Interviewing the Children of Nazi Leaders: Guilt, Trauma, and the Legacy of Atrocity

History can be a mirror or a wall. For many people, it’s a mirror only when they see their own family reflected in it—an ancestor who fought in a war, survived a famine, or emigrated under duress. For others, history is a wall they can never climb. The view on the other side is fixed: the past is not what was done to them, but what their parents or grandparents did to others.

That is the reality I discovered when interviewing the sons and daughters of leaders of the Third Reich.

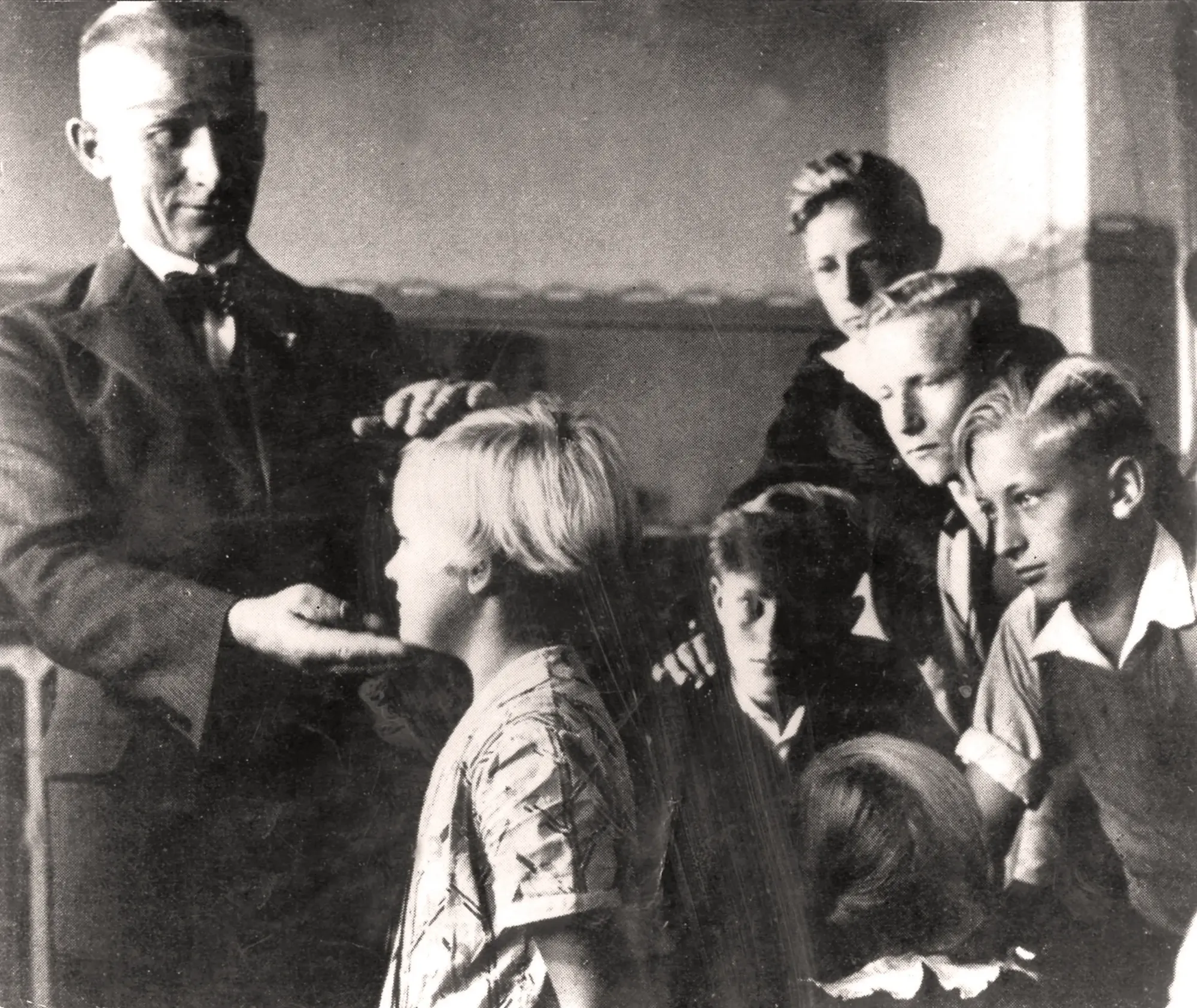

When I began work on Hitler’s Children, I was not looking for new evidence about what happened in the Nazi Holocaust. The bureaucratic record of the Third Reich was already vast—memos, orders, trial transcripts, camp rosters—the Germans were masters of documenting their crimes.

What I wanted was something the archives could never provide: a human portrait of the children of top Nazis, the men and women who grew up in the shadow of fathers whose names had become synonyms for evil.

I wanted to know: What is it like to love a parent whom the world knows as a war criminal? How do you form a sense of self when the world has already decided who you are—and it is an identity you neither chose nor can easily shed? What happens to ordinary human relationships—marriage, friendship, parenthood—when your family name carries an explosive moral charge?

Those questions took me across Germany and Austria and into conversations that were often guarded, sometimes raw, and occasionally redemptive. Some doors never opened. Some opened a crack and then slammed shut the minute I explained that I could not promise a sympathetic portrait. A few opened wide, and what came out was not a clean confession or a tidy arc toward reconciliation but something more human: ambivalence, anger, loyalty, shame, defiance, grief. What emerged was not a single “Nazi progeny” experience but a spectrum of responses to inherited guilt.

Knocking on Closed Doors

Tracking down the children of the regime’s inner circle required patience and a tolerance for being told no. Some had changed their surnames and slipped into anonymity. Others had moved abroad, where the name on their passport did not immediately freeze a room. Many were instantly hostile when I contacted them. They assumed—not unreasonably—that I was there to condemn their parents or to dredge up what they had spent decades trying to bury.

I learned quickly that the children of perpetrators could be as guarded as the children of victims. I knew many of the latter intimately because I had earlier co-authored a biography of Nazi Dr. Josef Mengele. I had spent countless hours with concentration camp survivors about their experience and the trauma it had left them. When I approached the children of the perpetrators, I discovered some had been burned by journalists who came for sensational quotes and left nuance on the cuttingroom floor. Others feared the moral judgment of strangers or the social cost in their own communities if they were seen as disloyal to family.

A few, though, agreed to speak. Some said they wanted the truth to be known while they were still alive. Others hoped that narrating their story aloud might lighten the weight they had carried in silence. What I heard, over time, was less a series of disconnected biographies than a set of recurring moral dilemmas.

The Spectrum of Inherited Guilt

To make sense of what I was hearing, I came to think of my interviewees along four rough lines. These are not scientific categories—lives overflow categories—but they capture distinct ways the various individuals navigated the same shadow.

1. The Rejectors. These were the sons and daughters who saw their fathers’ crimes with scorching clarity and devoted their lives to exposing them. Niklas Frank, son of Hans Frank—the Nazi Governor-General of occupied Poland—was the most uncompromising. He called his father a “spineless jerk,” wrote a book that dismantled the family mythology, and made no room for sentimentality in the face of historical fact. “You don’t put love for your father above the truth,” he told me. The choice for him was not between love and hate but between complicity and moral independence.

2. The Defenders. At the other end of the spectrum were those who insisted their fathers were maligned by history or punished beyond proportion. Wolf Hess defended his father, Rudolf Hess, Hitler’s deputy, as a “man of peace” betrayed by political enemies and victors’ justice. For Wolf, to defend his father was to defend himself from the conclusion that he was the son of a villain. The defense became a scaffold for identity, a way to live in the world without constantly negotiating contempt.

3. The Divided. In the middle were those who could neither fully condemn nor fully exonerate. Rolf Mengele—son of Dr. Josef Mengele—met his father only twice after the war. Rolf was sixteen the first time, when his father traveled from his South American hideaway for a skiing vacation in the Swiss Alps. Rolf’s mother had told him his real father had died in war, and the visitor was “Uncle Fritz.” Three years later he learned that Uncle Fritz was in reality his father and he learned about his crimes. He only met him again when Rolf was 33, a visit to South America to confront him about Auschwitz. The elder Mengele closed that door, telling his son never to question him about what happened at the camp and what led to the prisoners dubbing him the “Angel of Death.”

Public history sees uniforms and titles. Private memory remembers the warmth of a hand.

Rolf did not deny his father’s atrocities; he had studied the documents as had everyone else. However, his sense of loyalty to his family had fractured the moral clarity that comes easily to people who never face the person behind the infamy. Rolf carried two incompatible truths: the father he barely knew and whom his family loved and the historical perpetrator he could not defend.

4. The Transcenders. Finally, there were those who took the moral debt they inherited and turned it outward—into a public ethic. Dagmar Drexel’s father was not a senior Nazi official but instead one of the murderous Einsatzgruppen, the mobile death squads that killed more than a million civilians. She chose the path of engagement and reconciliation, visiting Israel, supporting dialogue, and insisting that her children and grandchildren be raised in the light of historical truth. Dagmar hoped, as many did, that if her generation did the hard work, the third generation might be free of the burden.

These categories blur at the edges. People moved along the spectrum over time—hardening or softening as new documents and eyewitness accounts surfaced, as they aged, as their own children asked harder questions than journalists ever could.

Taken together, however, the spectrum reveals the variety of human strategies for living with the inheritance of atrocity.

The Double Life of Memory

For outsiders, the hardest truth to grasp may be the most banal: perpetrators are still parents. A man who signed deportation orders may also have read bedtime stories, taught a child to swim, or taped the wobbling seat on a first bicycle. Public history sees uniforms and titles. Private memory remembers the warmth of a hand, the tone of a voice in the kitchen at night.

Reconciling those two realities—public monstrosity and private tenderness—was the central torment for many I met. Some resolved it by letting historical fact erase the personal. They repudiated the father and severed the line. Others clung to the personal, even when it meant being accused of denial.

Guilt is about actions; shame is about identity.

Edda Göring, devoted to her father’s memory, described Hermann Göring as generous and loving. She did not deny the crimes of the regime for which he was one of its top leaders but resisted the idea that her father had been a fanatic. To critics, that sounded like apologetics. To her, it was loyalty to the man she knew as a kindly father.

The tension here is not reducible to “truth versus lies.” Rather, it is a collision of kinds of truth—the truth of documented atrocity and the truth of attachment, which does not yield easily to hard facts. I came to believe that part of the work of reckoning is sometimes learning to hold both truths at once without letting either evaporate the other.

Shame, Guilt, and the Psychology of the Second Generation

Psychology offers a vocabulary for what I heard. The “intergenerational transmission of trauma” is well documented among the children of victims—especially Holocaust survivors—where symptoms include anxiety, hypervigilance, and a deep mistrust of institutions. Among the children of perpetrators, I discovered that a related but distinct process plays out. Their inheritance is not injury but stigma—the corrosive effects of shame, moral ambiguity, and the fear that others see an invisible mark.

Guilt is about actions; shame is about identity. One can confess guilt and make amends. Shame, by contrast, whispers that one is something tainted. Several interviewees spoke of carrying a “name that enters the room first.” It affected romance (when to disclose the name), employment (whether a boss would know the family and decide against them), and decisions about parenthood (whether to have children at all).

Coping strategies reflected familiar psychological defenses. Some changed their names or emigrated—geographic cures for a moral biography. Others chose radical transparency—publicly condemning their fathers in books and interviews to reclaim their own moral agency. A third group practiced radical silence, hoping that if the topic never arose, the past might recede on its own. It never did. Silence, I learned, is a temporary dam. The water rises behind it.

How Family Systems Carry History

Beyond the individual psyche lies the family system—the ways stories are told or not told, the rituals of commemoration or erasure. Some families preserved elaborate mythologies in which the father had resisted orders, saved a Jewish neighbor, or known nothing about the machinery of murder.

The myths were often anchored in a single ambiguous episode—an order not carried out, a mild reprimand from a superior—that became the seed for an alternative history.

Other families split. Siblings took opposing stances. One condemned; another defended. At holiday meals, the past was both present and forbidden.

“Intergenerational trauma” named not only what moved from parent to child but what moved from child back to parent: a judgment the older generation could not bear.

The emotional economy of those households looked familiar to anyone who has studied families marked by addiction or scandal: unspoken rules, competing narratives, and a tacit agreement that love depended on staying within one’s assigned role.

Children who broke the family line—who published a denunciation or appeared in a documentary—sometimes became moral exiles among their own kin. That rupture was the price of telling the truth as they saw it. In those moments, “intergenerational trauma” named not only what moved from parent to child but what moved from child back to parent: a judgment the older generation could not bear.

Social Mirrors: Schools, Workplaces, and the Public Gaze

The burden was not only private. Society itself became a mirror in which these children saw themselves reflected, often in distorted ways. Several spoke of the quiet pause when a teacher or colleague recognized the surname—and then the question that followed, carefully phrased to sound neutral but freighted with suspicion: “Any relation to … ?” In adulthood, some learned to bring it up first, defanging the question with a practiced sentence—“Yes, I’m his daughter; no, I do not share his politics”—and moving on before the conversation stalled.

In public life, the reception depended on the role they chose. The rejectors found a kind of moral home among activists and historians. The defenders found communities that resent “victors’ justice.” The divided and the transcenders navigated lonelier paths, neither embraced by partisans nor comfortable with silence.

What Changes With Time—and What Doesn’t

We sometimes imagine that moral burdens fade in predictable half-lives. In my experience, time changed the tone but not always the weight. As my interviewees aged, many reported that reckoning deepened, not because new facts appeared but because their own children asked better questions.

The third generation—further from the emotional bond and closer to the educational curriculum—refused family mythologies in a way the second often could not. “Grandpa couldn’t have known,” a parent would say. “But he was there,” a teenager would answer.

Anniversaries, documentaries, and new archival releases periodically reset the conversation. A case reopened, a grave discovered, a diary authenticated—and the private work of reconciliation was hauled into public light. At those moments, people who had made peace with their own narrative found themselves having to make peace again, this time with an audience.

Comparative Frames: Not Only Germany

The Nazi case is singular in scale and intent, but the dynamics I heard are not unique. Descendants of slave owners in the American South wrestle with family papers that list human beings as property and calculate children as “increase.” In post-apartheid South Africa, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission exposed a generation of children to testimony that shattered family legends. In Rwanda, the gacaca courts forced communities to confront the fact that génocidaires were not abstract monsters but neighbors—and often fathers. Across the former Yugoslavia, the International Criminal Tribunal’s judgments collided with nationalist narratives passed down at kitchen tables.

In all these contexts, the same questions surface: Am I responsible for the sins of my father? Can I love my parent without condoning their crimes? What do I owe to victims and their descendants? How do I build a life that is truly my own?

The answers vary by culture and circumstance, but the structure of the dilemma is recognizably human.

Mechanisms of Transmission: How the Shadow Travels

If “intergenerational trauma” names an outcome, what are the mechanisms? Scholars point to at least four:

Silence. When families refuse to speak, children fill the vacuum with fantasy or shame. The mind abhors a narrative void. In several households I encountered, silence was the loudest sound in the room. It produced neither absolution nor forgetfulness—only rumination.

Mythmaking. The stories families tell—of resistance, ignorance, or necessity—shape the moral horizon. Even a small act of decency can be inflated into an alibi. Conversely, some families cultivate a punitive myth of inherited stain, a fatalism that imprisons the young in a script they cannot revise.

Ritual and Place. What families visit—or avoid—matters. One daughter told me she had been taken to battlefields but never to camps. Another said the first time she saw the Nuremberg courtroom, she felt she had stumbled into a photograph that had been waiting for her.

Rituals of remembrance can either widen or narrow moral imagination.

The second generation experiences a kind of indirect moral injury: an injury not from what they themselves did but from what knowing does to them.

Institutional Echoes. Schools, museums, and media frame the past in ways that either invite reckoning or permit evasion. A curriculum that skips over the depth and breadth of atrocities—as has happened in many academic settings when it comes to the Hamas terror attack of October 7—makes it easier for descendants to imagine their relatives are free of any responsibility.

Institutions can either dignify the moral labor families attempt or tempt them with a ready-made script of innocence.

Moral Injury and the Cost of Knowledge

“Moral injury”—a term developed to describe soldiers who feel they have violated their own ethical codes—offers another lens. The second generation experiences a kind of indirect moral injury: an injury not from what they themselves did but from what knowing does to them. Knowledge damages one’s relationship to a beloved parent; truth injures attachment.

Some choose not to know much. Others choose to know everything and live with the ache. One daughter, who had read deeply in trial transcripts, said that learning the exact logistics of a deportation under her father’s authority broke something in her. “I used to think there must have been chaos,” she said. “It was worse—there was order.”

For her, the injury was precision—the bureaucratic elegance of evil.

Choosing Children: Reproduction Under a Shadow

A notable fraction of those I interviewed had chosen not to become parents. The reasons varied: fear of passing on a name, a desire to end a line, uncertainty about what one could say to a child who asked, “Who was my grandfather?” One son told me that he chose not to become a father because he could not bear to pass on a story line he had never been able to fully explain.

None believed in genetic guilt. The concern was narrative. Parenthood would require mastering a story they themselves had not yet mastered. Others chose to have children precisely as a defiance of history—an insistence that a life could be built that was neither repetition nor repudiation but revision.

If we want to interrupt the transmission of harm—whether its currency is trauma or shame—we must map the routes it travels.

These decisions often intersected with partners’ views. Some marriages could not bear the weight of history. One woman described the look on a fiancé’s face when he first grasped the details of her father’s role.

“It wasn’t revulsion,” she said. “It was calculation. He was calculating whether he could carry it with me.” The engagement ended.

The Skeptic’s Task: Between Verification and Empathy

A skeptic acknowledges the limits of memory and the demands of evidence. Interviews with perpetrators’ children are not court records; they are human documents, shaped by self-protection, loyalty, and fatigue. Defensiveness, denial, and selective recall were constants. My job, then and now, is to triangulate: place personal accounts against trial transcripts, diaries, and the scholarship of historians and psychologists.

Skepticism here is not cynicism. The aim is to understand without excusing, to listen without indulging. If we want to interrupt the transmission of harm—whether its currency is trauma or shame—we must map the routes it travels. That map requires both archival rigor and an ear for the ways people live with the past.

Freedom for the Third Generation?

Again and again, interviewees asked whether their children—grandchildren of the perpetrators—could be free. There is some evidence that the burden lightens with distance, especially when the second generation does the work of truthtelling. But it is not inevitable. Silence begets fantasy, and fantasy rarely lands on justice.

The most hopeful conversations I had were with families who had made memory a practice rather than a panic. They visited sites of the crimes together. They read. They argued. They did not ask love to overrule truth or truth to annihilate love. They let both inhabit the same home. In those households, the third generation seemed less haunted and more oriented—not weighed down by a surname but awake to what it should mean to carry one.

A line of Dagmar Drexel stays with me: “Our generation has the obligation to confront the truth. Only then can the next one be free.”

The obligation is not to perpetual penance but to honest narration. Freedom comes not from forgetting, but from telling the story in a way the young can live with.

Living in the Shadow Without Becoming It

The story of the children of Nazi leaders is not only about Germany, nor only about the Holocaust. It is about the universal human challenge of living with a family legacy that collides with one’s moral values. We do not inherit guilt in the legal sense. Yet we can inherit its shadow—in our names, our family stories, our silences, and our choices.

Freedom comes not from forgetting, but from telling the story in a way the young can live with.

The work of a lifetime, for some, is not to step out of the shadow but to learn how to live within it without becoming it. That means choosing accuracy over myth, candor over silence, accountability over performative shame. It means loving a parent, if one can, without lying about him—and refusing to let that love dictate the terms of one’s moral life.

If there is a single lesson my interviews taught me, it is that history is never safely past; it lives inside our most intimate relationships. To reckon with that is not to remain trapped. On the contrary, it is the only way through—an insistence that the very human bonds that transmitted the shadow can also be the ones that transform it.