Why Are Hollywood’s Bad Boys & Babes Always the Best Dressed?

Growing up in the 50s, most boys wanted to be the hero—the square-jawed savior rescuing the damsel in distress. Not me. Whether it was my already skeptical personality or my growing up in a mob town in Jersey, I gravitated toward the villains. They were cooler, sharper, and far more interesting than the bland do-gooders they faced.

Take Flash Gordon, for example. While other kids idolized Flash, I looked up to the Emperor Ming and looked a lot at his dark-haired, sharp-witted Princess Aura. She often saved Flash—ungrateful bastard that he was—rather than the other way around. Even in high school, when studying Shakespeare, I’d much rather read the lines of the villainous Richard III or the irreverent Mercutio than the naïve, love-struck Romeo or even the heroic Henry V.

Villains had panache; heroes just seemed dull.

As I grew older, my admiration for antiheroes deepened. From Doc Holliday’s cool detachment to James Mason’s enigmatic Captain Nemo, these characters defied convention. They were flawed but fascinating, capable of both cruelty and brilliance. Their complexity made them unforgettable.

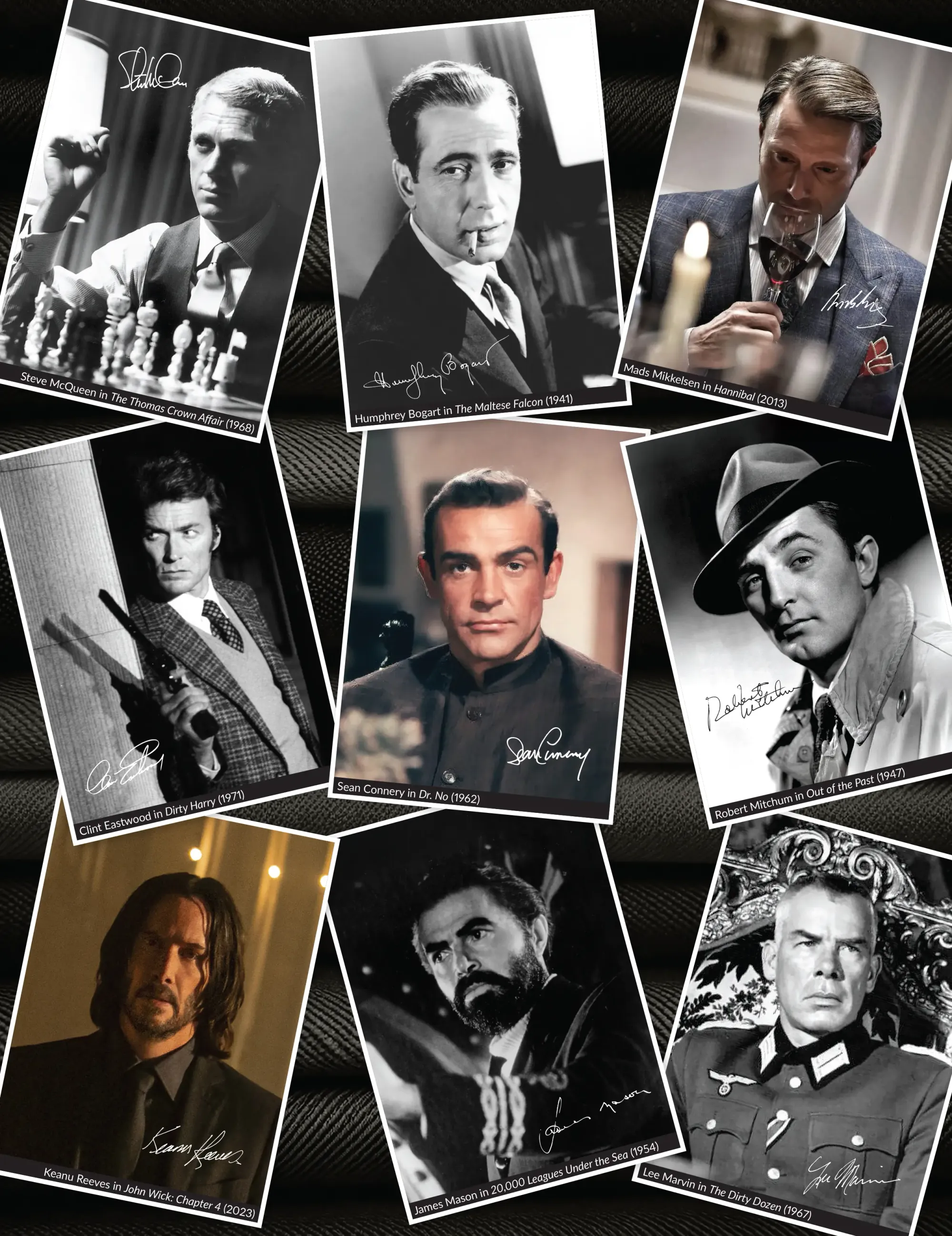

Indeed, most cinematic heroes have proven so dull—both sartorially and psychologically—and out of touch with increasingly cynical times that antiheroes have often stolen the spotlight, whether intentionally or not. Think Bogart’s Sam Spade, just about every Bob Mitchum character, Steve McQueen, Lee Marvin, and Clint Eastwood, whether as the “Man with No Name” (with Lee Van Cleef’s Col. Douglas Mortimer as a darkly cool supporting antihero) or “Dirty Harry” Callahan. Add to the list James Bond in his many incarnations and, more recently, Keanu Reeves’s John Wick—four times over. These cynics, with their sharp skepticism, exude competence, class, and above all, cool. Far from Homecoming Day heroes, they embody the invented pop-psychology “Sigma Male” archetype—if it were ever real to begin with. And made up it was.

There’s no solid psychometric research supporting the concept of the sigma male or any other pop personality types. Ironically, in an age where stereotyping individuals by group affiliation is taboo, countless schemes have emerged to pigeonhole people into fabricated personality categories. Tests like the Enneagram, the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), its derivative 16 Personalities Test, the DISC profile, the Hire for Success Test, or even the Four Seasons Color Analysis are just a click away. Yet, none demonstrates reliability or validity. True psychometric tests measure continuous traits, not fixed types—making those faddish pop schemes no more credible than the ancient four humors of sanguine, choleric, phlegmatic, and melancholic. Like the late Amazing Randi’s debunking of astrological signs, these types appeal by offering something relatable for everyone. Why the fascination? Because nothing terrifies most individuals more—more than a check engine light or a certified letter from the IRS—than facing the daunting task of simply being themselves.

Some might argue that antiheroes trace their roots back to Odysseus, history and mythology’s hero—or war criminal, depending on whether one sides with the Greeks or with the Trojans and their (self-proclaimed) Roman descendants. While noble Hector, Alpha male Achilles, and leading man Paris meet their ends on the plains of Troy, wily Odysseus survives. Master of trickery and deceit, he makes it back to Ithaca—but only after a ten-year odyssey filled with lies, schemes, and betrayals against men, women, gods, goddesses, and monsters alike. (And man, he done that Cyclops dirty!)

What about the bad girls?

Bad girls got their start back in Greek mythology with Medea, or with Jezebel and Delilah if you prefer Hebrew mythology. Or could it have been way, way back there when Eve tempted Adam with that Forbidden Fruit in the Garden of Eden, thereby causing no less than the Fall of Man, and thereby leaving all their descendants tainted by Original Sin. Now consider that according to certain British Israelism or Christian Identity readings of Scripture, Eve was tempted not to partake of some actual piece of proscribed produce but to get up close and personal with the very Devil in the Flesh, and that she then seduced Adam into some gay-straight Satanic threesome, thereby conceiving—literally conceiving—half-brother fraternal twins good guy Abel and bad boy Cain, and by so doing spawning both the righteous ten tribes of Israel, Children of God (that is, European, White, especially Anglo-Saxon, peoples) and the evil Serpent Seed of Satan (Jews). Quite a hermeneutical stretch, but there are those who ardently believe it.

Between Homeric Patriarchal times and our own, the Bard would give us both the juiciest female dramatic part ever written in Lady Macbeth, and the bloodiest in Tamara, Queen of the Goths (Rome’s real barbarian foes by that name, not today’s subculture) in Titus Andronicus. Then centuries later, dark dames—definitely no damsels—would take over the silver screen as the femme fatales who populated noir cinema of the late 40s and early 50s, only to give way to the typical 50s helpless heroines, but then to re-emerge starting in the more cynical 60s.

Noir Femme Fatales are the ultimate roles that embody the kind of woman a man would die for (and often does).

The roster of noir distaff dramatis personae includes the most impactful and complex female characters and performances in filmdom. These are powerful, ambitious, manipulative, and unashamedly very sexy women, who shatter traditional female stereotypes, never playing second fiddle to their male lead.

Why do they resonate? Because villains have the depth needed to drive the drama. And let’s face it—being good is dramatically boring. Stick to the straight and narrow, keep your nose clean, and to the grindstone—it’s the recipe for trite, feel-good drivel.

Noir Femme Fatales are the ultimate roles that embody the kind of woman a man would die for (and often does). Some of the best examples of these dangerous, irresistible dames include Marlene Dietrich in The Blue Angel, Mary Astor in The Maltese Falcon, Gene Tierney in Laura, Veronica Lake in This Gun for Hire, Barbara Stanwyck in Double Indemnity, Lauren Bacall in nearly anything opposite Humphrey Bogart, Joan Crawford in Mildred Pierce, Rita Hayworth in Gilda, Lana Turner in The Postman Always Rings Twice, Ava Gardner in The Killers, and even Marilyn Monroe in The Asphalt Jungle. Interestingly, in 1946’s The Dark Corner, Lucille Ball and William Bendix starred as noir leads, only to later become the wholesome, goofy characters of I Love Lucy and The Life of Riley, respectively, in the 50s. Both had other notable noir roles, with Lucy even playing a comic gangster’s moll in the 1934 short Three Little Pigskins alongside The Three Stooges.

For a beautifully illustrated catalog of film noir femme fatales, their faces, and their fashion, check out Kimberly Truhler’s Film Noir Style (GoodKnight Books, 2020). Just remember to keep your eye on them—in both senses of the word.

Dressed to Kill

The femmes fatales of film noir donned a diverse wardrobe, but the common thread was that every piece served a purpose. Whether dressed to convey innocence, temptation, vulnerability, or power, whatever a noir woman wore, she wore it to advance her purposes. Noir females even dressed to kill—often literally. Both the storyline and the performance lead you into believing that the character herself is selecting her wardrobe rather than the studio, the director, or, however indirectly, the audience.

With vision being the predominant sense for Homo sapiens, the influence of fashion and style permeates nearly every aspect of human life. So, what then are the common threads running through villainous attire—not only around the world but across the ages? Therein hang not only their sartorial threads, but several tales.

This is—or likes to think of itself as—the Age of Everyman, Everywoman, and Everyperson. We worship—or at least publicly venerate—the Great God of Equality. Yet, while no one but a villain or villainess dares to be labeled an elitist, we all want to feel “special,” at least in the eyes of someone else. Equality may be sacred, but the fundamental law of life is diversity. No two individuals are identical in body or behavior—not even identical twins brought up in the same household. And though diversity is another cherished ideal of our time, logically, it cannot coexist seamlessly with absolute equality. Add liberty into the mix, and you’re left trying to balance on a three-legged stool, each leg pointing in a different direction: up, down, or sideways.

While heroes and heroines are designed to appear and act as everyman or everywoman … villains exude qualities that set them unmistakably apart.

The villains and villainesses of page, stage, and screen—whether big or small—don’t just reject equality; they revel in their self-assumed superiority. They demand to be treated as not only above those around them, but above the rest of humanity. This conceit is flaunted in their attire, speech, and mannerisms, broadcasting their dominance to all. They possess the power, wealth, and time to curate the finest wardrobe, complete with servants to dress them and maintain their clothing.

While heroes and heroines are designed to appear and act as everyman or everywoman, allowing readers or viewers to quickly and easily identify with them, villains exude qualities that set them unmistakably apart. Everything they do—every gesture, choice, and word—displays wealth, power, discipline, dominance, sophistication, elitism, and, above all, control, elevating them far above the crowd.

Can we imagine an iconic villain or villainess who isn’t intelligent, powerful, articulate, and impeccably dressed? Of course not.

While, as Jesus noted, good, honest, reasonable, and ordinary people are “the salt of the earth” (Mark 9:50), they rarely drive significant change. Five centuries earlier, Heraclitus framed his worldview around a stark truth: war and struggle are the father of all, the creative forces that disrupt and transform, from upsetting apple carts to uprooting the Garden of Eden. Such upheaval requires agency, power, wealth, intellect, status, and, above all, the will to wield them, regardless of the costs inflicted on others. A weak-willed, poor, or dim-witted malefactor isn’t a villain—they’re just a lout. High drama demands more than foiling the clumsy schemes of a stumblebum or a bimbo; such simple characters simply lack the mental capacity needed to machinate. If Mephistopheles were a fool, there’d be no Doctor Faustus—just Father Knows Best. Can we imagine an iconic villain or villainess who isn’t intelligent, powerful, articulate, and impeccably dressed? Of course not. These are the very attributes that define and identify them.

Exhibit A: Dr. Hannibal Lecter, the refined, educated, and methodical serial killer who moonlights as a gourmet chef and cannibal, stands as the epitome of sophistication in villainy. Whether portrayed by Anthony Hopkins on the big screen or Mads Mikkelsen on the small, Lecter exudes an air of cultured menace. Hopkins employs an upscale “Mid-Atlantic” intonation, while Mikkelsen’s accent leans “continental,” but neither voice bears the faintest resemblance to Joe—or Flo—from Kokomo. This distinction is further highlighted by their verbal foils: FBI Agents Clarice Starling, with her “white trash, trailer park, tornado-bait” twang, and Will Graham, whose accent matches his “boat motor-fixing” sideline.

Exhibit B: Contrast Lecter’s urbane menace with the stark realism of Henry, the titular bloodthirsty berserker in Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, played by Alabama-born Michael Rooker. Henry is a psychopathic drifter who slashes his way across America’s low-rent backroads. While Lecter indulges in fava beans and a nice chi-AN-ti, donning meticulously tailored ensembles, Henry wolfs down junk food, washes it down with beer, and slouches around in blue jeans and a “wife-beater” undershirt.

The villains and villainesses of page, stage, and screen don’t just reject equality; they revel in their self-assumed superiority.

The cultural impact of these two figures couldn’t be more divergent. Hannibal Lecter has garnered multiple Academy Awards, spawned sequels, prequels, books, films, and TV series, and captured vast audiences. At one point, a sequel even places him under an alias as a curator at Florence’s Renaissance Palazzo Caponi. In contrast, Henry remains an underground cult classic, his lone sequel depicting him as a homeless drifter who eventually lands a crappy job at a port-o-john company. Hannibal Lecter has been crowned the #1 Screen Villain of All Time, while Henry languishes as a brutal figure on the fringes of pop culture. Even the most ardent advocates of justice for the underprivileged, like the ACLU or the Innocence Project, might hesitate before taking on Henry as a client.

Uniformly Bad?

The ultimate villain collective archetypes in Hollywood are the Romans and the Nazis. Both are consistently depicted as epitomizing sharpness in uniform, cultured sophistication, physical fitness, and iron discipline. They are portrayed as ready, willing, and able to fight ruthlessly, all the while exuding an air of elitist superiority and blatant disregard, if not contempt, for others.

Notably, these groups serve as universal antagonists, with no one in filmdom rushing to defend their deeds or ideologies. That said, Monty Python’s Life of Brian does acknowledge the Romans’ contributions—albeit through the lens of satire—by listing their undeniable achievements of: “sanitation, medicine, education, wine, public order, irrigation, roads, the fresh-water systems, and public health.”

But back to those uniforms. It’s a common misconception that Hugo Boss designed the SS uniforms. In reality, the uniforms were designed by two SS officers, while Boss’s firm merely produced them—albeit using forced labor in the process. However, Hugo Boss was far from the only fashion house to “go along to get along” under the Third Reich. Across the border in Vichy France, the storied houses of Chanel and Dior also operated in ways that raise questions about their wartime practices, suggesting their legacies weren’t entirely free of compromise either.

No matter how enjoyable it is to watch these bad boys and babes … there’s no way in hell we’d want them in charge of our own real lives.

Authoritative-looking uniforms do seem to be a hallmark of authoritarian systems, designed to inspire obedience among members and instill fear or intimidation among outsiders. Historically, dictatorships have often showcased a proliferation of uniforms, along with banners, symbols, and insignias, as visual reinforcement of hierarchy and power. From Mussolini’s Italy to Hitler’s Third Reich, Stalin’s Soviet Union, and Kim’s North Korea, uniforms have served as both a unifying and a polarizing force.

These regimes introduced a spectrum of identifiable uniforms: Black Shirts, Brown Shirts, Red Shirts, Green Shirts—each color-coded to signify allegiance and role within the totalitarian state apparatus. Uniforms weren’t limited to the military or police; they extended to government officials, party members, and especially those who served or represented the Leader directly. Their uniforms thus became not just clothing, but symbols of loyalty, order, and, above all, control.

In liberal free market democracies, you wouldn’t expect to see the same proliferation of uniforms as seen in authoritarian regimes. But, hold on a second—turns out we’re surrounded by uniforms everywhere we go, not from the government, but from private corporations. Whether it’s fast food chains, convenience stores, big box retailers, pet shops, banks, and health clubs, or even girl scouts going door-to-door selling cookies, uniforms are all around us. They aren’t projecting government authority or power, but instead the customer-centric vibe of businesses vying to sell us the goods and services we desire.

It’s not der Führer, Il Duce, or Comrade Chairman that’s always right, but you and me—the customer. It’s not the hard commands of government authority here, but the consumer-friendly soft sell of businesses competing in the marketplace for our attention and our money.

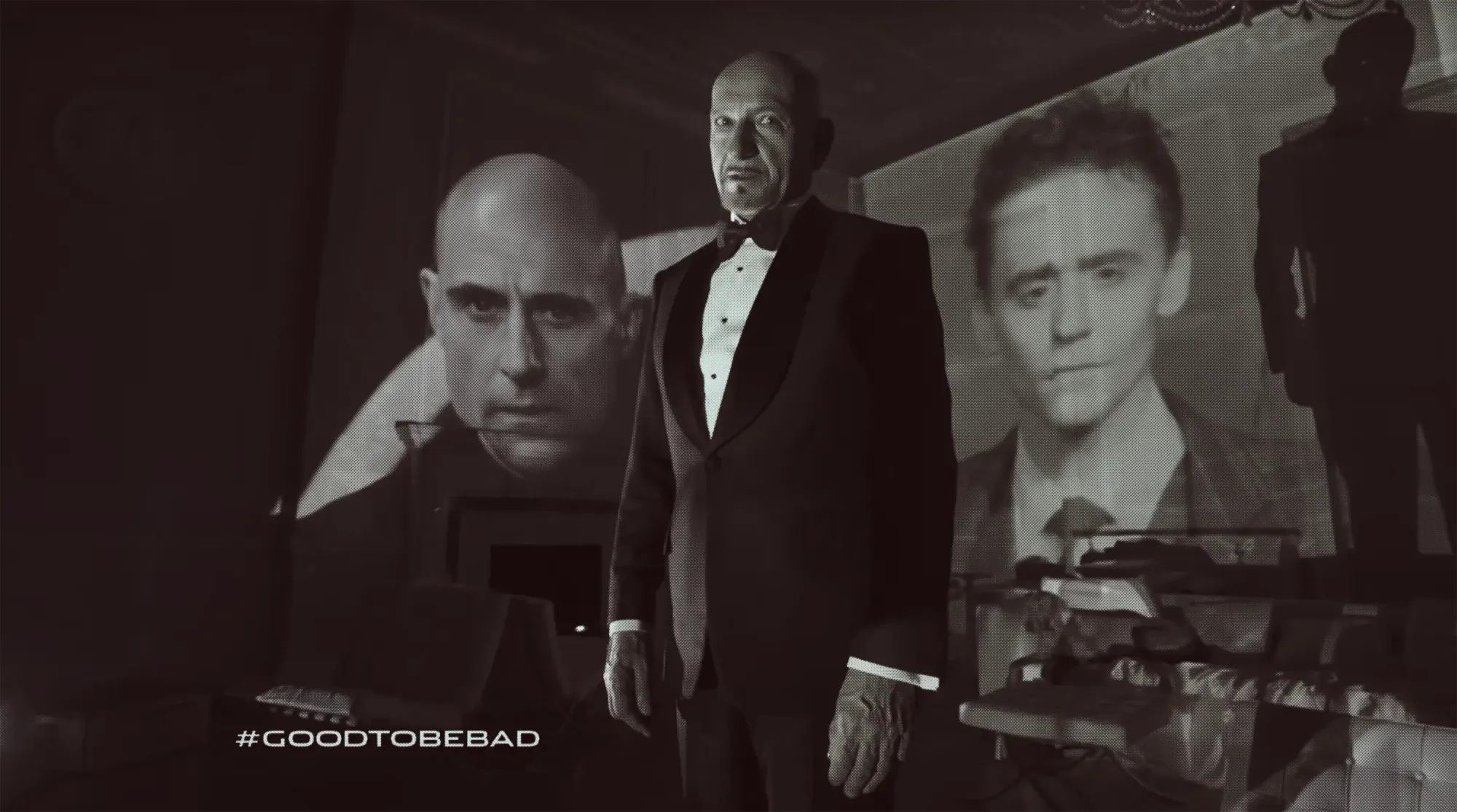

Back to Ben

It’s certainly been “good to be bad” for Sir Ben Kingsley and the many other talented actors and actresses who have earned honors, fame, awards, and fortune portraying iconic villains and villainesses on stage, screen, and even in commercials. No matter how enjoyable it is to watch these bad boys and babes who are always impeccably dressed and eloquently well-spoken, there’s no way in hell we’d want them in charge of our own real lives.