A Skeptic’s Guide to Immigration

In 1965, the 33-year-old junior Senator from Massachusetts, Edward “Ted” Kennedy, took the floor to deliver his remarks on a bill that promised the American people little change:

The bill will not flood our cities with immigrants. It will not upset the ethnic mix of our society. It will not relax the standards of admission. It will not cause American workers to lose their jobs.1

This statement—unimaginable from any Democrat today—summarized both Kennedy’s own thinking and his party’s main argument in support of the most liberal immigration bill ever enacted in the history of the world—the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act. It was passed by a New Deal congress and signed into law by a New Deal president whose positions on union organization, healthcare, antitrust, and virtually every other economic issue are to the left of today’s Democratic Party, but whose opinions on immigration would be considered right wing and racist by modern progressive standards.2

What President Johnson proclaimed as “not a revolutionary bill”3 on the day of its signing, over the coming decades completely transformed this country’s demographic fabric, economic identity, and cultural psyche in ways that neither Kennedy, Johnson, nor those opposed to the 1965 bill foresaw. The American immigration system they created remains fundamentally unchanged and is unlike any other in both design and consequence. Distinct from most other developed nations that prioritize skilled workers and use points-based systems to meet labor market demands, (i.e., the more skilled and well-educated the prospective immigrant, and the higher their job offer is, the more likely they are to be admitted) the United States emphasizes family reunification, granting two-thirds of green cards to relatives of citizens or permanent residents. It also offers birthright citizenship, a policy shared by only a handful of countries, and a Diversity Visa Lottery that annually grants permanent residency to 55,000 randomly selected immigrants from underrepresented nations—programs that would be unthinkable in most European systems.4 The H-1B visa program, intended to bring in foreign workers for specialty occupations, also operates as a lottery system rather than the more common points-based system favored by other countries. This means that even if an employer wants to hire a specific, highly skilled worker, that candidate can only be hired if they win an annual lottery—competing against all other applicants in the same visa category. Their chances aren’t high—the number of H-1B visas granted is limited by a congressionally mandated annual cap of just 65,000. In 2024, the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services received 758,994 H-1B visa applications. The sheer scale of the U.S. system—with desired quotas that exceed those of every other nation5, 6, 7—also sets it apart, making it the most expansive and complex immigration system in existence.

The United States is currently home to one fifth of the world’s immigrant population.8 It draws people from virtually every country on Earth,9 recording over a million10 legal entries and estimating close to two and a half million illegal entries every year.11 This unprecedented influx has warped the national conversation into one that also fails to find a precedent. Never before has immigration polled as both the most important and polarizing political issue,12 often framing itself as binary, with individuals and politicians declaring themselves as either pro- or anti-immigration. Historically, the debate has centered around more nuanced questions of who, how many, and under what conditions.

The Battle Over Borders

In America today, the single greatest divide between Democrats and Republicans is education. In the most recent election, Donald Trump won the White non-college educated vote two to one.13 This matters because the same moral frameworks that divide college and non-college educated Americans also drive views on immigration.

Psychologists have identified five core human values: care, fairness, sanctity, authority, and loyalty. Across the globe, college-educated professionals consistently rank two of these above the rest—care for others, especially the vulnerable, and fairness—placing them at the heart of their worldview and moral calculus. While working-class individuals also prioritize care and fairness, these values don’t dominate their framework in the same way. Instead, they are weighted alongside values that matter little to the educated class—appreciation of tradition, respect for authority, and loyalty to family and community.14 It is a divide many researchers have described as the split between “universalists” and “communalists.”

At its core, today’s immigration debate is a microcosm of the broader conflict between universalist and communalist ideals. For communalists, a country should restrict entry and prioritize its own people. For universalists, patriotic loyalties are dangerous and immigration is seen as a solution for closing the gap between rich and poor nations. Polls indicate that liberals tend to be universalists who support more open-door policies while conservatives tend to be communalists who favor policies that limit the number of immigrant arrivals.15

The United States is currently home to one fifth of the world’s immigrant population.

In the past, however, the immigration debate has not split so neatly across these lines. For most of American history, communalist views were not tied to conservatism. Indeed many 20th century communalists were progressives who rooted ideas of fairness and equality in the local or national community rather than seeing the issues as global causes. A. Philip Randolph—perhaps second to only Martin Luther King Jr., as America’s most prominent Black civil rights leader—for example, called for:

a halt on the grand rush for American gold, which overfloods the labor market, resulting in lowering the standard of living, race riots, and general social degradation. The excessive immigration is against the interests of the masses of all races and nationalities in the country—both foreign and native.16

The conservative intellectual giant and universalist Milton Friedman, meanwhile, positioned himself firmly on the other side of the debate as a strong advocate for higher levels of immigration.17

Since 1965, however, the views of both conservatives and liberals have converged on a pro-immigration platform. The Democrats transformed themselves into a college-educated party of social and cultural elites whose universalist worldview prioritizes human rights over American rights, while at the same time Republicans remained loyal to big business and free-market philosophies that also see benefits in a higher share of immigrant labor. According to an analysis of the Congressional Record, Democrats now speak more positively about immigration than any party has at any time in our nation’s history.18 And until Trump’s takeover of the Republican party in 2016, the right by and large agreed. It was, after all, President George W. Bush who tried to pass a bill establishing an easier pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants.19

My own research on immigration suggests that much of the backlash to decades of record-breaking immigration with little pushback from politicians in either party resulted in the surge of populist candidates on both the right with Donald Trump and on the left with Bernie Sanders.20 During the 2016 presidential campaign, both Trump and Sanders broke with their parties on the issue of immigration, with Bernie in 2015 criticizing open border policies as “right-wing proposal[s]” that “[make] people in this country more poor than they already are,”21 and Trump infamously stating that “they [illegal immigrants] are bringing drugs, they’re bringing crime” in his presidential announcement speech.22

A decade later, in 2025, Donald Trump’s first bill signed as president was the Laken Riley Act, making it the first piece of legislation passed on the issue of immigration in over 20 years.23 Republican backers of the new legislation hope it is the first in a series of laws that remake our immigration system for the first time since 1965. Trump has already signed executive orders to end birthright citizenship, expand expedited removals, and ban asylum claims as part of his “deport them all” agenda.24 Meanwhile, Democrats appear to have hired John Lennon as their chief immigration strategist, drafting policy straight from the lyrics of Imagine, where “there’s no countries” and with “all the people sharing all the world.” During the 2020 Democratic primary, Cory Booker promised to “virtually eliminate immigration detention” and fellow candidate Julian Castro unveiled a proposal to decriminalize illegal immigration and eliminate the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.25 Admittedly, Democrats have recently been forced by public opinion to back off many of these proposals, yet they remain unable to offer a coherent immigration policy beyond vague rhetoric. Who knows how this will all shake out, but here are some things that should be considered:

Economic Impact of Immigration

There are over 100,000 peer-reviewed articles on immigration. Its inconsistent effects, unintended costs, and contradictory benefits make it one of the most complex topics for social scientists and policy makers to understand. If you are looking for an answer as to whether immigration is good or bad, stop reading now. This is not to say that there are no answers or that nothing is known, but what it does mean is that what follows is unlikely to satisfy any one side of the political debate or provide a definitive blueprint for how to fix our broken system.

A fragile consensus has emerged that high-skilled workers—no matter their defects—tend to pay off and outperform their low-skilled counterparts.

The economic effects of immigration are as varied as the immigrants themselves. Research suggests that immigrants who speak better English,26, 27, 28 stay married longer,29 are more willing to relocate within the U.S.,30 and who have less immediate family in the countries from which they came,31, 32 contribute more and cost less. Conversely, those who are excessively obese,33 choose to settle in rural neighborhoods,34 are worse at making friends,35 and who avoid paying taxes36 contribute less and cost more. Most immigrants, however, straddle both sides of the ledger—offering a mix of strengths and liabilities, shaped by personal choices, circumstances, and the unpredictable forces of culture, policy, and industry change. Their economic impact is a tangle of self-interest, structural incentives, and social contingencies, producing outcomes that are neither fixed nor inevitable. Still, a fragile consensus has emerged that high-skilled workers—no matter their defects—tend to pay off and outperform their low-skilled counterparts. Reality, however, often disagrees.

Nowhere are these disagreements and the nuance of this issue clearer than when looking at the outcomes of immigrants across countries of origin. The high-skilled advantage appears ironclad when comparing Indians—the best educated (75 percent college graduates) and wealthiest ($72,000 median income) of all immigrant groups—to their next-door neighbors from Myanmar, who enter the United States as one of the least educated (23 percent college graduates) and, predictably, earn the least money among all Asian immigrants once here ($26,000 median income).37 Less predictable, however, are the economic gains of Mongolians, who are the third best educated among Asians (63 percent college graduates), yet make only slightly more than those from Myanmar ($28,000 median income) and suffer the highest rate of poverty across all Asian immigrant groups. Part of the explanation is that Mongolian immigrants’ rate of married-couple households ranks near the bottom of the Asian distribution—over a full standard deviation and a half below that of immigrants from both Myanmar and India—and second to last (only ahead of China) when it comes to English proficiency among the cohort of most educated Asian countries.38

A similar dynamic is observed when comparing39 sub-Saharan Africans to Caribbean-born Blacks, where the relationship between education (i.e., high-skilled) and money also appears elusive. Although sub-Saharan Africans are among the most educated immigrants in the country, they report some of the lowest incomes and rates of homeownership. Black immigrants from the Caribbean, meanwhile, arrive as one of the least educated groups, but end up with higher incomes and higher rates of homeownership. Disparities like these complicate efforts to predict who will do best and remind us that success is not simply a product of technical expertise, but is deeply influenced by forces such as upbringing, cultural adaptability, social capital, and other variables that are far more difficult to measure.

One easy-to-measure metric, however, is age. Younger-aged immigrants almost always contribute more to the U.S. economy than older ones, regardless of skill level. One study40 showed that immigrants aged 18–24 without a bachelor’s degree generate a net-fiscal impact more than twice as large as that of immigrants over 44 with a bachelor’s degree. This effect is exaggerated when looking at college graduates over the age of 54, whose net contribution is even less than those who never graduated from high school but who arrived younger than 35.

Even so, the distinction between low-skilled and high-skilled immigrants remains the most salient for most researchers. It offers a clear binary—one rooted in decades of research—and illuminates broader trends, even if it fails to capture certain key nuances or industry-specific dynamics. The first important fact in this debate, however, is that low-skilled immigrants greatly outnumber high-skilled ones. Around two-thirds of all immigrants (legal and illegal) to the United States qualify as low skilled—seventy percent of whom do not even have a high school diploma41—and a handful of broadly generalizable characteristics help explain why they tend to be worse for the economy than their higher skilled counterparts.

For starters, the vast majority of illegal entries into this country are unskilled laborers.42 This means that they avoid any third-party selection process or policy oversight that allows the U.S. government to decide which immigrant category groups are needed where, and to strategize the best ways to integrate them into the economy. Strategies that might include spreading their share of labor across greater geographic distances to avoid oversupplying markets or simply mandating them to learn English. Low-skilled immigrants are also more likely to rely on social welfare,43 contribute less in taxes,44 compete more for jobs in unionized industries where they undermine collective bargaining agreements,45 and exhibit overall lower rates of upward mobility.46 High-skilled immigrants aren’t always “better”—but they usually are. Exactly by how much, however, is where the research becomes less clear and defies easy quantification.

Some studies suggest that low-skilled immigrants significantly suppress wages, others suggest only marginal effects, and a few strain to make the case that there are virtually no negative economic impacts linked to importing low-skilled labor whatsoever. The usual suspect in this last category is a 1990 paper published by Berkeley economist David Card.47

Card’s study48 sought to determine the effect of mass immigration on native wages by analyzing the Mariel Boatlift—a sanctioned exodus of mostly low-skilled workers from Cuba by Fidel Castro in 1980, which rapidly increased Miami’s labor force by more than 125,000. Comparing Miami to cities without an immigration surge, his analysis found no significant impact on wages for native-born workers, even among those without a high school diploma. Although wages in Miami fell overall, he found that they did not drop any more for those he regarded as competing with the Cuban arrivals than for those who weren’t. His conclusion ran counter to decades of previous research, but was substantiated by subsequent quasi natural experiments in Israel49 and Denmark,50 which similarly failed to find major wage suppression caused by immigration. The prevailing explanation for these counterintuitive results is that immigrants contribute to both the supply and demand for labor. That is, while they compete for jobs, they also create higher demand for goods and services, fueling employment, and thereby mitigating the expected downward pressure on wages. Card’s proponents also argue that the long-term gains from immigration—such as increased entrepreneurship and labor specialization—are rarely captured by most analyses, while the immediate fiscal costs, particularly at the local level, exacerbate public perceptions of harm.51

But Card’s work is not without its critics. In 2015, Harvard economist George Borjas reanalyzed52 the Mariel Boatlift, finding unreported, important results obscured by averages in the original work. He, for example, found that high school dropouts experienced a 30 percent wage decline—an outcome he attributed to direct competition between low-skilled immigrants and similarly skilled native workers. While his findings were scrutinized for methodological issues, including a small sample size and selective exclusions, they highlight how aggregate effects often obscure the uneven distribution of impacts across different groups. Research by the Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford53 and others,54, 55 lend further support to the more common-sense intuition that low-skilled immigration tends to depress wages and reduce job opportunities, particularly in the short term, before labor markets have time to adjust. Not to mention Card’s own findings in subsequent research,56 which predicts that, “an inflow rate of 10 percent for one occupation group would reduce relative wages for [that] occupation by 1.5 percent” and result in “a 0.5-percentage-point reduction in the employment rate of the group.” This same model projects a 3 percent wage loss when the immigrant inflow rate increases to 20 percent.

These numbers, however, are among the more conservative estimates when compared with those published by the National Academy of Sciences57 in a comprehensive 600-plus-page report produced by a committee that included both Borjas and Card. According to their summary, immigration exerts a small to moderate effect on wages, varying based on factors like regional labor supply, industry composition, and macroeconomic conditions—but never in the positive direction.*

The left’s claim that immigration doesn’t depress wages mirrors the same kind of speculative ideological optimism that Republicans engage in when discussing trickle-down economics and the Laffer curve. For neither group is the question empirical, and for both the flawed logic is evident even without complex data analysis.

Immigration wasn’t just a source of cheap labor for industrial barons—it was a strategic tool to divide, weaken, and conquer the working class.

In 2007,58 a local chicken-processing company in Stillmore, Georgia, lost 75 percent of its workforce in a single weekend after a raid by federal immigration agents. Within days, the company put up an ad in the local newspaper announcing jobs at higher wages. It’s basic economics. When the supply of a good increases, the price of that good falls. When that good is labor, the cheaper price means a cheaper cost of employment (i.e., lower wages). If an abundance of immigrants are obliged to work for low wages, employers have the bargaining advantage. If immigrants are few, however, employers are forced, as the economist Sumner Slichter put it, “to adapt jobs to men rather than men to jobs.”59 And while there is some evidence to suggest that immigrants are working jobs that Americans aren’t willing to do, more evidence suggests that it’s not a matter of unwillingness to do the job, but rather a matter of unwillingness to do the job at that wage.60, 61

What none of this means, however, is that low-killed immigrant labor is necessarily bad for the economy at large. In fact, one of the chief benefits of immigration is low-cost goods. A broad body of economic literature suggests that immigrants, by expanding the labor force, help keep prices lower for many goods and services. Even more encouraging is the fact that their downward effect on prices is not wholly a function of paying workers less. Research62 by the United Food and Commercial Workers union indicates that, on average, pay to production workers accounts for only about four percent of the price of goods. Therefore, a 25 percent decrease in wages would cause only a one percent increase in prices.

While the majority of research suggests that immigration lowers consumer prices, there are cases where the opposite is true. For goods that cannot be easily scaled, like homes, the cost tends to increase when a market is suddenly flooded with a large influx of immigrants who drive up demand for a fixed asset where the supply cannot expand quickly. Speaking before the House Committee on Oversight and Accountability in September 2024, Steven A. Camarota, Director of Research at the Center for Immigration Studies, was asked to summarize the studied effects of immigration on the cost of living. His congressional testimony detailed how immigrant competition for housing—both rental and ownership—places upward pressure on prices, particularly in urban areas, where a five percent increase in the immigrant population costs “the average household headed by a U.S.-born person … a 12 percent increase in rent, relative to their income.”63

If we only look at macroeconomic indices like GDP, stock market performance, or consumer spending, it seems safe to say that even if low-skilled laborers suffer a reduction in wages, increased immigration is good for the overall economy. But an economy is not just a balance sheet—it exists within a society, and when social cohesion weakens, economic growth alone cannot sustain a nation.

The Effects of Immigration on Society, Culture, and Social Cohesion

In 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt commissioned a report on the effects of immigration. Four years later, in 1911, a bipartisan committee headed by Senator William Dillingham, published a 41-volume study on the issue.64 In it, they concluded that:

The recent immigrants [have] been reluctant to identify themselves with the unions and to pay the regular dues under normal conditions, thus preventing the labor organizations from accumulating large resources for use in strengthening their general conditions and in maintaining their position in time of strikes. … [U]sed as strike breakers, they have taken advantage of labor difficulties and strikes to secure a foothold in the industry, and especially in the more skilled occupation. … [C]orporations, with keen foresight, had realized that by placing the recent immigrants in these positions they would break the strength of unionism for at least a generation.

What came to be known as the Dillingham Commission—famous for its data-driven analysis—set American immigration policy over the next half-century. Observing how Gilded Age oligarchs preferred to pack their factories with a motley mix of immigrants who had no common language, no common traditions, and no common sense of solidarity, the commission laid bare something that Carnegie, Rockefeller, and the rest had long understood—social cohesion is the backbone of labor’s power. Strong labor movements rely on shared identity, communication, and trust, which vanish when a workforce is fractured along linguistic and cultural lines. A factory floor where workers can’t communicate is a factory floor where strikes never get off the ground. Immigration wasn’t just a source of cheap labor for industrial barons—it was a strategic tool to divide, weaken, and conquer the working class.65, 66 As Friedrich Engels noted:“[the] bourgeoisie knows … how to play off one nationality against the other: Jews, Italians, Bohemians, etc., against Germans and Irish, and each one against the other.”

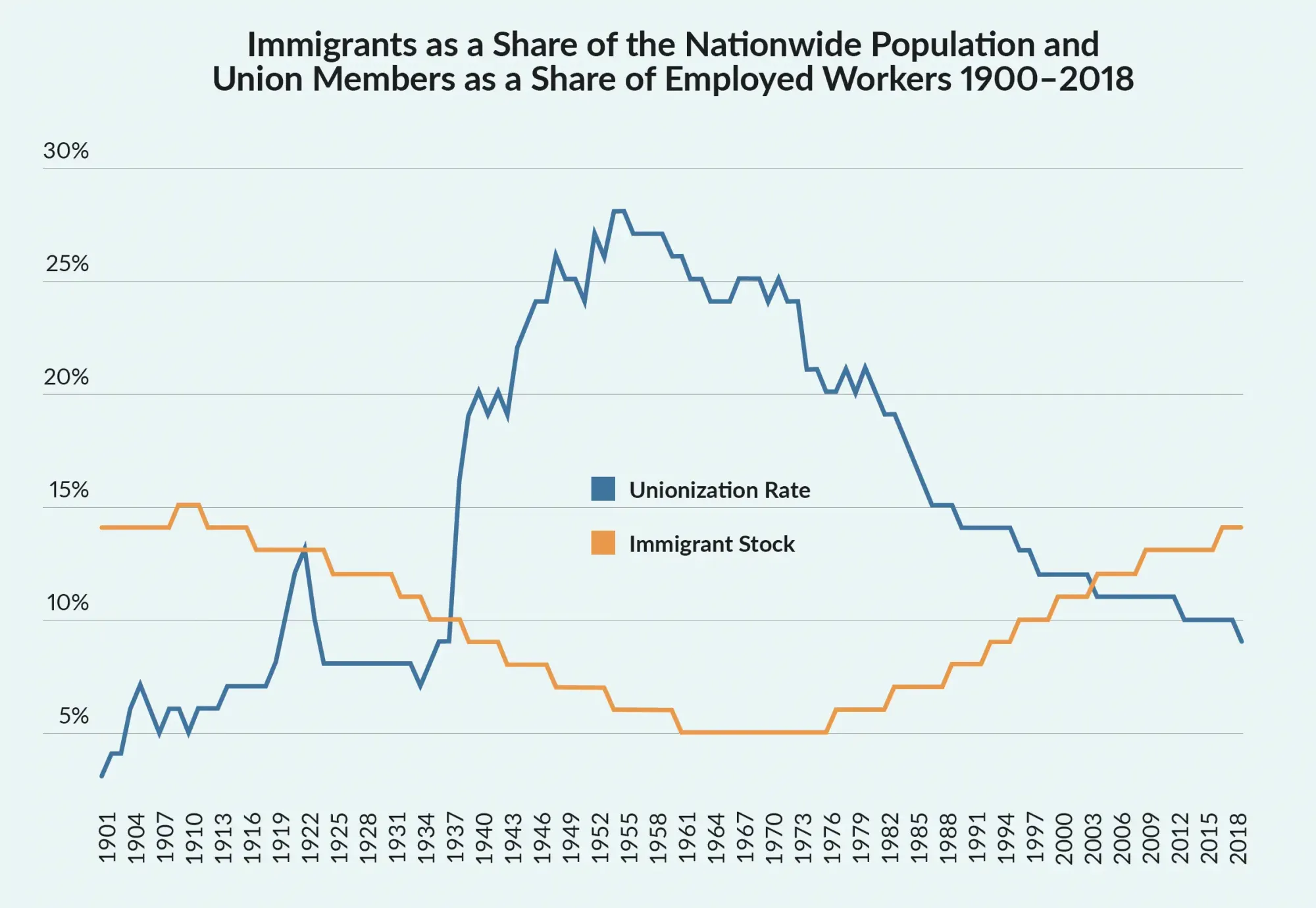

Last year (2024) the percentage of foreign born reached the highest levels in our nation’s history (over 15 percent), surpassing those of the last massive immigration wave to the United States in the late 19th century.67 A study by the Cato Institute68 found that immigration reduced union membership by 5.7 percent between 1980 and 2020, accounting for 29.7 percent of the overall decline in unions during that period. The authors explain that because “immigrants have a lower preference for unionization and because immigrants increase diversity in the workforce that, in turn, decreases solidarity among workers and raises the transaction costs of forming unions.” Further, unions derive their power from the ability to withhold labor, forcing employers to negotiate on wages and conditions. But when a constant influx of new workers stands ready to replace those on strike, that leverage collapses. It is no coincidence, according to The New York Times columnist David Leonhardt, that union strength and participation precipitously declined after the 1965 immigration bill.69

The economy, like unions, both shapes and is shaped by human behavior. Disentangling the economic effects of immigration from its effect on our institutions, culture, and politics—each of which loop back to re-affect society in often unexpected ways—is impossible. Calculating the fiscal impact of immigrants by isolating variables, like unemployment or the price of goods, without considering broader questions like how immigration impacts who we elect to government or what we think of our neighbors is like measuring physical health without regard to the patient’s mental well-being. However great the impact of immigration is on wages, it is unlikely to outweigh the impact of the elected president’s tax policy or the nation’s social trust. Indeed, it might be said that immigration is good for the economy if it unites Americans behind good economic policies, and it is bad for the economy if it undermines collective action in a way that leaves us vulnerable to bad politicians who exploit the discord.

The social effects of immigration might be compared to American football—“the ultimate team sport.” With a 53-man roster and the most intricate coaching bureaucracy in all of sports, the best football teams are rarely those with the richest owners or most Pro Bowl players. In football, the best teams are those with the best culture. Bill Belichick, widely considered the greatest head coach in NFL history, was notorious for cutting star players and replacing them with less talented ones who better fit the team mentality. One sign hung above all others in the Patriots locker room: “Mental toughness is doing what’s right for the team even when it’s not what’s best for you.”70 Similarly, Sean McVay, Super Bowl winning head coach of the L.A. Rams, has said that he has only one rule for his team, “we over me.”71

Countries are in many ways like football teams. Success depends less on individual ability and more on a shared identity, unifying leadership, and the willingness to put collective interests ahead of personal gains. A team—or a nation—fractured by self-interest falls apart. The political sociologist Robert Putnam72 has argued that the single most important predictor of national prosperity—more than wealth, technology, or education—is social capital, a measure of the norms and networks that enable people to act collectively. High social capital societies produce stronger institutions, greater civic engagement, and overall increased trust among their citizens. Putnam writes:

School performance, public health, crime rates, clinical depression, tax compliance, philanthropy, race relations, community development, census returns, teen suicide, economic productivity, campaign finance, even simple human happiness—all are demonstrably affected by how (and whether) we connect with our family and friends and neighbours and co-workers.73

At its core, every cooperative system—economic, political, social, or otherwise—relies on trust. Modern capitalism, for example, is built on the collective faith that a dollar bill is worth what we all agree it’s worth. As Franklin D. Roosevelt explained in his first ever fireside chat74 to the American people: “There is an element in the readjustment of our financial system more important than currency, more important than gold, and that is the confidence of the people.” More famously, he proclaimed that “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” Without confidence in one another, when fear replaces trust, the very mechanisms that allow a country to function—democracy, markets, even basic public order—begin to erode. If we can’t leave our doors unlocked, we are less likely to sacrifice for our neighbors at the ballot box. Here is Edmund Burke on the matter:

Manners are of more importance than laws. Manners are what vex or soothe, corrupt or purify, exalt or debase, barbarize or refine us, by a constant, steady, uniform, insensible operation, like that of the air we breathe in.

In his book Bowling Alone, Putnam documents the collapse of social capital in the United States since 1970. Indeed, Americans today spend less time with friends,75 have fewer friends to begin with,76 report fewer positive interactions with strangers,77 and experience less frequent human interaction in general.78 We are more distrustful of institutions79 and our fellow citizens and neighbors.80 We also take less active roles in our communities, join fewer clubs, attend fewer dinner parties, go to church less, participate less in local government and are members of fewer sports leagues—including bowling leagues.81 Meanwhile, government agencies at all three levels—local, state, and federal—have also dramatically decreased their investment in public works projects that enhance social capital such as libraries, parks, and community centers. As a result, America is suffering from a surge of what the economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton have called deaths of despair—from alcohol, drugs, or suicide—but which might more accurately be described as deaths due to loneliness.82

Although there are multiple explanations and a host of complex factors contributing to the decline in social capital, one of them is high immigration rates. Putnam’s most recent book, The Upswing, divides the last 150 years of American history into three distinct eras. From a hyper-individualistic “me” culture in the Gilded Age to a collective “we” culture beginning at the turn of the 20th century and then back to a new “me” era post the 1960s. Curiously, these divisions map almost exactly onto historical shifts in American immigration policy (i.e., mass immigration during the low social capital Gilded Age, strict restriction during the high social capital Progressive Era, and then again a second wave of mass immigration in the current Neoliberal Era).

A low-trust society doesn’t debate policy—it searches for enemies.

Immigration’s effect on social capital is well-documented. There are two main explanations for how immigration is expected to affect social capital. The first, known to researchers as the “conflict hypothesis,” requires us to distinguish between two types of social capital: bonding and bridging. Bonding social capital refers to social ties within groups that share a similar background (e.g., families or cultural or ethnic ingroups) and exclude non-members. The Jewish diamond district in New York City, for example, relies on tight networks of Hasidic Jews who sacrifice and collaborate to promote their business among their own community while tending to exclude those who are not members of the ingroup.83

Bridging social capital, on the other hand, generates social networks that transcend differences across groups with different cultural, religious, or ethnic backgrounds. The conflict hypothesis predicts that increased diversity can, under certain conditions, intensify bonding social capital and tighten ingroup networks.84 Under these conditions, collective action and pursuing the common good can become increasingly burdensome. In some cases85 increased diversity has been shown to not only reduce trust between groups but also within ingroups. In the extreme,86 this can cause such a breakdown of overall social capital that no one trusts anyone and parochialism runs riot as various factions are pitted against each other. Putnam’s research supports the conflict hypothesis, describing the effect of too much immigration as a sort of “hunkering down.”87

The conflict hypothesis is also supported by evolutionary theory, which suggests that human sociality is built on “parochial altruism”88—the evolved tendency to direct altruism preferentially towards one’s own group and eschew interactions with outsiders. If natural selection prefers this type of altruism, then fostering bridging social capital becomes a delicate balancing act that runs against ancient and deep-seated biases. Left unchecked, this behavior can turn hostile when there is competition for scarce resources between groups89 and helps to explain why working class Americans, who are in less of a position to “share the wealth,” hold more bigoted opinions of immigrants.90

A competing theory to the conflict hypothesis is commonly called the “contact hypothesis” of immigration. It predicts that under certain conditions, exposure to people from different backgrounds decreases prejudices and over time increases overall social capital.91 Perhaps the most foundational study supporting the contact hypothesis is research on the integration of Black and White soldiers during WWII.92 The key finding is that White soldiers who had more contact with Black soldiers were more open to serving with them in mixed race platoons. But context here is crucial. Differences between American Blacks and Whites serving in the military are trivial compared to those between immigrants and a host country’s native citizens. In the case of the soldiers, both Whites and Blacks shared a common history, culture and language on top of what are probably the most important facts: They were situated in a strict and clear hierarchy (i.e., the military), shared a common enemy, and were putting their lives on the line for a common cause. Outside of these specific conditions, the literature finds little evidence for the contact hypothesis.93

A country can absorb large numbers of immigrants, but not if their difference is their most defining characteristic.

My own research94 tracks the effects of low social capital on our politics, finding that increased isolation and the breakdown of social networks can radicalize voting behavior and reshape electoral coalitions. In Germany, for example, support for right-wing populist parties has been associated with individuals who perceive ethnic outgroups as competitors for scarce resources.95 Another study in Western Europe reveals that “the electoral success of right-wing populist parties among workers seems primarily due to cultural protectionism: the defense of national identity against outsiders [i.e., immigrants].”96 A low-trust society doesn’t debate policy—it searches for enemies.

In summary, the dangers of too much diversity distinctly outweigh those of too much immigration. A country can absorb large numbers of immigrants, but not if their difference is their most defining characteristic. The United States, in this respect, is fortunate that the southern border is overflooded with immigrants from culturally compatible nations like Mexico and those in Central America, who, unlike the refugees and economic migrants from the Greater Middle East who overwhelmed Europe in recent years, have proven to be exceptional integrators.97

The Ideological Nation

In his final speech as President of the United States, Ronald Reagan shared with the American people an excerpt from a letter recently received:

You can go to live in France, but you cannot become a Frenchman. You can go to live in Germany or Turkey, but you cannot become a German or a Turk. But anyone, from any corner of the Earth, can come to live in America and become an American.98

The United States is what political scientists and historians describe as an “ideological nation.”99 While most countries have been bound by shared ancestry and geographic borders (i.e., “blood and soil”), the United States is bound by a shared commitment to abstract principles—freedom, equality, opportunity, and so on. In the United States, becoming an American requires none other than that. To be American you do not have to be born here or even speak fluent English, you just have to become “one of us” and celebrate the 4th of July. And for all the accusations of xenophobia or intolerance, many of which hold truth, the evidence is clear: No other country attracts, welcomes, and ultimately integrates their foreign-born population better than the United States.

The right must recognize that cultural assimilation is a process, not an immediate transformation.

A study by the Manhattan Institute100 rates the United States as second to only Canada in its assimilation index, which measures the degree of similarity between native and foreign-born populations across various economic, cultural, and civic indicators. The primary reason for Canada’s ranking over the U.S., however, results from its higher rate of naturalization. And while it is surely a great benefit, it is less a measure of how accepting and inclusive the culture is, and more a reflection of different policy design. To extend the argument, America demonstrates an unrivaled ability to absorb and assimilate immigrants whose cultural orientations differ dramatically from its own, such as individuals from Muslim societies.

The United States is a nation of immigrants. No other nation has taken in more, no other economy has given them more, and nowhere else have immigrants been so seamlessly woven into the social fabric as in the United States. America’s unique ability to absorb a large proportion of newcomers is one of its greatest strengths, fueling an economic dynamism and cultural vibrancy unmatched throughout the world.

A lot of immigration is beneficial when it helps to offset the demographic crises, as countries such as China,101 Japan,102 and many in Northern Europe103 have fallen far below replacement levels. South Korea104 has a total fertility rate of 0.72 (2.1 is needed to maintain a population) and appears headed for extinction within just a few generations. But a lot of immigration works best when immigrants integrate into their new nation, when they share in the national story, embrace common ideals, and feel bound by a sense of collective purpose. In other words, when instead of adding more immigrants to the country, we add—in the case of the United States—more Americans to the country. And our immigration policy works best when it’s built on reality, not ideology—when it acknowledges limits, institutes selection hierarchies, prioritizes Americans, and is willing to adapt.

Perhaps it is time to bring back that old idea of America as “the melting pot,” a national creed that has been abandoned by both the “salad bowl” Democrats—where assimilation is seen as a tool of cultural oppression—and the “build the wall” Republicans—who have embraced their own form of salad bowl separatism, treating immigrants as intruders instead of future Americans. The right must recognize that cultural assimilation is a process, not an immediate transformation, while the left must acknowledge that integration requires more than mere presence—it demands a shared commitment to American ideals. Immigrants must be willing to adopt to American values. Immigration, like any successful relationship, requires reciprocity.

Finally, if the country wishes to continue reaping the rewards of immigration, it must first reaffirm its own identity and decide whether it still believes in the promise of America itself.