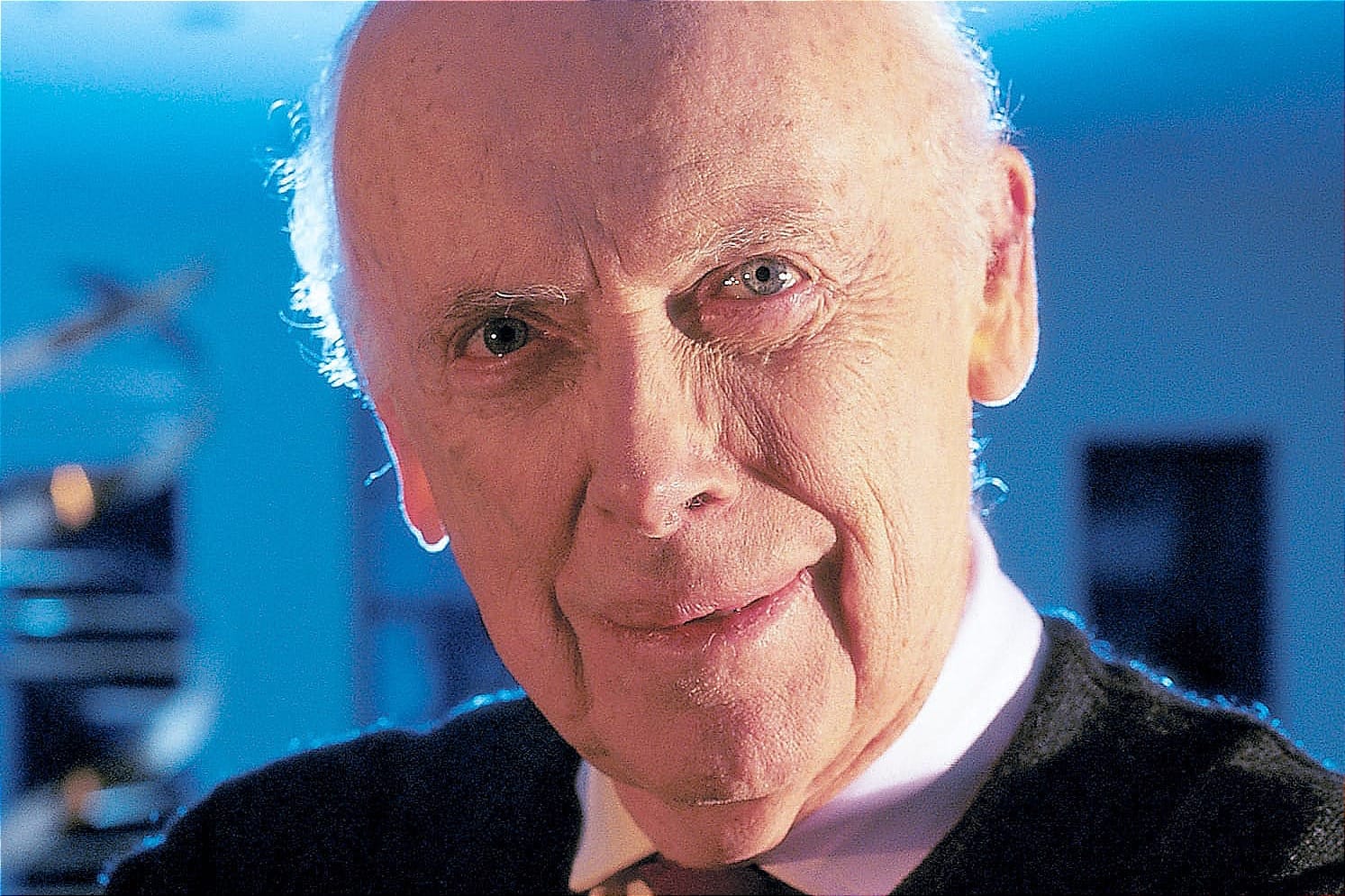

Was James Watson a Racist?

When James Watson died on November 6, 2025, at the age of 97, the news articles that sprang up converged on a verdict: Watson’s co-discovery of the structure of DNA makes him a scientific legend, but his turn toward racist ideology taints his legacy; it just goes to show that even brilliant scientists have dark corners in their minds.

The charges of racism concern statements Watson made about biological differences between populations, such as this one: “There is no firm reason to anticipate that the intellectual capacities of peoples geographically separated in their evolution should prove to have evolved identically,” he wrote. “Our wanting to reserve equal powers of reason as some universal heritage of humanity will not be enough to make it so.”

None of the postmortems questioned whether these views were actually racist. That part was assumed. The Atlantic, Nov. 10: “Watson was notorious for his bigotry.” The Guardian, Nov. 7: “Nobel prize winner shaped medicine, crimefighting and genealogy, but later years marred by racist remarks.” Le Monde, Nov. 7: “The Nobel Prize-winning biologist who helped discover the double-helix structure of DNA later faced global condemnation for racist comments about Black intelligence.” The Independent, Nov. 7: “Watson’s later years were marred by widespread condemnation following racist remarks, including assertions about the intelligence of Black people.” Science, Nov. 9: “How do you view his racist assertions about Black people having lower average IQ scores than white people because of genetics?”

A very different political lens distorted the investigations and conclusions of European anthropologists, leading to racial taxonomies that seem almost laughable in their hubris.

Somewhere along the way, the scientific and lay community decided that mere speculation about group differences in brain function and cognitive ability signals bigotry. The experts have spoken: any suggestion of cognitive differences between populations is pseudoscience or, worse, scientific racism. Society cannot allow such statements to stand.

The political fashions of the time dictate what researchers can study, how they can study it, and how they can interpret the results. A couple of hundred years ago, a very different political lens distorted the investigations and conclusions of European anthropologists, leading to racial taxonomies that seem almost laughable in their hubris. After World War II, the political winds reversed course—quite understandably—leading to a visceral recoil from any research that touched on group differences. The rise of DEI cemented this stance.

I won’t comment on the evidence for or against Watson’s alleged racism—it’s not the point of this essay and no one knows what is truly in someone else’s mind. What concerns us here is whether holding, expressing, and studying some such ideas is inherently racist.

In 1975, after campus protests at Yale University disrupted speeches and other events, the university commissioned an inquiry, chaired by the renowned historian C. Vann Woodward, to re-evaluate its stance on free speech and dissent. This culminated in the Woodward Report, which staunchly took the side of free inquiry: “The history of intellectual growth and discovery clearly demonstrates the need for unfettered freedom, the right to think the unthinkable, discuss the unmentionable, and challenge the unchallengeable.”

Fifty years after that commission, we’ve made breathtaking progress… in the opposite direction. Can you imagine “discussing the unmentionable” at a faculty meeting at Yale or Brown? In Scientific American or Nature Human Behaviour? The heady winds of free inquiry have crashed into the unyielding thicket of emotional safety and victimhood, losing all their force. Certain topics have gotten buried in the rubble, never to be unearthed.

Let us turn to a very similar don’t-go-there topic: the contention that men have some innate cognitive advantages over women. Many large-scale studies have found that men do better than women in spatial awareness and in mathematics. The fact that I—a woman—outperform most men in math and can always point North does not detract from these statistical trends. Nor does it reflect on the research showing that women outperform men in verbal fluency and reading comprehension, fine motor skills, perceptual speed, verbal memory, retrieving information from long-term memory, and multitasking. (Here again, I’m a terrible multitasker, but the trend prevails.)

If I had to bet my life on it, I would wager that genes have something to do with it. This belief doesn’t upset my sense of justice or worth, as I view it in morally neutral terms: evolution likely pushed male brain architecture in certain directions because men needed to hunt and keep families alive in unforgiving environments, and it pushed female brain architecture in other directions for equally adaptive reasons. There’s no honor—or dishonor—in getting a push from evolution. It’s just what nature (may have) served up to keep the human species thriving.

Curiously enough, society feels free to posit that biology gives men a greater inclination than women toward aggression. But if you suggest that biology could also nudge the sexes along different cognitive paths, you’re an instant pariah. Why the double standard? As best I can figure, it’s because of an irrational belief that good things (such as intelligence) have to be distributed evenly, while bad things (such as aggression) do not.

What Watson was suggesting is that nature doesn’t always distribute good things evenly. His belief that certain populations may have cognitive advantages—while contested by many—does not constitute racism, if one defines racism as the systematic devaluation of a group of people.

If you believe that people should not express such thoughts or conduct such research because of its potential for social harm, then say so. It’s a legitimate position to hold.

Crying “racism” to silence a line of inquiry we don’t like is disingenuous and intellectually lazy. Biologist Jason Malloy called out this sleight of hand in 2008, in an editorial for Medical Hypotheses. Speaking of attacks on Watson’s moral character, he wrote: “The media and the larger scientific community punished Dr. Watson for violating a social and political taboo, but fashioned their case to the public in terms of scientific ethics.”

Some of us are afraid to say what we really think, though once in a while we push ourselves to do it. Others are less afraid, for various reasons. J.K. Rowling has F— You money. Dave Chappelle has F— You skin color. Watson, arguably, had a F— You reputation in science. He used it to discuss the unmentionable, as befits a true scientist.

If you believe that people should not express such thoughts or conduct such research because of its potential for social harm, then say so. It’s a legitimate position to hold. But don’t dress it up as case-closed science. Science is never case-closed, especially when an entire line of research has been pronounced off-limits.

For all his faults, not least a perverse delight in shocking people, Jim Watson was a brilliant scientist.

— Richard Dawkins (@RichardDawkins) November 8, 2025

How can one generate evidence in either direction when forbidden to pursue it?

James Watson may well have been a racist. Some of his comments betray a callous elitism and, well, simple bad taste. About maintaining human brain power in the future: “If there is any correlation between success and genes, IQ will fall if the successful people don’t have children.” About women in science: “I think having all these women around makes it more fun for the men but they’re probably less effective.”

Ugh.

But if he was a racist, it’s not because of his speculations about innate differences between groups. We owe him this concession.