The Future Leaks Out: William S. Burroughs’s Cut-Ups and Cucumbers

William S. Burroughs was one of the most controversial literary figures of the early 1960s, an American postmodern author and visual artist who was considered one of the key figures of the Beat Generation that influenced pop culture (he was friends with Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac). He also became preoccupied by an unusual experiment: the cut-up, a technique in which a written text is cut up and rearranged to create a new text. But this was no mere artistic preoccupation. Burroughs, author of the notorious Naked Lunch (the subject of a major literary censorship case when its publisher was sued for violating a Massachusetts obscenity law) claimed to have found a sort of window into the future, a time warp on paper and on tape.

Burroughs got the cut-up idea in 1959 from his close friend Brion Gysin. Burroughs remembered, “It was simply of course applying the montage method, which was really rather old hat in painting at that time, to writing. As Brion said, writing is fifty years behind painting.”1 Burroughs traced the cut-up back to an incident from the Dada movement of the 1920s, when Tristan Tzara announced his intention to create a poem on the spot by pulling words out of a hat.2

For Burroughs, however, the cut-ups were something more than a creative writing technique. He traced this supposed revelation back to a Time magazine article by the oil industrialist John Paul Getty. (Burroughs may have been referring to a February 1958 Time cover story on Getty. Getty did not write the article.) Upon cutting up the article, Burroughs created the following phrase: “It’s a bad thing to sue your own father.” When Getty was in fact sued by one of his sons, Burroughs came to believe that his cut-up had foretold the future:

Perhaps events are pre-written and prerecorded and when you cut word lines the future leaks out. I have seen enough examples to convince me that the cut-ups are a basic key to the nature and function of words.3

Years later, in Howard Brookner’s Burroughs, the fedora-clad, now-aged author explains to his poet friend Allen Ginsberg:

Every particle of this universe contains the whole of the universe. You yourself have the whole of the universe. If I cut you up in a certain way I cut up the universe … So in my cut-ups I was attempting to tamper with the basic pre-recordings. But I think I have succeeded to some modest extent.

At this, Ginsberg could only nod and utter a number of noncommittal “um hmms,” adding later: “Burroughs was, in cutting up, creating gaps in space and time, as Cezanne, or as meditation does.” Burroughs also cited a dubious summary of Wittgenstein’s Paradox: “This is Wittgenstein: If you have a prerecorded universe, in which everything is prerecorded, the only thing that is not prerecorded are the prerecordings themselves.”4 The actual Wittgenstein’s Paradox holds that “no course of action could be determined by a rule, because any course of action can be made out to accord with the rule.”

Ludwig Wittgenstein was a philosopher and language theorist, but there is no reason to believe that he thought of the universe as a giant tape recording. Rather, Burroughs’s notion of human consciousness was clearly influenced by L. Ron Hubbard’s engram theory, itself reliant on Freudian psychoanalytic theory with its emphasis on trauma and repressed memory. Seemingly derived from the medical theory of the memory trace, Hubbard described engrams as imprints of unpleasant experiences on the protoplasm of living beings.

Burroughs went so far as to describe the cut-up method as “streamlining Dianetics therapy system.” Proposing that his tape method could be used for therapy, he went on to suggest wiping “traumatic material” off a magnetic tape.5 He even hinted that Hubbard had borrowed the tape recording idea from him! His friend Ian Sommerville sold Hubbard two recorders, and Burroughs seemed to find it significant that Sommerville had become sick soon after, as if Hubbard were using an insidious black magic.6 Burroughs began to see the Scientology system as a form of brainwashing, even as he was increasingly convinced of Hubbard’s theories.

Moving on to the world of cinema, Burroughs made two cut-up films, Towers Open Fire in 1963 and The Cut-Ups in 1966, with the help of producer Antony Balch. And, in 1965, Burroughs proposed to Balch “a new type of science fiction film,”7 one that would expose “the story of Scientology and their attempt to take over this planet.”8 The film would explain that “vulgar stupid second rate people” had taken over the planet by means of a “virus parasite.”9

Burroughs brazenly went ahead with his cut up experiment, even though it might have serious ramifications for the universe: “Could you, by cutting up … cut and nullify the pre-recordings of your own future? Could the whole prerecorded future of the universe be prerecorded or altered? I don’t know. Let’s see.” Perhaps he was thinking of the scientists at Los Alamos, who exploded the first atomic bomb without being completely sure of the ramifications.10

Nor was Burroughs’s “sample operation” in influencing the universe an especially ethical exercise. In fall 1972 the author took issue with the Moka, “London’s first espresso bar,” leading to a vengeful exercise with overtones of Maya Deren, the experimental filmmaker who was also a voodoo priestess and flinger of malicious hexes.

Burroughs’s grudge against the Moka arose over what he described as “unprovoked discourtesy and poisonous cheesecake.” He took a movie camera and began filming. Within two months, the bar was closed. Burroughs recommended using this exercise to “discommode or destroy” any business you did not particularly like. He did not consider the bar might have shut down for some unrelated reason. Maybe word got out about the bad cheesecake.11 Some of the author’s magical thinking in this period may be a result of reliance on drugs, but Burroughs was a believer in curses since childhood.12

It is perhaps not a surprise that some thought the author’s new method was a prank. At a 1962 Edinburgh festival, Burroughs spoke about his new technique, which he was then calling the fold-in method. Members of the crowd thought they were being pranked, causing an Indian author to ask, “Are you being serious?” Burroughs insisted that he was.13

Burroughs presented a summary of his method to a gathering of students at Colorado’s Naropa Institute in 1976, and part of this lecture can be heard on the record Break Through in Grey Room. When Burroughs describes the revelatory Getty cut-up, laughter can be heard from the audience. Perhaps sensing some skepticism, Burroughs insists on his innocence in constructing the Getty rewording: “I mean, it’s purely extraneous information to me. [A woman can be heard laughing.] I had nothing to gain on either side. We had no explanation for this at the time, it’s just suggesting, perhaps, that when you cut into the present the future leaks out.”14

Burroughs may have been a bit disingenuous in telling the Naropa students he had no relationship to the wealthy Getty family. In the mid-1960s, in fact, through the art dealer Robert Fraser, Burroughs mingled with John Paul Getty Jr.15 Then, Burroughs stayed at a flat owned by art dealer Bill Willis from March to July 1967, where he often saw the likes of Getty, Jr.16

Admittedly this would have been later than Burroughs’s initial Getty cut-up (apparently in 1959, when Burroughs first became immersed in the whole cut-up process). But Burroughs may have been acquainted with members of the Getty circle before he actually met the Getty family. Plus, we are relying on a version of events that Burroughs publicly recounted in Daniel Odier’s The Job and later in 1976, and relying on Burroughs’s perception is a dubious proposition. In the 1976 Naropa lecture, Burroughs claims the lawsuit occurred a year after his cut-up,17 while in Daniel Odier’s The Job he claims it was a three-year gap. Also, in The Job he seems to garble matters by conflating the magazine title—Time—with the name of Getty’s company—Tidewater.18 I have not found any record of Getty being sued by one of his sons during the time period described.

Burroughs’s literary acquaintances were not impressed to see the author seemingly risking his (still quite tenuous) literary reputation on an obsession like this. Samuel Beckett was appalled at the notion of using the words of other writers and said so to Burroughs directly: “That’s not writing. It’s plumbing.”19 The poet Gregory Corso told Burroughs the cut-up method would quickly become “redundant.”20 Novelist Paul Bowles felt the method would “alienate the reader.”21 Norman Mailer was the most prominent literary figure to champion Burroughs’s work to the American mainstream, and he must have been let down to see Burroughs abandoning a major writing career to get hung up on something Mailer probably considered a trivial sidetrack. To Mailer, the cut-up experiments were a mere “recording,” a distraction from the art of fiction.22 Jennie Skerl and Robin Lydenberg note that “positive assessments of Burroughs’s cut-ups were rare … most saw cut-ups as boring or repellent.”23

Nevertheless, Burroughs produced his “cut-up trilogy”: The Soft Machine (1961), The Ticket That Exploded (1962), and Nova Express (1964), although none sold as well as Naked Lunch. Biographer Ted Morgan calls them “inaccessible to the general reader.”24 The impenetrability of Burroughs’s cut-ups added to his reputation as a “difficult” author. Even Burroughs’s off-and-on friend Timothy Leary asked, rhetorically, “Do you actually know anyone who has finished an entire book by Bill Burroughs?”25

Burroughs was greatly impressed by the 1971 English-language publication of Konstantin Raudive’s Breakthrough: An Amazing Experiment in Electronic Communication with the Dead, which popularized what is known today as EVP (Electronic Voice Phenomenon), a widely discredited phenomenon that purports to find hidden messages in audio recordings of background noise, of recordings played backwards, in random static noise between radio stations, and other low information sources.

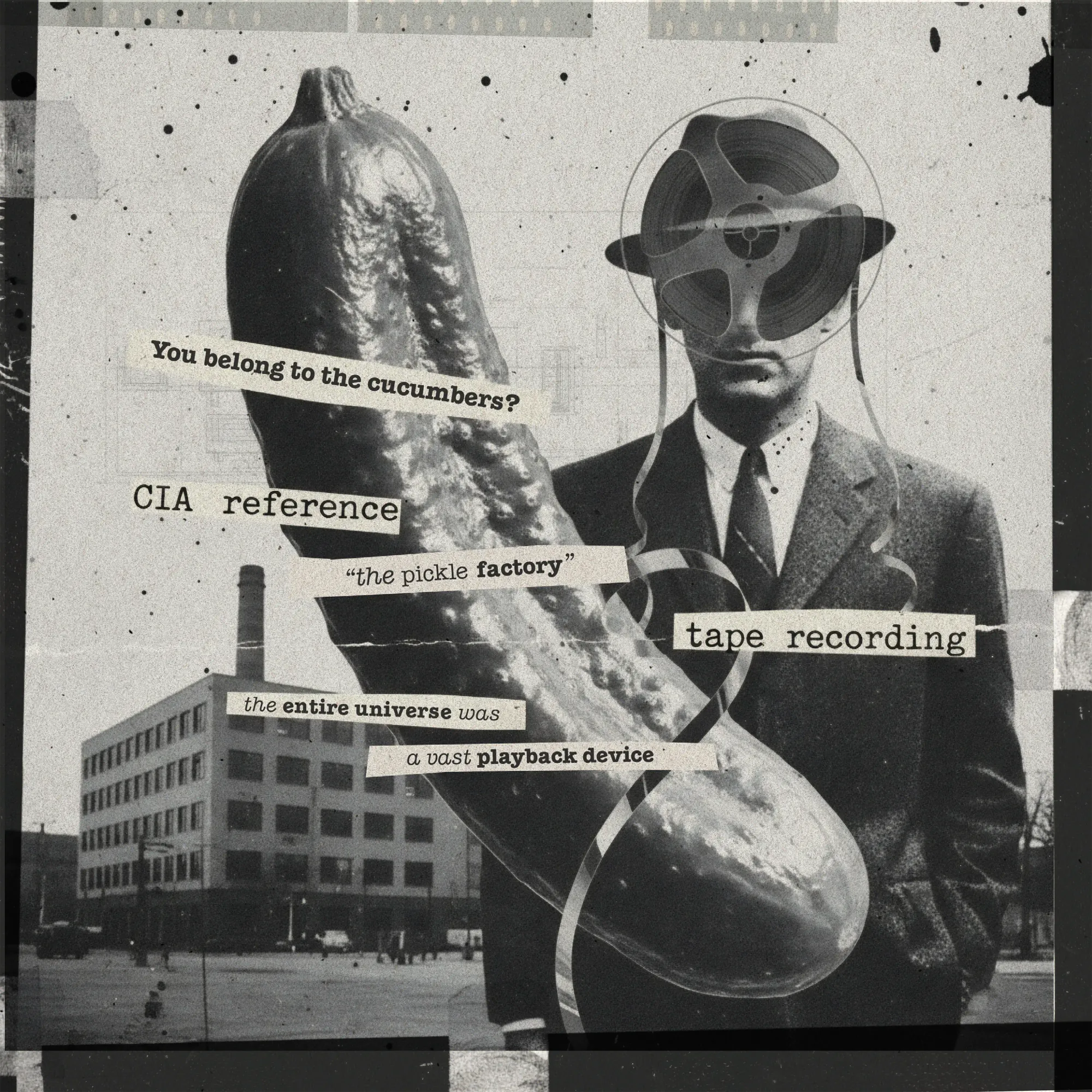

Raudive believed these were the voices of the dead. Burroughs offered his own theory in keeping with his cut-up cosmology, namely that the entire universe was a vast playback device, something akin to a tape recording. Inspired by Raudive (and no doubt, Hubbard), Burroughs boldly rejected the precepts of modern psychology. People suffering from schizophrenia were not experiencing hallucinations; they were “tuning in to an intergalactic network of voices.”26

If we look at Burroughs’s supposed predictive phrases, we see a lot of what can only be called “reaching” or grasping at straws. In 1964 Burroughs came up with the phrase, “And here is a horrid air conditioner.” Ten years later, he “moved into a loft with a broken air conditioner.”27 There is nothing mysterious about having an air conditioner break down. If anything, Burroughs was lucky if he went ten years without a broken air conditioner.

Then there was this cryptic recorded query of Raudive’s: “Are you without jewels?” To Burroughs, this must refer to lasers, “which are made with jewels.” And another especially absurd quote from Raudive’s recordings: “You belong to the cucumbers?” Burroughs had read that “the pickle factory” was a slang term for the CIA, so the recording seemed to be an obvious CIA reference. He read this in either Time or Newsweek. For an icon of bohemian literature, one could argue that Burroughs relied an awful lot on the mainstream media for his prognostications.28 But how were researchers like Raudive and Burroughs tapping into the playback of the universe? Burroughs himself asked this question:

Now how random is random? We know so much that we don’t consciously know that perhaps the cut-in was not random. The operator at some level knew just where he was cutting in. As you know exactly on some level exactly where you were and what you were doing ten years ago at this particular time.29

Burroughs was admitting that the cutter was influencing the cut-up, but he believed this was because the cutter was unconsciously tuned in to the future. A simpler explanation would be that Burroughs convinced himself that he was doing random work while he was in fact cutting together semiconscious rephrasings. For instance, he may have heard a rumor from one of his monied acquaintances that one of Getty’s sons was considering a legal action well before actually suing.

If the experimenter (i.e., Burroughs, or Gysin, or Raudive) is unconsciously influencing the experiment, then what we have is a new version of the Ouija board with its self-guided planchette—a device whose movements and messages are created by users who come to believe they are receiving messages from a spirit or other mysterious entity when, in fact, they are moving the planchette. This is known as the ideomotor response.

It is worth noting that in this lecture Burroughs refers to a number of concepts that are often considered dubious today, such as repressed memories and unreliable eyewitness accounts of events. For instance, he discusses “freaks,” seemingly referring to individuals with alleged eidetic or “photographic” memory. Perhaps he was thinking of his late friend Jack Kerouac, who was known by some in Lowell, Massachusetts, as “Memory Babe” due to his purportedly freakish recall powers?

There is no evidence to support the notion that anyone can foretell the future by cutting up newspapers, books, or film footage.

Burroughs’s countercultural reputation grew through the 1970s until his death in 1997. But his cut-ups don’t seem to have received much attention from the parapsychological community, perhaps because he was so preoccupied with now-dated media and technology: newspapers, reel-to-reel recordings, and 8mm film. His metaphysical notion of the universe as a “playback” machine seems dated next to the trendier notion of the universe as a computer matrix.

William Burroughs was one of the most fascinating (and darkly funny) literary figures of the twentieth century, but that doesn’t make him a scientist. There is no evidence to support the notion that anyone can foretell the future by cutting up newspapers, books, or film footage.