In this week’s eSkeptic:

Last week’s Mystery Photo is a statue of Giordano Bruno in the Campo Dei Fiori in Rome. Bruno was burned at the stake on February 17, 1600 by the Catholic Church for heresy: for suggesting that there might be other planets and other life forms, that the stars in the sky were like the sun but further away, that the universe might be infinite, and that Copernicus might have been right in putting the sun at the center of the solar system. And, oh, he was a deist who was skeptical of Mary’s virginity and he believed that Jesus was a clever magician and not the son of God. The latter, more than his cosmology, might have done him in with the Church.

We will reveal the answer to this week’s Mystery Photo in next week’s eSkeptic.

About this week’s feature article

In this week’s eSkeptic, Richard Morrock discusses psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich’s development of pseudoscientific psychotherapy, sensational claims and extreme theories. This article appeared in Skeptic magazine, volume 2, number 3 (1994). This is a follow-up article to Epigones of Orgonomy, which appeared two weeks ago in eSkeptic.

Richard Morrock is a writer based in New York. He has been active with the skeptics movement, and has lectured on a variety of subjects to skeptical groups in New York and Philadelphia. He is also involved with the International Psychohistorical Association, of which he has served as vice president and newsletter editor. He has written a book called The Psychology of Genocide and Violent Oppression: A Study of Mass Cruelty from Nazi Germany to Rwanda

Pseudo-Psychotherapy:

UFOs, Cloudbusters, Conspiracies, and Paranoia in Wilhelm Reich’s Pyschotherapy

by Richard Morrock

The ideas of maverick psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich tend to be found on the furthest shores of American intellectual life, where conspiracy theories abound, UFOs haunt the skies, and the radical left begins to overlap with the ultra-right. Overshadowed even in the 1960s by his rival, Herbert Marcuse, Reich remained a hero and martyr to a small but fragmented group of followers, and a major influence on the thinking of a much larger group of political and sexual non-conformists who might not describe themselves as Reichians.

Wilhelm Reich was born and raised in the remote eastern hinterlands of the Austrian Empire around the turn of the century. After relocating to Vienna following World War I, he became involved with the burgeoning psychoanalytic movement of Sigmund Freud, and soon came to be regarded as its most productive disciple. At the same time, Reich was involved in Marxist politics; he was a member of the Austrian Communist Party, and was later briefly a member of the German Communist Party.

“If sexual repression is essential for the survival of oppressive class society, and if the oppressive class society imposes sexual repression, then where does one begin to eliminate oppression?”

Reich was hardly alone in combining a psychoanalytic profession with a proletarian revolutionary avocation, although he had a peculiar penchant for quarreling with others, such as Marcuse and Otto Fenichel, who shared these two orientations. Reich, however, combined the political and the personal in a way which distinguished him from even his most radical psychoanalytic colleagues. He argued that sexual repression was the basis of class oppression, and that only the liberation of the individual from his Oedipal complex could prepare the way for the emergence of social justice after the coming revolution.

This theory laid down a challenge to both the communist and psycho-analytic establishments. From the former, Reich demanded a commitment to sexual revolution which, following a short period of experimentation in the wake of the Bolshevik revolution, the followers of Lenin were unwilling to make. From the latter, Reich demanded support for both sexual and social revolution; but no psychoanalysts were prepared to call for the elimination of all sexual repression, and most were far too comfortable in their professional lifestyles to mount the barricades on behalf of the international working class. Consequently, by 1935, Reich had been expelled from the ranks of both the communist movement and the International Psychoanalytic Association.

Although his followers are oblivious to it, there is a contradiction in Reich’s prescription for society. If, as Reich argues, sexual repression is essential for the survival of oppressive class society, and if, as he also argues, the oppressive class society imposes sexual repression, then where does one begin to eliminate oppression? It cannot be done through psychotherapy, because the ruling class would not permit it; nor can it be done through revolution, because sexually repressed workers would not be able to create a truly free society — one need only look at Russia. Given Reich’s assumptions, meaningful social progress is all but impossible. It should not be surprising, then, that his most vocal group of adherents, the American College of Orgonomy, has now turned away from the original left-wing ideas of its founder, and endorses a hard-line variety of ultra-conservatism. Reich himself, late in his life, idolized Eisenhower and supported the Korean War, but even he would have hesitated to call for more authoritarianism in the public schools, or hint that the downfall of communism in Eastern Europe was really a communist plot.

The rise of Nazism in Germany and Austria compelled Reich to emigrate to the United States, following a short stay in Scandinavia, where, even in relatively liberal Norway, his radical sexual views got him into trouble with the authorities. Arriving in New York City, Reich established himself in middle-class Forest Hills and founded a school of psychoanalytic thought which he later broadened to include opinions on everything from sex education to the origins of the universe. Following his death, his adherents split into rival factions. There are now three “orthodox” Reichian organizations which fight one another tooth and nail, while at the same time heaping scorn on the “neo-Reichians” such as Alexander Lowen, founder of bioenergetics.

To his credit, Reich was the first theorist to bring the human body into psychotherapy, continuing a process which was begun, somewhat hesitantly, by Freud. Reich argued that repressed emotions were buried in what he described as the muscular armor. Sometimes he would illustrate what he termed the “segments” of the body — head, chest, pelvis, etc. — in charts which looked remarkably like those used by Hindu doctors to portray the chakras, or energy centers. Essential to Reichian therapy is the release of buried emotions through physical manipulation of the patient’s body, which is coupled with psychotherapy of a more-or-less Freudian orientation. Sometimes this had dramatic results, but they were not always positive. In cases where the patient is not prepared to accept the feelings that are released, the effects are similar to a “bad trip” on LSD. After his experience, the patient starts to believe in some pretty strange things.

Paradoxically, bad results in Reichian therapy lend support to his theories, much as alchemists’ turning gold into lead, however unprofitable, would at least prove that they were indeed able to transmute metals.

Anna Freud, who knew Reich well during his Vienna days, considered him psychotic. One can take this judgement with a grain of salt, needless to say, remembering that Reich’s advocacy of sexual liberation might not have sat too well with the celibate Ms. Freud. But by the last years of his life, Reich was showing signs of paranoia which even his most devoted followers were hard pressed to deny. Two of his later books, Listen, Little Man and The Murder of Christ, read like bizarre sermons, as Reich expounds on the perversity of narrow-minded fools who fail to recognize him as the secular messiah. These two works make Reich sound like the quintessential mad scientist.

But neither book compares with his last, Contact With Space. While Reichians accuse the United States government of totalitarian tactics because the Food and Drug Administration, in an excess of bureaucratic zeal, burned Reich’s books when they closed down his laboratory, the Reichians themselves have kept Contact With Space out of print, to ensure that the public remains unfamiliar with Reich’s curious notions about hostile flying saucers.

Unlike groups familiar to skeptics, such as MUFON and CUFOS, Reich did not merely maintain that the earth was being visited by space aliens. He went so far as to claim that the UFOs were hostile, piloted by beings he termed “CORE people” who were coming to steal our planet’s orgone energy. He even wondered if his own father was one of these “CORE people,” which would make Reich the product of interplanetary miscegenation. From the hesitant way in which he expressed this opinion, it seems that his psychoanalytic training was alerting him to the possibility that this notion was delusionary.

His followers have not always had such doubts. A graduate of Reichian therapy, Jerome Eden (now deceased), founded a group called the Professional Planetary Citizens Council, whose pretentious title disguised the fact that it never had more than eight or ten members. Eden not only pushed the theory that the earth was under attack by hostile flying saucers, he even claimed to have translated a “Cosmic Combat” manual, purportedly found at a UFO landing site along with a convenient bilingual dictionary, giving the aliens’ plans for subjugating earth through stealth and deception. “Should anyone detect our intent,” the supposed space creatures slyly declare, “the best defense is to publicly brand such outcry as preposterous and to brand such a person as obviously insane.” The author of the document quotes the great Prussian military theorist Clausewitz, raising some suspicions in my mind that he/she/it may have been from our own planet; though I suppose one should hesitate to jump to such conclusions!

Reichians have reported engaging UFOs in battle, using their “cloudbusters” — weather control devices of unproven value. In February, 1955, a group of Reichian scientists claimed to have fought off invading UFOs outside Tucson, Arizona, suffering one casualty as a heroic defender was injured by a blast of radiation. The invaders never returned. Reich himself once claimed to have driven off a UFO with his own cloudbuster near his laboratory in Rangeley, Maine.

Reichians have not been emphasizing the UFO threat in recent years. However, Peter Robins of New York City has spoken at gatherings of the American College of Orgonomy about space visitors, and seems to aspire to Eden’s title as leading Reichian authority on UFOs.

One controversial issue on which Reichians have a great deal to say is weather control. Reichians, with their “cloudbusters” based on “orgone energy,” claim credit each time a drought ends in the West, although rival Reichian groups often fight with each other over whose experiments actually caused it to rain. The unproven claim of weather control tends to alienate some people who might otherwise be attracted to Reichian ideas; saving the world is one thing, playing god is another. Reichian die-hards, nonetheless, expect that their rain-making experiments will compel doubters to accept their entire cosmology.

“Reichians with their ‘cloudbusters’ claim credit each time a drought ends in the West, although rival Reichian groups often fight with each other over whose experiments actually caused it to rain.”

Another theory adhered to by Reichians is spontaneous generation. Reich argued that living forms could arise from inorganic matter in sealed, sterilized test tubes containing ordinary backyard debris boiled in water. If this were true, it would invalidate all biological research over the past few centuries. Reich was contemptuous of critics who argued that the appearance of amoebas and other micro-organisms in his test tubes were due to his inadequate controls, which allowed spores to survive in the medium. His followers argue that conventional scientists are unable to appreciate Reich’s discoveries because they are “armored” by their neuroses — sort of a modern-day equivalent of the Emperor’s New Clothes. They say that if other scientists underwent orgonomic therapy, they would see the same phenomena which the Reichians report from their own labs. This might well be true, if one were to assume that Reichian therapy is so harmful that it consistently causes people to see things that are not there.

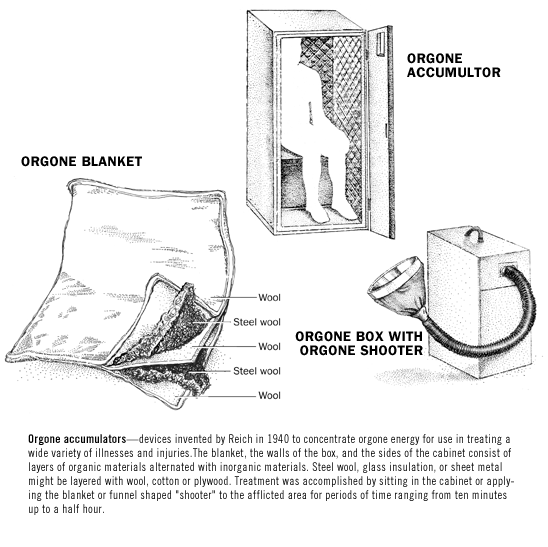

Reich ended his life in prison, dying of a heart attack just before he was scheduled to be released. The original charge against him was selling “orgone accumulators” across state lines, which got him into trouble with the FDA. However, he could have easily beaten this charge if he had wanted to. Reich refused to contest the charge in court on the basis that his “scientific” doctrines could not be argued in a court of law. He was convicted not of fraud or quackery, but of contempt of court.

Reich’s followers hold that their leader was framed as part of a communist plot and that the U.S. government, at the height of the Cold War and after years of McCarthyite hysteria, was acting as Moscow’s instrument when it prosecuted Reich.

Ironically, Reich’s original aim was to purge Freud’s doctrine of its metaphysical baggage and put it on a sound scientific basis. But as his school of thought developed, it began to include more and more long-discarded theories and folk tales, dressed up in pseudoscientific terminology and confirmed by dubious experiments which non-Reichians have not been able to replicate. Spontaneous generation is revived in Reich’s descriptions of “T-bacilli.” Animal magnetism becomes orgone energy and the Yin and Yang of Mahayana Buddhism are reworked into Reich’s theory of cosmic superimposition.

What Reich never broke with in psychoanalysis was the notion of reductionism, which sees social events as nothing more than the reflection of psychological reality. Reich, in fact, carried this even further by attempting to reduce psychology to biology and physics, the latter being, as Martin Gardner pointed out, a subject about which Reich had far too little knowledge. Coupled with his own authoritarianism and his apparent inability to distinguish objective from subjective phenomena, Reich’s reductionism led him to develop a pseudoscientific psychotherapy which exceeds all others both in its scope and in the dogmatism and intolerance of its adherents. ![]()

Skeptical perspectives on pseudoscience; plus latest additions…

-

The New Age: Notes of a Fringe Watcher

The New Age: Notes of a Fringe Watcher

$26 by Martin Gardner

-

Browse the latest additions to Shop Skeptic

Browse the latest additions to Shop Skeptic

books and lectures by various authors

NEW ON SKEPTICBLOG.ORG

The Top Ten Science Books of 2010

In the tradition of making end-of-the-year lists of the “Top 10 X” Michael Shermer presents his personal picks for the Top 10 Science Books of 2010. Most of these books are available in audio format as well as the old-school ink-on-bound-paper format, and Shermer highly recommends Audible.com as the go-to source for easy listening to these selections while driving or riding your bike from your MP3 player or iPhone/iPod (use one ear bud instead of two so you can hear on-coming traffic, ambulances, etc.)…