The Contradiction at the Heart of Gender Debates

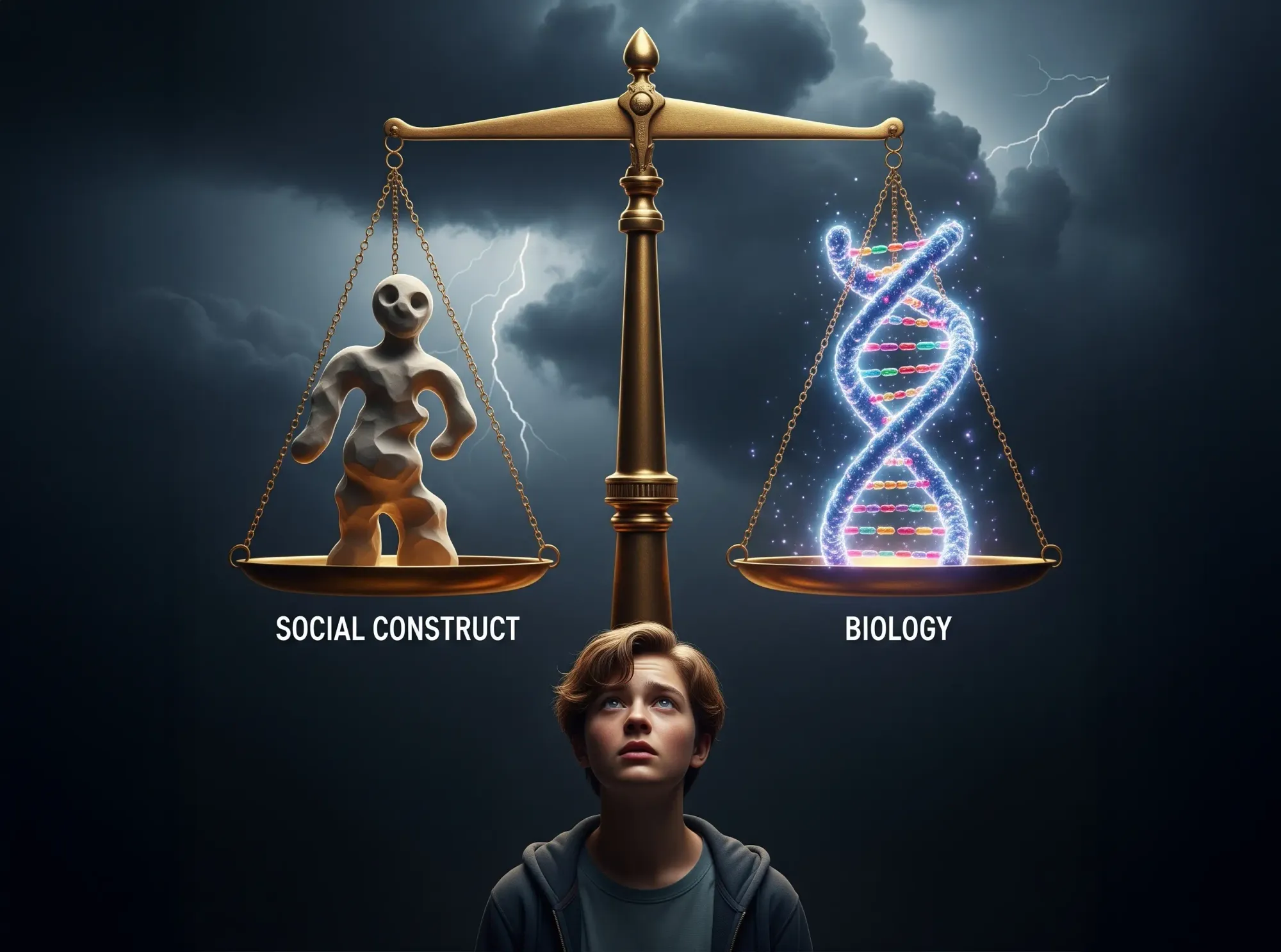

Gender identity has become one of the most pressing–and polarizing–topics in today’s cultural landscape. Major medical associations have embraced a variety of gender-affirming treatments, ranging from counseling sessions to lifelong hormonal therapies and even surgeries. Their rationale is that these interventions help alleviate severe distress among people who experience a disconnect between the sex they were born with and the gender they identify as. In the same breath, however, many of these organizations and prominent voices also describe gender as largely a “social construct”–something molded by cultural norms rather than by biology.

That claim raises a fundamental paradox. If gender truly rests on external expectations, why do some advocates support irreversible medical procedures–especially in children–as a primary response to gender-related distress? On the flip side, if there is a strong biological basis for gender identity, then why do we invoke social factors so frequently? For parents, policy-makers, and health professionals trying to do right by patients, these questions create a tangle of uncertainty. Even more critically, children and teenagers lie at the center of an ethical storm that involves decisions about their bodies, their long-term health, and whether or not they should receive life-changing medical treatments before they’ve reached adulthood.

The Rise of Gender-Affirming Care

Over the past decade, a growing number of adolescents have presented to clinics with gender dysphoria–a term describing psychological distress that arises when someone’s gender identity does not align with their biological sex. Many point to increased visibility on social media platforms, greater cultural acceptance, and shifting diagnostic criteria as drivers of this trend. More public conversations have lowered the stigma that once surrounded topics of gender identity, thereby encouraging more families to seek out professional help.

Even among professionals who see medical interventions as appropriate in specific cases, many urge greater caution when minors are involved.

At first glance, this appears to be good news: it might simply suggest that people who would otherwise suffer in silence are getting care sooner. However, some scientists have cautioned that the scientific basis for rushing into physically transformative treatments–like puberty blockers or cross-sex hormones–is less settled than some believe. While small-scale studies often show that teens may feel better in the short run when they start medical interventions, critics argue that these studies are often limited by small sample sizes, lack of long-term follow-up, or reliance on self-reported outcomes. As a result, the evidence about possible harmful effects, regret rates, fertility loss, and other life-altering implications remains uncertain.1

Even among professionals who see medical interventions as appropriate in specific cases, many urge greater caution when minors are involved. Adolescents, after all, are still navigating a period in life in which personality, preferences, and self-image can change dramatically over just a few years. Some note that a substantial number of children who experience gender confusion eventually choose to align with the sex they were born into, once puberty and mental development progress.2, 3, 4 If that is true for a sizable proportion of youth, it raises serious moral and ethical considerations about guiding them toward irreversible treatments so early in life.

When Minors Are Involved

The tension is magnified when the patient is a child or teenager. Deciding whether a young person should start taking powerful hormones at a time when their brain and body are still maturing is no small responsibility. Adolescents generally have limited capacity to project far into the future and weigh long-term risks against short-term relief. This is one reason why society imposes age restrictions on major decisions–whether it’s voting, consuming alcohol, or entering into legal contracts.

Adolescents generally have limited capacity to project far into the future and weigh long-term risks against short-term relief.

In cases where a teen is diagnosed with gender dysphoria, the stakes are exceptionally high. The potential harm extends beyond immediate side effects: puberty blockers can impact bone density, cross-sex hormones can affect future fertility, and surgeries might remove or alter healthy body parts in a way that can never be reversed. If the teen comes to identify differently in later years–as many detransitioners report–the regret can be profound. These individuals sometimes feel they made decisions they weren’t old enough to understand, pointing to mental health struggles, outside influence, or social pressures that contributed to their choices at the time.5

Another complicating factor is the prevalence of mental health challenges. Many teens presenting with gender dysphoria also have co-occurring conditions such as depression, anxiety, or traits along the autism spectrum. Untangling whether a young person’s discomfort with their sex stems primarily from deeper psychological challenges or a deeper disconnect with their body can be a complex task. Some experts worry that prescribing hormones too quickly might mask core issues that should be addressed through therapy or more holistic forms of care.6

Stories of Detransition

Increasing numbers of detransitioners–people who pursued medical treatments to live as the opposite sex and later regretted it–have brought further attention to the potential pitfalls of early intervention. Some of these individuals began taking puberty blockers in early adolescence, moved on to cross-sex hormones in their late teens, and underwent surgeries by the time they were barely out of high school. Later, in their early twenties, they realized that the hormonal changes and surgeries failed to resolve underlying distress or that their sense of identity shifted back toward their birth sex.

Though detransitioners appear to be a minority within the broader transgender community, their stories highlight the importance of a measured approach–especially in those critical teenage years. Their experiences point to the need for thorough mental health evaluations, emphasis on informed consent, and a recognition that identity can evolve, particularly in young people.

A Biological Perspective

To understand why many observers question the notion of gender as purely a social construct, it helps to look at biology. From the earliest moments of development, sex is written into every cell of the body. Humans typically have XX chromosomes for females and XY for males. While there can be rare variations in these chromosomal patterns, the overwhelming majority of people follow this binary at the genetic level. Each cell in a person’s body is aware of whether it belongs to an XX or XY individual because the underlying genetic code instructs the cell to behave in a sex-specific way.

Hormones also come into play. During fetal development, surges of testosterone in an XY fetus help shape not just the external genitalia but also the brain’s circuitry. Similarly, the absence or lower levels of these androgens in XX fetuses contribute to a different developmental trajectory. These hormonal influences create meaningful differences in structure and function that can last a lifetime and are often resistant to external social forces. Indeed, researchers have found that certain regions of the brain exhibit sex-specific characteristics that align more closely with genetic and hormonal history than with cultural conditioning.7

Further illustrating the depth of these biological underpinnings is the fact that hormonal shifts continue after birth. In XY infants, testosterone spikes in the early months of life, aiding further development of neural pathways associated with male-typical behaviors. In XX infants, the lower androgen levels may guide different patterns of play and interaction. In adolescence, surging sex hormones activate and solidify some of these neural circuits, reinforcing characteristics that first took shape in the womb.

One line of thought suggests that variations in prenatal hormone exposure can lead to a brain-body mismatch.

Some individuals, however, do experience a mismatch between their deeply felt gender identity and their biological sex. The question is whether this incongruence arises primarily from social influences or whether it has biological underpinnings of its own. One line of inquiry suggests that variations in prenatal hormone exposure can lead to a brain-body mismatch in which the individual’s internal sense of self aligns more closely with a different sex than the one indicated by their chromosomes. This perspective offers a potential scientific explanation for those who say they were born into the wrong body and cannot simply adopt a different gender role by choice.

Contradictions in the Current Approach

Despite this strong biological evidence, many medical or advocacy organizations continue to describe gender as mainly a social construct. Meanwhile, they often support medical treatments that target the body’s biology–hormones, genital structures, secondary sex characteristics–as the primary path to alleviate distress. This creates an inherent contradiction: If gender is almost entirely shaped by social learning, then extensive counseling and social support might be enough to alleviate discomfort. But if there is a robust biological component, it undercuts the claim that gender is simply imposed by society.

The contradiction becomes glaring in an age where more and more young people identify outside the male-female binary. If someone’s gender is fluid or shifts across multiple categories, does permanently modifying the body fully serve that fluidity? Or might that reinforce the notion that a body needs to be “fixed” to match one of two possible categories? The debate is complicated and often emotionally charged, especially when real lives and futures are at stake.

For many medical professionals, the goal is to reduce suffering while respecting each individual’s journey. Yet the limited data about long-term outcomes–coupled with rising numbers of teens seemingly suddenly identifying as transgender–continues to raise doubts. Clinicians are caught between wanting to show compassion and facing the possibility that some adolescents might adopt a trans identity due to social pressures, mental health struggles, or other factors that do not necessarily involve a genuine and consistent biological mismatch.

Ethical Dilemmas

At its core, the debate about medical interventions for minors is ethical. It revolves around questions of capacity to reason, informed consent, and the principle of “do no harm.” If a child is too young to comprehend long-term repercussions–such as reduced fertility, ongoing hormonal dependencies, potential surgical complications, and the chance of regretting irreversible procedures–then how can society or the medical establishment justify greenlighting interventions that may be permanent?

Parents find themselves in a difficult position. They want to do what’s best for a child who might be in crisis, but they also worry about making decisions that cannot be undone.

Parents find themselves in a difficult position. They want to do what’s best for a child who might be in crisis, but they also worry about making decisions that cannot be undone. Healthcare professionals, meanwhile, face pressure from advocacy groups who see any delay as cruel or bigoted, because it leads to the transgender teen irreversibly developing characteristics of the sex they do not identify as, such as broad shoulders or a strong jawline (in the case of Male-to-Female transgender individuals) or breasts and wide hips (in the case of Female-to-Male transgender individuals). Some clinicians also worry that failing to address underlying mental health conditions can lead to misguided interventions–young people may conflate discomfort with their bodies, or alienation from peers, with identifying as a different sex.8

In some cases, courts step in when parents, medical teams, or minors disagree, emphasizing just how unsettled this territory is. Lawsuits alleging insufficient counseling, medical malpractice, or inadequate disclosure of potential risks have underscored the importance of robust safeguards. These cases aren’t about demonizing trans people; rather, they question whether the current model has moved too quickly, especially for children who may not be ready for such significant, life-altering decisions.

In some cases, courts step in when parents, medical teams, or minors disagree, emphasizing just how unsettled this territory is.

Case Examples

Real-life narratives drive home the human stakes more powerfully than theoretical debates. One individual was raised as a girl after a severe accident in infancy destroyed his male genitalia. Physicians at the time believed that a child’s gender identity could be molded almost entirely by environment, so they recommended surgically creating female anatomy and raising the child as a girl. Despite an upbringing filled with dolls, dresses, and female pronouns, the child persistently gravitated toward male behaviors and interests. As an adolescent, he found out the truth of his birth sex and later decided to live as a man, though not without enduring serious emotional trauma.

Similarly, a number of detransitioners report that their early experiences mirror a pattern of underlying depression, anxiety, or social struggles that were not fully addressed. Only after physically transitioning–and discovering that those internal issues remained–did they come to question whether medical intervention was the right path.

Plenty of transgender adults stand by their decisions and report profound relief at transitioning. Their successes should not be dismissed.

Of course, plenty of transgender adults stand by their decisions and report profound relief at transitioning. Their successes should not be dismissed. But the existence of regret underscores the seriousness of these interventions and the absolute necessity for thorough, long-term evaluation before proceeding with young patients.

Conclusion

Today’s debates over gender-affirming care illuminate an underlying contradiction: many experts frame gender as a social invention, yet they simultaneously support biologically altering interventions. This clash mirrors a larger cultural tension. On one hand, we yearn for a world where people are free to express themselves in any way they choose, unbound by stereotypes. On the other, we acknowledge that each cell in our body is branded male or female at a genetic level, and that hormones shape fundamental aspects of who we are.

In this ambiguous space, children and teens deserve the highest degree of caution and compassion. That doesn’t mean denying genuine gender dysphoria or withholding supportive counseling.

In this ambiguous space, children and teens deserve the highest degree of caution and compassion. Their brains are still developing, and their sense of self is evolving at an age when they may not fully grasp the consequences of permanent medical treatments. That doesn’t mean denying genuine gender dysphoria or withholding supportive counseling. Rather, it means honoring both the psychological dimension of identity and the profound biological processes at work underneath it all.

No one has all the answers about the best path forward–especially in a field where emerging research grapples with rapid social change. But at minimum, any course of action should recognize that while social context matters, human biology is not as malleable as some suggest. By acknowledging the biological aspects of sex and gender from the beginning, we can better weigh the ethics and long-term implications of altering that biology in an attempt to ease youthful distress. It is precisely because the stakes are so high that a more careful, evidence-based, and individualized approach is vital. When real lives hang in the balance, certainty cannot come from ideology alone–it must be grounded in clear, comprehensive insight into both body and mind.