Outsourcing Our Memory: How Digital Tools Are Reshaping Human Thought

Every year on my birthday, my phone would light up with messages from friends, acquaintances, old coworkers, distant relatives—all offering quick well-wishes. The notes weren’t particularly personal, but I found something reassuring about being remembered. Then, one year, I changed my social media privacy settings to see who would remember without the digital nudge. When no notifications came, I felt a pang of sadness at being forgotten. I understood then that my birthday no longer lived in anyone’s memory. Instead, it lived on a digital cloud governed by algorithms; without pushed out notifications, I was invisible. That year, other than birthday wishes and presents from my closest family members, the only birthday greeting I received was a postcard from my dentist, wishing me a “healthy and happy year ahead” and reminding me that I was due for a cleaning.

This experience reveals a deeper truth: as we increasingly depend on digital tools to remember for us, we risk forgetting something very important. Memory is more than data stored somewhere—it’s what makes us who we are. It dictates our perspective on the world, our feelings, actions, and reasoning. It is the backbone of identity, supporting our sense of continuity and coherence. Memory helps us create meaning, make sense of the present, and predict the future based on past experiences and knowledge. We each hold both personal memories, and shared cultural and historical ones. Most of us fear losing them, whether due to neurological illness, data loss, or the mere passage of time. Without our memories, would we still be who we are?

Memory is more than data stored somewhere—it’s what makes us who we are.

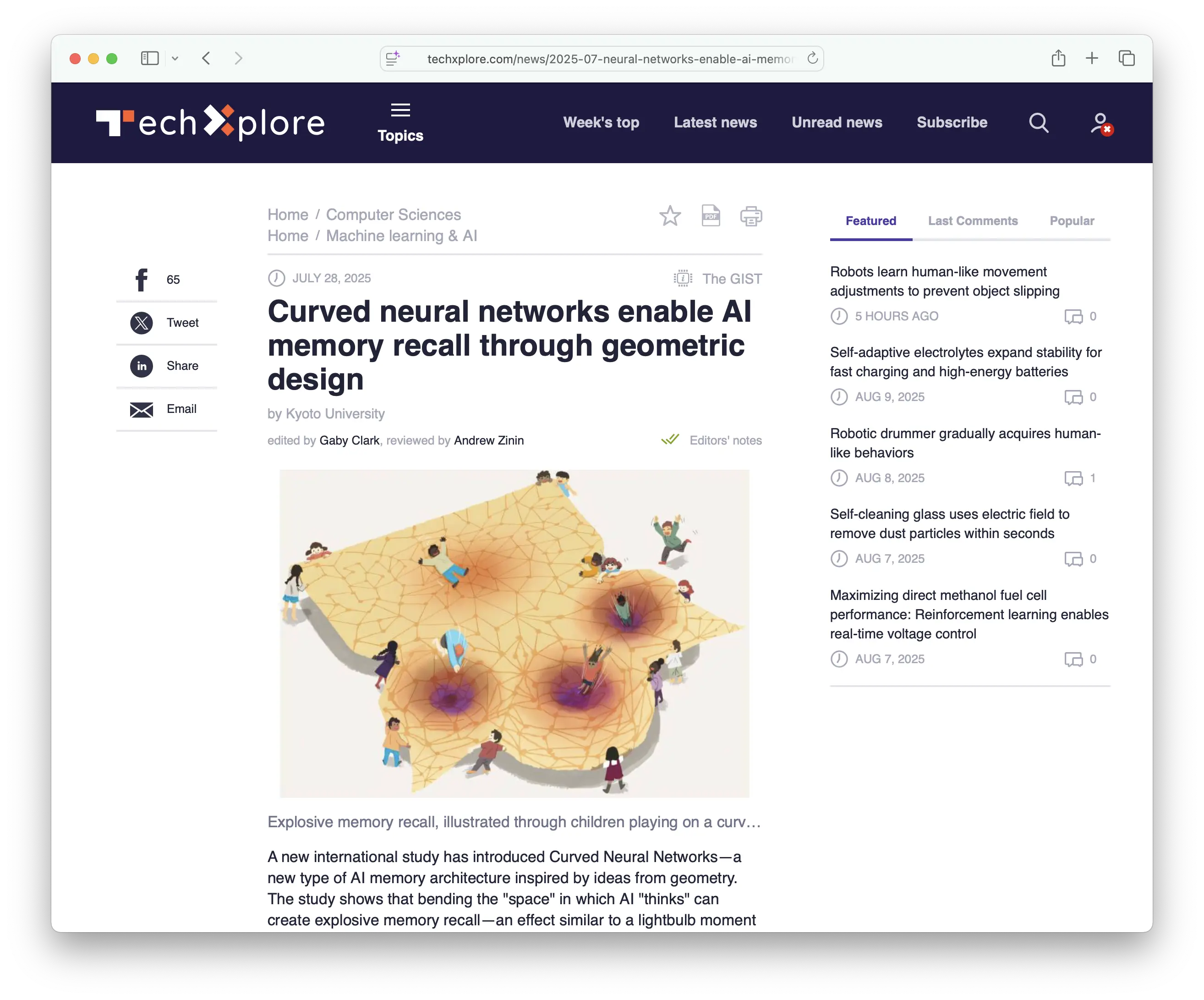

Last week, researchers from Kyoto University, the University of Sussex, BCAM, and Araya Inc. published a study in Nature Communications about Curved Neural Networks, a new AI memory architecture that uses geometric design to mimic how the human brain recalls memories. By allowing AI to “bend” its computational space, it can simulate an effect similar to a human “lightbulb” moment through “explosive memory recall.” This could lead to AI systems with faster, more human like memory recall for applications ranging from robotics to brain-inspired computing. However, as more of our memories migrate to machines, will it fundamentally change us?

Consider how you access your autobiographical memory. How much of it is reflected in the thousands of images you’ve captured on your smartphone? Or saved emails and private messages you can’t bring yourself to delete? Then there are sources of external memory: How many phone numbers do you remember? How often do you rely on GPS to navigate? How frequently do you turn to Google or ChatGPT to recall a fact, event, or concept? Even when a restaurant doesn’t automatically suggest the tip amount for you, can you do it in your head or do you need the calculator on your phone?

It’s clear that our relationship with memory has been undergoing a profound transformation. Are we enhancing our minds, or eroding our capacity for deep learning and critical thought?

Tools aren’t inherently harmful. They are extensions of human capability. From the moment a primitive hominid used a bone as a weapon, as dramatized in 2001: A Space Odyssey, tools marked the dawn of a breakthrough in human intelligence. Modern digital tools do more than extend physical capability for memory; they transform how we think, learn, and create meaning.

Are we enhancing our minds, or eroding our capacity for deep learning and critical thought?

The phenomenon of relying on external aids to manage cognitive tasks is known as cognitive offloading, which reduces the demand on our brain. It’s not new. We’ve always done it, with notebooks, to-do lists, calendars, and address books. But the digital age has dramatically amplified this process. Modern digital tools, especially those powered by Large Language Models (LLMs), are not merely digital filing cabinets; they are our active partners, helping to interpret data, connect concepts, and spark original thinking—functioning much like an auxiliary brain.

In some ways, cognitive offloading is not dissimilar to transactive memory, proposed by psychologist Daniel Wegner to describe how memory is distributed across individuals and systems so that we do not need to rely exclusively on our own memories, but rather can offload some of them to our social networks. For example, one’s romantic partner might remember certain things that you struggle to recall, and vice versa. Or your sibling might remind you of your parents’ pending anniversary. Today, their digital counterparts increasingly play that role.

A 2011 study in Science, however, reported that this process of cognitive offloading or transactive memory can negatively impact on our own memory capacity, as we are less likely to remember or internalize information if we think we’ll be able to access it elsewhere. The researchers call this the Google Effect. “The Internet has become a primary form of external or transactive memory, where information is stored collectively outside ourselves,” the researchers concluded.

This was nearly 15 years ago.

Since then, our dependence on external memory systems has increased exponentially, often at the expense of internalizing knowledge. AI-powered tools can now instantly provide answers to even the most complex questions, analyze data, and summarize articles—even entire books or the lifetime corpus of famous authors.

It’s easier than ever to be able to learn about whatever the new thing we are seeking out is, but the mechanism of attaining answers has shifted. No longer do you have to sift through Google pages—let alone bound books—to get information, a process through which you’re likely to find more context and develop deeper understanding. AI tools allow you to skip a lot of steps and get answers immediately, though often without the benefit of full context or source transparency—something that we ought to be demanding.

There are popular apps that advertise how you can gain knowledge quickly by “reading” abridged books—which are summarized by AI. Certainly, it’s an efficient way to absorb some key points quickly, but does it not miss the depth available only in reading the full text? Does it not skip over the mental process required to truly grasp the ideas within the works? We often learn best by struggling with complexity. Indeed, what exactly does happen to our brain when we rely so heavily on offloading? Neuroscience provides some clues.

Memory isn’t a static system similar to document storage in a filing cabinet—it’s a dynamic process by which the brain encodes, stores, and retrieves information, and is shaped by attention, emotion, sleep, context, and more. Thanks to neuroplasticity, the brain’s remarkable ability to rewire itself, we can change the structure and function of neural circuits through repeated use. Learning, for example, strengthens the connections between neurons across a network of brain regions, including the hippocampus (which helps form new memories), the amygdala (which invests them with emotional significance), and the prefrontal cortex (which manages attention and decision-making). A seminal study led by Eleanor Maguire at University College London found that London taxi drivers who’ve rigorously memorized city maps had an enlarged region of the hippocampus compared to the general population. The findings also suggested that when memory demands decrease, the hippocampus may physically shrink.

When we stop engaging our cognitive faculties, those neural pathways can weaken, making recall and retention more difficult over time.

In short, memory is not just what you know; it’s what your brain is actively building, moment by moment. When we stop engaging our cognitive faculties, those neural pathways can weaken, making recall and retention more difficult over time. Research has shown that relying on external tools to handle mental tasks such as memorization can hinder our long-term ability to retain information, as well as reducing our capacity for formation of new memories.

Recent work by Microsoft Research and Carnegie Mellon University focused on 319 knowledge workers and their use of generative AI tools. It found that those workers who frequently used generative AI tools and placed more confidence in them had experienced a decline in critical thinking skills, as they became more reliant on AI for problem-solving. Over-reliance on such tools tends to lead to more passive consumption of information, and less scrutiny of outputs. Individuals also lose the opportunity to practice and develop their own cognitive skills, leading to cognitive dependence.

The level of trust towards such memory aids seems to play a significant role when it comes to how often we rely on them to offload memory tasks, and while long-term performance is affected, offloading can actually enhance short-term performance. This is particularly useful given that our short-term storage capacity is 3 to 5 chunks of information (recently shortened from the famous 5 to 7 chunks), on average.

In 1885, the German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus developed a memory theory called the Forgetting Curve, tracing the exponential rate at which new information tends to be forgotten if there’s no effort made to retain it. It turns out that we begin to forget information almost immediately, but recall exercises can help us prevent this loss. Without such efforts, we would likely forget around 90 percent of new information within a week. That’s why you might pass an exam you’ve studied for the night before, but you aren’t likely to recall much the following week. Or why we forget languages we don’t practice.

Yet we should not view our forgetfulness as an entirely negative process. If we retained all memories, our brains would be flooded with unnecessary information, rendering them highly inefficient at processing information. That is why evolutionary pressures also wired us to forget things. We have specialized neural systems actively erasing or suppressing memory traces to keep what’s stored relevant and reserving space for more important information. A 2017 study by Blake Richards and Paul Frankland published in Neuron, shows that the brain actively prunes existing memories so that it can make room for more relevant information. The researchers proposed that “memory transience” is necessary in a “world that is both changing and noisy” and argued that forgetting is adaptive because it allows for more behavioral flexibility.

If we retained all memories, our brains would be flooded with unnecessary information, rendering them highly inefficient at processing information.

Their claim is further boosted by a study published in Nature, which found that boosting hippocampal neurogenesis after training caused mice to forget a learned platform location in a water maze, but helped them learn a new location more quickly. Conversely, suppressing neurogenesis preserved the original memory but impaired the ability to adapt to the new platform location, showing that forgetting can facilitate learning in changing environments.

In a similar way, offloading our memories to digital tools could ensure that we’re optimizing our memory space. The overall impact depends on how we use these tools: Are they replacing the act of memorizing and learning altogether, or are they simply freeing us to allocate more mental resources for other forms of memory?

In ancient Greece, students of philosophy and rhetoric were trained to memorize long speeches and texts using sophisticated mnemonic techniques. In medieval Europe, monks meticulously copied manuscripts by hand, and scholars often committed vast portions of religious and philosophical texts to memory. In many Indigenous and oral cultures, knowledge of medicine, law, and ancestry was passed down entirely through storytelling and memorization, often over generations. Before the invention of the printing press in the 15th century, and long before the internet, much of human knowledge had to be carried internally. People tended to carry more knowledge in their heads, but there was also far less knowledge to carry. But over the centuries we’ve accumulated a staggering amount of information, most of which stored in books, and increasingly in computers and computerized devices.

At this point, however, there’s no going back, so the question isn’t whether we should offload memory but when we should do it. By delegating certain trivial or repetitive information elsewhere, we can free up cognitive resources for more creative, complex, or strategic thinking. Memorizing phone numbers or addresses is probably not the best use of our bandwidth. Reducing rote memorization and offloading trivial data frees up mental bandwidth to pursue complex, creative cognitive tasks, or strategic thinking—human faculties that no machine can fully replicate yet (AGI could change that). Instead of remembering every historical date, we might focus on understanding the causes and consequences of major events or political shifts.

Emerging AI “second brain” technologies promise cognitive augmentation by externalizing personal memory. At the same time they raise new ethical and philosophical questions about identity, dependence on machinery, and the nature of knowledge.

There are several companies promising to offer applications that would memorize everything we encounter on a daily basis and allow us to easily recall such things simply by asking questions like: “What did the guy I met with on Wednesday say about flesh-eating robots?” or “What brilliant idea for taking over the world did John Smith reference at our meeting?” The possibilities are endless. Such a tool would act as an extension of our own memories—not just of facts, but of our lives themselves.

We already have AI assistants that prepare meeting summaries and notes, wearables that provide contextual reminders and information overlays, apps that organize notes and interlink ideas on our behalf (like Obsidian), and AI smart glasses that can help us recognize faces.

In the fields of medicine or law, memory-based tools can be particularly consequential. Being able to quickly tap into data, including a doctor’s own notes, and analyze it, can lead to a faster and more accurate diagnosis. The ability to precisely recall precedents or case details and make instant connections can affect legal reasoning and the ability to try a case.

Memory isn't just about recall of data … It's also necessary for pattern recognition, and diagnostic reasoning.

However, memory isn’t just about recall of data. It’s also necessary for pattern recognition, and diagnostic reasoning. If too much is relegated to auxiliary tools, it might hinder the intuitive decision-making process, where experience and memory form an important backbone. For a surgeon, for instance, repetition and internalized procedure recall are critical. For a lawyer, being able to recall certain precedents internally is necessary for persuasive reasoning and rhetorical strategy, especially in making objections that can exclude harmful evidence or testimony or form the ground for appeals, should the verdict go against their client.

There’s another serious concern around offloading our memories to our smartphones or the cloud that extends beyond cognitive or psychological effects. A major issue is privacy and security, which is becoming an increasingly pressing issue as more sensitive information is being stored outside of our own minds. Consider medical consultations with Dr. ChatGPT, or that late night therapy session when no one else was available to hear you out. Add to that diet logs stored in apps, or symptom trackers, search histories, GPS location data, conversations, photos and videos, and so on. Not only is your digital memory footprint trackable, but it can be used to analyze almost everything about you.

Unfortunately, data breaches are not uncommon. Neither is device loss or theft. In her book, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, Shoshana Zuboff writes that surveillance capitalism “unilaterally claims human experience as free raw material for translation into behavioural data [which] are declared as a proprietary behavioural surplus, fed into advanced manufacturing processes known as machine intelligence, and fabricated into prediction products that anticipate what you will do now, soon, and later.”

User data on Facebook or Google isn’t merely used to provide a better user experience, she argues, it is treated as raw material from which tech companies can infer personal details and influence or manipulate behavior without sufficient oversight.

When memory is outsourced, it may also be commodified.

We may not be able to completely prevent data breaches, or monitoring, but there are some steps we can take to protect our digital memories. These include using apps and storage solutions that encrypt data, using personal AI assistants that process requests locally versus keeping them on a server, storing especially sensitive or important memories offline—ideally with encrypted backups, considering using anonymous accounts for certain late-night conversations with chatbots, even air-gapping security information and systems.

We also need to advocate for stronger data protection laws, such as “the right to be forgotten” which allows users to request permanent deletion of their digital memories from platforms. As well, we need to enforce transparency mandates so that data processors (especially within the expanding AI realm) have to clearly explain which data are collected, stored, and shared. Ideally, any such systems—just like the human brain—could, by design, also “forget” data, not just remember it.

Our identities are built on the stories we remember and retell ourselves. Digital tools may allow us to better recall and play back our memories, but our role is to reflect on and analyze them. Digital time capsules can tell us what happened, but understanding what it all meant and how it felt—that’s a job for us humans. Machines don’t feel, or care. We do. So, ask yourself: What’s really worth remembering?