Why Health Journalism Feels So Misleading

If you scroll through the news today, it’s easy to feel like every health headline is expertly designed to scare you. Whether it’s because journalists are playing a game of telephone by lazily regurgitating exaggerated press releases without consulting the actual studies they report on, deliberately oversimplifying or distorting findings, or even politicizing the issues—we’re very often not getting an accurate perspective. And social media tends to further amplify this problem.

Take, for example, recent coverage of plant-based meats and heart disease. Headlines claimed these products were a cardiovascular risk, based on a study from the University of São Paulo and Imperial College London. In reality, the study primarily attributed cardiovascular risk to ultra-processed foods like pre-packaged breads, pastries, and cookies, not plant-based meat alternatives, which constituted only 0.2 percent of the participants’ diet. But the headlines claimed otherwise.

Or consider a New England Journal of Medicine study on structured exercise and colon cancer recovery. Headlines proclaimed exercise to be superior to medication. But the study never compared exercise directly against drugs; all participants had already received chemotherapy.

The truth is, science is complex, and we live in an environment where many believe that the experts who should be equipped to understand it aren’t to be trusted.

Even marketing campaigns can mislead. A Scottish tanning salon chain, Indigo Sun, ran an ad claiming moderate sunbed use reduces deaths from cancer and heart disease, citing a University of Edinburgh study. But the research was taken out of context—the original study didn’t focus solely on sunbed use and omitted serious health risks like increased melanoma.

The truth is, science is complex, and we live in an environment where many believe that the experts who should be equipped to understand it aren’t to be trusted. Many of us subscribe to the illusion that we can get just as good a handle with a few Google searches or AI queries as the researcher who had spent the last 20 years of their life studying a single protein. Poet Alexander Pope put it well: “A little learning is a dangerous thing.” Meanwhile, some who distrust “establishment” experts will follow those they do deem worthy—TV doctors, online influencers, or the RFK Jr.’s of the world.

Jessica Plonchak, Executive Clinical Director at Choice Point Health, a certified outpatient addiction and mental health treatment center based in New Jersey, has over a decade of experience in addiction recovery, mental health, and integrated care. She told me one of the most common claims she sees online is that a short “dopamine detox” or “digital fast” can “reset” your brain and regulate dopamine levels in just a few days. “This is completely scientifically incorrect,” she said. “You cannot reset such a complex neurochemical system in a few days or over the weekend. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that your brain produces consistently. While short breaks from screens or highly rewarding activities can be emotionally beneficial, calling them a ‘dopamine reset’ is not factual.”

Plonchak emphasized that real change comes from sustained, structured habit modifications, not weekend cleanses. She also offered a few practical tips: be skeptical of buzzwords like “reset,” “hack,” or “detox”; check whether claims are supported by expert consensus or peer-reviewed research; and look for neutral, authoritative sources like Harvard Health or Cleveland Clinic before jumping on a trend.

We need true experts to help make sense of the world. Dr. Liza Lockwood explains to me: “Nobody has time, or should they have, to do all the reading.” Lockwood is an emergency medicine physician trained at Washington University in St. Louis with a medical toxicology fellowship at NYU, spent years in academic medicine, global health initiatives, and even served as the snake bite doctor for the St. Louis Zoo. She is currently Medical Affairs Lead for the Crop Science division at Bayer. She’s no stranger to medicine, nor science communication.

We need true experts to help make sense of the world.

Even many doctors rely on guidelines and expert consensus because they can’t review all the evidence themselves, she notes. But when the “order of trust” breaks down, public confidence suffers. “It can be really damaging to have us lose trust in other domains where we should be able to trust the experts,” she warns.

But who, exactly, is deemed an “expert” for media commentary? Are most journalists even qualified to make that determination accurately? Indeed, who gets selected is not always the most experienced or knowledgeable expert—it might be someone a PR agency is pitching, or someone with existing media connections and savvy—chosen more for their ability to speak than analyze. And at times, it so happens that experts weighing in are doing so outside their field entirely.

Lockwood thinks that part of the problem is that there’s not a sufficient interest in science. “It’s kind of thought of as boring,” she tells me, “And there are not a lot of people out there that are good at explaining science.” She says this leaves the public with two extremes: corporate PR (“Trust us. It’s fine.”) or dense academic papers that most people can’t understand.

Scientific journals have issues beyond jargon. Many are behind very expensive paywalls where a single article costs as much as $50, making it hard for journalists or laypeople to read the original papers and verify claims—leaving them almost entirely dependent on press releases and media summaries. For that reason, quite often a single news article covering a study becomes the source for hundreds of follow-up stories, rather than the original research itself—a practice that’s been referred to as “churnalism.”

For example, a press release based on a study in New England Journal of Medicine claimed that a “historic discovery” was made linking birth defects to niacin deficiency. This resulted in many news stories about how vegemite can prevent miscarriages, often using verbiage from the press release word-for-word, and most significantly, leaving out that the experiments were mostly conducted on a mouse model. Reporters either used the press release as their source, or other publications reporting on that same release.

Meanwhile, sensationalized headlines proliferate, and readers often only retain the takeaway from the headline. There’s also a tendency to spread fear too broadly—or conversely, presumably to remain politically correct, avoid naming which groups are most at risk (as, most recently, with monkeypox). This leaves the public either terrified or uninformed. Editors also often avoid controversial but important stories because they fear staff revolt or activist pressure. According to a global survey of over 740 reporters and editors, nearly 40 percent of journalists covering climate issues had received threats, with 11 percent experiencing physical violence—leading to self-censorship. During the height of the pandemic, many major media outlets dismissed the possibility that COVID-19 originated from a lab leak, labeling it a conspiracy theory, in part due to concerns around xenophobia. Similarly, coverage around natural immunity was limited due to concerns around discouraging vaccinations.

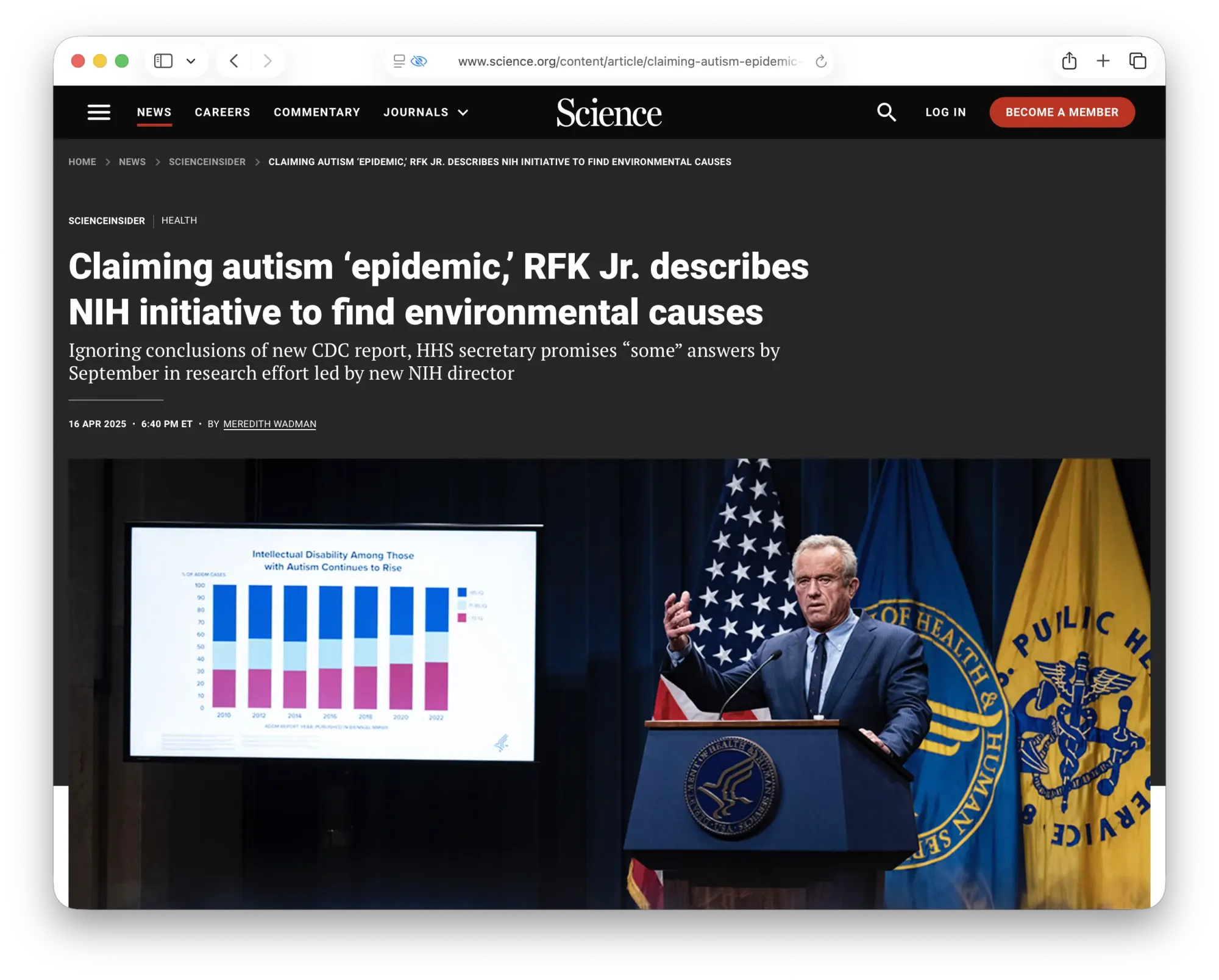

In light of Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s most recent statements, such as his promise that the NIH would find some environmental causes of autism, weakened COVID shot recommendations, and the CDC’s advisory panel recommending against MMRV shots for young children, Lockwood criticizes RFK Jr.’s recent pivot to blaming autism on Tylenol use during pregnancy, citing a weak, observational study that was rejected in court but still published and widely covered. Lockwood stresses that this is a classic example of association being misrepresented as causation—and of the media amplifying a claim without sufficient skepticism (PBS, for its part, published a debunking analysis).

Lockwood also shared with me the basis for some of RFK Jr’s vaccine skepticism and activism, namely the modern anti-vaccine movement that can be traced back to Andrew Wakefield, a British pediatric gastroenterologist who, in 1998, published a study in The Lancet involving just 12 children. The study claimed to show that children who had received the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine had developed both autism and gastrointestinal inflammation. Following the publication, Wakefield went to the media and publicly asserted that his research indicated a potential link between the MMR vaccine and autism, sparking widespread fear among parents.

At the time, the full extent of Wakefield’s conflicts of interest was not known. Investigations later revealed that he had received over £450,000 from lawyers intending to sue vaccine manufacturers, and he had also filed a patent for a rival single-measles vaccine, giving him a direct financial incentive to undermine public confidence in the existing MMR vaccine.

Over the following years, investigative journalist Brian Deer, reporting for The Sunday Times, meticulously exposed serious ethical breaches and scientific misconduct in Wakefield’s work. Deer’s investigation found that Wakefield had manipulated or falsified data, including fabricating colonoscopy results, to support his hypothesis. In 2010, The Lancet fully retracted the paper, citing “fundamental flaws” and ethical violations. Wakefield was also stripped of his medical license in the UK.

Health reporting is supposed to help the public make sense of complex science, but when it fails, the consequences can literally be a matter of life and death.

This delay, however, allowed the false claim to spread globally, fueling the anti-vaccine movement. “You could still download it with no warning that it had been debunked,” says Lockwood. It took 12 years to retract it. Despite the retraction and overwhelming evidence against his claims, the study had already captured the public imagination and fueled a growing anti-vaccine movement, which continues to influence vaccine hesitancy and public health debates today.

Dr. Richard Horton, editor of the journal, later said that with hindsight that The Lancet should not have published the paper. “There were fatal conflicts of interest in this paper,” he stated, “In my view, if we had known the conflict of interest Dr. Wakefield had in this work I think that would have strongly affected the peer reviewers about the credibility of this work, and in my judgment it would have been rejected.” He also stated that he regrets “the adverse impact this paper has had.” But then added, in an observation surely faced by most scientific and medical journals: “Professionally, I don't regret it. The Lancet must raise new ideas.”

Like many critics, Lockwood sees systemic incentives for journals to publish splashy, positive findings—sometimes at the expense of rigor: “We know there’s a publication bias: negative studies, null results, they don’t get published. So what we see is a distorted picture of the evidence.” She also notes that journals’ prestige culture can discourage dissent or correction: “There’s a hierarchy—you publish in NEJM [New England Journal of Medicine] or Lancet or JAMA [Journal of the American Medical Association] and it’s like gospel. But those journals have gotten things very wrong before. And because of their prestige, nobody questions them until it’s too late.”

As for Wakefield, he later moved to Texas, worked in alternative medicine, and teamed up with RFK Jr. and Del Bigtree (CEO of the anti-vaccination group Informed Consent Action Network) to promote anti-vaccine messaging.

The problem is, for many of us, the mere suggestion that something might be dangerous can cause fear. And people will often act on that fear. It’s one thing if it merely changes your coffee consumption habits due to the suggestion that decaf coffee may be linked to cancer, but it’s much more serious if women become too afraid to use Tylenol to control their fever during pregnancy—endangering both the developing baby and themselves.

Effective science communication requires a careful balance between accuracy, accessibility, and trust-building.

Health reporting is supposed to help the public make sense of complex science, but when it fails, the consequences can literally be a matter of life and death. Effective science communication requires a careful balance between accuracy, accessibility, and trust-building—the latter of which has been particularly eroded by the events of the COVID-19 pandemic. When the evidence is clear, so should be the coverage. That’s how we gain back trust.