When AI Thinks for Us

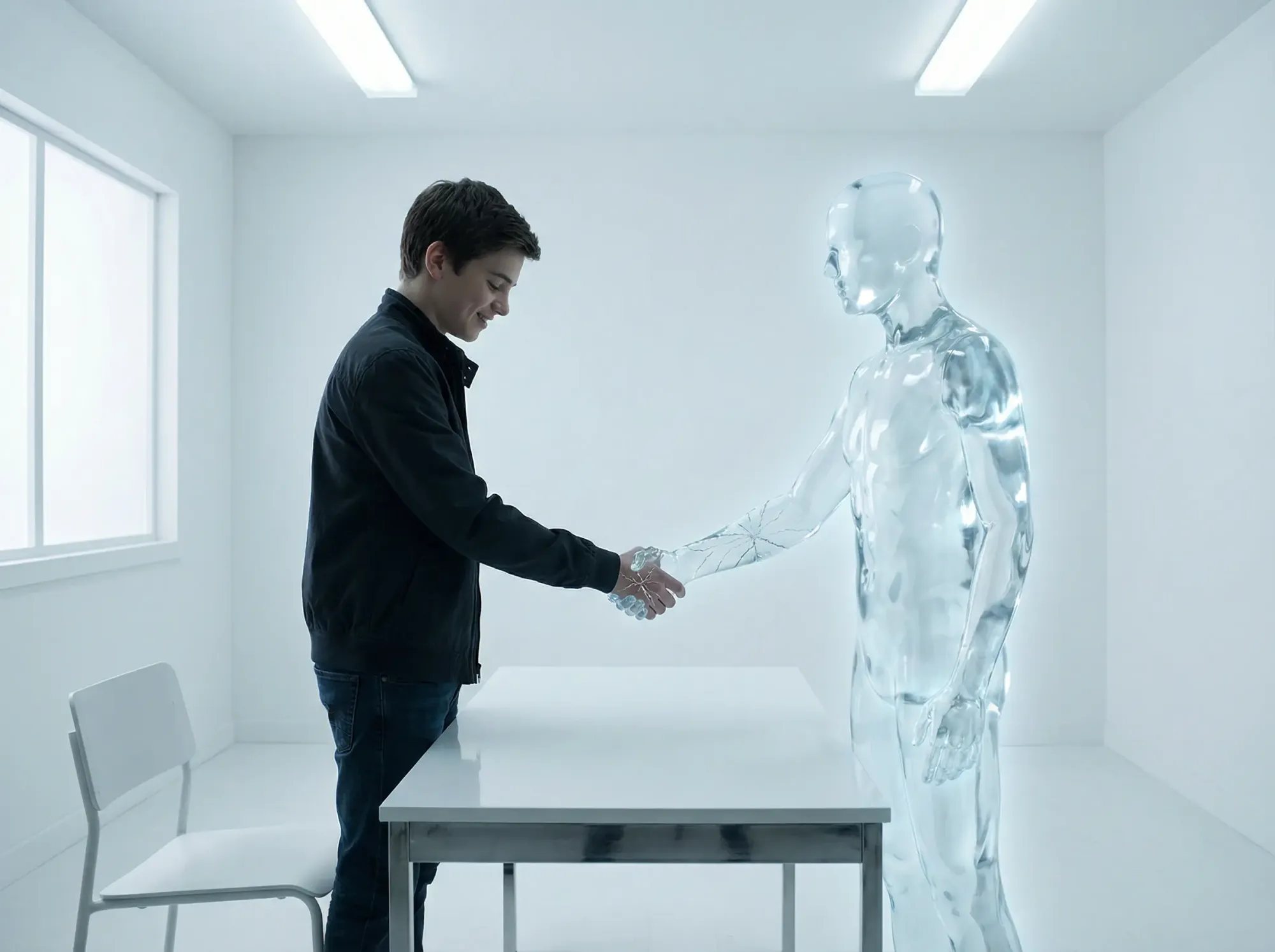

In modern education, Artificial Intelligence is increasingly marketed as a cognitive prosthesis: a tool that extends our mental reach, automates drudgery, and supposedly frees us to focus on higher-order creativity and insight. According to this narrative, AI does not replace thinking—it liberates it.

But beneath the polished interface of today’s Large Language Models (LLMs) lies a neurological and ethical trap, one with especially serious implications for developing minds. We are witnessing a subtle but profound shift from using tools to thinking with them, and, increasingly, letting them think for us.

The question Skeptic readers should be asking is not whether AI is impressive—it clearly is—but what kind of minds are formed when different kinds of thinking become optional. One place where this shift is especially revealing and especially consequential is moral development.

Moral Development

In moral education, how one arrives at a judgment matters more than which judgment one reaches. It is not about acquiring correct answers. Moral development involves cultivating the capacity to deliberate, restrain impulse, tolerate ambiguity, and reflect before acting. These capacities do not emerge automatically, rather, they are trained through effortful use. AI, however, is mostly indifferent to process and optimizes for output.

When we outsource the labor of reflection to an algorithm, we risk a form of ethical atrophy. This is not a Luddite rejection of AI but a skeptical, evidence-based examination of benefit claims that rarely account for developmental cost.

These are not merely philosophical concerns. They are grounded in the biology of how our moral capacities arise. To understand the stakes, we must begin with the adolescent brain. The teenage brain is not a finished system but more like a construction site. The prefrontal cortex (the executive center responsible for impulse control, long-term planning, and moral deliberation) undergoes rapid, uneven development throughout adolescence. Neural circuits that are exercised are strengthened and stabilized; those that are neglected are pruned away. This is not metaphor. It is biology.

Moral development involves cultivating the capacity to deliberate, restrain impulse, tolerate ambiguity, and reflect before acting.

Moral development, as I explain in my book AI Ethics, Neuroscience, and Education, depends on what researchers call cognitive friction. This friction appears as hesitation before a difficult choice, the effort of weighing competing values, and the discomfort of uncertainty. These moments feel inefficient, but they are also indispensable. Generative AI, by design, removes this friction.

When a student asks ChatGPT for a nuanced ethical argument and receives an instant, polished response, the brain skips the work. The student receives the answer without undergoing the cognitive struggle required to produce it. Ethical questions begin to resemble technical problems with downloadable solutions. Students lose the habit of lingering in uncertainty; the very space where moral reasoning takes shape. AI does not hesitate and generates outputs based on probability, not conscience. Humans, however, should hesitate. That hesitation is not weakness but moral functioning.

Cognitive and Emotional Development

If moral reasoning is one casualty of reliance on LLMs, it is far from the only one. Consider writing. Writing is not simply a way to display what we know—it is the process through which we figure out what we think. Organizing vague intuitions into a coherent argument places a heavy demand on the developing prefrontal cortex, and when AI performs this structuring, it deprives the brain of precisely the exercise it needs to mature.

When we outsource the labor of reflection to an algorithm, we risk a form of ethical atrophy.

If intelligence is measured only by output, for example the finished essay or the correct solution, AI appears miraculous. But if intelligence is understood as the capacity to reason, deliberate, and restrain impulse, AI-driven cognitive offloading begins to resemble a neurological shortcut with long-term consequences, not unlike actual shortcuts that reshape the terrain.

The danger does not stop at cognition. It extends into emotional and social development. We are entering an era of affective computing, in which machines are designed not merely to process information but to simulate emotional responsiveness. AI systems now speak in tones of empathy, reassurance, and concern. They never interrupt, misunderstand, or demand reciprocity.

For an isolated or anxious adolescent, an AI companion can feel safer than unpredictable human relationships. It offers validation without vulnerability and empathy without risk.

When a student asks ChatGPT for a nuanced ethical argument and receives an instant, polished response, the brain skips the work.

But moral growth, just like cognitive abilities, does not occur in comfort. Human relationships require patience, accountability, and recognition of another person’s interior life. They involve misunderstanding, disagreement, and the difficult work of repair. AI relationships require none of this. They are emotionally efficient, and ethically hollow.

What they provide is a psychological sugar rush: immediate affirmation without the nutritional value of genuine connection. The ethical danger here is subtle: We are not merely giving students a new tool but also shaping their preferences. We are quietly training young people to prefer relationships that never challenge them. Over time, this fosters comfort with anthropomorphic simulations and anxiety toward real human empathy, which is messy, incomplete, and demanding.

Toward Skeptical AI Literacy

This is not a call to ban AI. The question is not whether we use AI in education, but how and when.

Beyond the developmental effects described here, we should also note that LLMs hallucinate. With remarkable confidence, they fabricate sources, misstate facts, and invent details. This fluency creates trust. What emerges is a form of passive knowing: information is consumed without ownership or justification. In an era where machines can generate infinite content, the ability to distinguish truth from fluent fiction becomes one of the most critical civic skills we have. Ironically, our increasing reliance on AI may be eroding the vigilance that skill requires.

We are quietly training young people to prefer relationships that never challenge them.

This means we need to be teaching students both how to prompt machines and how to resist them. In other words, AI output should be treated not as a truth to be consumed but as a hypothesis to be tested. We also need to teach the value of the seeming inefficiency of human thinking.

Finally, the central ethical question of our time is not whether machines can think for us. It is whether in allowing them to do so too often we risk forgetting how to think for ourselves. We must be careful not to engineer the atrophy of human wisdom.