Boredom

“All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.”—BLAISE PASCAL

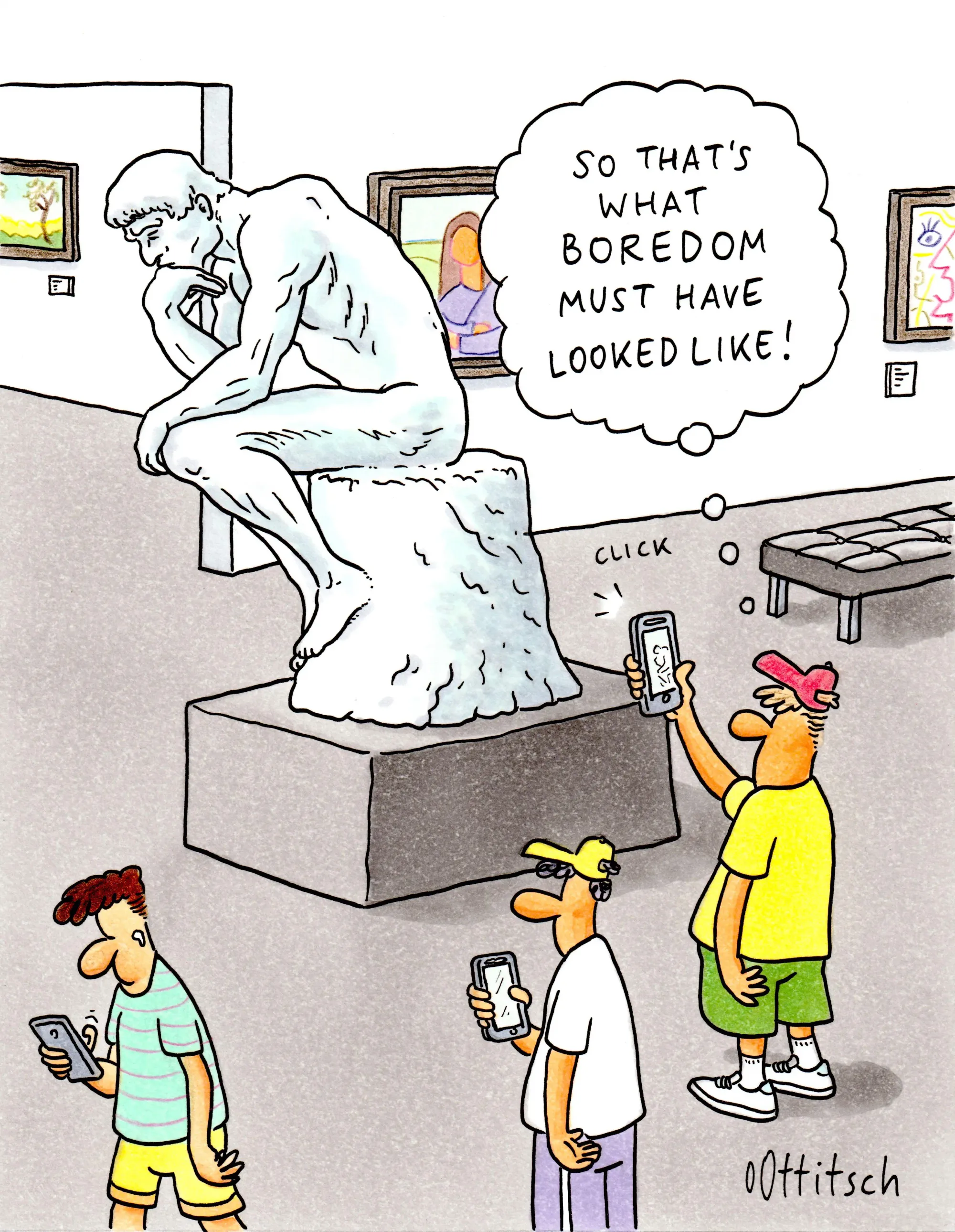

According to the American Time Use Survey,1 conducted by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Americans currently enjoy more leisure time2 than at any point in history; yet 83 percent of us report spending none of this time whatsoever “relaxing or thinking.” Instead, we are trapped in a casino of likes, retweets, and dopamine-soaked drudgery—consuming content so hyperstimulating that relaxing is impossible and thinking is unnecessary. The average American, today, spends six hours3 awake “consuming content,” checks their phone 205 times a day4 (once every five minutes) and lives in a house with 17 Internet-connected screens.5 More of us have a Facebook account6 than a primary physician;7 more have easier access to Wi-Fi8 than clean air;9 and more have the ability to order UberEats10 than to microwave a meal.11

The rhythm of American life has become twitchy, impulsive, allergic to lag—demanding one-click purchases, same-day shipping, and fast-lane checkouts. Our decisions are made mid-scroll, our interactions unfold in push notifications, and our enterprise—well, one ad campaign12 said it best: “Instant gratification just got faster. Shop Vogue-dot-com.”

We’ve grown so intolerant of delay that we can’t sit through a full microwave countdown before intervening—preferring to eat it lukewarm than wait for zero. We don’t read, we skim. We don’t date, we match. According to data from Spotify,13 listeners skip 24 percent of songs within the first five seconds and 49 percent of songs before they end. On TikTok, meanwhile, users decide if the video is worth their time within three seconds of viewing;14 and if it doesn’t load within two15—on to the next. Following suit, Hollywood writing rooms have been instructed to keep all scenes under five pages (i.e., five minutes) and to never let a character speak more than five lines uninterrupted. And still, 94 percent16 of us make sure to keep our smartphones on hand just in case the next scene can’t hold off the itch to scroll.

We are numbed-out, overstimulated into indifference, and underwhelmed by everything.

Silicon Valley has unleashed a line of products (such as the iPhone, social media, and streaming platforms) so efficient at delivering pleasure that all else feels gray, drab, and not worth it. The baseline of stimulation has been raised so high that anhedonia,17 a psychological condition best defined as chronic joylessness or an inability to experience the beauty of ordinary life, is increasingly being diagnosed in those of us who are most immersed in these god-like technologies.

The New York Times columnist David Brooks calls it “The Junkification of American Life”18—a diet full of flavor and void of nutrients. A culture that feels like it’s limping forward; “stale,” “stuck,” and “unmotivated”—Google search terms that have all increased by at least 200 percent in the last two decades. We are numbed-out, overstimulated into indifference, and underwhelmed by everything.

Some have labeled it more simply—a crisis of boredom. A nation where half the workforce says they are bored19 with their jobs20 (69 percent if measured by “feeling engaged”21), close to 40 percent22of all of us claim to be bored with our social lives, and two thirds23 of millennials report being plainly “bored with life.” According to research, young Americans today are more “boredom-prone”24 than at any time in history—so much so that Gen Z has been crowned the “the bored generation.”25 And for many, the feeling is a strange kind of exhaustion where more than half our day is spent sitting,26and yet we feel tired—tired of work, tired of leisure, tired of a culture so fried with cynicism and unseriousness and pointlessness.

But the crisis is misdiagnosed. The opinion that “work sucks” or that there’s “nothing good on Netflix” is not boredom. It is frustration, it is aggravation, it is restless dissatisfaction, it is the aching weight of unmet expectation. It is all of these things and more—but above all, it is the mistake of defining boredom by how it makes us feel, rather than by what it truly is: confusing the symptoms with the illness, like mistaking a fever for the infection itself.

Americans today feel more anxious, more adrift, and more unhappy. We are also—never bored.

Definitions of Boredom

In 1933, the novelist James Norman Hall wrote a letter to the Concise Oxford English Dictionary.27Defining boredom as “being bored; ennui,” Hall explained that, “To define [boredom] merely as “being bored,” appallingly true though this may be, is only to aggravate the misery of the sufferer who, as a last desperate resource, has gone to the dictionary for enlightenment as to the nature of his complaint.”

Being bored is not just a pause in the dopamine drip, but the void into which thought, desire, and distraction rush to take shape.

Boredom, throughout history, has stubbornly resisted a precise definition, evading philosophers, scientists, and linguists alike. It is a word that means both too much and too little—the kind of concept that everyone assumes they understand until it comes time to explain it. Some have defined it as a lack of external stimulation,28 others as a kind of emotional recession,29 and still others as the leaden stupor30 of a mind unable to decide what it wants. It has been called a symptom of modernity,31 a biological alarm system,32 a spiritual sickness,33 a privilege, and a curse. It drifts between the trivial and the profound; the universal and the personal; as likely to strike in a fluorescent-lit waiting room as in a velvet-roped champagne room. As the psychologist Adam Phillips put it:

[W]e should speak not of boredom, but of the boredoms, because the notion itself includes a multiplicity of moods and feelings that resist analysis; and this, we can say, is integral to the function of boredom as a kind of blank condensation of psychic life.34

Broadly speaking, however, boredom is usually thought of in one of two ways. The first is as a deficit of meaning35—a sense of purposelessness and existential disinterest. The second is as a deficit of attention36—a state where the mind is unoccupied and without focus. The first, what may be called cultural boredom, is abstract, less urgent, and entirely man-made—an unintended byproduct of natural selection’s misalignment with modern life. The second, what may be called biological boredom, is much older and more primal—an evolutionary function woven into the logic of selection and shared across species. In short, there is boredom as defined by nature, and boredom as defined by humans.

But perhaps the more useful distinction is between feeling bored and being bored. Like the difference between feeling alone and being alone; one is a psychological state and the other is a material circumstance. One a measure of subjective experience, the other a measure of objective conditions. What this means is that feeling bored is self-reported—you can only know if someone feels bored by asking them. But to know if they are bored, you don’t need words—you need observation: brain scans, environmental situations, introspective awareness, and so on.

Of all the available measures, arguably the most comprehensive marker of being bored is the activation of what neuroscientists call the brain’s default mode network. The default mode network37 describes a network of brain regions that are more active when an individual is not focused on the outside world and is instead engaged in internal thoughts, daydreaming, self-reflection, or other forms of “mind-wandering.” Put simply, it is the brain alone with nothing but its own thoughts.

In the most absolute terms, being bored is the condition of nothingness.38 It is not something felt but something endured; not a disturbance, but an absence. It is the blank space behind every human experience; the raw foundation of existence before feeling or meaning is imposed. Being bored is not just a pause in the dopamine drip, but the void into which thought, desire, and distraction rush to take shape. It is not merely the opposite of stimulation—it is the state from which all stimulation is an escape. There is boredom, and from it, everything else grows.

Being bored is the ground floor—the bare, stimulus-poor reality before the mind knows what to do with itself. Biological boredom, then, is conscious experience’s most primitive reflex in response to this nothingness.

Biological vs. Cultural Boredom

It is perhaps evolution’s strongest and most universal selection pressure39—what the Buddhists call “dukkha”—and what in the West best translates as “unsatisfactoriness.” In their book, Out of My Skull: The Psychology of Boredom,40 neuroscientist James Danckert and psychologist John Eastwood describe it as a feeling similar to tip-of-the-tongue syndrome—a sensation that something is missing, though we can’t quite say what. It is living with the frustration that what is is never as good as what could be. Because to be rewarded for wanting more41—more stuff, more status, more sex—instead of for having enough, describes life’s most fundamental adaptive strategy. Across species, individuals who are happy with less than the greediest amongst us are outcompeted, outreproduced, and ultimately erased from the gene pool. Enough is never enough—because too many successful copies is an impossible error.

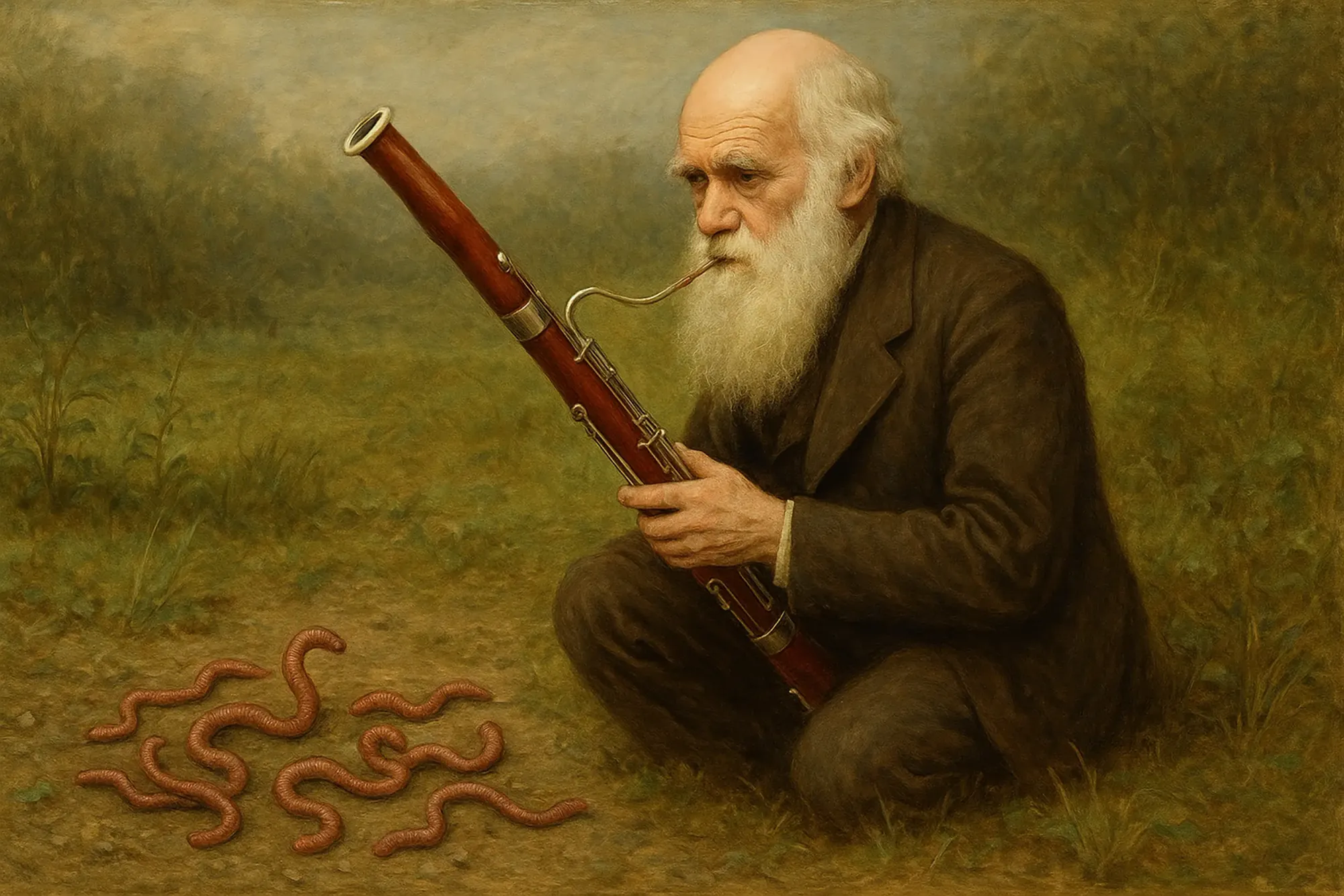

But wanting more is only half the equation. Our thirst isn’t just for accumulation, but for variety. The same old thing, no matter how pleasurable, is rarely as tempting as a new thing. It is what biologists call novelty-seeking behavior: the tendency to explore and engage with new stimuli in the environment.42 As Darwin put it in 1859: “It is in human nature to value any novelty, however slight.”

Chasing newness leads organisms to discover greater sources of food, water, and other vital resources.43 And in a world of shifting climates, changing ecologies, and constant competition, those willing to try new behaviors or adapt to new habitats often have the advantage.44 Attunement to the unfamiliar also sharpens an organism’s ability to detect threats45 early, increasing the odds of escape before it’s too late. It is a behavior that keeps creatures scanning,46 searching, and restless in their pursuit of the next new thing. And when the behavior stalls, when we stop experiencing novelty, boredom rushes in as a biological fail-safe against stagnation. As Danckert et al. put it:

Our survival would be short-lived if we were unable to engage our cognitive abilities in the service of achieving our goals or responding adroitly to environmental demands. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that we have been shaped by evolutionary forces to experience the aversive state of boredom when our cognitive resources are not being optimally utilized.47

For billions of years, operating in high-stakes environments where life-sustaining resources were few and far between, natural selection has been relentlessly designing a system where psychological stress48 is only ever relieved by hard-earned bursts of feel-good endorphins like dopamine or serotonin. In short, our brains were wired to over-worry and under-enjoy;49 because seeing a stick and thinking it’s a snake is less costly than seeing a snake and thinking it’s a stick.

The root of today’s suffering is that we are operating on an inherited psychological system where the most stable evolutionary strategy is a life filled with stress and anxiety.

Animal studies have found that, for most, over 70 percent of waking life is spent being afraid, stressed, or anxious. And in primates, where social conflict is a bigger part of the equation, this number rises to 85 percent. Research also suggests that negative feelings are felt twice as strongly as positive ones and that cortisol—the primary stress hormone—delivers effects that last thirty to sixty times longer than dopamine or serotonin, further exacerbating this hellish existence.

The root of today’s suffering is that we are operating on an inherited psychological system where the most stable evolutionary strategy is a life filled with stress and anxiety, and so no matter what the outside conditions (i.e., full belly, empty belly, rich, poor, etc.), the inside machinery will always adjust the experience meter back toward unbearable static. It is the reason why zoo animals, spared from hunger and fear, pace endlessly, gnaw at their own limbs, or pluck themselves bald in fits of unseen agony.50 It is their brains demanding a stress that no longer exists.

Americans today live a more cushioned existence than any population—human or otherwise—in history. Parents no longer watch half their children die before the age of five.51 Smoke-suffocating factories no longer employ eight year olds52 until they run out of fingers to lose. Our laws no longer punish people for baking bad bread by boiling them alive.53 The flu no longer sweeps through towns like a biblical reckoning. Cognitively impaired 13-year-olds54 no longer inherit absolute power;55 and we no longer expect to drop dead56 before the age of 30.57

The average American lives in a home with climate control, clean water, and a refrigerator stocked with more food, flavor, and convenience than kings of old.58 Thomas Jefferson, one of the richest Americans of his time, never went a winter where he wasn’t cold in his own home, complaining that his pens would freeze, and spending every morning chiseling the ice off his writing desk.59 Even the poorest among us have access to medical care, public education, and safety nets that would have been unthinkable in previous centuries. The daily struggles60 that once consumed our ancestors—finding food, surviving disease, avoiding violence—are no longer the defining features of life. As the comedian Louis C.K. put it:

New York to California in six hours. That used to take 30 years, to do that; and a bunch of you would die on the way there. You’d get shot in the neck with an arrow and you’d go—“euughhh”—and fall down. And the [others] would just bury you and put a stick there with your hat on it and keep walking. And one of ’em would fuck your wife and have three babies. And all the old people would die. You’d be a whole different group of people by the time you got to California.

And yet, we are not any happier. If anything, we seem to suffer more in new and increasingly abstract ways—drowning in antidepressants, therapy bills, and vague complaints about “burnout.” Over just the last decade, depression rates have more than tripled,61 anxiety in young people has increased by nearly 150 percent62 and deaths of despair—a term coined by the economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton to describe deaths from alcohol, drugs, and suicide—have surged to unprecedented levels. We are more unhappy today than at any time since Gallup started asking the question in 1948, and according to one study, more anxious today than even during the Great Depression.63 In an age where Americans spend more money on entertainment than fresh produce,64 mental health, as described by the U.S. Surgeon General, has become “the crisis of our times.”65

In a society where we have no thing (no predators, no famine, no war) to torment us, nothing itself becomes the torment. In other words, leisure curdles into boredom—a hell so unbearable that international law recognizes it as a torture device (i.e., solitary confinement) and NASA assigns its astronauts busywork to safeguard against it.66 Studies have found we’d rather blast our ears with the sound of a screaming pig67 than listen to nothing or engage in dangerous behaviors such as drug use, erratic driving,68 or high-risk financial speculation in order to avoid boredom. A series of studies, published in Science,69 found that two thirds of participants would rather self-administer electric shocks than endure just 15 minutes devoid of external distraction; with a similar majority saying they’d pay money to never experience such boredom again.

Important to note is that all the aforementioned examples of boredom involve individuals unable to sit alone with their thoughts; trapped in the claustrophobia of sensory-deprived consciousness. This is, of course, not the kind of boredom most Americans today are experiencing—opening apps, closing apps, reopening the same apps. The kind where, instead of being unable to sit with it for 15 minutes, we are unable to sit without it for more than 15 minutes. The kind that feels like boredom, looks like boredom, but, in being, is not boredom. It is cultural boredom.

If biological boredom is a negative feeling triggered by the absence of stimulation, cultural boredom is the feeling of boredom untethered from that absence—an emotional layer we’ve learned to apply even when nothing is missing. In other words, biological boredom is a response to being bored; cultural boredom is the invention of boredom as a feeling in itself—freestanding, self-replicating, and often entirely disconnected from a stimulus gap.

The Invention of Boredom

In 1872, Charles Darwin published The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, a book that sought to explain emotions as a product of natural selection. He catalogued the tics and tremors of anger, the widened eyes of surprise, the drooped mouth of sadness. He sketched out fear, joy, and disgust—each encoded in the brute, observable mechanics of the body and universal enough to echo across species. What Darwin did not catalog—as an emotion, a behavior, or even a mode of suffering—is boredom. In fact, the word is not found once in the entire book.

But this omission was not an oversight. It was merely a reflection of the times. Indeed, while it was possible in the English language to be “a bore”70 in the 18th century, it was not until the mid-19th century that the noun was used to describe a subjective feeling; made popular by Charles Dickens in his 1852 novel Bleak House, where he used the expression “bored to death” six times. Before this, languages lacked a direct equivalent for the modern sense of boredom, suggesting that the experience, or at least its recognition as a distinct emotional state, was not prevalent. As Patricia Meyer Spacks put it in her book, Boredom: The Literary History of a State of Mind:

Boredom was in the eighteenth century a new concept, if not necessarily a new event. The emergence of a new concept marks a significant cultural happening because it allows articulation of fresh ways to understand the world.

It’s not that boredom didn’t exist before modernity—it’s that it wasn’t conceptualized. Evolution shaped our brains to avoid stagnation, but it didn’t give us a word for it. Earlier societies had the same biological restlessness, but they interpreted it through different lenses—as laziness, as luxury, as opportunity.

In ancient Egypt,71 idleness was not a feeling but a failure; a lapse in duty, a mark of social uselessness. Homer’s epics, too, interpreted inactivity not as boredom, but as part of the hero’s journey; for example describing the malaise Odysseus felt72 in exile as nostos—a sort of homesickness and noble suffering tied to love and destiny. Even Aristotle, who gave leisure its own category73—scholé—saw it not as a void to be filled, but as the highest form of human activity; a space allowing contemplation and virtue.

It was not until Seneca, writing in the first century CE, that something like cultural boredom began to take its modern shape. In his Moral Letters,74 he describes a condition of inner agitation—taedium vitae,75 the weariness of life—as arising not from hardship, but from the sterile repetition of unworthy days. “How long shall the same things be?” he asks. “Surely I shall yawn, I shall sleep, I shall eat, I shall be thirsty, I shall be cold and hot.” Still, it would be wrong to read this as Seneca feeling bored. Because, for him, taedium vitae wasn’t a psychological problem—it was a philosophical one. His diagnosis wasn’t understimulation, it was misuse of time; not a deficit of dopamine, but a crisis of character; not complaint, but criticism.

By the fourth century, the feeling had mutated again—this time into a theological problem. In the solitude of early Christian monastic life, restlessness became a matter of the soul, and boredom, not yet as we know it, was repackaged as acedia.76 One of the “eight evil thoughts” identified by the early monks—precursors to the Seven Deadly Sins—it was considered more dangerous to spiritual life than lust or pride. Acedia combined weariness, melancholy, restlessness, and despair. As described by the “desert father” Evagrius Ponticus in 395 CE:

The demon of acedia—also called the ‘noonday demon’—is the most oppressive of all the demons. He attacks the monk about the fourth hour (10 a.m.) and besieges his soul until the eighth hour (2 p.m.). It makes the sun seem to slow, or stop, and the day appear fifty hours long … (it) instills in him a dislike for the place and for his state of life itself.77

But acedia, though more of a free-range malaise, was still tethered to circumstance—to solitude, sameness, and the struggle for divine purpose. It wasn’t yet the free-floating, ambient dissatisfaction of modern life; where boredom just is. Acedia wasn’t a mood; it was a visitation—an affliction that arrived in a specific place, at a specific hour, demanding defense by prayer, ritual, and will.

It wasn’t until the Enlightenment that cultural boredom, as we know it, was fully realized. No longer a spiritual affliction or a philosophical agitation, it began to appear as a secular feeling—one that drifted loose from cause and context; a fog that needed no trigger. But even then, it was not a democratized experience. Among the aristocracy and intellectual elite, this new feeling became a sign of refinement78—proof that one’s material needs were so thoroughly met that only dissatisfaction remained. To be bored was to be above it all: too educated to be easily amused, too cultured to be entertained by work, too important to care. In salons and diaries, writers complained of boredom79 the way others might complain of melancholy—a side effect of privilege, indulgent and vaguely pleasurable. Boredom in this era was not merely tolerated but stylized—an attitude both fashionable and self-congratulatory. As the philosopher Søren Kierkegaard, part of this new ennui class, observed in 1843:

Those who bore others are the plebians, the mass, the endless train of humanity in general. Those who bore themselves are the elect, the nobility.80

If nature designed boredom to push us into action, the Enlightenment gave us the capacity—and the luxury—to sit with it. To not just be under-engaged; but to be aware in the way of expectation—alert to the absence of something better and agitated by its failure to appear.*

But even after receiving a dictionary definition in the late 19th century, the concept of boredom was still not quite as we know it. In Freud’s early case histories, patients complained of ennui, neurasthenia, melancholia, a vague sense of internal collapse,81 but they were never bored—they were ill. In fact, the word boredom barely appears in Freud’s published corpus. The world would have to wait another two generations for the feeling to be downgraded from neurosis to lifestyle; and another generation, even after that, for scientists to reach consensus on boredom as a distinct emotion. Studies82 in the 1940s, for example, treated it more as a productivity issue83 than a psychological one, often linking it to factory conditions and attention spans.

It wasn’t until the rise of consumer society84 that boredom mutated into a crisis of entertainment; when television, radio, advertising all promised to make boredom obsolete. But in doing so, they redefined it—as something solved by consumption, content, convenience. And by the 1960s, boredom had gone from assembly-line hazard to middle-class epidemic, with Reader’s Digest,85 in 1976, making it official: “Boredom has become the disease of our time.”

In order to endure boredom, one must have a purpose—but in order to discover that purpose, one must first endure boredom.

The history of boredom is—like much else—in a larger sense the history of our interpretive frameworks. As the philosopher Alan Watts put it:

This whole [world] has its history in ways of thinking—in the images, models, myths, and language systems which we have used for thousands of years to make sense of the world. These have had an effect on our perceptions which seems to be strictly hypnotic.

We are aware, not of the world but as the world. Things are, as Shakespeare put it so long ago, neither good nor bad. It is our thinking that makes them so. And so for the Romans, being bored was leisure’s reward—something to be mastered; for the early-age Christians, it was moral weakness—something to be resisted; for the enlightenment aristocrats, it was an air of distinction—something to be paraded; and for us, we’re like Homer—slumped in comfort, feeling antsy, agitated, and unsatisfied in a hyper-entertainment culture where “I’m bored” has become a verbal reflex and catch-all for most any feeling of discomfort. As the French poet Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly put it:“Oh! Ennui! Ennui! What an answer to everything.”86

Biological boredom—in the modern century—has been buried beneath an avalanche of clicking, scrolling, and streaming so total and crushing that we are only left with cultural boredom—no longer the costume of aristocratic refinement, but the price of compulsory participation. We are not bored by choice—we are, today, a slave to cultural boredom.

Innovation and Boredom

“[A] generation that cannot endure boredom will be a generation of little men, of men unduly divorced from the slow process of nature, of men in whom every vital impulse slowly withers as though they were cut flowers in a vase.”—BERTRAND RUSSELL

They stood for hours, day after day, cycling through the same motion: dropping paper, picking it back up, dropping it, picking it up.87 In the fall of 1901, already two years into their experiments, the Wright brothers were not yet pioneers of flight—they were two men (in their early 30s); watching the same piece of paper fall the same way, again and again and again, for months. The work was not thrilling. It was silent, grueling, and bureaucratically exact. Entire seasons at Kitty Hawk were spent just sitting—Orville counting seconds, Wilbur watching gulls. As one observer recounted:

[W]e couldn’t help thinking they were just a pair of poor nuts. We’d watch them from the windows of our station. They’d stand on the beach for hours at a time just looking at the gulls flying, soaring, dipping.88

Over years, they calibrated rudders by tenths of a degree, took wind readings, and filled notebooks with data that, to the outside observer, seemed tediously unvarying. Weeks and months of nothing—no insight, no change, no end—just failure. They weren’t scientists. They weren’t engineers. They did the work. That was all. And slowly, eventually—it was boredom that taught them what lift was; boredom that refined itself into the equations of flight. The breakthrough wasn’t sudden; it was sedimentary—layered atop countless afternoons of tedium, repetition, and quiet attention. For Orville and Wilbur Wright, boredom wasn’t a side effect—it was the method.

Five generations later, young Americans seem increasingly incapable of doing what they did. A recent study published in Nature found that, across all fields, “papers and patents are increasingly less likely to break with the past in ways that push science and technology in new directions.”89 Another study found that the number of “important events in the history of science and technology”90 has plummeted by over 50 percent in the most recent generation (i.e., millennials). A trend that is reflected in the average age of Nobel Prize winners who, across virtually every field—from physics to literature—keep getting older,91 and who’s quality of discovery, as rated by scientists, keeps getting worse.92

The rhythm of American life has become twitchy, impulsive, allergic to lag—demanding one-click purchases, same-day shipping, and fast-lane checkouts.

The Wright brothers achieved flight in 1903, crash landing a one-man aircraft less than 800 feet from the launch site. Half a century later, commercial planes were making the trip from New York to LA nonstop in less than six hours. Now it is a full century later—and it still takes about six hours. The economist Tyler Cowen has termed it “The Great Stagnation;” from a century where we split the atom, put a man on the moon, electrified cities and invented the Internet to today—a century that, so far, has produced 18 iOS updates and flatter television screens.

Some argue this stall is inevitable93—that the 20th century harvested the obvious advances, solving all the simple problems and leaving a thicket of harder, slower puzzles. That’s part of it, sure—but art and entrepreneurship have no natural ceiling. And yet, these too are in freefall. Americans are, today, by most measures, increasingly uncreative and less able to build businesses. Scores on the Torrance test—creativity’s most reliable measure—for example, have declined94 by more than a full standard deviation in the youngest generation of Americans; and according to one analysis, “patent creativity” has declined95 by over sixty percent since 1980. At the same time, Hollywood has become an uninspired junkyard of remakes, reruns, and sequels; while music,96 according to multiple studies,97is only becoming more homogenous and less complex.

Outside of the arts, entrepreneurship rates98 (as measured by the percentage of Americans who own part of a private company) have cratered—down by 50 percent across the board and down close to 70 percent for the college-educated class; culminating in last year’s first ever Forbes 30 Under 30 list devoid of a single self-made billionaire.99 Young Americans are also, according to data, less curious, less willing to disagree, and less likely to take risks.100, 101 One survey in particular, found that over a fifth102 of Americans can’t remember a single time they were curious about anything.

Boredom is the bureaucracy of consciousness—inefficient, cruel, and yet wholly indispensable.

The difficulty with all of it—with art, with business, with science—is that they require you to do the work; to think for yourself. Because anything original is, by definition, something no one else has thought of. In his 1984 book, Amusing Ourselves to Death, the media theorist Neil Postman argues that the modern age has not suppressed serious thought through censorship, but rather drowned it in entertainment. Unlike the print-based culture of the past, which encouraged rational discourse and deep engagement, television—and now, by extension, the digital attention economy—has reshaped public life into a spectacle, where politics, culture, and even personal reflection are subordinated to the demands of passive amusement. In a world where distraction is constant, consumption masquerades as contribution, while the actual labor of decision remains untouched, untended, and increasingly uncomfortable. As the authors of the electric shocks boredom study referenced earlier observed:

[a] reason why participants might have found thinking to be difficult is that they simultaneously had to be a “script writer” and an “experiencer;” that is, they had to choose a topic to think about (“I’ll focus on my upcoming summer vacation.”), decide what would happen (“Okay, I’ve arrived at the beach, I guess I’ll lie in the sun for a bit before going for a swim.”), and then mentally experience those actions.

From the perspective of natural selection, decisions are expensive103—and so cognitive effort, like physical effort, evolved to be minimized unless absolutely necessary, favoring instant rewards over delayed ones.104 It’s no wonder, then, that given the choice between deciding and being decided for, we choose the path of least resistance.

And in our haste to arrive—in the age of instant everything—we’ve erased the very gap that made getting there mean anything at all. Shortcuts save time, but they cost perspective. In other words, the faster we arrive at pleasure, the less it is felt. Without anything in-between, there is the same as here; and progress loses all definition. When the payoff is always now, we become stuck in a loop of instant gratification, unable to distinguish fleeting satisfaction from sustained reward. This, according to Bertrand Russell, is what drives the second paradox of boredom:

A boy or young man who has some serious constructive purpose will endure voluntarily a great deal of boredom if he finds that it is necessary by the way. But constructive purposes do not easily form themselves in a boy’s mind if he is living a life of distractions and dissipations, for in that case his thoughts will always be directed towards the next pleasure rather than towards the distant achievement.

In order to endure boredom, one must have a purpose—but in order to discover that purpose, one must first endure boredom. Put another way, the precondition for meaning is the willingness to be with its absence—because it arrives not when we want it, but instead appears when there’s nothing left to distract us. As the philosopher Martin Heidegger put it: “The nothing is what makes possible the openness of beings as such for [emergent awareness].”

That is to say, the openness we rush to fill—with stimulation, with pleasure, with clicks—is the only space where purpose, drive, creativity, even just basic decision-making can take root. It’s not what boredom gets you—it’s what it frees you from. You can’t force insight. You can’t download creativity. You must sit, watch, and then catch it—as it drifts through the open space of awareness—by paying attention.

From Einstein105 to Tolkien106 to Epictetus,107 the discipline of inaction—what German philosopher Siegfried Kracauer108 described as “radical boredom”—has been independently recognized, again and again, as the engine behind civilizational achievement. As the novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald explains it:

Boredom is not an end-product, [it] is comparatively rather an early stage in life and art. You’ve got to go by or past or through boredom, as through a filter, before the clear product emerges.

Boredom is the bureaucracy of consciousness—inefficient, cruel, and yet wholly indispensable. It’s where cognition churns, ideas are hazed, and the self, deprived of urgency, meanders through the subfloors of awareness—into serendipity.

What we’re escaping is everything else—depth, clarity, attention, the work of tolerating discomfort.

In recent years, psychologists and neuroscientists have begun to corroborate this ancient wisdom. A recent Nature109 publication showed that disrupting the brain’s Default Mode Network—the system active when the mind is unstimulated—significantly impaired “creative thinking,” limiting people’s ability to come up with novel or divergent ideas. Another experiment110 forced participants to copy numbers from a phone book—then asked them to list alternative uses for a pair of polystyrene cups. Compared to the non-bored control group, their minds wandered further—straying, stretching, and stumbling into more creative answers. But boredom does not just produce more creative ideas or higher-quality outcomes, it produces more—period.111 Much research reveals that individuals subjected to boredom generate more ideas, more solutions, more questions, more everything.112 In addition, there’s what psychologists call “autobiographical planning”—the future-oriented thinking that often accompanies mind-wandering. A 2011 study113 by Baird, Smallwood, and Schooler found that sensory-deprived participants spontaneously turned their attention toward long-term goals.

Darwin, famously, filled his idle afternoons with what he called “fool’s experiments.” He fed hair to plants.114 He played the bassoon for worms.115 He tested if caterpillars116 could taste color.117 It was boredom that carved out the space for such oddities—a sort of cognitive slack that lets deeper patterns emerge. As the poet William Blake put it: “The fool who persists in his folly will become wise.”

We think we’re escaping boredom by filling every silence, every pause, every flicker of inconvenience. But it’s the other way around. What we’re escaping is everything else—depth, clarity, attention, the work of tolerating discomfort. We were wired to find the world insufficient—but the system is flooded, and the thresholds are shot, and so the old machinery pings around, locked in a loop of false signals, burning the energy meant for effort on a feast of glittering garbage.