Who’s Crazy Now? DSM-5 and the Classification of Mental Disorders

What does it mean to be crazy? We use the word loosely. In casual conversation we might say “He’s crazy” or “That’s insane!” but that doesn’t mean we really think the person is certifiable. Sometimes all it means is “He doesn’t agree with me.” What does it take to be formally diagnosed with a mental illness?

Medical diagnoses like broken bones and diabetes are pretty straightforward. They depend on objective findings from diagnostic tests, but diagnosis of mental disorders is mostly subjective. There’s no blood test for schizophrenia. Psychiatry is arguably the least evidence-based of all the medical specialties.

Mental health diagnosis is guided by rules. The problem is that the rules keep changing. A person who’s crazy now might not be considered crazy in 2050. A person who’s considered sane today might have been locked up in an insane asylum in 1850. So, who’s crazy now, and how do we decide?

Even psychiatrists are not very good at knowing whether a patient is crazy. In 1973, Robert Rosenhan published the study in Science called “On Being Sane in Insane Places” that became an instant classic in psychiatry lore (read the full text here or here). Fake patients got themselves admitted to 12 different psychiatric hospitals by briefly claiming to have auditory hallucinations; once admitted, they acted normally and said they no longer heard voices. Every one of them was diagnosed with schizophrenia and they were kept in the hospital an average of 19 days. In order to get released, they were forced to admit to having a mental illness, and forced to take antipsychotic drugs.

In a follow-up, the hospitals challenged Rosenhans to send them more fake patients and promised to detect them. They identified 41 potential fakes out of the subsequent 193 new patient admissions, but in fact Rosenhan had not sent them any fake patients. He had documented that the confirmation bias was at work: Being bored, one fake patient had started a diary. Rosenhan noted how that was interpreted by the staff: “And given that he is disturbed, continuous writing must be behavioral manifestation of that disturbance, perhaps a subset of the compulsive behaviors that are sometimes correlated with schizophrenia.”

American mental health professionals diagnose patients according to a book titled the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). But studies like Rosenhan’s show that even with a manual to go by, diagnosis is far from reliable. And the diagnoses in the DSM change with every new edition. In 1952 homosexuality was a mental illness, but by 1974 it no longer was. How could the abnormal become normal in two decades? Is the DSM based more on culture than on evidence?

Before we had diagnostic standards, psychiatry was a mess. There was no consistency in diagnosis. Mental illness was attributed to fanciful causes. Hysteria was caused by a wandering womb: the uterus somehow became untethered from the pelvis and went on a walkabout around the body. The word lunatic was derived from the Moon, which supposedly caused epilepsy and madness. People used to be diagnosed with neurasthenia, a physical “weakness of the nerves.”

And psychiatric diagnoses were used to control people. Fugitive slaves were diagnosed with drapetomania (they’d have to be crazy to run away, right?). The bogus diagnosis of “sluggish schizophrenia” was invented in the USSR as an excuse to institutionalize political dissidents. The thinking was that dissidents must be crazy because why else would they oppose the best system of government in the world? Husbands could get rid of wives by having them institutionalized at the sole discretion of the institution’s superintendent for complaints like “does not do her housework.” There’s a wonderful story by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, “The Yellow Wallpaper,” that illustrates the oppression of women by men in a pre-feminist era. The narrator’s misguided physician husband insists on treating her depression by locking her up for a draconian “rest cure;” the forced inactivity and lack of stimulation ended up driving her insane.

Precursors of the DSM

In the 1840 Census, census takers recorded a single category of idiocy/insanity. In some towns, all the African Americans were marked down as insane! In 1888 Frederick Wines wrote a “Report on the defective, dependent, and delinquent classes of the U.S.” He recognized seven categories, several of which were medical (not mental) disorders:

Dementia; Dipsomania (uncontrollable craving for alcohol); Epilepsy; Mania; Melancholia; Monomania; Paresis.

The real impetus for classifying mental disorders was the need to collect statistical information. In 1918, a Statistical Manual for the Use of Institutions for the Insane was created. It recognized 22 categories, mostly psychoses like psychosis with syphilis, psychosis with brain tumor, etc. Its two final categories were undiagnosed psychoses and not insane.

The DSM Is Born

In World War II, psychiatrists were involved in the selection of recruits and treatment of soldiers, and the Army developed its own classification scheme. This spurred the American Medico-Psychological Association to form a committee that developed the first DSM.

Diagnoses have multiplied with successive revisions of the DSM, from 106 disorders in the 1952 version, DSM-I, to 600 discrete diagnoses (counting modifiers) in the 2013 DSM-5. DSM-I listed homosexuality as a sociopathic personality disorder; by DSM-III that diagnosis had been dropped. And “neurosis” was dropped amid great controversy, ruining one of my favorite jokes: neurotics build castles in the air, psychotics live in them, and psychiatrists collect the rent. DSM-IV added a new criterion: clinical significance. The current edition, DSM-5, dropped Asperger’s syndrome and subsumed it under autistic spectrum disorders. In DSM-IV, diagnoses had to employ a multi-axial template:

- Axis I: All psychological diagnostic categories except mental retardation and personality disorder

- Axis II: Personality disorders and mental retardation

- Axis III: General medical condition; acute medical conditions and physical disorders

- Axis IV: Psychosocial and environmental factors

- Axis V: Global assessment of functioning

For example, a patient who was abusing alcohol might have been diagnosed thusly:

- Axis I: 296.23 Major depressive disorder, single episode, severe, without psychotic features, 305.00 Alcohol abuse

- Axis II: 301.6 Dependent personality disorder, frequent use of denial

- Axis III: No concurrent medical conditions

- Axis IV: Threat of job loss

- Axis V: GAF = 35

The Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) had a scale of 0 to 100. Some sample scores:

- 91-100: Superior functioning, no symptoms

- 81-90: Absent or minimal symptoms (e.g., mild anxiety before an exam) …

- 51-60: Moderate symptoms or moderate difficulty in social or occupational functioning …

- 11-20: Some danger of hurting self or others

- 1-10: Persistent danger to self or others

Today, the same patient would be diagnosed under DSM-5 as:

- 296.32: Major depressive disorder

- 305.00: Alcohol use (not abuse) disorder, mild

- V62.9: Unspecified problem related to social environment

The multiaxial system was dropped in DSM-5 with little explanation. Is DSM-5 better or worse? I don’t know, but at least it’s less cumbersome. I would find it impossible to judge where anyone rated on a scale of 1-100 for anything. It’s hard enough to rate pain on a score of 1-10.

Some Concerns

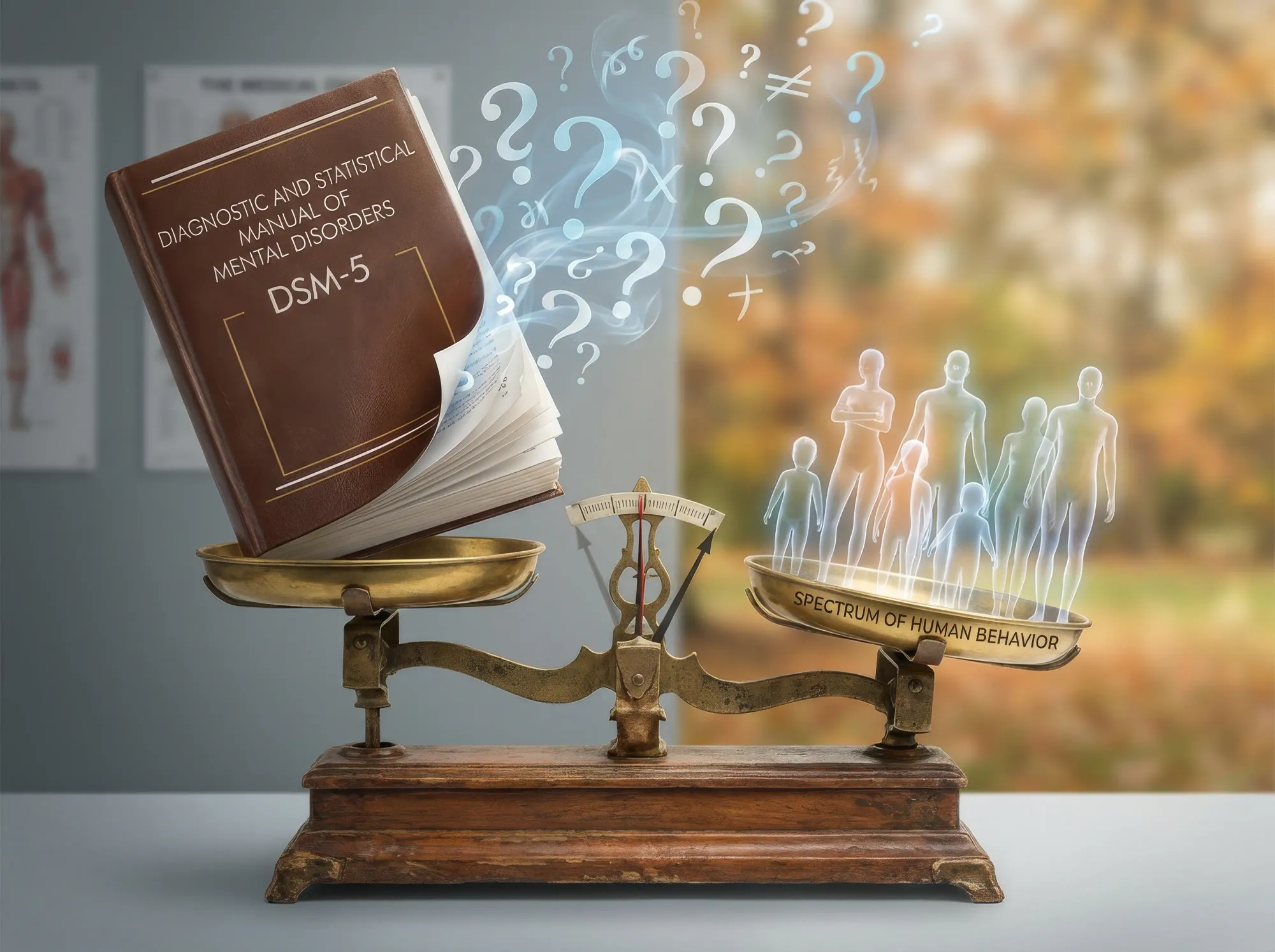

The DSM is flawed. Clinicians still frequently disagree on a diagnosis. It addresses signs and symptoms, not causes. There is an arbitrary cut-off between normal and abnormal. It disregards social context. It is culturally biased. There are conflicts of interest among those who write the manual. It tends to medicalize what may just be everyday problems of living. It puts individuals in arbitrary diagnostic pigeonholes, whereas humans fall on a continuum, with a spectrum from more to less normal. Marcia Angell, former editor of The New England Journal of Medicine, suggested, “It looks as though it will be harder and harder to be normal.”

Psychiatry no longer consigns the mentally ill to inhumane warehousing in asylums. Effective medications for psychosis, anxiety, and depression have allowed sufferers to re-join society and live meaningful lives. But there has been a backlash against the whole field of psychiatry. In The Myth of Mental Illness, Dr. Thomas Szasz claimed that there’s no such thing as mental illness, only labels that are imposed by society to control non-conformists. Scientology hates psychiatrists, blaming them for conspiring with the evil lord Xenu 75 million years ago. L. Ron Hubbard held psychiatrists responsible for the Holocaust and his followers held them responsible for 9/11. There is even a Scientology exhibit in Los Angeles named “Psychiatry: An Industry of Death.”

Antidepressants have gotten a bad rap. Tom Cruise fulminated against Brooke Shields on the Todayshow for taking drugs for her postpartum depression. The media tell us that anti-depressants are no more effective than placebos, and that they are responsible for suicides and violence. Books are published attacking psychiatry, such as Kirsch’s Exploding the Antidepressant Myth and Carlat’s Unhinged: The Trouble with Psychiatry.

Let me try to set the record straight. Yes, antidepressants are over-prescribed, and no, they don’t work much better than placebo for mild depressions. But in severe depression, they are clearly effective and save lives by preventing suicides. Psychotherapy is an option, but many patients are unable to benefit from psychotherapy until their depression is lifted enough by medications to enable them to respond and cooperate with their therapist. Some people believe patients can relieve depression by exercising. They don’t understand that severely depressed people can’t exercise; they can’t even get out of bed. Psychotropic drugs are far from ideal. They don’t work well for everyone, and they can sometimes cause devastating side effects. But they do save lives, and they do allow some patients to lead a more-or-less normal life. They are the best we have at the moment.

Conclusion

The DSM is a noble but flawed effort to standardize psychiatric diagnosis and make it more rational. I’m afraid we are stuck with it. It won’t go away, but we can hope to make it better and more scientific. Despite its flaws, it’s far better than going back to the anarchy of pre-DSM days. Its questionable diagnoses at least serve as placeholders until we can learn more. “Fever” was once a single catch-all diagnosis. We can hope that science will do for mental disorders what it has done for “fever.”