Woo Woo Returns: 60 Minutes and the Revival of Television Gullibility

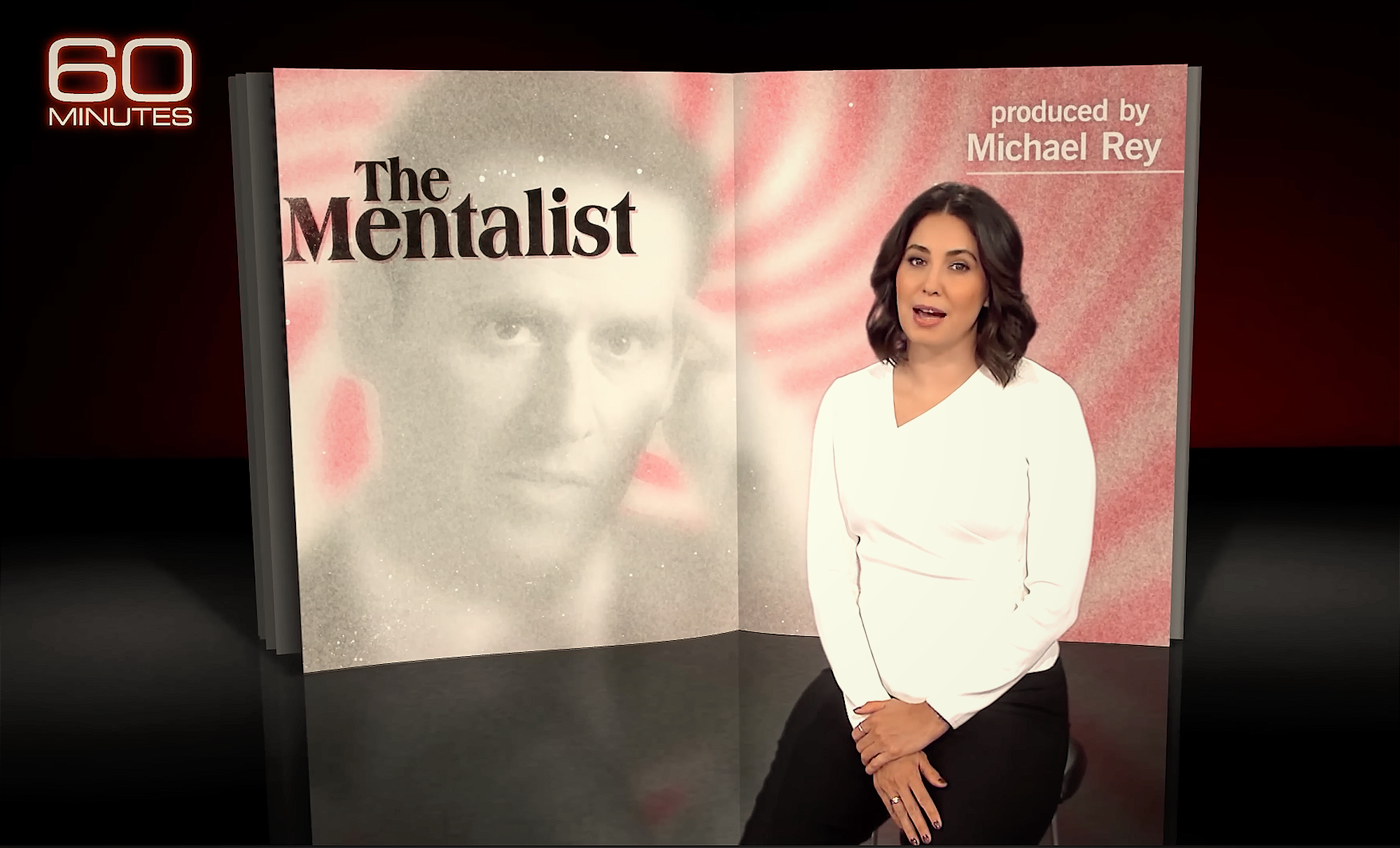

“There’s no way,” gasped NFL star Russell Wilson as mentalist Oz Pearlman seemingly plucked an ATM pin code from his mind on 60 Minutes. The venerable news program, known for hard-hitting journalism, looked more like awestruck children at a magic show as Pearlman dazzled correspondent Cecilia Vega with his “psychic” feats. During the segment, Pearlman correctly divined Vega’s childhood bedroom poster and even her dream vacation destination, prompting 60 Minutes to bill him as a master at making people think he can read minds.

It was an impressive performance—but if the late skeptic and magician James Randi taught us anything from his battles with spoon-bender Uri Geller, it’s that such “mind reading” is nothing more than very good parlor tricks in new packaging. Indeed, not once did Pearlman admit that he was using well-honed magic tricks to fool his credulous audience, instead choosing to blur the lines by attributing his work to an extensive study of psychology and body language. Pearlman did, however, admit his act “is based on a big lie—that I can read minds,” a confession that should give pause to any too-eager believer.

From Uri Geller to Oz Pearlman: Old Wine in New Bottles

The astonishment on 60 Minutes carries an eerie echo of the 1970s, when self-proclaimed psychic Uri Geller convinced a great many people that he could bend spoons and read thoughts by paranormal means. Back then, even respected TV host Barbara Walters was initially taken in—until James Randi stepped up to expose the ruse. The key difference, of course, was that Randi never pretended to be supernatural like Geller. He admitted he was deceiving her. His craft was artifice, not alchemy. On Barbara Walters’ Not for Women Only, the ever-composed Walters was nearly giddy as she displayed a key Uri Geller had bent “with his mind.” Without missing a beat, Randi took another of her keys and bent it right in her own hands. When he told her it was merely “woo woo”—his wry term for a magician’s trick—the triumphant smile drained from Walters’ face, replaced by an embarrassed grin that seemed to say, “I can’t believe I fell for that.”

He dazzles the public and media with abilities that look like real mind magic, while keeping the methods hidden.

Randi famously assisted Tonight Show host Johnny Carson (a former amateur magician) in orchestrating Geller’s on-air flop (by preventing any trick props). Randi and other skeptics went on to document how Geller’s feats were done by ordinary means; for example, in Skeptic magazine Randi detailed Geller’s “moving compass” stunt as nothing more than a conjurer’s trick. Fast forward to today: Oz Pearlman may not claim supernatural powers (he pointedly told 60 Minutes, “I’m not a psychic, I just read people”), but in practice he follows the Geller playbook—dazzling the public and media with abilities that look like real mind magic, while keeping the methods hidden. And judging by 60 Minutes’ wide-eyed reaction, the media has learned little since the Geller era about not buying into the illusion hook, line, and sinker.

Inside the Mentalist’s Bag of Tricks

How exactly does Pearlman pull off what looks like telepathy or precognition? He offers a benign explanation: keen observation, psychology, and influence. That is, by observing subtle cues in body language, eye movement, and speech, he constructs a psychological profile of his subject—then subtly steers them toward choices that appear spontaneous but are anything but. In other words, Pearlman frames his talent as an acute ability to read and manipulate human behavior, no paranormal powers needed.

But veteran magicians and skeptics insist there’s a lot more trickery behind the scenes than Pearlman lets on. In the world of mentalism—the art of creating the illusion of mind-reading—performers rely on a mix of old-school magic techniques and modern-day cunning. Some likely ingredients in Pearlman’s repertoire include:

- Information Gathering: Many “miraculous” mind-reading feats developed by stage magicians are achieved by researching the subject ahead of time. Personal data from public sources (social media, interviews, even friends and family) can provide the answers to questions he later asks as if divining them. When mentalists guess somebody’s favorite ice cream or first love, it’s often because they already found it out beforehand.

- Forces and Pre-Show Setups: Mentalists often force a choice or outcome. In many routines, the participant’s “free choice” is an illusion—the mentalist has designed the trick so that picking a particular name, number, or item is the only possible outcome. Pearlman hinted at this when he revealed “there are certain moments where you’re about to change your mind, and I move you in another direction… your mind works in a predictable way.” By using cleverly crafted props or a misleading sequence of events, he ensures the big reveal was inevitable all along. (When a stunned person says, “How could you know I’d pick that?,” the answer is often “Because you really had no choice.”)

- Sleight of Hand and Gadgets: Classic magic methods play a outsized role in mentalism. For instance, when Pearlman dramatically opens a prediction from a sealed envelope, skeptics suspect he often writes the “prediction” in the moment using hidden aides (like a thumb-tip writer, hidden mirror, or secret compartment) after he already knows the answer. In the much-hyped case of Pearlman guessing Joe Rogan’s ATM pin code, it’s far more likely he obtained the pin through sneaky means than by mind-reading. Pearlman may have rigged a real ATM keypad with a hidden overlay (a practice all too common amongst real-world scammers) or a tiny camera to record every button Rogan pressed, essentially a magic trick crossed with a hacker’s touch. Sure enough, Pearlman guided Rogan to think of his ATM number (after dismissing a truly “random” number guess) and then declined to repeat the feat with a different pin, suggesting he stuck to the one piece of information he knew ahead of time. This is classic misdirection: make the audience believe you’re pulling thoughts from their head, while the real solution is a prepared prop or pre-gathered data.

- Showmanship and Psychology: To his credit, Pearlman is a master showman. He peppered his 60 Minutes appearance with dramatic pauses, intense stares, and rapid-fire patter about intuition. This theatrical flair primes people to believe he’s employing some exotic technique like “reading micro-expressions” or using hypnosis. However, professionals note that much of this is smoke and mirrors. He looks closely at faces, etc., to appear like he's doing more than he is while he seizes on any facial twitch to ascribe meaning to it as if it were significant. By invoking these psychology concepts, Pearlman adds a scientific mystique to his act. It’s all part of the illusion: modern audiences know about body-language reading and want to believe he’s using a Jedi-like skill, so Pearlman skillfully encourages that belief, all while relying on much more mundane trickery in the background. And he doesn’t really hide that fact: “I’m not gonna tell you [the exact techniques]. That doesn’t do well for my job security,” Pearlman laughed when pressed on his methods.

In short, Oz Pearlman’s mind-boggling routines are built on deception: a mix of savvy preparation and age-old magic tricks dressed up as psychological prowess for the 21st century audience.

Why Do Smart People Fall for It?

It’s tempting to assume that only the naïve or uneducated would be taken in by acts like Pearlman’s. Yet the irony, as Pearlman himself gleefully points out, is that “people who are very intelligent are much easier [to fool] because their mind is regimented in a certain way.” Highly educated folks, from tech CEOs to seasoned journalists, often have confidence in their reasoning—which can make them over-confident that they “can’t be tricked,” leaving them blind to the deception. In the 60 Minutes piece, Cecilia Vega is no doubt a sharp reporter, but her focus on experiencing the “wow” factor firsthand may have overshadowed a healthy skepticism. After all, when you’re busy reacting to a mind-blowing personal revelation on camera, it’s hard to step back and ask, “Hey, could he have found that out on Google?”

Highly educated folks, from tech CEOs to seasoned journalists, often have confidence in their reasoning.

Skeptics argue that media outlets often invite being fooled by approaching performers like Pearlman as if they truly might have special powers. Mentalist and skeptic Mark Edward notes that many journalists don’t do their homework on these acts. “News people seldom care or have time to research past their own noses,” he laments, describing how an Inside Edition reporter fell “hook, line, and sinker” for Pearlman’s routine and earnestly asked, “You mean he really isn’t reading minds?” In the rush to tell a sensational story, basic fact-checking, like consulting a magician or skeptic, falls by the wayside. As a result, TV segments gravitate to entertainment over explanation. The performer gets to preserve the mystique, the audience at home is enthralled, and the tough questions never get fully addressed on-air.

No one, including all the famous mentalists and psychics, ever passed the controlled tests.

The pattern is nothing new. Decades ago, 60 Minutes aired credulous segments on supposed faith-healers and psychics, only to face embarrassment when skeptics debunked those claims later. James Randi famously offered a $1 million prize to anyone who could demonstrate genuine paranormal abilities under scientific conditions. That money was never claimed. No one, including all the famous mentalists and psychics, ever passed the controlled tests. That sobering fact tends not to make it into the primetime puff pieces, but it remains a giant red flag waving above all these astonishing acts.

Toward a More Skeptical Spotlight

None of this is to say that Oz Pearlman isn’t a gifted performer. He certainly is, and by all accounts he leaves his audiences delighted and mystified. The issue, rather, is how his feats are framed by the media. When a program as influential as 60 Minutes presents a mentalist’s act with wide-eyed wonder but little critical scrutiny, it edges toward promoting pseudoscience (even if unintentionally). It’s the job of skeptics and science communicators to provide the missing context: reminding the public that what looks like mind-reading is, in reality, a well-choreographed con performed using the same methods deployed by stage acts in Las Vegas. Extraordinary claims (like psychic powers or flawless intuition) require extraordinary evidence, and a TV stunt, however entertaining, is not evidence of anything except a talented illusionist at work.

Perhaps the next time a celebrity “mind reader” is booked for an interview, the producers could also invite a skeptic or magician to weigh in. Imagine a follow-up segment where 60 Minutes deconstructs Pearlman’s miracles with the help of an expert. Now, that would be real investigative journalism! Until then, we skeptics will keep pointing out that the emperor of “mind magic” has no paranormal clothes. Oz Pearlman’s act isn’t a window into the supernatural, or into some superhuman power of reading body language; it’s a mirror reflecting our own willingness to be fooled, and a reminder that a critical eye is the best defense against even the most charming con.

67 percent of Americans believe they’ve had at least one paranormal experience.

The lack of media scrutiny also explains why so many people believe in the paranormal and supernatural. A 2022 poll by YouGov found that 67 percent of Americans believe they’ve had at least one paranormal experience (e.g., unexplained presence, hearing voices, seeing a ghost or UFO, etc.). Magician and skeptic Jamy Ian Swiss says that skeptics “especially go after these claims that are against the laws of physics…We're advocating for using science as a way to view the world and solve the problems of the world.” But it is an uphill battle because woo woo is big business. Take, for example, homeopathy, the idea that a substance causing the symptoms of an illness becomes an effective treatment when diluted beyond detection. One recent estimate puts the U.S. homeopathy market at $2.7 billion in 2024, projected to reach $6.8 billion by 2035.

Homeopathy “potentization” purports to increase the perceived potency of a substance through a series of serial dilutions and vigorous shaking. In practice, homeopathic remedies are often diluted to the point that not a single molecule of the original ingredient remains. What’s left is pure water (or sugar pills). The claim that water retains a “memory” of substances it once contacted has never been demonstrated under controlled conditions and directly contradicts molecular physics, chemistry, and thermodynamics. Every rigorous clinical trial and meta-analysis to date, whether from The Lancet, Cochrane Reviews, or the UK’s House of Commons Science and Technology Committee, has found homeopathy performs no better than a placebo.

Related to homeopathy is holistic medicine, which presents itself as a kinder, more humane alternative to the cold precision of modern biomedicine. It promises to treat “the whole person”—the mind, body, and spirit—an appealing notion to anyone who feels unseen by a healthcare system that too often reduces patients to charts and lab values. In principle, such a patient-centered philosophy is laudable. But in practice, “holistic” medicine has become a marketing umbrella under which evidence-based lifestyle advice (nutrition, exercise, stress reduction) mingles freely with therapies that defy science altogether (e.g., energy healing, reiki, and detox regimens). The rhetoric of balance and “natural healing” creates an aura of legitimacy while quietly dispensing with the need for proof. As one critic put it, holistic medicine often sells empathy in place of efficacy.

The danger lies not in caring about the whole person but in abandoning what allows medicine to work. Holistic practitioners frequently justify their claims with anecdotes, intuition, or appeals to “ancient wisdom,” yet when tested under controlled conditions, their results dissolve to the level of placebo. Worse, patients persuaded by the promise of “natural” cures may delay or reject proven treatments, mistaking philosophy for therapy. The irony is that genuine medicine has become more holistic over time, incorporating nutrition, psychology, and preventive care, but it does so anchored in evidence. When “holism” becomes an excuse for pseudoscience, it ceases to heal and begins to harm, replacing reasoned care with comforting illusion.

The harm isn’t just theoretical.

The harm isn’t just theoretical. While homeopathy and holistic medicine may be chemically inert, their cultural influence is not. Dressing superstition in the language of medicine encourages the public to distrust evidence-based science and substitute pseudoscience for genuine treatment. This can delay proper diagnosis or lead patients to forgo effective therapies altogether.

60 Minutes’ glowing report on Oz Pearlman demonstrates how powerful belief, when reinforced by anecdote, marketing, and wishful thinking, can transform mundane parlor tricks into news-worthy mastery of “human psychology” and “body language.” In that way it is no different than homeopathy, along with other nonsense fields like astrology, energy healing, detox cleanses, and psychic readings, to name just a few. CBS should know better.