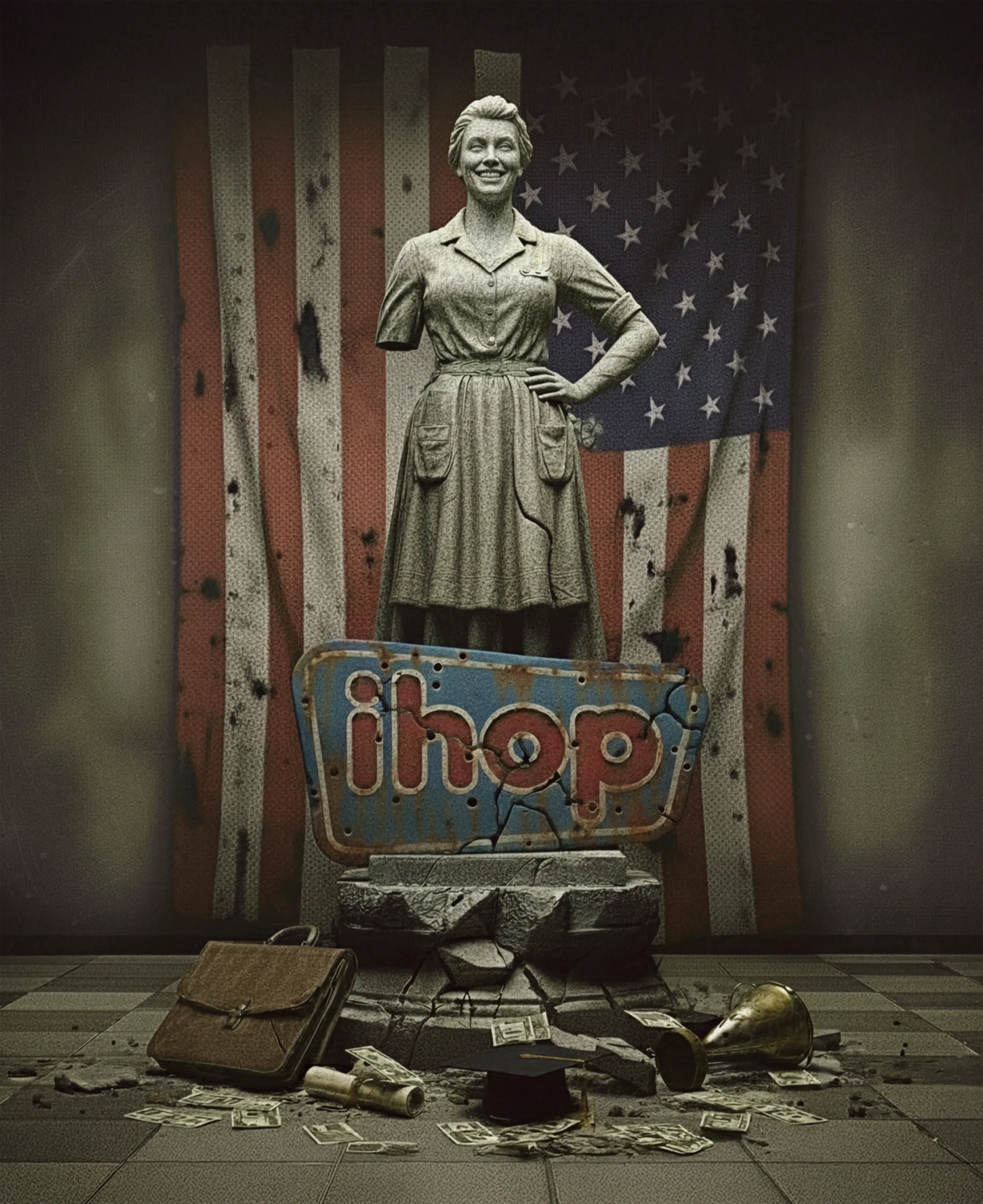

It was during this time that the gesture was institutionalized—not of custom or conscience—but because the Pullman Company, the National Restaurant Association, and eventually big tech sold it as part of the deal.23 Lobbying congress, adding tip lines to receipts and making feudalism feel American—if you’re the one tipping.24 Because on the other end—where the customer is always right—yes, the tip is now expected and yes, it is now appreciated; but gratuity has never been the same thing as respect and especially not when, for most working-class Americans, IHOP has become the least humiliating option.

The Status Economy

We are signaling obsessed, hierarchy calibrated social apes. All of us, according to author Will Storr in The Status Game, walk around like buzzed-up antennas—attuned to the faintest frequency of admiration or disdain, gossip, or snicker.25 Given that for most of human history, it wasn’t guns, germs, or steel that mattered most; it was access to the cooperative networks and high-yield alliances of a species where insiders eat first and the gates are closely guarded. And so what governs our decisions—above all else, even when no one’s watching—is the paranoia of social scrutiny. In other words, it’s a cost-benefit analysis where the material outcome barely matters and utility is downstream of reputational impact.

Absent this understanding of human behavior, very little of it makes sense; a core theme in the work of the early 20th century economist Thorstein Veblen, whose concept of “conspicuous consumption” describes how people often consume products they don’t need—or even want—in order to flaunt status and social class.26 Luxury watches that tell time worse, minimalist chairs you can’t sit on are purchases where the high price is the point.

Of course, it is no major insight to say that people buy things to show off. The anthropological record is rich with lavish feasts and displays of abundance. The famous “potlatch ceremonies” of Pacific Northwest Indian tribes, for example, involved burning immense stores of wealth—copper shields, hand-carved canoes that took years to build, blankets, oil, and food—generations of accumulated capital, in a single afternoon; just to signal status.27

But what about meditating, carrying around a well-worn copy of The New Yorker in your back pocket, or believing in climate change? Veblen’s brilliance was seeing that even our quietest preferences are currency in a market economy of social prestige. As British philosopher Dan Williams puts it:

Much cognition is competitive and conspicuous. People strive to show off their intelligence, knowledge, and wisdom. They compete to win attention and recognition for making novel discoveries or producing rationalizations of what others want to believe. They often reason not to figure out the truth but to persuade and manage their reputation. They often form beliefs not to acquire knowledge but to signal their impressive qualities and loyalties.

When people are angry, it’s rarely about money. It’s about being looked down on.

It’s the kind of signaling that thrives in what sociologists call “post-material economies” such as contemporary America.28 Because in a society maxed out on comfort—where even the ultrawealthy can’t buy a better Netflix or a softer couch—the only lines left to draw are ideological; and social distinction becomes the new class war. The rub, however, is that unlike the peacock’s tail—a hard- to-fake signal, metabolically costly, and policed by survival—immaterial prestige hierarchies are cultural inventions; often arbitrary, often performative, and almost always enforced from the top down. In other words, social prestige isn’t earned—it’s distributed by those who already have it. As social scientists Johnston and Baumann described in a 2007 paper:

The dominant classes affirm their high social status through consumption of cultural forms consecrated by institutions with cultural authority. Through family socialization and formal education, class‑bound tastes for legitimate culture develop alongside aversions for unrefined, illegitimate, or popular culture.29

The elite don’t just consume goods. They consecrate tastes, turning culture into a class barrier such that status is socially assigned rather than materially demonstrated. French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu called it symbolic capital—where opinions double as vocabulary tests and entry fees for membership into the aristocracy.30 As Princeton’s Shamus Khan explains, “Culture is a resource used by elites to recognize one another and distribute opportunities on the basis of the display of appropriate attributes.”31

Observing today’s ruling class, social psychologist Rob Henderson has coined the term “luxury beliefs,” arguing that the experts, the celebrities, and the institutions are all fluent in the same woke-speak, and by their material abundance can afford to focus almost exclusively on social justice issues that, ensconced in their gated communities, have no effect on their own luxurious lives (nor those of the people they profess to be helping).32

The words turn and turn again—testing for status, enforcing the pecking order.33 And now, just as working-class Americans born in the industrial economy once rejected cash tips—those born in the culture-capital economy don’t want the tip either. They want respect. The redneck reluctance to simply “trust the experts” or pronounce it “people of color” instead of “colored people” isn’t about bigotry or Bible verses or disinformation—it’s about refusing the role of grateful recipient in someone else’s moral theater. It’s not anti-intellectualism or anti-love and kindness. It’s anti-elitism.

A culture that sanctifies college as the gateway to full citizenship, over time corrodes the foundations of democratic life.

How is it that a born-rich multibillionaire has become the standard-bearer for the working class? It’s because his favorite food is McDonald’s; and to Nancy Pelosi, George Clooney, and my high school guidance counselor—Trump is trash. They see him the same way they see trailer park America—as tacky, ignorant, and disposable; always on the lowborn side of the tip. It’s a feeling well-known in union organizing circles.34 That when people are angry, it’s rarely about money. It’s about being looked down on.

A New Nationalism

Culture can often be hard to think about because it doesn’t exist in the world of objects—it exists in the world as a perceptual experience. It has no mass, no edge, no location. It’s not made of things; it’s made of meanings—real, but not tangible.

The cultural backlash hypothesis, the status threat hypothesis, the social isolation hypothesis, the political alienation hypothesis, the nostalgic deprivation hypothesis—a growing body of scholarship has emerged to name and quantify the immaterial contours of twenty-first century populist discontent; all circling the drain of an old, half-remembered truth.35, 36, 37, 38, 39

For most of history, kings, philosophers, and statesmen took seriously the idea that civilizations depend on symbolic cohesion—on rituals, traditions, and agreed-upon fictions capable of domesticating our most socially inconvenient biological biases. They understood, whether by insight or instinct, that there’s something important about ceremony and uniform and national character. That propaganda isn’t all bad. That done right, good slogans make good citizens. And good citizens make great nations. As Gidron and Hall put it in a recent paper:

[I]ssues of social integration [must be taken] more seriously in studies of comparative political behavior. Such issues figured prominently in the work of an earlier era … but they fell out of fashion as decades of prosperity seemed to cement social integration.40

In the old economy it was simple. You had the rich, who lunched at steakhouses and voted Republican; the working class, who labored in factories and voted Democrat; and in between, the mass suburban middle class. When it came, the conflict was clear—members of the working class joining forces with progressive intellectuals to oppose the moneyed elite. Yet every once in a while, a new, revolutionary class of citizens comes along and scrambles the whole social order. In the late 20th century it was the scholastic king—and the new culture-laureate class. He is not merely an academic; he is society’s central planner, a warden of elite passage, and the face of the new American aristocracy; and as The New York Times columnist David Brooks put it:

If our old class structure was like a layer cake—rich, middle, and poor—the creative class is like a bowling ball that was dropped from a great height onto that cake. Chunks splattered everywhere.41

Outsourcing made economic sense, globalization was in large part inevitable, and cheap goods are always good politics—sure, fine. But for over fifty years now, neither political party has been able to solve the social problem of a postindustrial economy. And no American president has been able to tell a story good enough to replace the one previous generations called true. As sociologist Arlie Hochschild explained in a recent interview with The New York Times:

We keep looking for real policies. That’s not the thing. Trump offers a veneer of policies and a story, and we’ve got to tune in to the effect of that story on people who feel like the world’s melting and sinking … Because whatever the policies, these voters are following the story and the emotional payoff of that anti-shaming ritual. So we have to stop the story, reverse the story: Nobody stole your pride, we’re restoring it together.42

In the same way philanthropy never solves economic inequality, bigger and better information tips will never win the culture war—because it’s not about being rich or poor, stupid or smart; it’s about better than or worse than. And the only thing that can make a rich person feel worse than a poor person—or a smart person worse than a stupid one—is a national story written by poor people and stupid people too. It’s the sort of new nationalism that, in the past, has required several interconnected efforts.

The Bottom Line

Robert F. Kennedy, in March of 1968, in a speech at the University of Kansas, noted: “The gross national product can tell us everything about America except why we are proud that we are Americans.”43

Rubber in Akron. Meat in Chicago. Coal in Scranton. Steel in Gary. It used to be you knew a city by what it made—how it sounded, how it smelled. In 1950 Detroit was the richest city in the world—that’s right, the entire world.44 On Zug Island, they used to make the whole car, start to finish—iron ore mined and smelted on one end, parts shaped and assembled along the way, and a new Ford rolled off the line at the other—no imports, no one else. It was vertical integration—of work, of community, of pride.

But by the 1970s a new day had dawned, the old days were gone, and the unraveling had begun. Over half the manufacturing jobs moved elsewhere, a quarter of the population went too; and with whole neighborhoods left to rot, Detroit, once called “the Paris of the Midwest,” became one of the deadliest cities in the country.45, 46 From 1965 to 1974, homicides quintupled47; the central business district earned the name “zone of decay”; and businesses began installing bulletproof glass—floor to ceiling—to protect storefront clerks.

Just like that—two short decades transformed America’s motor city into America’s murder city. And burnt, bled, and bankrupt, the once shining example rolled out perhaps the saddest, most pitiful ad campaign in American history: “Say Nice Things About Detroit.”48

It’s not about being rich or poor, stupid or smart; it’s about better than or worse than.

The bottom line is this. Every new economy produces different winners and losers—it’s just the way it is. What happened in Detroit was, in many ways, what was expected. But when the losses came—when the bottom fell out for the millions of working-class Americans still there, still trying—it was treated not as a national obligation but as an unfortunate footnote to progress. Detroit was told to retrain, relocate, find a way to adjust—and when they failed, just like the people still living in Akron, Scranton, and Gary, they were humiliated, cast as mascots of ignorance and failure. The problem is that the ignorant and the failed far outnumber those who aren’t. And so, as Franklin Roosevelt said, it’s not “whether we add more to the abundance of those who have much” that matters—“it is whether we provide enough for those who have too little.”

Because when the empire falls—when the American experiment joins the long ledger of civilizations past, it won’t be at the hands of China or Russia or Al Qaeda or anyone else. We are the richest nation in the history of the world; no other society has ever wielded as much global influence; not even a coalition of all the world’s armies could best ours. “If destruction be our lot,” wrote a 28-year- old Abraham Lincoln, “we must ourselves be its author and finisher.”49 As “a nation of freemen, we must live through all time, or die by suicide.”

And if it comes to that—if we choose death; it won’t be about free trade or wages or unemployment rates any more than it was about taxes in 1776. Once again, it will be about respect.