The Loch Ness Monster has hit the mainstream news media once again in a video shot by Gordon T. Holmes. Daniel Loxton takes a skeptical look at the video and provides his commentary. Daniel is the editor and illustrator of Junior Skeptic magazine and Skeptic magazine’s resident expert on cryptozoology.

New Video from Loch Ness

commentary by Daniel Loxton

Illustration by Daniel Loxton, from the Baloney Detection Series books (in production).

It’s strange what turns out to be newsworthy. As a rule, mainstream news media are all too happy to ignore such traditional skeptics topics as lake monsters; indeed, it is increasingly the case that the dedicated skeptics press has little interest in monsters and things that go bump in the night.

Yet, every once in a while, a cryptozoology story hits the mainstream press with a surprisingly big splash. This is certainly the case with new footage shot by one Gordon Holmes at Loch Ness, which is purported to show Nessie in action. This video of something-or-other on the water has garnered coverage from virtually all the major news providers of the English-speaking world (including CNN, CBS, FOX, BBC, ABC, NBC, MSNBC — even Forbes).

And yet, it’s a terrible video. In my considered opinion, it could easily be anything. Accordingly, a bewildering variety of explanations have been offered, from hoaxes (a large or mid-sized object towed by diving sled or cable; a small plastic motorized toy) to misinterpretations (birds, otters, beavers) to undiscovered species of several types (plesiosaurs, giant eels, extinct whales). This very abundance of conflicting hypotheses probably tells us all we need to know about the film: it is a kind of Rorschach test, reflecting the expectations of the viewer. As such, it is utterly useless as evidence for Nessie.

Yet, there is still more reason to keep the film at arm’s length. Commendably, cryptozoologist Loren Coleman took the time to do the obvious, running a preliminary background check on the film’s author, Gordon Holmes. As reported in Coleman’s blog, readily available web sources reveal Holmes as a man of multiple paranormal proclivities. Identified in mainstream headlines as an “amateur scientist,” Holmes is in fact a self-publisher of numerous fringe booklets linking megalithic art to cosmic forces. More to the point, Holmes claims to have had previous cryptozoological encounters, such as seeing a black panther stalking sheep in England. (This is an example of what cryptozoologists call an “ABC”, or Alien Big Cat, which is a large wild feline spotted far outside its known range).

Most damaging, Holmes claims that he has filmed fairies (“and strange Lady Figures”) at several locations — and he offers that fairy footage for sale.

Reason for caution? You bet. While it’s true that any genuine cryptid film might well come from “believers” (who have the motivation to attempt to capture such footage), the fact that Holmes has both a vested financial interest and personal dedication to the paranormal is definitely a red flag. As Coleman rather delicately put it, “Realistically, we must now admit, at the very least, Gordon T. Holmes is a bit eccentric, perhaps a shade too gullible, and if he still believes in the Cottingley Fairies photographs, which were promoted by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, then he is not current on his reading.”

Which brings us back to the media furor: if the film is so bad, and its authorship so suspicious, why on Earth has it garnered global news attention? Frankly, that’s a good question. Part of the answer must be the star quality of Nessie herself. Viewers (and therefore advertisers, and therefore networks) care about the Loch Ness monster, so it is not surprising that new footage should draw some attention. Yet, this cannot be the whole explanation. Monster films are common — many of them vastly superior in quality to this one — yet few attract a fraction of this coverage.

Like other breakout cryptozoological hits (such as the Patterson / Gimlin film), this video combines two qualities that make it compelling: it is both life-like and indistinct. Whatever it is, it gives us a powerful impression of something alive. At the same time, the weakness of the video means our imaginations are free to impose any interpretation we prefer.

In the end, this newest film tells us nothing at all about Nessie. But it does carry a message for skeptics: like it or not, skepticism’s traditional paranormal topics are alive and well — and swimming in Loch Ness.

Useful links

Benjamin Radford (photo courtesy of University Press of Kentucky).

Interview with Benjamin Radford

With a whopping new prize of £1 million offered for proof of the elusive monster, over 30 Nessie sightings were reported last week by concert goers at the Rock Ness festival (who were offered “Nessie Snapper” cameras to keep an eye on the water).

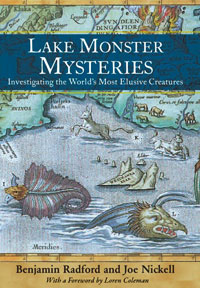

On this week’s Skepticality, Derek & Swoopy talk to Skeptical Inquirer Managing Editor Benjamin Radford about Nessie, and about his latest book (with coauthor Joe Nickell), Lake Monster Mysteries: Investigating the World’s Most Elusive Creatures .

In this week’s eSkeptic feature article, Daniel Loxton reviews Lake Monster Mysteries: Investigating the World’s Most Elusive Creatures, by Benjamin Radford and Joe Nickell (University Press of Kentucky, 2006, ISBN 9780813123943).

Lake Monster Mysteries (detail of cover)

There Be Monsters

book review by Daniel Loxton

Opening Ben Radford and Joe Nickell’s newest book, Lake Monster Mysteries, I was already pretty sure I’d like it. I admire other work by these authors, and I adore the notion of antediluvian leviathans sliding undetected through the world’s lakes, ponds, and swimming holes. (My role at Skeptic is similar to Radford’s role at the Skeptical Inquirer: go-to cryptozoology guy.)

A tremendous number of lakes are reputedly haunted by a wild proliferation of monsters. “According to surveys and research I and other cryptozoologists have conducted,” notes Loren Coleman in his Foreword to this book, “more than a thousand lakes around the world harbor large, unknown animals unrecognized by conventional zoology.”

Lake Monster Mysteries is a solid survey of this topic, and every bit as good as I expected. All your superstar favorites are here, from Nessie to Ogopogo, plus a satisfying sample of lesser-known creatures such as Memphré, Cressie, and the Silver Lake monster. Each receives its own snappy little one-chapter treatment, written in an engagingly warm and straightforward style.

The emphasis is on North American monsters. Chapter two, for example, is devoted to “Champ,” a cryptid said to inhabit the waters of Lake Champlain (a 125-mile-long lake straddling New York State, Vermont, and Quebec). Lake Monster Mysteries immediately reveals its edge over the usual recounting of cryptozoological legends — fieldwork. Nickell and Radford carry us briskly along as their visit Lake Champlain in person, interview Champ witnesses themselves, meet with cryptozoologists, and conduct a rough sonar survey of the lake with a local fishing guide.

Most uniquely, the authors conduct experimental recreations of the famous “Mansi photograph” (which depicts a convincing monster with its neck arching out of the water and looking away from the camera). Radford bravely wades into the lake holding a three-foot scale marker at 50, 100, and then 150 feet increments from shore, while Nickell photographs him (using the same type of camera used for the original Mansi photograph). Then, in a second recreation testing the witness’ estimates of monster size and distance from shore, a model Champ neck extending six feet above the water is photographed at a distance of 150 feet. Together, these experiments sweep aside previous armchair theorizing about the size of the Mansi “creature,” revealing that the “neck” extends only three feet above the water.

Radford and Nickell also review the history of Champ sightings, showing that descriptions are all over the map, as we’d expect from witnesses interpreting a wide range of ordinary phenomena in terms of the Champ legend. Sources for mistaken sightings include the lake’s endangered sturgeon (which are commonly five or six feet long “but can grow to twice that size”), otters, boat wakes, and logs.

The other chapters proceed in much the same fashion, combining literature review, personal experiences on-site, and experimental results. For a casual monster fan, it’s a one-stop shop. For a died-in-the-wool crypto enthusiast, it is as concise and informative a review treatment as you’ll find, spiced with original research that makes it a must-have volume.

Of special interest to skeptics are chapters about two hoaxed lake monsters. In the 1855 Silver Lake monster case, a sighting by several witnesses triggered a regional monster craze. Just five years later, a claim appeared in a newspaper that a fake monster had been discovered in a local hotel during a fire. It was all a hoax to drum up business. (I’m reminded here of both Loch Ness and Scooby Doo.) However, this “hoax” claim itself may be bogus. Could this be a rare example of the sort of meta-hoax crypto fans so often allege? In another intriguing hoax case, that of a monster first sighted at New York’s Lake George in 1904, the hoax is a fact of history. (Photos of the original prop monster are included in the book.) Interestingly, both of these hoax stories predate the Loch Ness Monster by decades at least.

If the book has a flaw, it might be an excessive bounty of otters. In every chapter, otters are held up as an explanation for sightings — time and again, otters, otters, otters. If a witness says she saw a multi-humped serpent in the water, Lake Monster Mysteries is quick to suggest that she may have seen a group of otters following each other. I’m prepared to bet that to some readers this explanation will sound like that UFO cliché, “It must have been swamp gas.”

There’s more to it than that, however. In fact, otters are a good explanation for many lake monster reports. Indeed, many monster descriptions positively scream “otter” (or beaver, or muskrat). For example, the authors quote one 1976 sighting of “a seal with a long neck … it was black and well above the water” of Lake Memphremagog. Sounds like an otter to me.

Likewise, many monster photos and videos have proven to record one or another of these small semi-aquatic mammals. The authors note that one especially weak film of Ogopogo “was obviously a beaver swimming with its head raised — the tail slapping the water was a telltale sign.” Indeed, “many locals were embarrassed when the film was broadcast because it made them look like they didn’t know a beaver when they saw one.”

So, yes, otters are a highly probable explanation for many specific lake monster sightings, and a fine general hypothesis for many additional “unsolved” sightings. Readers may be forgiven for finding the book’s otter hypothesis repetitive, but this is inevitable: wherever people look at water, the same illusions, mistakes, and outright boners are liable to occur. Of these, misidentification of known animals is especially common.

There are vanishingly few true, critical investigators of the paranormal, in or out of the skeptical movement. “Although library and archival research is important (and we’ve both spent plenty of time in the book stacks),” write Nickell and Radford, “it is also important, when possible, to go to the lake, interview eyewitnesses, and conduct original fieldwork.” Throughout their careers, whether dealing with haunted houses, lake monsters, or ancient artifacts, Nickell and Radford have always stood out for their commitment to hands-on, solution-oriented, practical on-site investigation.

Lake Monster Mysteries is a fine book, but its authors are a treasure. When I think of everything we skeptics still have to do, I can only wish we had a hundred like them.