Iranians Are Rejecting Theocracy: The Islamic Republic’s Unintended Legacy

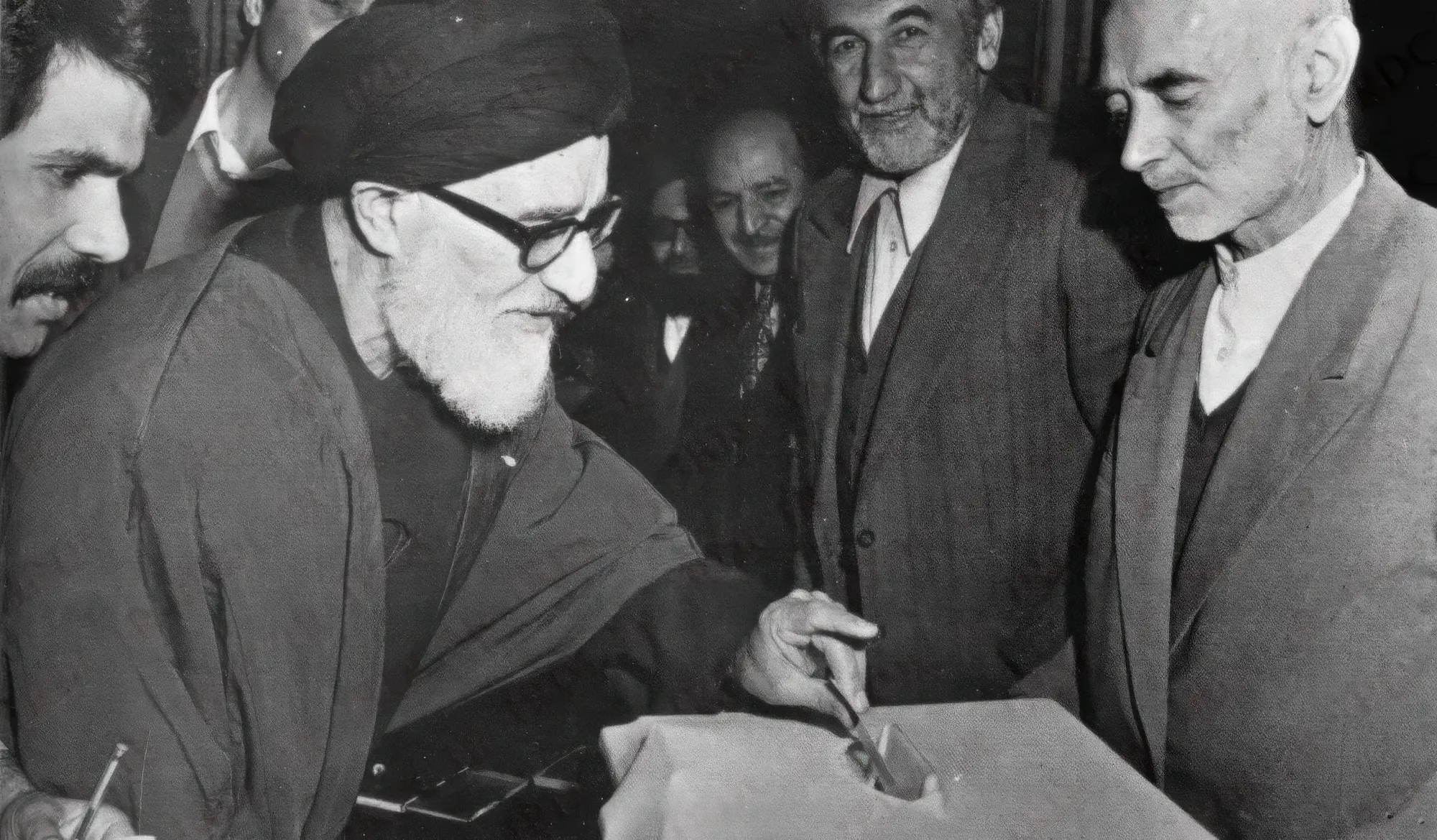

The Vote

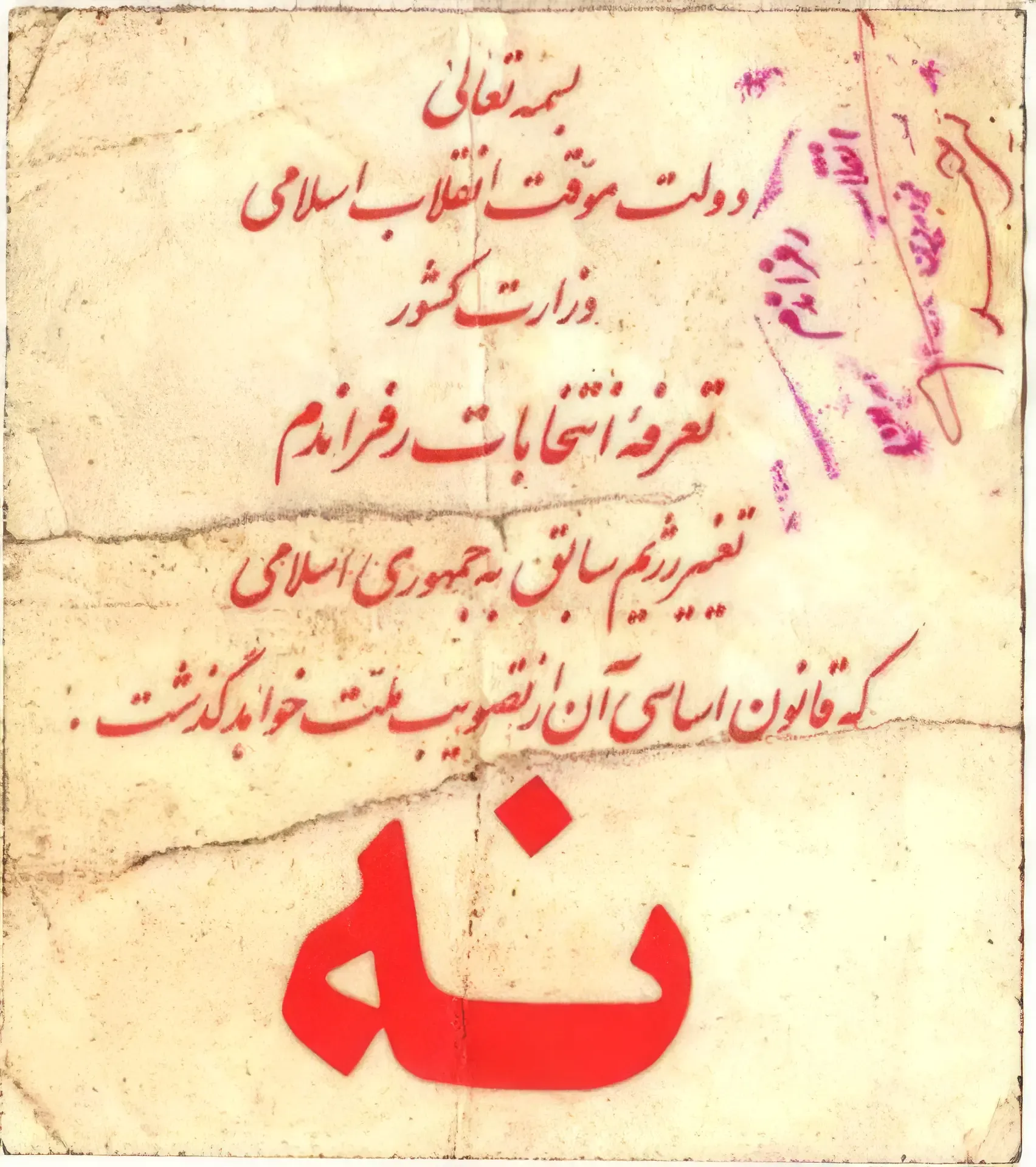

On March 30–31, 1979, Iranians went to the polls. The ballot contained a single question: Should Iran become an Islamic Republic? The choices were “Yes” (Green) or “No” (Red). The official result: 98.2% voted Yes.1

Fifty-Eight Days Earlier

On February 1, 1979, Ayatollah Khomeini returned to Iran after fourteen years in exile. Millions filled the streets of Tehran—the estimates range from two to five million.2 But the man they cheered was a carefully constructed image. During the flight, Khomeini remained secluded in the upper deck of the chartered Boeing 747, praying.3 When the plane landed, he chose to be helped down the stairs by the French pilot rather than his Iranian aides, a calculated move to prevent any subordinate from sharing the spotlight.4

He chose his first destination deliberately: Tehran’s main cemetery, where those who died during the revolution were buried. The crowd was so dense his motorcade could not pass; he took a helicopter instead.5 By speaking among the graves, Khomeini positioned himself as the guardian of those who died in the revolution and as someone who would fulfill what they had sacrificed for.

In the weeks that followed, Khomeini offered both material goods and spiritual salvation. He promised free electricity, free water, and housing for every family. Then he added the caveat that would define the coming era: “Do not be appeased by just that. We will magnify your spirituality and your spirits.”6

A Coalition of Contradictions

The crowd that greeted him was not a monolith, but a coalition of contradictions. Marxists marched hoping for a socialist future free of American influence. Nationalists and liberals sought constitutional democracy. The devout sought governance by Sharia—and for them, the revolution was holy war: the Shah represented taghut, the Quranic term for tyrannical powers that lead people from God, and those who died fighting him became shahid, martyrs.

Khomeini managed these competing visions by keeping his actual plans vague. He spoke of freedom, justice, and independence, terms each faction could interpret as it wished.7 His blueprint for clerical rule, Velayat-e Faqih, remained in the background. Abolhassan Bani-Sadr, who would become the Islamic Republic’s first president, later recalled: “When we were in France, everything we said to him he embraced and then announced it like Quranic verses without any hesitation. We were sure that a religious leader was committing himself.”8 Khomeini himself would later state: “The fact that I have said something does not mean that I should be bound by my word.”9

The Empty Phrase

Now, let’s return to the ballot.

A republic places sovereignty in the people. Citizens choose their laws. An Islamic state places sovereignty in God, but not “God” in some abstract, philosophical sense. The God of the Islamic Republic is specifically Allah as understood in Shia Islam: a God who communicates through the Quran, whose will was interpreted by the Prophet Muhammad, then by the twelve Imams, and now (in the absence of the hidden Twelfth Imam) by qualified Islamic jurists. This is not a deist clockmaker or a personal spiritual presence. This is a God with specific laws, specific requirements, and specific men authorized to speak on His behalf.

So, what did God want? The ballot never said.

“Islamic Republic” contained no details. No constitution, no enumerated rights, no definition of which Islamic laws would apply or who would interpret them. Voters were not choosing a specific system of government. They were choosing a phrase, and trusting that its meaning would be filled in later by men they believed spoke for God.

For those paying attention, there were clues. Khomeini had written extensively about Velayat-e Faqih (the Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist) a system in which a senior cleric would hold supreme authority as God’s representative on Earth. He had lectured on it in Najaf. He had published a book.10 But in the noise of revolution, in the flood of promises about free electricity and spiritual elevation, these details were background static. The crowds were not voting on constitutional theory. They were voting on hope.

The 98% voted Yes. Forty-seven years later, we can measure what exists in Iranian society.

Religious Faith

For this case study to be valid, we must establish a baseline. Was Iranian society already irreligious before 1979, or has religiosity declined under the theocracy?

Available evidence suggests the latter.

In 1975, a survey of Iranian attitudes found over 80% of respondents observing daily prayers and fasting during Ramadan. The methodology is not fully documented in accessible sources.11 However, the broader historical record supports the baseline: the 1979 revolution mobilized millions under explicitly Islamic banners, clerical figures commanded genuine social authority, and the Iranian government’s own 2023 leaked survey found 85% of respondents saying society has become lessreligious than it was.12 Forty-seven years later, mosques are empty.

Official Iranian census data reports 99.5% of the population as Muslim.13 This figure measures legal status, not belief. Under Iranian law, a child born to a Muslim father is automatically registered as Muslim, and leaving Islam carries severe legal consequences. While formal executions for “apostasy” are relatively rare—the regime prefers to charge dissidents with crimes like “Enmity against God” or “Insulting the Prophet”—the threat is sufficient to enforce public silence.

In June 2020, the Group for Analyzing and Measuring Attitudes in Iran (GAMAAN) surveyed over 50,000 respondents using methods designed to protect anonymity.14

Results:

- 32.2% identified as Shia Muslim

- 22.2% selected “None”

- 8.8% identified as Atheist

- 7.7% identified as Zoroastrian

- 5.8% identified as Agnostic

- 1.5% identified as Christian

While this online sample skews urban (93.6% vs. Iran’s 79%) and university-educated (85.4% vs. 27.7% nationally), the magnitude of divergence from official statistics—32% Shia vs. 99.5% in census data—is too large to explain through sampling bias alone. Meanwhile, face-to-face surveys suffer the opposite problem: when GAMAAN asked respondents if they’d answer sensitive questions honestly over the phone, 40% said no.15

An interesting outcome of this study is that Iran has approximately only 25,000 practicing Zoroastrians (the total population of Iran is around 92.5 million), yet 7.7% selected this identity. Researchers interpret this as “performing alternative identity aspirations”—claiming pre-Islamic Persian heritage to reject imposed Islamic identity.16

The key findings are, however, clear: 44.5% selected a non-Islamic category when asked their current religion and 47% reported transitioning from religious to non-religious during their lifetime.

The second figure suggests active deconversion rather than inherited secularism.

In 2024, a classified survey by Iran’s Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance (conducted in 2023) was leaked to foreign media.17 This data provides a comparison point from within the regime itself.

|

Indicator |

2015 |

2023 |

|

Support separating religion from state |

30.7% |

72.9% |

|

Pray “always” or “most of the time” |

78.5% |

54.8% |

|

Never pray |

3.1% |

22.2% |

|

Never fast during Ramadan |

5.1% |

27.4% |

The same survey found 85% of respondents said Iranian society had become less religious in the previous five years. Only 25% reported trusting clerics.

Based on my years of closely following Iranian society, the pace of religious abandonment has accelerated significantly since the 2022 “Woman, Life, Freedom” uprising. The leaked government data confirms this trajectory: the sharpest shifts in prayer and fasting occurred within the 2015–2023 window, with 85% saying society had grown less religious in just the previous five years.

In February 2023, senior cleric Mohammad Abolghassem Doulabi stated that 50,000 of Iran’s approximately 75,000 mosques had closed due to low attendance, a claim partially corroborated by the leaked government survey finding only 11% always attend congregational prayers.18

Election participation has also declined. Official turnout in the June 2024 presidential election was 39.93%, the lowest in the Islamic Republic’s history.19

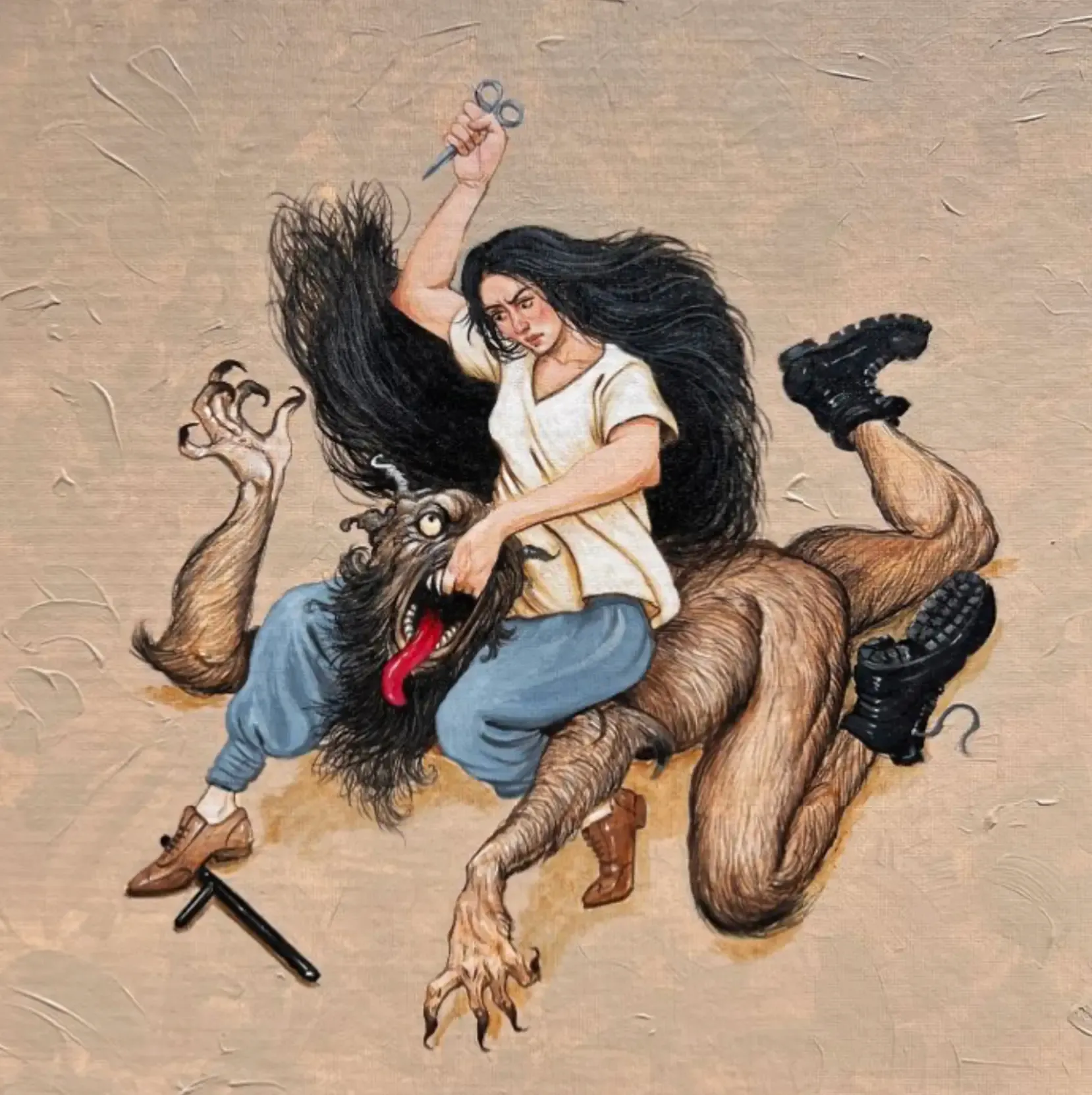

The Evidence on the Streets

The data on paper is corroborated by the specific vocabulary of the street. The protest chants have evolved from requesting reform to rejecting the entire theological framework.

Consider the chant: “Neither Gaza nor Lebanon, I sacrifice my life for Iran.”

This is a direct rejection of the regime’s core ideology. The Islamic Republic prioritizes the Ummah—the transnational community of believers—over the nation-state. By rejecting funding for Hamas and Hezbollah in favor of national interests, protesters are secularizing their priorities: the Nation has replaced the Faith as the object of ultimate concern.

Even more specific is the chant: “Death to the principle of Velayat-e Faqih.”

The protestors are not merely calling for the death of the dictator (Khamenei); they are targeting the specific theological doctrine that grants him legitimacy. They are rejecting the very concept of divine guardianship.

But the most striking evidence of the revolution’s failure is the return of the name it sought to erase. In a historical irony that defies all prediction, crowds now chant “Reza Shah, bless your soul,” and call upon Reza Pahlavi, the son of the deposed Shah, to return. The same population that staged a revolution to overthrow a monarchy in 1979 is now invoking that monarchy as the antidote to theocracy.

The Mechanism

A note on terminology: When this article refers to “Allah,” it means the legislative deity of the Islamic Republic—a God with enforceable commands interpreted by authorized clerics. This is distinct from the personal God that 78% of Iranians still believe in.

As mentioned earlier, Iran’s constitution establishes Velayat-e Faqih—the Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist. Article 5 declares that in the absence of the Twelfth Imam (a messianic figure believed to have been in supernatural hiding since the 9th century), authority belongs to a qualified jurist. The Tony Blair Institute’s analysis states it directly: “the supreme leader’s mandate to rule over the population derives from God.”20 Khamenei’s own representative, Mojtaba Zolnour, declared in 2009: “In the Islamic system, the office and legitimacy of the Supreme Leader comes from God, the Prophet and the Shia Imams, and it is not the people who give legitimacy to the Supreme Leader.”21

This is not metaphor. The system’s legitimacy rests on the claim that its laws are Allah’s laws, its punishments are Allah’s punishments, its wars are Allah’s wars.

When morality police detained Mahsa Amini, leading to her death, they were enforcing the mandatory religious duty of “Forbidding the Wrong.” When courts execute apostates, they enforce Allah’s law. When the regime sends billions to Hezbollah while Iranians face poverty, it pursues Allah’s mission. When it pursues a nuclear program that invites crushing sanctions, it frames the resulting economic ruin not as policy failure, but as a holy “Resistance” against the enemies of Islam. Every act of misrule carries Allah’s signature.

Khorramabad, Iran, January 8, 2026: Protesters raise the pre-1979 lion-and-sun flag, described as a symbol of secular restoration, atop a statue of the Ayatollah. (Source: Press Office of Reza Pahlavi)

In a secular dictatorship, citizens can hate the dictator while preserving their faith. The North Korean who despises Kim Jong-un can still pray. But in a theocracy, the oppressor and God speak with one voice. To oppose the oppressor is to oppose God. To want freedom is to reject divine authority.

The regime created conditions where, for many, opposing political authority became entangled with questioning religious authority.

The Psychology of Religious Rebellion

Jack Brehm’s reactance theory (1966) demonstrates that when people perceive threats to their freedom, they become motivated to restore it, often by embracing the forbidden alternative.22 Subsequent research has applied this specifically to religion. Roubroeks, Van Berkum, and Jonas (2020) found that restrictive religious regulations can trigger reactance that leads to both heresy (holding beliefs contrary to orthodoxy) and apostasy (renouncing religious affiliation entirely).23

The critical insight: In cases of psychological reactance, the emotional pushback against coercion often precedes the intellectual dismantling of the belief system.

The sequence is rarely a straight line, but the components are clear:

- Coercion: The lived experience of religious enforcement

- Dissonance: The widening gap between the regime’s claims of divine justice and the reality of corruption and violence

- Access: The internet provides a “vocabulary of dissent”

This third point is crucial. Iran’s internet users grew from 615,000 in 2000 to over 70 million today.24 Despite billions spent on censorship, officials admit 80–90% of Iranians use VPNs, which allow to circumvent restrictions by changing the user’s internet location to that of another country.25

For the intellectually curious, the internet offered arguments against Islamic theology that were previously banned. But for the average citizen, it offered something perhaps more powerful: validation. It showed them that their anger was shared. It broke the “pluralistic ignorance,” the state where everyone privately rejects the norm but publicly conforms because they think they are the only ones.

Whether through deep study or simple emotional exhaustion, the result was the same: the breaking of the psychological bond between the citizen and the faith.

The Unintended Outcome

Iran’s religious decline is among the fastest documented in modern history. Stolz et al. (2025) in Nature Communications established that Europe’s secular transition took approximately 250 years. Iran’s comparable shift from over 80% observing daily prayers in 1975 to 47% reporting lifetime deconversion by 2020 occurred in roughly 45 years. Pew’s global data shows Muslim retention rates averaging 99% across surveyed countries.26

However, Europe secularized without internet or satellite television. Iran’s shift occurred alongside a 90-fold increase in internet access. Theocracy may provide the motive for questioning imposed faith; technology provides the accelerant that compresses generational change into decades. Ex-Muslim testimonies, apostasy narratives, ordinary lives lived without faith—these demonstrated that abandoning religion was survivable. The forbidden became imaginable. Others found arguments that validated what they already felt. The reasoning matched the shape of their anger, and that was enough.

For forty-seven years, the Islamic Republic worked to manufacture belief. Mandatory religious education from childhood. State control of media. Morality police enforcing dress and behavior. Apostasy punishable by death. A constitution grounding all authority in God. They did not leave this to chance.

The data suggests it did not work.