Decoding Espionage: Newly Declassified Documents Reveal the Secret Intelligence War

“Western powers can be in a cold war … before they realize it.” — CALDER WALTON, Spies: The Epic Intelligence War Between East and West

How is the history of espionage relevant to the present? How does recent document declassification change our understanding of the Cold War? Spies, Lies, and Algorithms broadly and concisely surveys the hows and whys of the U.S. intelligence community from multiple perspectives. Spies: The Epic Intelligence War Between East and West deeply surveys a century of espionage by Russia against the U.S. and Britain. Both books offer new information and conclude with sharp warnings for the present.

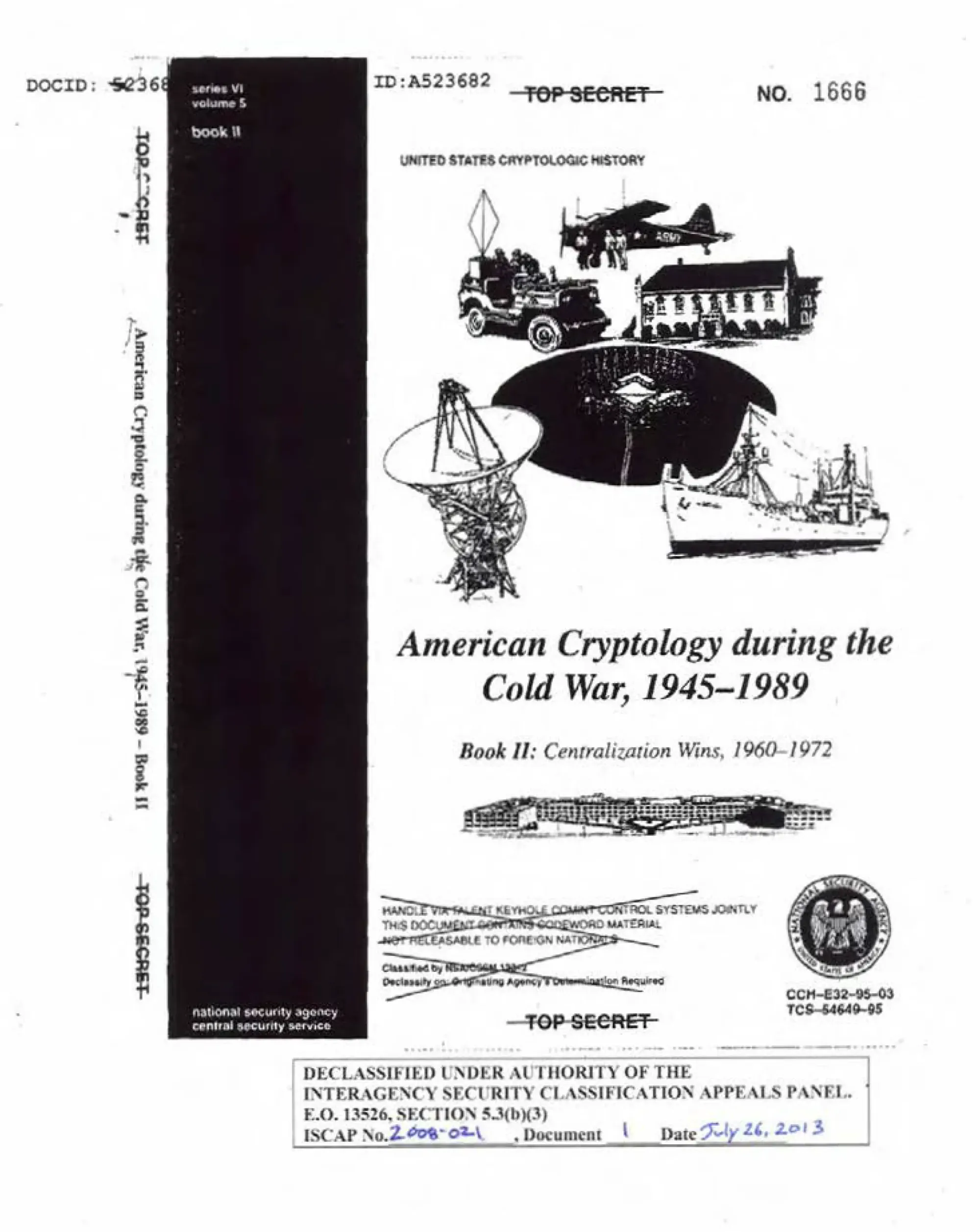

When I was in graduate school, the professor of a class on cold war history commented that a book he had initially assigned was already out of date just three years after its publication, due to information declassified in the interim. I recalled this often as I read, so many times, in Calder Walton’s Spies, that his sources were documents that had only been accessible or declassified as recently as 2022. As such, Walton’s book rewrites history, from Lenin to Putin. His thesis is that Russian espionage against the U.S. and Britain was as aggressive before and after the Cold War as it was during it.

Some of the book’s new or strengthened conclusions will please partisans on either side of political (U.S.) debates. Conservatives might find grim validation in the relentlessness and depth of Soviet—and then Russian—espionage. For example, Russian archives have not only proven the guilt of President Franklin Roosevelt’s advisers Lauchlin Currie and Treasury Secretary Harry Dexter White (among many others of the Cold War era), but also reveal compelling new evidence of Russian assistance to liberal politician Henry Wallace, as well as to later left-wing intellectuals and the multi-country antinuclear movement, and that the Soviet Union used détente (and later the Soviet Union’s collapse) to increase its espionage. Liberals, on the other hand, may be pleased by new evidence that U.S. Cold War policy did not take into consideration the Soviet perception of NATO, and that the founding U.S. Cold War document’s “domino theory” was based on a false premise (Kremlin documents now show that Soviets did not initiate wars in the Third World).

U.S. science and technology effectively drove both sides of the Cold War.

Newly released material also suggests that from Lenin to Putin, Russian leaders’ refusal to tolerate criticism and alternative points of view severely damaged the Soviet Union (and later Russia), both internally and externally. In contrast, the openness of the U.S. and Britain made it smart for Russia to focus its efforts on human spies. Walton points out, for an example perhaps of particular interest to Skeptic readers, that Russian spies in the U.S. were remarkably successful in their technological espionage, not just in accelerating the Russian development of the atomic bomb, but also more recently in stealing military technology, so that “U.S. science and technology effectively drove both sides of the Cold War.”

One revelation that startled me was new evidence that Truman was never briefed on Korea prior to the outbreak of war, and that, in Russia and the U.S., throughout the Cold War and since, most spies who were caught have been unmasked due to the opposing side’s defectors (and that both sides blundered in promoting people who committed treason). By contrast, Walton argues that, in most other areas, even intelligence historians continue to overemphasize the role of human spies and underestimate the role of communications interception (“signals intelligence”).

Zegart diagnoses the root of the problem as the necessity for secrecy: it is illegal for political scholars to examine most current intelligence.

One reason for the overemphasis on human spies highlighted by Professor Amy Zegart in Spies, Lies, and Algorithms is the explosion in popularity of spy entertainment in recent decades. The ticking time bomb scenario where the hero saves the world is a staple of fiction, but has vanishingly few analogs in real life, according to Zegart, where real intelligence work involves multiple sources being weighed against each other. (Walton’s most dramatic example of how both human and technological methods complement is new evidence of why President Kennedy was able to defuse the Cuban Missile Crisis.) However, this is not how things are portrayed in fiction. Zegart acknowledges how terrific it would be if fantasy were reality, and cites alarming evidence that the general public confuses the two. Her even more damning indictment is that entertainment has been mistaken for fact by senior policy makers in the 21st century, including by a U.S. Supreme Court Justice and in a confirmation hearing for a CIA director.

Zegart diagnoses the root of the problem as the necessity for secrecy: it is illegal for political scholars to examine most current intelligence, and older declassified documents sought by historians can arrive years after they’d been requested, and then only heavily redacted. Thus, Zegart finds it unsurprising that there are remarkably few articles about intelligence in academic journals, and incredibly few college courses on the history or politics of espionage. Zegart sees a similar dynamic at work when it comes to Congressional oversight, where elected representatives can’t talk about secret material.

To provide some much needed background, Zegart discusses the history of U.S. intelligence, including an additional chapter on highly placed traitors. The heart of the book is a chapter-by-chapter discussion of issues in the world of espionage. Real life intelligence work is mostly tedious and mundane. Her coverage of it, and what its results can and cannot do, is nuanced and sobering. Readers of Skeptic will not be surprised by the challenge of overcoming confirmation bias and human frailty at estimating size and probability. Evidence, she suggests, is that these are best overcome by an outsider “devil’s advocate” (a procedure bypassed in the case of Saddam Hussein’s alleged Weapons of Mass Destruction) type counterscenario planning. The paradox of presidential use of covert action analyzes why presidents of opposing views in different times and facing different challenges all criticize secret, morally questionable “active measures” but end up using them anyway.

Intelligence failures result from “the natural variations in the predictability of human events and the limitations of human cognition.” — AMY ZEGART, Spies, Lies, and Algorithms

Walton and Zegart agree that governments are losing their monopoly on intelligence gathering, essentially due to new technology. Zegart sees Google Earth, smart phones, and other public technology as having broken the monopoly that governments once had on the discovery of nuclear weapons sites and other military matters, and she discusses the potential dangers of premature revelation of that information, even if it is true. (Here and elsewhere, she emphasizes that the analysis of images and other data is a highly specialized and sophisticated skill learned by intelligence professionals, with many traps into which even well-meaning amateurs all to0 easily fall.) Where Zegart focuses on the activities of private citizens, Walton sees the future of intelligence being with multinational private companies, selling satellite access or high-end encryption programs to whatever government or business willing to pay their price, and so with no chance of government oversight.

Both books cite FBI statistics that document that China is by far the greatest threat to the U.S. through both government- and business-allied intelligence agencies sending over a seemingly endless number of highly trained agents to steal military and technological secrets from the U.S. Both authors also discuss the difficulty and urgency of reorienting an intelligence bureaucracy to new realities, Zegart’s being in greater depth and among the sources cited by Walton. Interestingly, both authors agree that history and current practice both indicate that intelligence is most effective when multiple techniques—human spying, satellite imagery, and much more—are used in combination, and both agree that cutting intelligence budgets ends up costing more than they save.

Both authors agree that cutting intelligence budgets ends up costing more than they save.

Both authors also discuss the relation between intelligence and conspiracy theories. First, both identify a few that were real, including the recent revelation of a Cold War deal with a leading manufacturer of government encoding machines. However, far more often people see conspiracies where none exist. Part of Walton’s data comes from England, and he suggests that “Those who tend to see … conspiracy overestimate the competency of those in Whitehall (home of British Secret Intelligence Service, MI6, much as ‘Langley’ is a term used for the American CIA).” Zegart quips that from her analysis of the impact of spytainment and her survey of Ivy League courses, students are more likely to hear a professor discuss U2 the rock band than the U-2 spy plane, one point of which is that ignorance of espionage history and practice is a great breeding ground for conspiracy theories. While Stalin’s paranoia is well known, Walton provides evidence of Lenin’s as well, and concludes that Putin is “a naturally inclined conspiracist.” (Note that Putin began his career in counterintelligence—ferreting out spies.)

As outstanding as both books are, no text of such depth can be perfect. The most serious problem with Walton’s Spies is that the bibliography is solely online (and often inaccessible), and the entries on it do not always include dates and publisher information. In the book itself, if part of Walton’s thesis is that the Cold War started in 1917, shouldn’t he have offered more than one example of early espionage? Recent scholarship in most areas is thorough (based on the endnotes), but some important books are missing, including G-Man by Beverly Gage (for its new data about the FBI’s work abroad [which it is not supposed to do], and which I reviewed in Skeptic).

Most of Walton’s 548 pages of main text are well used, but some ancillary material (such as recently declassified World War II British intelligence work unrelated to Russia) might have been edited out for length, however fascinating and new it is. I also wonder if, in a history book, it is best practice for an author to explicitly discuss implications for the present, which he does, with several opening pages on Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine and a closing chapter on the relevance of the book’s conclusions to 21st century Chinese espionage. That said, this is telling, or at least amusing: for this book, it was discovered that a World War II Russian operative in Ukraine was named Nikita Khrushchev, who might not have gone on to become a future Soviet leader had he tried to warn Stalin about German troops massing on the border of Russia. Another likely case of the futility of speaking truth to power in the old Soviet bloc is the anecdote about a lone non-Communist Czech minister, Jan Masaryk, who tried to warn the public about Soviet tyranny and soon died from falling out a window, allegedly from suicide.

Walton offers two examples of recent or new evidence that the world came closer to nuclear war than previously known.

More to the point, Walton offers two examples of recent or new evidence that the world came closer to nuclear war than previously known in not only the Cuban Missile Crisis, but, possibly, also in a 1980s military exercise that may have been mistaken for the real thing. Both resulted in increased dialogue between the U.S. and Russia.

The two books are masterclasses on their respective subjects. Walton doesn’t just incorporate recent research on Soviet Russian espionage, but he has investigated original documents (some declassified very recently) in Russia, Ukraine (for its intelligence about the Soviet Union), Britain, the U.S., and elsewhere. In addition to Zegart’s original research and government work, she has mastered a vast secondary literature and demonstrates her experience in explaining it. Both can be read by skeptics for evidence of the very real dangers posed by confirmation bias and lack of critical thinking by the highest government officials, as well as by the general public who, at least in some countries, empower them.