Can We Still Trust the Experts? The Siren Song of Influence

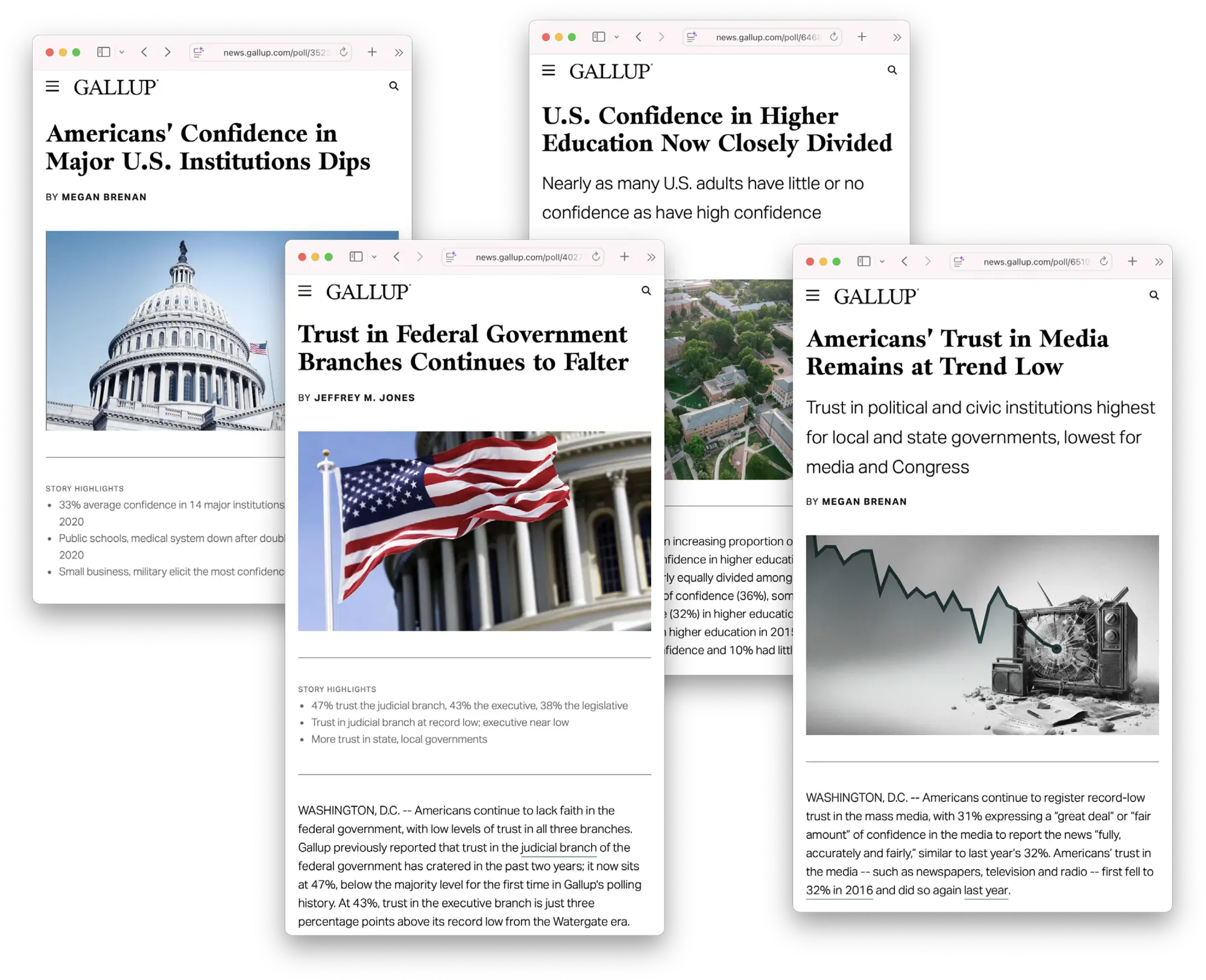

The phrase “trust the science,” once an epistemic humble appeal to evidence, has in recent years morphed into an imperious demand. As trust in institutions, including scientific ones, continues to spiral downward,1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 many academics and scientific organizations seem to believe the solution lies in louder messaging, greater moral certainty, progressive political activism, and the routine denigration of “science deniers” (or, worse, pseudoscientists!). These efforts now saturate social media feeds, blog posts, and podcasts, often delivered with the exasperated insistence that the masses must, above all, trust in science.

It isn’t working.

Science earned its authority not by telling people what to believe or how to live, but by serving the public in offering high-quality information that helps people solve problems and achieve their goals. But in the age of social media, a growing number of scientists appear less interested in the patient work of discovery and more interested in being political influencers. They post partisan hot takes, endorse candidates, and signal ideological commitments, often leveraging their authority as scientists to advance personal or political aims. This doesn’t just alienate half the country (usually the right-leaning half); it undermines the hard-won and always precarious reputation of science as a dispassionate arbiter of truth. The more we scientists insert ourselves into political battles, the more we risk losing the very authority we seek to protect.

Trust Is Earned, Not Demanded

Trust doesn’t come from demands for deference. It comes from repeated demonstrations of competence. It’s earned by delivering results. Evolutionary scholars have documented status conferral across cultures, showing that generating benefits for others is the primary path to earning prestige and influence.12, 13 Status gained through dominance or coercion can work in the short term, but it breeds resentment and unstable hierarchies, not durable trust.

Humans are deeply attuned to and wary of attempts to seize power, especially when those attempts feel illegitimate.14 Even political leaders, whose roles require a public pursuit of power, must tread carefully. As Smith and colleagues observed:

People accept and revere leaders who are believed to be sacrificing for the welfare of the group, who clearly desire no personal benefits from their leadership, or, better yet, did not desire leadership in the first place … Strong, modest, reticent leaders are looked up to because of their actions and because such leaders lack political ambition.15

Assuming the film Conclave generally captures the reality of how popes are chosen, similar social forces apply to winning the papacy too. Chi entra papa in conclave, ne esce cardinale—“Whoever enters a conclave as pope, exits a cardinal.” Transparent campaigning or politicking are likelier to decrease rather than increase chances of becoming Pope.16

Smith and colleagues go on to suggest that one reason politicians are so widely despised is that they must openly declare their desire for power. Politicians may hold influence, but they are also among the least trusted and most intensely disliked individuals in public life. Visible attempts at power invite skepticism and contempt.

The Lucky Lot of Scientists

Unlike politicians, scientists aren’t required to declare their ambition (even though many may privately harbor it). Indeed, scientists are almost uniquely positioned to earn prestige in society without appearing power-hungry. The scientific method, though imperfect, is specifically designed to minimize biases, flawed analyses, and imprecise claims. Thanks to peer review, growing transparency norms, and a culture of empirical accountability, science is the best system for arriving at truths (at least for now).

So long as scholars stick to their core mission—identifying and describing empirical reality—they can offer something genuinely useful to the world. Scientific insights provide the foundation for every modern advancement: better technology, lifesaving medicine, more effective institutions, and all manner of life hacks that help individuals pursue lives aligned with their values.

In the age of social media, a growing number of scientists appear less interested in the patient work of discovery and more interested in being political influencers.

Science has something helpful to offer. And helpfulness leads to status and influence.

Of course, discovering genuinely new and useful information is hard. It can take years of uncertain and tedious work. And in some disciplines, the well of discovery may be running dry. Firing off a polarizing tweet, by contrast, might take just a few minutes and still deliver thousands of likes, hundreds of new followers, and a fleeting but real sense of importance.

The Seduction of Influence

The job of an academic used to be much quieter. Scholars were known to their students, immediate colleagues, and those in their broader subdiscipline, but few scholars reached public awareness, and when they did—as in the examples of Carl Sagan and Stephen Jay Gould, who rose to public intellectual stardom—were punished by colleagues and accused of sacrificing scholarship for “popularization.”17, 18 Now, with podcasts, blogs, and especially social media, scholars frequently speak directly to the public, amassing followers, attention, and influence. This shift allows scholars who have relevant expertise to share knowledge about pressing societal issues. However, this attention marketplace also distorts academic incentives. Likes, retweets, and follows reward attention-grabbing content rather than careful analysis.

Ideally, science rewards rigorous, methodical work, a system that is constraining and at times, painfully slow. The influencer economy operates on precisely the opposite logic. It rewards negative, emotional, divisive content.19, 20 It moves fast, so rewards are delivered more quickly, making it even more alluring. A viral tweet can return more validation in twelve hours than a peer-reviewed paper offers in two years. And the more you post—and the more emotionally charged the language used in the post—the greater your chances of going viral. Quantity trumps quality, since each tweet, however meagre, is one more shot to win 𝕏 (Twitter) for the day.

Earlier generations of scholars earned prestige over decades through meaningful contributions to their fields. A rare few reached broader public fame. Today, a scholar with little expertise but strong opinions and a fiery temperament can swiftly reach “public intellectual” status. It doesn’t take much experience with social media to learn that the currency of influence is provocation, not precision, and that fanning the flames of controversy drives engagement.

In playing the role of partisan thought leaders, scientists increasingly engage in behaviors that may boost their online stature and serve their ideological causes, while undermining public trust in scientists generally.

Such quick-won influence is seductive. It allows scholars to build personal brands, shape public opinion, and rise to hero status in their ideological tribes. The temptation to wrap one’s political beliefs in the authority of “science” is hard to resist.

However, in playing the role of partisan thought leaders, scientists increasingly engage in behaviors that may boost their online stature and serve their ideological causes, while undermining public trust in scientists generally. A recent study found that scientists who post more political content on 𝕏 are seen as less credible than politically neutral scientists.21 This same study also found that scientists were aware of the reputational costs of posting political opinions on social media, yet in a sample of nearly 98,000 academics on X, roughly half chose to do so despite potential damage to their status.

A smaller but still substantial subset of academics go further, using their platforms to insult or belittle perceived political enemies: Christians, Republicans, Trump voters, conservatives, White people, men, rich people, old people, straight people, cisgender people, Jewish people, ruralites, and anyone who defends any of the above. (Since academics lean far to the political left, the above targets are the most popular, but some on the right post to “own the libs,” denigrate the “libtards,” and generally despair the “blue-haired, nose-ringed, tattooed, screaming progressives.”) Meanwhile, labeling someone “sexist” no longer requires treating women worse than men. It might mean treating them equally (anti-affirmative action sexism) or even treating them better (benevolent sexism). Add it all up, and the list of people implicitly or explicitly treated as backward bigots by the academic elite likely includes a large majority of the population. It should not be surprising, then, that many of those accused of bigotry are skeptical of scholars who publicly mock their identities, values, or way of life.

Sometimes, the problem is not mockery but overconfidence. Driven by fear that the public might behave selfishly or irrationally if given too much nuance, some scientists bend the truth—delivering simplified, confident messages that sound authoritative but overstate the evidence. This was especially visible during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public health advice was often communicated as based on authoritative fact, only to be overturned, revised, and then reversed again. Scientists cannot be blamed for not having all the answers in the face of a novel virus. They can, however, be blamed for pretending they did and for failing to acknowledge previous errors when their advice changed. Instead of humility, the public was often met with new denunciations, new taboos, and new claims of scientific certainty.

A forthcoming paper by Graso and colleagues explore this dynamic directly.22 They found that scientific communicators who embraced accountability—by inviting discussion of dissenting views, acknowledging uncertainty, and taking responsibility for previous errors—elicited more trust and engagement than those who adopted authoritarian messaging, dismissed dissent, or labeled critics as “anti-science.” Despite concerns that the public must be controlled with simple, clear, and confident messaging, it may be that “honesty is the best policy” for maintaining long-term public trust in, and thus deference to, science.

Political activism in academia not only makes us look bad, it undermines the very thing we claim to offer: impartial, high-quality information.

Of course, individual scientists are free to denounce what they view as backwards or regressive ideas. However, this creates a collective action problem. Individual scholars may benefit from posting provocative, politically charged content. Yet as more scientists behave like partisan activists, public trust in the broader institution of science declines.

Politicization of Scientific Institutions

The damage is likely greater still when scientific institutions become politicized. This includes universities, scientific journals and their publishers, and academic professional societies. When these institutions act like political activists, it signals that politicization isn’t limited to a few rogue academics. It suggests broad, institutional-level buy-in from the scholarly community.

Research across management, psychology, and political science finds that when organizations and institutions “take sides” in ongoing political conflicts, the reputational consequences are almost uniformly negative.23, 24, 25, 26, 27 The costs of politicization are so well-documented that scholars often treat it as a threat imposed on science, something weaponized by politicians and special interest groups to discredit inconvenient findings.28, 29 It is puzzling, then, that scientific institutions have so eagerly politicized themselves and continue to do so.

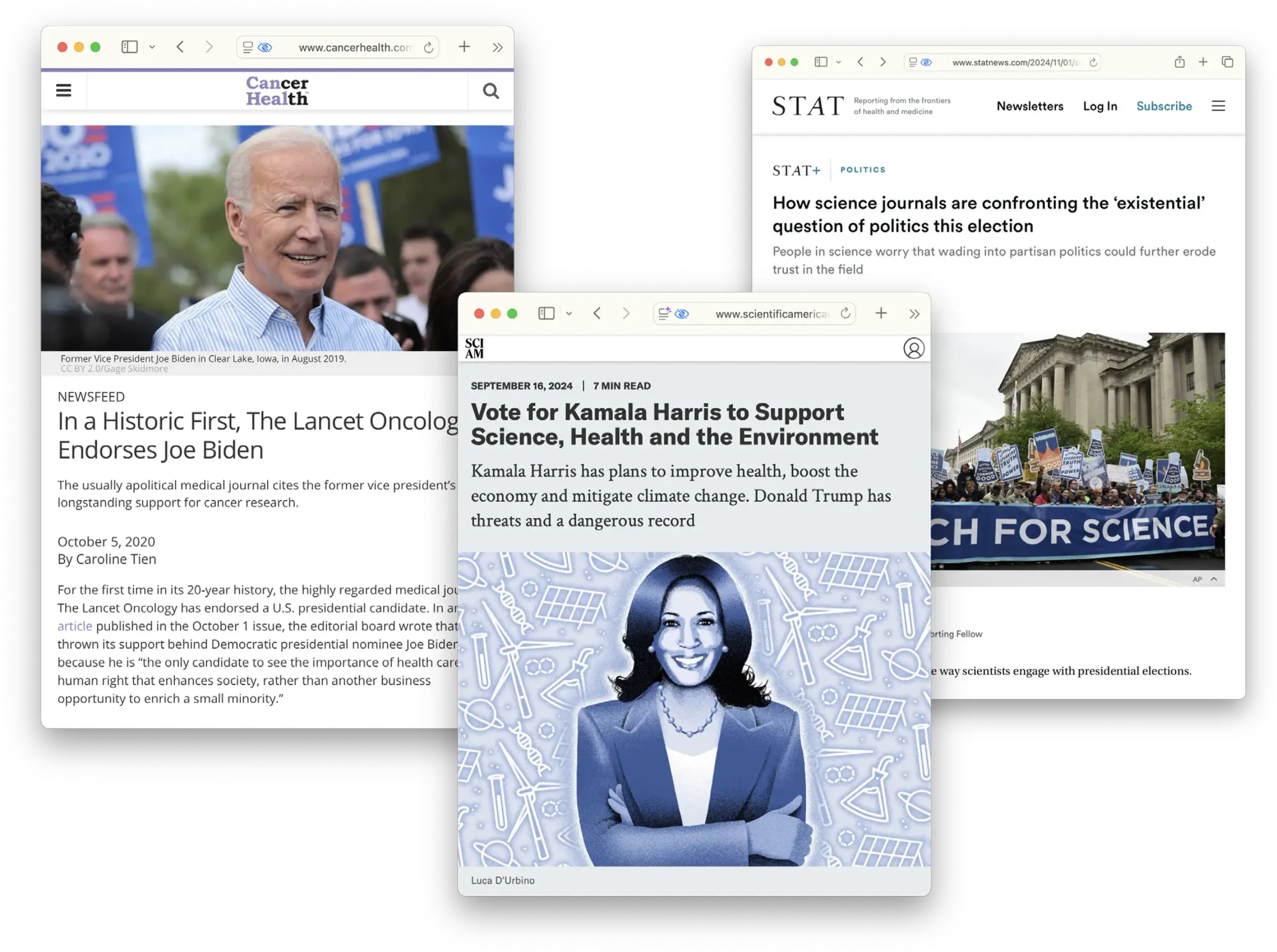

Some of the most striking examples of institutional politicization come from impactful academic and academic-adjacent journals such as Nature, Scientific American, and The Lancet, all of which have issued political candidate endorsements in recent years. If these were obscure or mid-tier journals, the reputational effects might be limited. However, these are among the most prestigious scientific publications in the world, so when they engage in political activism, people notice. And people don’t like it.

In a compelling demonstration of the public’s aversion to such endorsements, a recent study by Floyd Zhang randomly assigned a subset of participants to read about Nature’s endorsement of Joe Biden.30Among Trump supporters, exposure to this endorsement reduced trust in Nature’s informedness and impartiality and made them less likely to read articles in Nature. Any positive effects among Biden supporters were smaller and inconsistent. The Biden endorsement also reduced Trump supporters’ trust in U.S. scientists more broadly, while having little effect on Biden supporters. The endorsement also had virtually no influence on participants’ attitudes toward Trump or Biden. In other words, the endorsement was unlikely to have swayed any votes, but quite likely damaged trust in Nature, and potentially in the scientific community more broadly. Virtue signaling at its counterproductive worst?

Just as individual scientists use social media to advertise their political graces, so do scientific institutions. Springer Nature, for example, changed its 𝕏 logo to the Progress Pride flag. These public political displays, though certainly within the rights of a private organization, likely erode perceptions of the impartiality of scientific institutions, and thus the scientists within them.

Scientific institutions … should not endorse political candidates or take sides in ongoing political controversies.

One of us has examined how perceptions of politicization shape public trust, support, and willingness to defer to the expertise of various scientific disciplines and academic professional organizations.31 At the disciplinary level, we find strong associations between the perception that professors allow political values to influence their work and perceptions of (1) how trustworthy the discipline is, and (2) how skeptical students should be about what professors in that field teach. The disciplines perceived as least politicized (including math, physics, chemistry, English, nursing, and computer science) are also the most trusted and provoke the least skepticism. In contrast, disciplines viewed as highly politicized (including religious studies, gender studies, ethnic studies, and political science [perhaps an unfortunate name choice]) tend to be the least trusted and elicit the most skepticism.

Although these patterns are somewhat stronger among political outgroup members (typically conservatives), the relationships are nearly always negative across the political spectrum. Even left-leaning members of the public express lower trust and greater skepticism toward disciplines they perceive as allowing political values—including left-leaning values—to influence their work.

In follow-up studies, we tested the causal effects of politicization on trust and related outcomes. In one experiment, participants read about a fictional society of economists and its recent conference. In the control condition, participants simply learned about the organization’s standard activities. In the politicized conditions, the society had invited either a Democratic or Republican governor to deliver the keynote address, advocating for policies aligned with their respective parties.

In both politicized conditions, participants reported lower trust and greater skepticism toward the society itself and toward economists more generally. These declines were largest among political outgroup members (e.g., conservatives responding to a Democratic speaker), but trust dropped even among ingroup members. That is, compared to the control group, conservatives reported lower trust even when the speaker was a Republican, and liberals reported lower trust even when the speaker was a Democrat.

We found similar results in a later study involving a fictional public health professional society that engaged in political advocacy on social media. Whether advocating for left-leaning or right-leaning causes, trust and willingness to defer to the organization’s expertise declined (compared to a control condition). Although there were small positive effects among ideologically extreme ingroup participants, these were outweighed by much larger negative reactions among outgroup members, resulting in a net reputational cost. These costs extended to virtually all evaluations of the professional society. Participants exposed to the political tweets viewed the society as:

- likelier to harm public health,

- contributing to division and conflict,

- abusing their power,

- more biased,

- more dishonest,

- more selfish,

- and more in violation of their own personal values.

Together, these findings suggest that when academic disciplines or professional societies engage in visible political activism, the public reacts strongly and negatively. Moreover, these reputational costs are not limited to the specific organizations involved. Perceived politicization can erode trust in entire disciplines and professional communities.

Warnings Not Heeded

For at least 30 years, scholars have warned that progressive activism was spreading through academia and potentially distorting scholarly priorities, publishing standards, and even empirical results.32, 33This concern reached crescendo in the early 2010s after Jonathan Haidt delivered a timely and compelling speech about political bias in social psychology, pointing out that in a room of thousands of scholars, there were few if any Republicans, and that this almost certainly was damaging scholarship. Since then, scholars have contended that ideological homogeneity and the subsequent politicization of science was undermining the integrity of science,34 contributing to the replication crisis,35 proscribing topics at odds with a progressive agenda,36 elevating other dubious ideas aligned with the progressive worldview,37 causing discrimination against conservatives,38 leading to a hostile atmosphere that violates the free speech rights of some and intimidates many others into self-censorship,39, 40 while corroding trust in the institution of science.41

Political activism in academia not only makes us look bad, it undermines the very thing we claim to offer: impartial, high-quality information. Social media amplified the problem, laying bare the extremism and hostility that were once confined to internal conversations. If the scientific community previously enjoyed at least a patina of neutrality, that sheen has largely worn off. Academia long infused scientific work with political values, largely without consequence. Now, thanks in part to highly visible activist behavior by scholars and institutions, we are paying the proverbial piper.

The solution lies in a collective recommitment to the core values of science and a scaling back of everything else.

It is unfortunate but unsurprising that the political right now wants to punish academia and often delights in the hostile rhetoric and acts taken by the Trump administration against elite universities across the United States. One need not endorse these efforts nor encourage belligerent anti-academic rhetoric to acknowledge that academia bears some responsibility for its deteriorating reputation among conservatives and its declining authority with the broader public.

We cannot control public opinion, nor can we dictate the actions of elected officials. However, we do have control over our own behavior. If we are serious about regaining credibility, then we must begin by holding ourselves accountable. (If every person in your department votes Democrat and you don’t know a single person who votes Republican, you’re in a political bubble and stand next to no chance of being politically neutral and objective when it comes to studying social and political issues, and your students are not going to get an impartial education.)

The Path Toward Credibility

Academia often responds to problems by engaging in bureaucratic bloat. In this case, however, credibility cannot be restored through creating more committees or issuing new strategic plans. Instead, the solution lies in a collective recommitment to the core values of science and a scaling backof everything else.

Scientific institutions (departments, universities, publishers, journals, professional societies) should not endorse political candidates or take sides in ongoing political controversies. They should resist the temptation to post ideological content on social media or use official platforms to signal tribal allegiance. Institutions should recommit to merit, and eliminate programs and priorities that elevate other divisive moral and political values (think DEI). When leadership elections arise, we should choose scholars committed to scientific integrity, not political activism.

Individual scientists should also rethink their public engagement. Building a brand around partisan identity or expressing open hostility toward large swaths of the population might attract attention, but it does not improve scholarly credibility. Neither does issuing sweeping “consensus statements” on unresolved social issues. Where true consensuses exist, there is no need for such statements. Instead of overstating certainty, scientists should model epistemic humility, acknowledging uncertainty where it exists, and being transparent about the limitations of our knowledge. Given the long history of scientists getting things wrong, scientific findings should be communicated tentatively, not as “proven” facts. And scholars should resist the urge to demand, “Trust the science!” The moment such a command is felt necessary is usually the moment there is no single, settled science to trust.

Science is not a body of dogmas to be trusted or deferred to. Rather, it is a process that is always provisional and whose primary virtue is precisely that it disdains all authority save that of the rational mind.

♦ ♦ ♦

Scientists are human. And like other humans, they desire fame and power and often choose the quickest route to obtain them. This is why scientific institutions are necessary. They restrain the worst excesses of each scientist, and like a free market, they often use the fuel of individual ambition to power an engine of knowledge that benefits everybody.

When scientific institutions are degraded by political bias, when they no longer check individual desires for status or influence, science as an institution suffers. It degenerates into a tool for individual advancement and a bludgeon to smite political foes. As consequence, people become skeptical not just of this or that theory, this or that paper, but of its entire claim to be the pursuit of objective truth. As a result, they come to view the university not as vital part of the culture but as a hostile, politically motivated bully.

It is tempting to anoint oneself with the authority and credibility of science so as to assume the status of moral and political authorities. If, however, we want science to continue to have that authority, we must return to the slow, unglamorous, often tedious process that made the findings of science worthy of credibility in the first place.