The Selective Rationality Trap

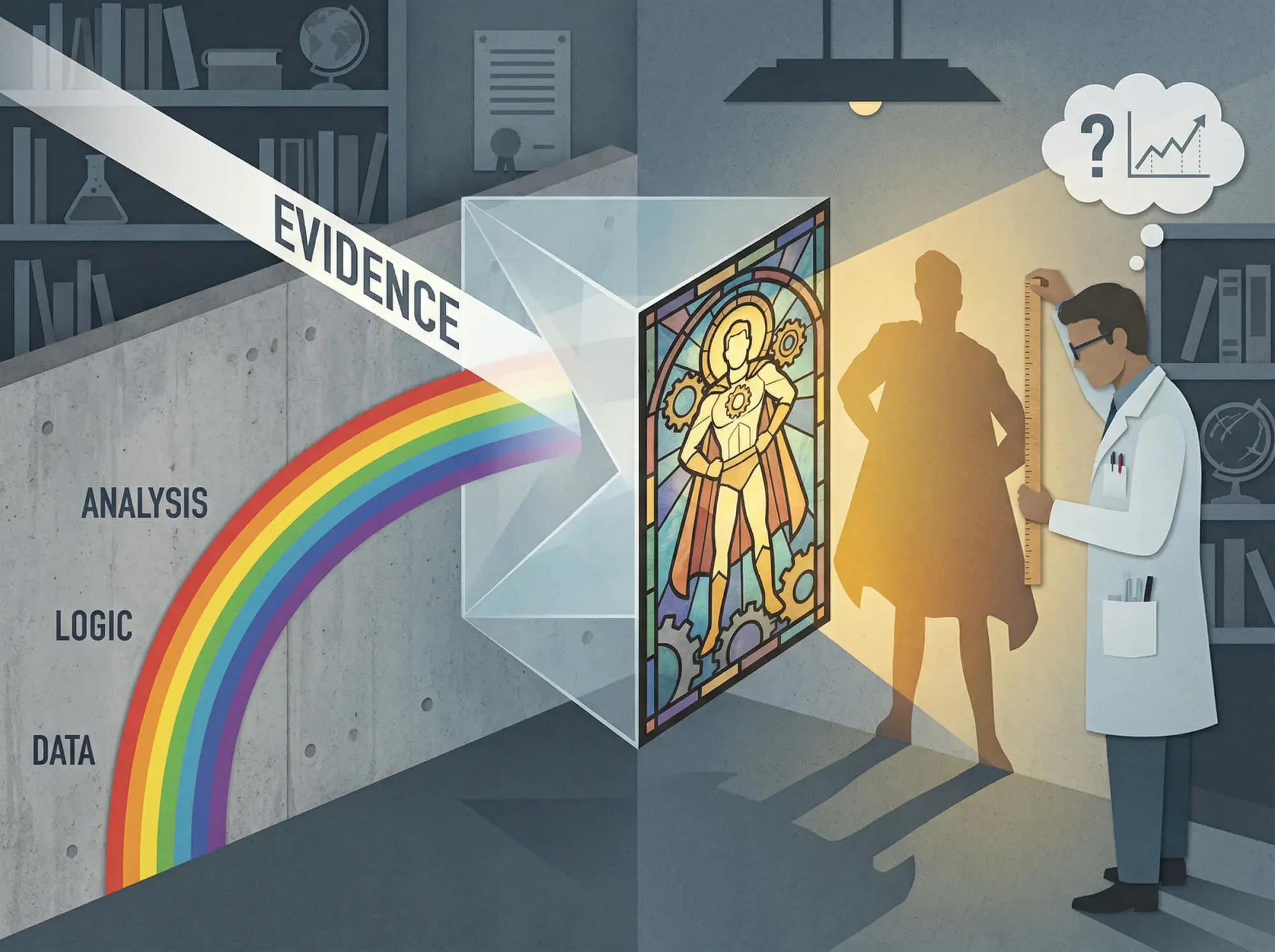

How Rational People Lower Standards of Reasoning When It Comes to Politicized Issues

One of the hardest things to accept, especially for people who care about rationality, is that epistemic rigor is rarely applied consistently. Most of us do not give up bad arguments. Instead, we give up standards of evidence when the conclusion becomes socially or morally important to us.

There are well-established psychological reasons why this happens. Decades of research in social psychology show that many of our beliefs are not just opinions we hold, but parts of who we are. They become woven into our identities, our friendships, and often our professional lives.

Put more simply, we build our identities, friendships, and careers around certain beliefs. As a result, challenges to those beliefs are not experienced as abstract disagreements but as personal threats. Our self-preservation mechanism kicks in: We bend reality as far as necessary to preserve a flattering story about ourselves and our ingroup. Denial and aggression toward the outgroup follow naturally.

Psychologists Henri Tajfel and John Turner, who developed Social Identity Theory, showed that people internalize the values and beliefs of the groups they belong to, treating them as extensions of the self. When those beliefs are questioned, the threat is processed much like a threat to your status or belonging. The reaction is often defensive rather than reflective.

More recent work on motivated reasoning helps explain why such a reaction is so persistent. In the 1990s, psychologist Ziva Kunda demonstrated that people selectively evaluate evidence in ways that protect conclusions they are already motivated to believe. When a belief supports your identity or social standing, the mind unconsciously applies stricter standards to disconfirming evidence and looser standards to supporting evidence.

Intelligence does not necessarily make you more objective; it can make you a more effective advocate for your own side.

Political scientist Dan Kahan later expanded this idea with what he called “identity-protective cognition.” His research showed that people with higher cognitive ability are often better, not worse, at rationalizing beliefs that align with their cultural or political identities. In other words, intelligence does not necessarily make you more objective; it can make you a more effective advocate for your own side!

This body of research helps explain why challenges to core beliefs can feel existential. If your moral worldview underwrites your relationships, your career, or your sense of being a good person, abandoning it comes with real social and psychological costs. Under those conditions, defending the belief feels like defending your life as it is currently organized.

Seen in this light, the selective abandonment of evidentiary standards is not a moral failing unique to any one group. It is a predictable human response to perceived identity threat. Reasoning shifts from a tool for understanding the world to a mechanism for self-preservation.

I learned this firsthand during my years in the New Atheist movement. What struck me was how selective people’s skepticism could be. In debates about religion, the standards were ruthless. In debates about politics and social issues, those same standards were easily relaxed, and often vanished.

Take prayer. For decades, skeptics have pointed to controlled trials showing no measurable benefit of intercessory prayer. The best-known example is the STEP trial, a randomized study of nearly 1,800 cardiac bypass patients published in The American Heart Journal. It found no improvement in outcomes for patients who were prayed for, and in one group outcomes were slightly worse among patients who knew they were being prayed for. Among the New Atheists, prayer was considered resolved beyond reasonable debate not only because the experimental evidence showed no effect, but because the underlying causal story itself collapsed upon examination.

Reasoning shifts from a tool for understanding the world to a mechanism for self-preservation.

Philosophically, intercessory prayer fails at the most basic level: It posits an immaterial agent intervening in the physical world in ways that are neither specified nor independently detectable. There is no plausible mechanism, no dose-response relationship, no way to distinguish divine intervention from coincidence, regression to the mean, or natural recovery.

When some studies do claim positive effects of prayer, they almost invariably collapse under close inspection—small sample sizes, multiple uncorrected comparisons, vague outcome measures, post hoc subgroup analyses, or outright publication bias. Some define “answered prayer” so flexibly that any outcome counts as success; others rely on self-reported well-being, which is especially vulnerable to expectancy effects and motivated reasoning.

This is precisely why large, preregistered trials and systematic reviews, such as those published in The American Heart Journal, are treated as decisive: They close off these escape hatches. The conclusion that prayer “doesn’t work” is not dogma; it is the residue left after methodological rigor strips away every alternative explanation.

Now compare that level of scrutiny to how many people treat evidence in politically favored domains. What matters here is not even whether these conclusions are right or wrong, but how they become insulated from refutation.

In debates over trans healthcare, for example, studies in favor of many invasive medical interventions are based largely on self-reported outcomes, short follow-up periods, and substantial attrition. Despite these limitations, they are frequently treated as definitive. Criticisms that would be routine in almost any other medical context are instead dismissed as bad faith. But the fact that these issues involve real suffering should not exempt them from evidentiary scrutiny; it should raise the bar for it. In this case, the most comprehensive evidence available—multiple systematic reviews—has raised serious concerns about the overall quality of the evidence base, particularly with respect to pediatric interventions.

The UK’s Cass Review, commissioned by the National Health Service and published in stages between 2022 and 2024, concluded that the evidence for puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones in adolescents is generally of low certainty. Similar conclusions were reached by Sweden’s National Board of Health and Welfare and Finland’s Council for Choices in Health Care, both of which revised clinical guidelines after finding the evidence weaker than previously assumed. None of this proves that such treatments never help anyone, especially adults who exhausted other options. It does show that claims of scientific certainty are unjustified.

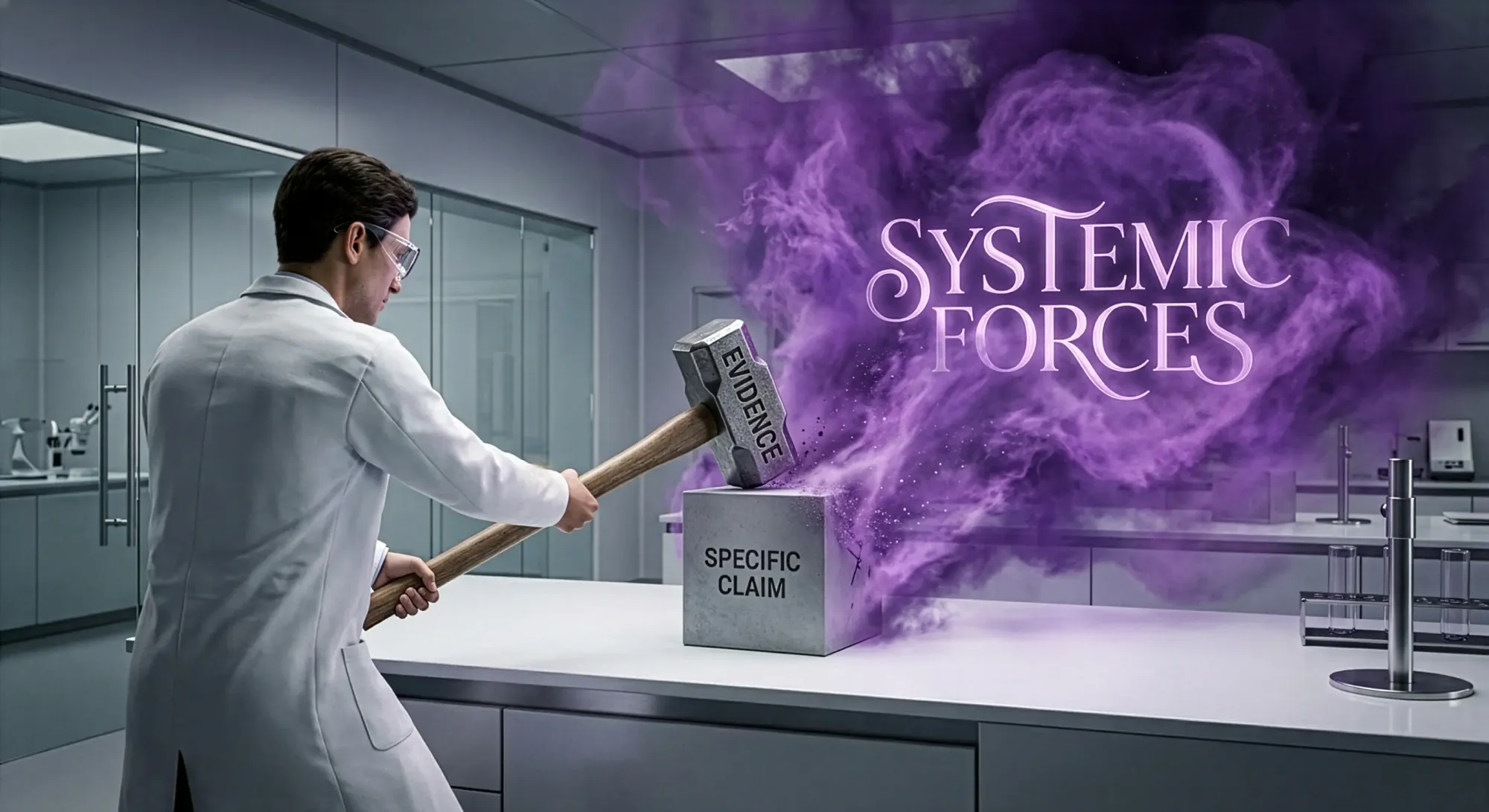

The same pattern appears at the level of theory. New Atheists made a cottage industry out of attacking unfalsifiable religious claims and god-of-the-gaps reasoning. Yet many of the same people now defend claims about “systemic discrimination” that are structured in exactly the same way: When disparities persist, they are treated as proof. When they shrink, the explanation retreats to subtler and less measurable mechanisms. Evidence against the claim rarely counts against the claim in the way it would in other domains.

Consider policing. It is often treated as a settled fact that racial bias is the primary driver of police shootings. But when Harvard economist Roland Fryer examined multiple large national datasets on police use of force, he found that there were no racial differences in officer-involved shootings once relevant contextual factors—such as crime rates, encounter circumstances, and suspect behavior—were taken into account.

What followed was not a broad reevaluation of the claim, but a shift in how it was framed. Rather than direct bias operating at the level of individual officers, explanations moved toward less specific and harder-to-measure forces: institutional culture, historical legacy, or diffuse forms of “structural” racism. These explanations may or may not be true, but they function differently from the original claim. Because they are more abstract and less tightly specified, they are also far more difficult to test or falsify.

Here’s the key issue: The pattern we can observe in all this is not that evidence resolved the question, but that disconfirming evidence changed the nature of the claim itself. A hypothesis that was once presented as empirically straightforward became broader, more elastic, and increasingly insulated from direct empirical challenge. Sounds familiar? It’s the god of the gaps fallacy.

The same pattern appears in debates over wage gaps. Raw differences in average earnings between groups are often presented as straightforward evidence of discrimination. But when researchers such as June O’Neill and later Claudia Goldin showed that simply controlling for factors such as occupation, hours worked, experience, career interruptions, and job risk substantially narrows or eliminates many commonly cited wage disparities, the original claim quietly shifted.

Evidence that would count against the claim in any other domain instead causes the claim to become broader, more abstract, and less falsifiable.

It was no longer argued that some demographics were being paid less than others for the same work under the same conditions. Instead, the explanation moved upstream: Sexism or systemic racism were said to operate on the variables themselves, shaping career choices, work hours, and occupational sorting in ways that produced lower average pay.

Again, these higher-level explanations may be partly true. But they function very differently from the initial claim. A hypothesis that began as a concrete, testable assertion about unequal pay for equal work became broader, more abstract, and harder to falsify. Evidence that would ordinarily count against the claim did not weaken it; it simply pushed the claim into less measurable territory. In other words, evidence that would count against the claim in any other domain instead causes the claim to become broader, more abstract, and less falsifiable. In these cases, disparities function the way miracles once did in theology: as proof of hidden forces.

What bothered me about the New Atheism movement was not disagreement over conclusions. It was the collapse of standards. Arguments once dismissed as unscientific were rehabilitated the moment they became morally fashionable. I focus here on the New Atheism movement because it marked the first time in my life (and, as far as I can tell, the first time in history) that a movement, at least on its surface, explicitly committed itself to applying the highest standards of evidence to some of the most consequential claims about the world, and in doing so successfully and very publicly dismantled societal structures and beliefs that had endured for millennia.

Skepticism is adopted when it flatters the self and abandoned when it threatens a moral narrative.

I’ve been thinking about all this for a long time, and I’ve come to suspect that most people—not by choice, but by evolutionary design—do not want or need a fully accurate understanding of how the world works. They want beliefs that protect their identity, signal membership in the right group, and increase their chances of (social) survival. Michael Shermer explained some of the evolutionary processes at hand here rather well in his books How We Believe and Conspiracy. In short, when it comes to patternicity—the human tendency to find meaningful patterns in meaningless noise—making Type 1 errors, (i.e., finding nonexistent patterns), carries little evolutionary risk while the opposite (i.e., missing real patterns) often can be the difference between life and death. This means that natural selection will favor strategies that make many incorrect causal associations in order to establish those that are essential for survival and reproduction.

Under those conditions, reasoning becomes performative. Skepticism is adopted when it flatters the self and abandoned when it threatens a moral narrative. That is why debates on these topics so often drift toward unfalsifiable language and moral imperatives.

A fair question follows: How does anyone know they are not doing the same thing?

I think the real danger we should try to internalize is not that other people do this. It is that all of us do.