Why That 140-Year-Old Hairbrush Still Sells: Consumer Psychology and Mythmaking

It’s the most wonderful time of the year. Sure, there are all the twinkly lights on display and family dinners, but really, it’s all about the shopping. Isn’t it? After all, each year we spend thousands of dollars around this time (retail sales in the U.S. between Black Friday and Christmas will likely surpass $1 trillion for the first time this year, up from $994 billion in 2024)—and not all of it on gifts either. It’s the Super Bowl of consumerism.

It’s hard to resist. Every few minutes I’ll get some sort of notification of a once-a-year sale that I must take advantage of immediately. I’m being primed to want things that I never really even thought of because they happen to be 20 percent off. I get nagging follow-up messages to get the items I happened to have glanced at but didn’t succumb to—before it’s too late, before they are gone forever (or at least the discount is)! That’s the annual ritual.

Some, however, are more disciplined than I. They wait until this time of year to buy the things they actually want and need at a discount. They are the real unsung heroes of the season. Just the other day a woman in my writers’ group proudly showed off her new Apple Watch that she had waited all this time to get. “I got it for cheap,” she exclaimed proudly, “I don’t know if it’s any good.”

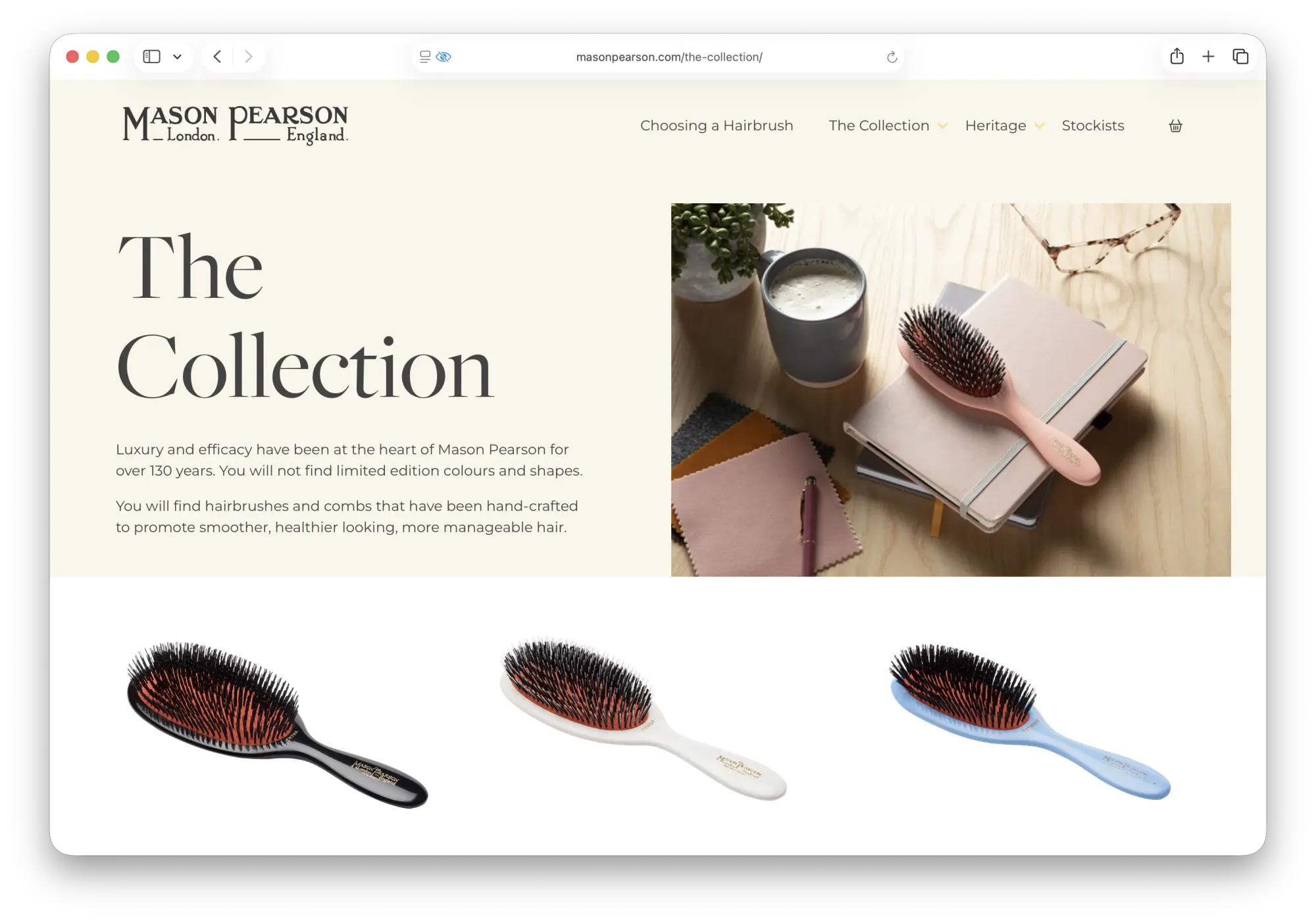

As for me, I’ve been eyeing a Mason Pearson brush for at least 15 years. Girl math dictates that had I bought it 10 years ago, I would have gotten it for half off. I’m told the quality is so good that it will last long enough to pass on to my children—because that’s what every child craves: a used hairbrush. Maybe in a few years, when it’s twice the price?

Mason Pearson, though, represents a “legacy” brand in an increasingly disposable world. It is characterized by its longevity (think: Levi’s and Tiffany & Co), rich history, perception of quality, and cultural relevance. Brands come and go, but Mason Pearson gets its name from its founder, an engineer who first created it in 1885. Multiple generations have enjoyed smooth hair from these high-quality durable brushes that continue to be handcrafted in England and are referred to as “the Ferrari of brushes.” It has cult status. I hear that spoilt pets like it too.

But this isn’t an ad for Mason Pearson. It’s a column about psychology.

Legacy brands tend to evoke nostalgia, one of the most powerful feelings a brand that wants to sell lots of products can invoke. It reminds us of simpler or happier times, or connects us to family members who might have used the same products. Or people like Marilyn Monroe, who to this day is still partially responsible for the sales of Erno Laszlo skincare products and Chanel No. 5 perfume. If you wear the latter to bed, you too can continue the legacy. This emotional resonance and sentimental bond help foster brand loyalty by transforming the product into something more meaningful.

As Mad Men’s Don Draper describes it, nostalgia is a “twinge in your heart, far more powerful than memory alone.”

The legacy brand also comes with a story.

Successful legacy brands leverage their rich history and craftsmanship through compelling storytelling. This narrative allows consumers to feel like they are part of an ongoing legacy, connecting them with tradition and artistry that defines the brand. A good example of this type of marketing is deployed by Grado Labs, a company that produces headphones “handmade in Brooklyn, producing the finest audio products since 1953 in the building that our father/grandfather/great grandfather Pasquale bought back in 1918.”

Indeed, research shows that our brains respond to stories, triggering the release of oxytocin, a hormone that happens to promote trust. This helps explain the results of the 2009 Significant Objects experiment conducted by Robert Walker and Joshua Glenn where they found that pairing a story with a product was able to increase its perceived value by up to 2,706 percent.

According to clinical psychologist Clary Tepper, when consumers buy into a brand they are engaging in what is deemed by psychologists to be “symbolic consumption” whereby the brand becomes a representative of a set of ideals or values.

“From a psychological point of view, the principles of memory, identity, and emotional security are all at work here,” she tells me, “For consumers who feel like the world is constantly changing, legacy brands offer a sense of stability and continuity. Those brands also tap into shared cultural history, collective memory, and identity, all of which can foster a sense of belonging and trust. If consumers have had positive experiences with these brands in the past, engaging with them again can activate reward pathways in the brain.”

Deidre Popovich, Associate Professor of Marketing at Texas Tech University, agrees: “People are quite drawn to legacy brands because they feel very familiar and comforting. From a consumer psychology perspective, these brands may be tied to early personal memories, such as thinking back to certain family routines when you were a kid. When someone sees a legacy brand, they often feel this sense of recognition that links back to earlier points in their life. That is what creates a feeling of nostalgia. It is usually less about the product itself or its functional purpose, and more about reconnecting with family moments and/or positive feelings.”

Ownership of a legacy brand’s products can also be a way for consumers to signal their aspirations or social status. It’s part of an identity that they can choose to put on—or change.

Sarah Seung-McFarland is a psychologist and founder of Trulery, where her focus is specifically on fashion and design psychology. She tells me: “In psychology, we know that consumers don’t just buy a product, they buy into the identity, lifestyle, and social meaning connected to it. Brands like Louis Vuitton have spent decades being linked to wealth, status, and an aspirational lifestyle through film, celebrity culture, and consistent visual storytelling.”

Brands, in a sense, become a stand-in for a world that might be within our reach. Though, says, Seung-McFarland, “For many, the desire came from the inaccessibility itself. Owning a legacy piece represented the version of themselves they hoped to become.”

It’s also a type of reassurance about the quality and reliability of the brand. Its longevity is a testimony to that. That’s why we’re seeing a bit of a revival towards appreciation for long-standing brands.

The reddit message board “BuyItForLife” receives 1.7M weekly visitors. There the focus seems to be on brands that, as the title suggests, last. Some items are expensive status symbols like Rolex watches and Birkin bags, but others are more practical items like eiderdown bedding, Montblanc fountain pens, Le Creuset cookware, knives with a lifetime of sharpening, Canada Goose coats that can be passed on as a family heirloom, microwaves that don’t break within a year or two, Zojirushi rice cookers, Dyson vacuums, Viberg boots, Barbour’s waxed jacket, Herman Miller office chairs, and on the more affordable side—Stanley water bottles. And yes, my coveted Mason Pearson brush is also a common recommendation. But most surprisingly, there’s even a laptop that users believe can last a lifetime. The purpose—at whichever price point—is the pursuit of quality and longevity.

According to Popovich, going with a long-standing brand helps consumers reduce the cognitive effort involved in making a choice. “Shoppers don’t have to work hard to evaluate it; the feeling of familiarity makes it seem like an obvious decision,” she says, adding, “This is due to cognitive fluency, which is the feeling of ease we get when our brain can process information quickly and without effort. This feeling influences our judgments, making us more likely to perceive information as truthful and likable, simply because it’s familiar.”

I’ll keep that in mind as I inch toward buying that expensive hairbrush that somehow keeps feeling more and more like the “obvious” choice.