Nuremberg: The Film, The Trial, The Verdict

Hermann Göring is a larger-than-life character who commands a big-screen presence both in real life and in cinematic representations. His latest portrayal, by the estimable Russell Crowe, captures this presence with notable fidelity.

Crowe plays Göring in all his official guises: Reichsmarschall, Luftwaffe chief, President of the Reichstag, Plenipotentiary of the Four-Year Plan, and Hitler’s designated successor (until the Führer revoked that status in the last days of the war and ordered Göring’s arrest for treason). Crowe’s performance is as convincing as his portrayal of Maximus Decimus Meridius in Ridley Scott’s 2000 film Gladiator. (See also Robert Pugh as Göring in the BBC series Nuremberg: Nazis on Trial, which highlights the more jovial side of the Reichsmarschall’s personality.)

The 148-minute PG-13 film, Nuremberg, directed and written by James Vanderbilt, also stars Rami Malek (who played Queen lead singer Freddie Mercury in the biopic Bohemian Rhapsody) as the official prison psychiatrist Dr. Douglas Kelley, and Colin Hans as Dr. Gustave Gilbert, official prison psychologist.

Un-historically, Gilbert appears in a tertiary role, with the entire film focus on the relationship between Göring and Kelley (credited to Jack El-Hai’s book The Nazi and the Psychiatrist), which is an odd paring because, in fact, Kelley left “after the first month of the trial and was succeeded by Major Leon N. Goldensohn for most of the rest of the trial,” an explanation on offer from Dr. Gilbert himself in his 1947 book Nuremberg Diary.

In the film, the two shrinks are juxtaposed as quarreling over who was going to profit from participation in the trial of the century, departing the scene in anger. But in his Nuremberg Diary acknowledgments, Dr. Gilbert writes:

I am indebted to Colonel B. C. Andrus, prison commandant, and Dr. Douglas M. Kelley, prison psychiatrist for the first two months, for facilitating my assignment to the Nuremberg jail with free access to all the prisoners from the very beginning of my stay there.

Gilbert’s book is a compendium of deep insights into politics, Nazism, war, conflict, personality, free will and moral culpability, and the nature of good and evil. There are also amusing insights like this one from the prison commandant Colonel Andrus: “When Göring came to me at Mondorf, he was a simpering slob with two suitcases full of paracodeine. I thought he was a drug salesman. But we took him off his dope and made a man of him.” I have a hardback first edition that I picked up at a used-book sale at Glendale College in the 1980s, where I was teaching at the time and researching the history of conflict, violence, and war.

Some notable excerpts from Dr. Gilbert’s book:

In our conversations in his cell, Göring tried to give the impression of a jovial realist who had played for big stakes and lost and was taking it all like a good sport. Any question of guilt was adequately covered by his cynical attitude toward the “justice of the victors.” He had abundant rationalizations for the conduct of the war, his alleged ignorance of the atrocities, the “guilt” of the Allies, and a ready humor which was always calculated to give the impression that such an amiable character could have meant no harm. Nevertheless, he could not conceal a pathological egotism and inability to stand anything but flattery and admiration for his leadership, while freely expressing scorn for other Nazi leaders.

Göring’s ego was on full display over the weekend of March 16-17, 1946, as evidenced in this reflection by Gilbert after visiting the prisoner’s cell:

Göring was very tired from the strain of the past three days’ testimony. His defense being almost completed, he was already moodily brooding over his destiny and speculating on his role in history. Humanitarianism had become a thorn in his side, and he cynically rejected it as a threat to his future greatness. The empire of Genghis Kahn, the Roman Empire, and even the British Empire were not built up with due regard for principles of humanity, he expostulated with weary bitterness—but they achieved greatness in their time and have won a respected place in history. I reiterated that the world was becoming a little too sophisticated in the 20th century to regard war and murder as the signs of greatness. He squirmed and scoffed and rejected the idea as the sentimental idealism of an American who could afford such a self-delusion after America had hacked its way to a rich Lebensraum [living space] by revolution, massacre, and war [a reference to America’s own history of extermination of Native Americans, of which Göring was familiar].

When his testimony was over, Göring “made an outright bid for applause for his performance,” asking Gilbert “Well, I didn’t cut a petty figure, did I?” Gilbert penned in his notes: “He couldn’t help admiring himself, and paused for a moment to do so. Yes, he was quite satisfied with his figure in history. ‘Why, I bet even the prosecution had to admit that I did well, didn’t they? Did you hear anything?’” Gilbert concluded of Göring, “The test of his medieval heroism was admiration by the enemy. I shrugged my shoulders.”

Another un-historical segment in the Nuremberg film has Dr. Kelley visiting Göring’s wife and daughter, Emmy and Edda, when in fact it was Dr. Gilbert who “visited Frau Emmy Göring at the house in the woods of Sackdilling near Neuhaus, to which she had retired with her daughter and niece after her release from custody” (he devotes a chapter in Nuremberg Diary to the visit). (Why filmmakers take such unnecessary license with historical truths is beyond me.) Emmy Göring had plenty to say about how “disgraceful to us to see how many Germans are saying they never really supported Hitler, that they were forced into the Party, there is so much hypocrisy, it is sickening!” She raged about Hitler’s order to execute the entire Göring family (“can you imagine that madman ordering that child shot?” pointing to Edda), then when her daughter was not present addressed the topic of atrocities:

She told how she had asked Himmler to let her go and see Auschwitz concentration camp, because she had received so many letters saying that things were not quite as they should be. As the first lady of the land she wanted to be convinced that everything was in order. Himmler wrote a polite letter, but told her not to meddle in things that were no concern of hers.

As for the unprecedented concept of the Nuremberg trial itself, Göring told Gilbert “I still don’t recognize the authority of the court,” adding:

Anything that happened in our country does not concern you in the least. If 5 million Germans were killed, that is a matter for Germans to settle; and our state policies are our own business.

Clearly the court begged to differ, and to drive home the point Göring and the others were subjected to George Stevens’ The Nazi Concentration Camps film footage from, for example, Nordhausen:

Gilbert took notes as he observed the Nazi leaders reacting to the horrors on the screen:

Fritzsche already looks pale and sits aghast as it starts with scenes of prisoners burned alive in a barn… Keitel wipes brow, takes off headphones… Göring supported his head on his hand and looked tired, then stirred uneasily in the doc and changed position. Funk covers his eyes, looks as if he is in agony, shakes his head… Ribbentrop closes his eyes, looks away… Sauckel mops brow… Frank swallows hard, blinks eyes, trying to stifle tears… Funk now in tears, blows nose, wipes eyes, looks down… Frick shakes head at illustration of “Violent death”—frank mutters “Horrible!”… Speer looks very sad, swallows hard… Defense attorneys are now muttering, “For God’s sake—terrible.”

In addition to employing the now discredited Rorschach ink-blot test in hopes of evoking deep personality characteristics and hidden motives of his charges (in the film the Nazis see Jews, vaginas, and Jewish vaginas), Gilbert administered the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale and found the following results (100 = average, 115 = one standard deviation above average, or better than 84% of test takers, 130 = two standard deviations above average, or better than 98% of test takers, and 145 = three standard deviations above average, or better than 99.9% of test takers):

|

Name |

IQ Score |

|

Arthur Seyss-Inquart |

143 |

|

Hermann Göring |

138 |

|

Karl Doenitz |

138 |

|

Frans von Papen |

134 |

|

Hans Frank |

130 |

|

Joachim von Ribbentrop |

129 |

|

Wilhelm Keitel |

129 |

|

Albert Speer |

128 |

|

Alfred Jodl |

127 |

|

Walther Funk |

124 |

|

Fritz Sauckel |

118 |

|

Ernst Kaltenbrunner |

113 |

As Gilbert concluded:

The IQs show that the Nazi leaders were above average intelligence, merely confirming the fact that the most successful men in any sphere of human activity—whether it is politics, industry, militarism, or crime—are apt to be above average intelligence. It must be borne in mind that the IQ indicates nothing but the mechanical efficiency of the mind, and has nothing to do with character or morals, nor the various other considerations that go into an evaluation of personality. Above all, the individual’s sense of values and the expressions of his basic motivation are the things that truly reveal his character.

Even more insightfully, Gilbert adds:

However, a social movement as far-reaching and catastrophic as that of Nazism cannot be adequately analyzed and understood merely in terms of the individual character traits of its leaders. A realistic psychological approach requires an insight into the total personalities in interaction in their social and historical setting. The Nuremberg Trial afforded an ideal opportunity for such a study.

Here, for example, is one of the most poignant exchanges Gilbert had with Göring about the politics of war:

Göring: Why, of course, the people don't want war. Why would some poor slob on a farm want to risk his life in a war when the best that he can get out of it is to come back to his farm in one piece? Naturally, the common people don't want war; neither in Russia, nor in England, nor in America, nor for that matter in Germany. That is understood. But, after all, it is the leaders of the country who determine the policy and it is always a simple matter to drag the people along, whether it is a democracy, or a fascist dictatorship, or a parliament, or a communist dictatorship.

Gilbert: There is one difference. In a democracy the people have some say in the matter through their elected representatives, and in the United States only Congress can declare wars.

Göring: Oh, that is all well and good, but, voice or no voice, the people can always be brought to the bidding of the leaders. That is easy. All you have to do is tell them they are being attacked, and denounce the pacifists for lack of patriotism and exposing the country to danger. It works the same way in any country.

That is an accurate description of the world before World War II. After, when the world came to grasp the full extent of the Nazi genocide, an International Law Commission was born out of the Nuremberg trials of German war criminals for their “crimes against humanity,” which it defined as follows:

Murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation and other inhumane acts done against any civilian population, or persecutions on political, racial, or religious grounds, when such acts are done or such persecutions are carried on in execution of or in connection with any crime against peace or any war crime.

This was based on a new set of legal and moral principles (from Nuremberg Trial Proceedings Vol. 1. Charter of the International Military Tribunal) such as: Principle 1: “Any person who commits an act which constitutes a crime under international law is responsible therefore and liable to punishment.” And Principle II: “The fact that internal law does not impose a penalty for an act which constitutes a crime under international law does not relieve the person who committed the act from responsibility under international law.”

From the start, Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson insisted on a fair trial for all, noting in his opening statement “To pass these defendants a poisoned chalice is to put it to our own lips as well.” The Nuremberg trials were one of the greatest contributions to expanding the moral sphere of justice on a global scale, signaling to dictators and demagogues everywhere that the world was watching and would hold them accountable for their actions.

Like most of the Nazis at the Nuremberg trial, Göring’s defense was that he was innocent by virtue of the fact that he was only following orders. Befehl ist Befehl—orders are orders—is now known as the Nuremberg defense, and it’s an excuse that seems particularly feeble in a case like Göring’s and the other Nazi leaders in the doc. “My boss told me to kill millions of people so—hey—what could I do?” is not a credible defense, but here are their pleas as documented by Gilbert:

Joachim von Ribbentrop, Foreign Minister: “We were all under Hitler’s shadow.”

Ernst Kaltenbrunner, Chief of Heinrich Himmler’s Security Headquarters: “I do not feel guilty of any war crimes. I have only done my duty as an intelligence organ, and I refuse to serve as an ersatz for Himmler.”

Hans Frank, Governor-General of occupied Poland: “I regard this trial as a God-willed world court, destined to examine and put to an end the terrible era of suffering under Adolf Hitler.”

Field Marshal Keitel, Chief of Staff of the High Command of the Wehrmacht: “For a soldier, orders are orders.”

Admiral Doenitz, Grand Admiral of the German Navy and Hitler’s successor: “None of these indictment counts concerns me in the least.”

In the epilogue to Nuremberg Diary, Gilbert records the 21 Nazi defendants’ final statements, including this gem exchange between Göring and von Papen:

Göring deserted Hitler and made a grandiose protestation of his own innocence, calling upon God and the German people as witnesses to the fact that he had acted out of pure patriotism. This hypocrisy infuriated von Papen so much that he came over and attacked Göring at lunch, demanding furiously, “Who in the world is responsible for all this destruction if not you?! You were the second man in the State! Is nobody responsible for any of this?” He waved his arms at the ruins of Nuremberg visible through the lunchroom windows.

Goering folded his arms cockily and smirked into von Papen’s face: “Well, why don’t you take the responsibility then? You were Vice-Chancellor!”

Most of the other defendants acknowledged that there had been horrible crimes committed, but claimed that they had individually acted in good faith according to the standards of their respective positions and professions. The generals had only followed orders; the admirals had done no more than other admirals; the politicians had only worked for the Fatherland; the financiers had only attended to business.

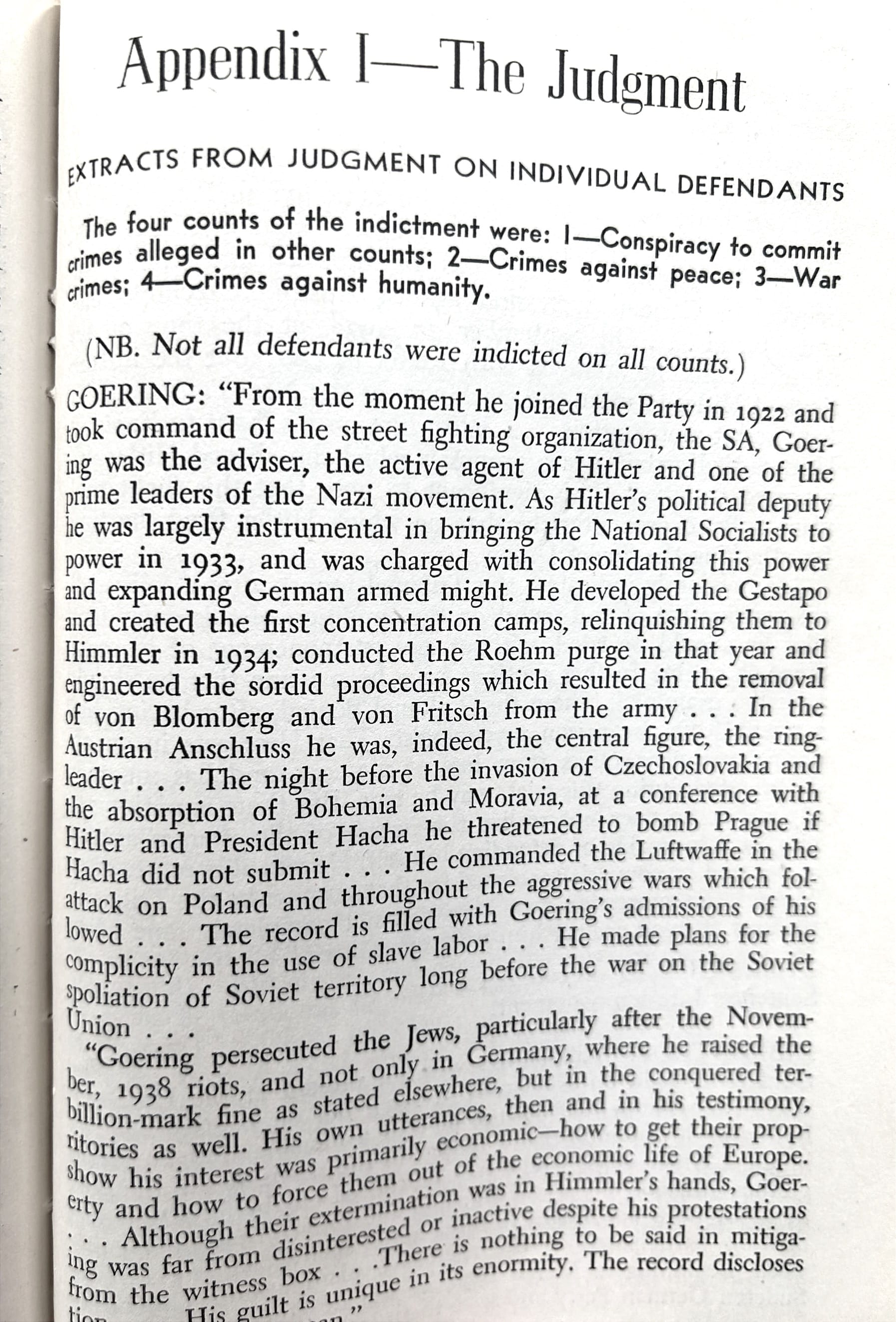

The four counts of the indictment against Göring and the others were (1) Conspiracy to commit crimes alleged in other counts; (2) Crimes against peace; (3) War crimes; (4) Crimes against humanity.

Göring’s verdict was “GUILTY on all 4 counts. Sentence: Death by hanging.” Here is Gilbert’s summary of Göring’s conviction:

Unbelievably—given the draconian measures of prisoner monitoring after the head of the German Labour Front, Robert Ley, died by suicide in his cell before the trial even began—Göring cheated the hangman’s noose, chomping down on a vial of cyanide in his mouth, somehow smuggled into his cell as the executioners began their preparation for carrying out the court’s sentence.

To this day no one knows who aided the Reichsmarschall’s escape from justice. The film’s artistic interpretation is that he made it appear by “magic”—thereby tying the ending of the film to the beginning with Dr. Kelley making a coin disappear and reappear as he performs magic for a comely woman on the train ride to Nuremberg in the film’s awkward opening scene. The likeliest explanation is that Göring charmed one of the guards into slipping him a capsule at the last moment; given his considerable personal influence over millions of ordinary Germans to commit extraordinarily evil crimes against humanity, it doesn’t seem fanciful that he cajoled some neophyte guard into helping him evade the hangman’s noose.

In the end, none of the convicted Nazi were surprised by their sentences, least of all Göring, who admitted to Gilbert that he expected the death penalty from the start, “and was glad that he had not gotten a life sentence, because those who are sentenced to life imprisonment never become martyrs. But there wasn’t any of the old confident bravado in his voice. Göring seems to realize, at last, that there is nothing funny about death, when you’re the one who is going to die.”

Göring’s observation, along with the lessons from the film itself—well worth seeing in a theater on a big screen—tells an important story our society seems all too ready to forget these days, namely that in the end if justice does not prevail then evil will.