In this week’s eSkeptic:

- for students: The Tyson Jacobsen Science Symposium Scholarship

- reminder: group discount ends April 30 for our Alaskan Geology Cruise (August 7–14, 2011)

- feature article: Zeno’s Paradox and the Problem of Free Will

- price reduction: on two of Michael Shermer’s college audio courses

- our next lecture: A Natural History of the Planet (by Dr. Tim Fannery)

- Mystery Photo: previous photo revealed, plus a new photo

The Skeptics Society is pleased to announce that one of our patrons, Tyson Jacobson, has generously offered to cover the $99 entry fee for 100 students to attend the Science Symposium at Caltech on Saturday, June 25, all day and evening, featuring Dr. Michael Shermer, James “The Amazing” Randi, Bill Nye the Science Guy, and Mr. Deity (Brian Dalton). Breakfast, lunch and dinner on Saturday are included; travel and lodging are not included.

Open to full-time college or high school students

Full-time college or high school students can apply for this scholarship. Please email, fax, or mail a copy of your current student ID and the phone number of school registrar who can verify your student status along with your completed application. (Our contact details are on the application form, which can be submitted via email once it is complete using the free Adobe Acrobat.) Please feel free to share this scholarship invitation with other students who might be interested in attending.

For high school students, the scholarship fund will also cover the entry fee for one chaperone per group of ten high school students.

About this week’s feature article

In this rich article on an ancient problem, Skeptic contributor Phil Mole discusses the problem of free will. The problem is this: how can we hold people accountable for their actions if we live in a determined universe? A variety of solutions to the problems are reviewed from the ancient Greeks to modern scientists, philosophers, and even science fiction writers such as Philip K. Dick in his classic novel Minority Report. Mole finds compelling new arguments from complexity theory and cognitive neuroscience that reveal the intricate network of causes and effects at work in our conscious minds. This article appeared in Skeptic magazine volume 10 number 4 (2004).

SUBSCRIBE to Skeptic magazine for more great articles like this one.

Zeno’s Paradox

and the Problem of Free Will

by Phil Molé

John Anderton, the protagonist played by Tom Cruise in Steven Spielberg’s science fiction film Minority Report, finds himself in a nightmarishly paradoxical situation. As a policeman for the futuristic Pre-Crime office, Anderton relies on an elaborate information arrangement system to see crimes before they happen, and arrest the would-be perpetrators.1 The accuracy of Pre-Crime’s predictions seems infallible, until it forecasts that Anderton himself will soon become a murderer. Anderton does not even recognize the future murder victim, so how could he possibly kill the man? How can he prove his innocence, especially since the system seems to have perfect predictive accuracy? Is it possible that the system is right, and Anderton will become a murderer for reasons beyond his own knowledge or understanding? If Anderton is to avoid his apparent destiny as a convicted murderer, he must hope that the astonishing predictive accuracy of Pre-Crime leaves some room for personal freedom. He must hope that deterministic laws do not preclude the possibility of free will.

Minority Report, based on a Philip K. Dick story, grapples with the classic philosophical problems of free will. Do human beings have free will, or do physical laws determine our destinies? How can the novelty of free choice truly exist in a universe organized with such clock-like regularity? These questions have intrigued and annoyed contemplative folks for millennia, and have provided the raw material for weighty philosophical treatises and science fiction movies alike. Yet, after centuries of debate, the definitive answers to the free will dilemma have yet to be discovered. Is this problem, as some philosophers have maintained, ultimately beyond human understanding?

Perhaps we need to take a new, closer look at the problem and its history. We may be able to identify conceptual flaws in the logic of many free-will arguments. More important, we may be able to find fruitful parallels between the apparent puzzles at the center of the free will debate and other difficult philosophical puzzles, such as the motion paradoxes of Zeno. Such an inquiry may yield insights relevant to the historical problem of free will and its possible solution.

The Problem: A Brief History

To the ancient Greeks, human destiny was subject to forces beyond our control, and tragedy resulted from the heroic but useless struggle against the dictates of destiny. After the beginning of the Christian era, theologians developed new concerns. They worshipped an all-powerful and all knowing God, but soon found that the existence of this God would have rather negative implications for human freedom. If God really knew everything, he would have to know the course of all history. But if this were true, we humans seemed to be simply going through the motions like characters in a novel. We are like the protagonists of Tom Stoppard’s brilliant play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, who do not fully comprehend their status as minor Hamlet characters lacking true personal freedom.2 Just as the audience attending a performance of a widely read play knows the fates of every character, God knows the future details of every human being alive, because he himself authored our destinies.

A deterministic universe also seemed to pose serious threats to morality and accountability. If we do not freely choose our actions, how can we be responsible for good or evil deeds we happen to perform? What sense could it even make to punish a criminal for breaking the law if he could not have done otherwise? Even theological doctrines, such as the rebellion of Satan and the crucifixion of Jesus, seem to become uncomfortably troublesome upon further reflection. For if Satan’s fall and Christ’s acceptance of the cross were ordained to happen exactly as they did, how could we justifiably despise the Prince of Lies or love Jesus? Sin could not truly exist, since the existence of sin depends on the existence of choice. Adam and Eve might have eaten of the fruit of the tree of knowledge, but they could not have violated God’s will if God is omnipotent. The fall of man seems, in this light, to have been something thrust upon us by necessity, not by choice. Even worse, it becomes difficult to morally justify God’s actions in history, since He must know that some of his actions will place his most beloved creation in horrible pain and misery.3

Theologians eventually devised various compromise solutions to the free will dilemma. Religious thinkers modified their definitions of omnipotence to include the possibility that human actions could be free and simultaneously known in advance by a supreme being. Foremost among these theologians was Thomas Aquinas, who worried that too much disparagement of free will might lead people to doubt the reality of sin, and abdicate responsibility for their actions.4 These new thinkers stressed that God’s vast knowledge of reality did not imply that human actions were not free. Just as an observer in a 15th story apartment window can see that two automobiles are unwittingly driving on a collision course, God’s vantage point allows him to see the consequences of our actions, even when they are hidden from our own senses. We choose our actions based on our best available information, but simply do not know enough to accurately foresee the outcomes of our actions. Adam and Eve were responsible for their choice after all.5

Yet another, more philosophical objection to free will states that its existence is entirely dependent on the possibility of “uncaused causes.” That is, if we are honestly to consider ourselves free, then we ourselves must be the only cause of our actions. We must be able to demonstrate that we do not act the way we do because prior events compelled us. But this is not reasonable, say the objectors, because every action in the material world can be traced to prior causes, and these causes themselves originate from prior causes. All causes are part of a chain of events stretching back to the very beginning of the universe.

All right, but we are people, not material objects. An inanimate clump of minerals cannot choose what it is going to do, but we can, because of our human consciousness. The materialist is not satisfied with this rebuttal. He will state that human beings are made of matter that follows the same physical laws governing everything else in the universe. We are made of atoms, and the behavior of these atoms follows known laws and results from physical causes. When we trace the histories of all the bits of matter comprising our physical bodies, we see that the movement of this matter followed inexorably from a long series of perfectly material determinants. The thing we call our mind is merely the sum of myriad interactions of material particles following immutable natural laws. With a sufficiently intimate understanding of our minds at the material level, we could no longer imagine we are acting freely.

To determinists, our perception of personal freedom is a side effect of consciousness that, ironically, developed from a combination of natural laws and prior constraints in the pathway of human evolution. This consciousness gives each of us a sense of personal identity that allows us to perceive that we are somehow separate and independent from the rest of the world. We seem to be free agents, exempt from external constraints. But as Leo Tolstoy observed in War and Peace, we cannot easily consider ourselves free when we recall prior sequences of events that limited our choices and compelled us toward certain courses of action.6 The military generals in Tolstoy’s epic imagine they are controlling the fates of entire armies and even nations, but countless historical contingencies they are unable or unwilling to consider rigidly determine their every action. What it all comes down to, as philosophers from Friedrich Nietzsche to Galen Strawson have argued, is that we cannot be a causa sui, or the ultimate cause of ourselves. We had no say in the forces that produced us, and so we cannot be free in any ultimate sense of the word.7

Free will is simply an illusion conjured by our ignorance of the causes affecting our behavior. This is what Baruch Spinoza meant when he quipped that if a rock possessed consciousness, it would believe that it fell of its own free will.8 The deeper we look at the various determinants bearing upon our actions, the more free will seems to be an abstraction without meaning in the real world. This seems to be true even if, as philosopher P. F. Strawson argued in a celebrated paper, belief in free will is a deeply ingrained component of human ethical reflection — we believe in free will because denying freedom undercuts the health of our social relationships.9 Someone who could know the myriad effects impacting our behavior would see that our every action is completely determined and predictable. As the mathematician Laplace famously argued,

An intellect which at any given moment knew all the forces that animate nature and the mutual positions of the beings that comprise it, if this intellect were vast enough to submit its data to analysis, could condense into a single formula the movement of the greatest bodies of the universe and that of the lightest atom: for such an intellect nothing could be uncertain, and the future just like the past would be present before its eyes.10

The Search for Solutions

Undeterred, champions of free will continue to defend their theory from the clutch of determinism. One common approach is to cite the importance of non-material factors on human behavior, such as culture. We are more than mere collections of atoms or genes. We are also social creatures capable of adapting to a wide range of cultural habitats. Hasn’t anthropology taught us that human nature is remarkably malleable?

Determinists object that culture has no relevance to the question of free will. They argue, quite correctly, that all choices ultimately stem from cognitive activity in the brain, which remains a material entity subject to material laws. Furthermore, it wouldn’t even matter if culture allowed us to bypass our material structures altogether. If our behavior results from cultural factors, it is still determined by external factors, and we still do not freely choose our actions.

Modern opponents of determinism invoke quantum mechanics as proof that chance events have their place in nature. In quantum mechanics, we can only cite probabilities for finding particles in a particular place, and cannot determine the position of a particle in advance. Might quantum mechanics provide a means of escape from a determined existence? According to physicist Roger Penrose, in his popular book The Emperor’s New Mind,11 quantum mechanics enables us to escape from a completely knowable and determined existence by injecting randomness into the very nature of consciousness.

Determinists respond that not every scientist thinks that quantum mechanics is a truly nondeterministic theory. Some physicists maintain that quantum mechanics equations contain hidden variables that cause determinism to prevail, despite the seeming randomness in experimental results. And even if quantum mechanics is random, how does that help the case for free will? To most people, freedom involves more than performing random actions or responding randomly to stimuli. We want to be able to choose our actions, not simply behave haphazardly. A life completely subject to the whims of quantum chance is just as unattractive as a life governed by predictability.

Free Will and Zeno’s Paradox

The arguments for and against free will have circulated through the intellectual world for millennia, with minor variations. We may sympathize with André Gide, who once mused that all the arguments about free will have already been made, but we must continue repeating them because nobody listens.12 Indeed, although some of the terms used in the debate may vary, the basic arguments continue to center on the likelihood of uncaused causes and the possibility of autonomy from natural laws. Whether the movements of atoms or the influence of genes and cultural conditioning control us, we are not the ultimate cause of our actions, and cannot truly be free. The existence of free will seems to depend on a logically impossible reconciliation of incompatible concepts. As Martin Gardner quips, “A free will act cannot be fully predetermined. Nor can it be the outcome of pure chance. Somehow it is both. Somehow it is neither… My own view, which is Kant’s, is that there is no way to go between the thorns. The best we can do (we who are not gods) is, Kant wrote, comprehend its incomprehensibility.”13

But are we really looking at the problem correctly? Perhaps we need to escape from the cycle of rehashed arguments and take a new look at our approaches to the problem. One way to do this may be to look for analogous dilemmas encountered during the long history of philosophy, and see if we can gain insights relevant to discussions of free will.

To my mind, some important aspects of the free will debate invite comparison to another celebrated philosophical puzzle — the motion paradoxes of the Greek philosopher Zeno. Living in the fifth century BCE, Zeno was a disciple of the great thinker Parmenides, who famously argued that change in the physical world is impossible. We cannot speak of what is not, Parmenides said, since that would involve the contradiction of speaking of things that don’t exist.14 Change is therefore impossible because it involves something becoming what it is not, which plainly involves an impassable contradiction.

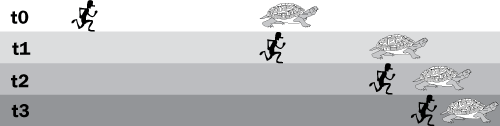

Zeno defended the rather paradoxical conclusions of his mentor by developing a number of paradoxes of his own. In one of his most famous examples, Zeno describes a race between the swift runner Achilles and a tortoise.15 Since Achilles runs much faster than the tortoise, we give the tortoise a fair head start. Everyone knows Achilles will outrun the slow, heavy tortoise, right? Don’t be so sure, Zeno answers. Suppose the tortoise has a ten-meter head start. Achilles catches up that distance, but in that time, the tortoise has moved a small distance ahead. Achilles must now catch up the new distance, but meanwhile the tortoise has made further small progress. It turns out that Achilles can never overtake his slower opponent, because each time he moves the tortoise has trudged another tiny increment ahead.

Figure 1: This illustration depicts Zeno’s famous paradox of the race between Achilles and the tortoise. Achilles cannot win the race because each time he tries to catch up, the tortoise has moved another small distance ahead. Redrawn from The Philosopher’s Magazine.16

This paradox also implies that Achilles not only fails to outrun the tortoise, but neither Achilles nor anything else can truly move at all. Before I can move from one side of the room to the opposite side, I first have to travel half the total distance. But before I can reach the center of the room, I have to travel half of that distance, or one-quarter of the total. We can still divide the quarter distance by two again, and continue this operation until we have added an infinite number of small distances to our journey. This same argument applies if, instead of wishing to cross the room, we merely want to move a tiny fraction of an inch forward. Any potential distance, no matter how great or small, is divisible into an infinite number of smaller distances. We can never move anywhere, because we would have to travel across an infinitely large number of distances just to move a vanishingly small distance.

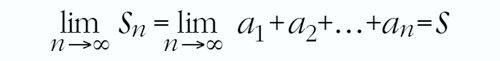

Zeno’s paradox is one of those philosophical arguments that is obviously wrong, but resists attempts to find the error. His argument baffled generations of philosophers who struggled unsuccessfully to locate the fallacies in his thinking. We needed new developments in mathematics to clearly understand where Zeno’s reasoning goes astray. The mathematical concept of series convergence allows us to see that an infinite series of small increments can comprise a finite sum. An infinite number of increments does not necessarily produce an infinite number, but may converge on a finite number.17 This can be expressed mathematically as

For instance, suppose we sum an infinite series beginning with ___, and each new term is exactly ___ of the previous term. We are adding an infinite number of terms, but do not obtain an infinite sum, because our series converges to one:

Thus, the mathematics of convergence shows that an infinite series does not necessarily imply an infinite sum. The seeming paradox in Zeno’s argument arises because of our mistaken tendency to see the concepts of “infinite” and “finite” as mutually exclusive. Zeno’s rigid rationalism convinces us that an infinite series of small increments prevents a finite increase in distance, but the narrow focus and hidden assumptions in Zeno’s argument have tricked us into believing a fallacy. We can cross the room after all, and Achilles really does outrun the tortoise.

Paradox Lost: Rethinking Free Will Arguments

I would like to hypothesize that free will arguments contain common misunderstandings of the concepts of “cause” and “will,” and these misunderstandings are analogous to Zeno’s erroneous assumptions about the concepts of “infinite” and “finite.” Just as Zeno agonized about infinite numbers of small distances and convinced himself that all movement was impossible, most participants in the free will debate devote so much attention to the causes affecting us that they feel compelled to deny free will. Indeed, many philosophers believe the case against free will to be rock solid. Every effect has a cause, and humans cannot be the causes of their own consciousness, so we may as well just admit that free will is illusory. A few of these philosophers even smugly claim that anyone can see the logical impossibility of free will by reflecting on the relevant arguments from the comfort of his own couch.18

However, Zeno also thought he used flawless logic in his demonstration of the impossibility of motion. Just as modern determinists intimidate us by speaking of infinite chains of causes precluding our freedom, Zeno intimidated his audience by showing how infinite numbers of small increments rendered motion impossible. What if, just as in Zeno’s paradox, there is nothing truly paradoxical going on in the realm of free will after all? What if our actions could remain genuine acts of will and outcomes of a complex chain of causality, just as we could have an infinite series of small increments converge on a finite sum?

These possibilities are similar in many ways to other counterintuitive conclusions rendered understandable through careful mathematical reasoning. For instance, we tend to think that the concepts of “randomness” and “symmetry” are at odds with each other. A symmetrical pattern seems to be the very antithesis of randomness. But as physicist Taner Edis shows in his remarkable book The Ghost in the Universe, order and chance are closely linked. A long series of fair coin tosses likely results in random sequences of heads and tails, but the resulting randomness follows directly from the symmetry in the probabilities of obtaining two possible outcomes for each coin flip. Similarly, we observe magnets to be rotationally symmetric at high temperatures, meaning that they align themselves in every possible direction. The overall magnetization of this system is zero, because the magnets do not favor any particular direction and cancel each other out. Ironically, if the equations describing magnetism were not symmetrical, the directions of these magnets could not be random, because non-symmetrical equations would result in a non-zero net magnetization of the system, dictating that the magnets align themselves along a single direction.19 Symmetry and randomness are not antagonists. They are inseparable elements of a universe in which mathematically elegant laws create opportunities for contingencies.

Free will certainly poses vexing philosophical problems, but many of these problems appear to result from conceptual confusions. When we talk about free will and determinism, we immediately confront a series of conflicts between seemingly contradictory terms. When we ask if a deterministic universe implies the absence of freedom, we seem to encounter a conflict between the concepts of cause and choice. We stumble upon another impasse when we ask if quantum indeterminacy somehow enables us to have free will, because we see randomness and rational choice as complete antagonists. But we’ve fooled ourselves as much by our framing of our questions as Zeno fooled himself, and many others, by the framing of his paradoxes. We do not have to choose between complete determinacy and complete chance, or believe that free choice necessitates complete isolation from the world of causes and effects.20 Instead, we can explore the ways that chance and order combine in physical laws to allow free will to exist.

The first thing we need to do is clarify what “free will” really means. It clearly cannot imply total freedom to do whatever we want, because few people worry about their inability to suddenly become lighter than air. Most people willingly accept that the nature of our human bodies imposes limits on our actions. To claim we have free will, then, is merely to claim that we have some range of possible choices. The mere presence of limits on our choice does not negate our freedom as long as real choices still exist.

To see why, consider an example provided by philosopher Daniel Dennett in his interesting book Elbow Room. If we see an animal at the zoo in a tiny cage restricting even the smallest movement, we deplore the poor beast’s condition, because he seems to lack freedom to do anything at all. But now imagine seeing the same animal in a spacious zoo habitat. The animal still faces limits on his freedom, but he can roam around in his quarters and “choose” to be in one place rather than another.21 This is the kind of freedom we would probably consider sufficient. We are mostly comfortable with the idea of limits on our choices, as long as we truly have a variety of options.

If the tradeoff between freedom and limitations is not all or nothing, neither is the tradeoff between freedom and deterministic predictability. Recall that traditional determinists argue that an omniscient being seeing all of the causes affecting us would be able to perfectly predict our actions. This hypothetical being would be able to see that we do not actually act freely, but act under the compulsion of countless causes undetected by our limited mortal senses. This is a nice argument, but it suffers from the serious deficiencies that no one knows if such a being exists, and no one certainly knows how such a being would perceive reality. It may very well be the case that a being capable of seeing all of the causes acting on us would have more difficulty predicting our behavior. After all, the simpler of two competing scientific models often allows us to make the most accurate predictions. Predictive accuracy often decreases, not increases, with the number of parameters we include in our model!22 An all-knowing being may very well wind up with all-powerful headaches.

One reason that determinism does not imply an absence of alternatives is the role of emergent phenomena in complex systems. An emergent phenomenon is neither a property of any individual component of a system, nor simply the result of summing the properties of all components. Emergent phenomena are novel, and unpredicted by our knowledge of the system.23 There are many examples of emergent phenomena at all levels. For instance, the atomic properties of hydrogen and oxygen do not convey all possible information about the properties of water, which is simply a molecule made from the combination of the two elements. Water has distinct properties, such as its surface tension and heating capacity, that belong neither to hydrogen nor oxygen and do not arise from simply combining the known properties of each. Some evolutionary biologists think that stable reproductive species in evolutionary history are emergent phenomena, which changed the whole course of natural selection.24 This illustrates another important feature of emergent phenomena — their tendency to affect other parts of the system that produced them. Genes control the inheritable traits of species, but species take the evolutionary game to a completely new level, and affect the distribution of genes themselves in complex ways. This is a feature of complex systems often overlooked by strict determinist deniers of free will. Emergent phenomenon themselves are not merely affected by their surroundings, but interact dynamically with other parts of the system.

By almost anyone’s definition, the human mind is a complex system. Consciousness is an emergent phenomenon of the billions of neuron interactions in our brains, and seems to be able to influence the behavior of these neurons in novel ways. Some of this novelty may also be linked to quantum level uncertainty in the states of the neurons involved.25 Determinist opponents of free will, hearing this, may reiterate their objection that quantum uncertainty cannot provide a foundation for the kind of rationally considered choices we associate with free will. But as we have already seen, this objection is unwarranted, because randomness and order are not incompatible concepts. As Taner Edis’ magnetic field example showed, randomness is an inherent characteristic of deterministic laws. Quantum mechanics may supply more variety for these laws to act upon, and the neurons of our brain may be close enough to the quantum size level for this variability to be considerable.

How, then, does free will work? We do not completely understand, but we have clues. And just as we needed the mathematical development of calculus to clearly resolve Zeno’s paradox, we may find that the burgeoning mathematics of complexity theory will finally help us dispel our conceptual confusions about free will. Currently, it seems probable that complexity theory, together with our growing understanding of cognitive neuroscience, will throw much light on the process of making willed decisions. We will better understand how the complex arrangement of neurons in our brains leads to emergent states of conscious awareness, and the conscious mind feeds back on its neural networks to place itself in alternate conscious states. With time, we will also better comprehend how the brain converts sensory stimuli and knowledge of our environment into neural impulses and becomes part of the intricate network of causes and effects at work in our conscious minds. Finally, we will realize the conceptual confusions that cause us to see determinism and rational choice as incompatible, and will renounce our error. We will live in a deterministic world without fear, for we will no longer see determinism as a threat to the free will we cherish.

References

- “Minority Report” screenplay. Dick, Philip K. 2002. Minority Report and Other Classic Stories. New York: Citadel Press.

- Stoppard, Tom. 1967. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead. London: Faber and Faber.

- This issue is central to the problem of theodicy, or how to reconcile the existence of evil in the world with the existence of an omnipotent, omniscient and benevolent God. One of the classic examples is Leibniz, Gottfried William, 1988, Theodicy, Chicago: Open Court. Hicks, John Mark, 1999. Yet I Will Trust Him: Understanding God in a Suffering World, College Press Publishing Company is worth reading, and Davis, Stephen T., 1995. Encountering Evil: Live Options in Theodicy, Westminster John Knox Press provides useful summaries of various theodicies used by contemporary theologians. For a brilliant and provocative literary exploration of the implications of divine omnipotence on concepts of God’s goodness, read Saramago, Jose, 1994. The Gospel According to Jesus Christ, New York: Har vest Books. In addition to its relevance to issues discussed here, Saramago’s book is also one of the most passionately imagined and beautifully written novels of recent years.

- In his Summa Theologica, Aquinas argues that “man has free-will: otherwise counsels, exhortations, commands, prohibitions, rewards, and punishments would be in vain.” See Aquinas, Thomas. 1920. The Summa Theologica of Thomas Aquinas: Second and Revised Edition. Translated by Fathers of the English Dominican Province. Online Edition prepared by Knight, Kevin. 2003. www.newadvent.org/summa/108301.htm.

- See, for example, Milton’s similar solution in Paradise Lost. Milton, John. 1993. (1674). Paradise Lost: An Authoritative Text, Backgrounds, Sources and Criticism. New York: W.W. Nor ton & Company. One of the many fascinating things about Milton’s masterpiece is the way it responds to some of the growing rational criticisms of Biblical Christianity in Milton’s time.

- Tolstoy, Leo. 1996. (1869). War and Peace: An Authoritative Text, Backgrounds, Sources and Criticism. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

- Strawson, Galen. 1986. Freedom and Belief. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Spinoza, Baruch. 1992. (1677). Ethics. Translated by Samuel Shirley and Seymour Feldman. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company.

- Strawson, P.F. 1962. “Freedom and Resentment.” Reprinted in Strawson, P.F. (ed.) 1968. Studies in the Philosophy of Thought and Action. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- La Place, Pierre-Simon. 1951. (1814). A Philosophical Essay on Probability. Translated by F.W. Truscott and F.L. Emory. New York: Dover Books.

- Penrose, Roger. 2002. The Emperor’s New Mind: Concerning Computers, Minds and the Laws of Physics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gide, Andre. 1891. Le Traite du Narcisse. In Littlejohn, David (ed.) 1971. The Andre Gide Reader. New York: Knopf.

- Gardner, Martin. 1999. (1983). The Whys of a Philosophical Scrivener. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin.

- Gottlieb, Anthony. 2000. The Dream of Reason: A History of Philosophy from the Greeks to the Renaissance. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

- Ibid. For a more technical discussion of Zeno’s paradox, see Barnes, Jonathan. 1982. The Presocratic Philosophers. London: Routledge Books.

- Illustration from The Philsopher’s Magazine website. See Moorcoft, Francis. The Philosopher’s Magazine on the Internet. Downloaded March 24, 2003 from www.philosophers.co.uk/cafe/paradox5.htm

- For a technical discussion of series convergence, see Knopp, Konrad. 1956. Infinite Sequences and Series. New York: Dover. Readers seeking more general treatments of series convergence may consult the relevant sections of Whitehead, Alfred North. 1948. (1911). An Introduction to Mathematics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, and Maor, Eli. 1987. To Infinity and Beyond: A Cultural History of the Infinite. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- For instance, Galen Strawson recently proclaimed that the impossibility of being a causa sui negates the potential for being a free moral agent “whether determinism is true or false. It’s a completely a priori argument, as philosophers like to say. That means you can see it is true just by lying on your couch. You don’t have to get up off your couch and go outside and examine the way things are in the physical world.” This interview is available in “Interview with Galen Strawson.” 2003, The Believer, Volume 1(1), 78–86.

- Edis, Taner. 2002. The Ghost in the Universe: God in the Light of Modern Science. Buffalo:Prometheus Books.

- For valuable discussions of the fallacies of “slippery slope” arguments, consult Walton, Douglas. 1994. Slippery Slope Arguments: Studies in Critical Thinking and Informal Logic Number 4. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dennett, Daniel C. 1984. Elbow Room: The Varieties of Free Will Worth Wanting. MIT Press. Dennett has recently expanded his arguments about free will in Dennett, Daniel C. 2003. Freedom Evolves. Oxford: Oxford University Press. I agree with Dennett’s conclusion that determinism is compatible with free will, and his argument that free will and consciousness are complex products of an evolutionary pathway. However, I do not share his aversion to indeterminacy as a contributor to free will, and I am quite skeptical of the value of memes for explaining human thought and actions.

- An excellent discussion of the inverse relationship often observed between the complexity of a scientific model and its predictive abilities is found in Sober, Elliot. “Instrumentalism, Parsimony and the Akaike Framework.” 2000. Proceedings of the Philosophy of Science Association. Available online at www.philosophy.wisc.edu/sober/papers.htm. This issue is also addressed in Mole, Phil. 2003. “Ockham’s Razor Cuts Both Ways: The Uses and Abuses of Simplicity in Scientific Theories.” Skeptic, 10(1).

- See Morowitz, Harold J. 2002. The Emergence of Everything: How the World Became Complex. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- For instance, Stephen Jay Gould and other evolutionary theorists often argued that selection at the species level, instead of the individual level, is a driving force of evolution. See Gould, Stephen. 1997. “Self-help for a hedgehog stuck on a mole-hill. Review of Richard Dawkins’ Climbing Mount Improbable.” Evolution, 51(3), 1020–1023.

- An interesting explanation along these lines is available in Stickgold, Robert. “Tricking Heisenberg: Free will as an emergent property of attentional and emotional subsystems.” Unpublished draft paper.

Skeptical perspectives on free will and determinism…

-

The The Science of Good & Evil

The The Science of Good & Evil

by Michael Shermer -

Offer an original model of the bio-cultural evolution of morality and a new theory of provisional ethics that challenges the reader to confront these timeless issues from a new perspective — one that suggests that both morality and immorality evolved in human biological and cultural evolution, that we can make free moral choices in a determined universe, that moral principles can have a sound rational basis supported by empirical evidence (without being dogmatically absolutist or dependent on an external source of validation), and that we can be good without God. READ more and order the book.

-

Freedom Evolves: Free Will, Determinism,

Freedom Evolves: Free Will, Determinism,

and Evolution

by Dr. Daniel C. Dennett

-

From Particles to People: The Laws of Nature

From Particles to People: The Laws of Nature

and the Meaning of Life

Dr. Sean M. Carroll -

The progress of modern science has reached a point where the laws underlying everyday life are completely understood. This understanding lets us draw strong conclusions about the milieu in which we live. There is no telekinesis, astrology, or life after death. What does this mean for our understanding of consciousness, free will, and the meaning of life? Taking the laws of nature seriously opens a vista of possibility, freeing us from outmoded ideas about what it means to be human. READ more and order the lecture.

Lecture this Sunday at Caltech

Here on Earth:

A Natural History of the Planet

with Dr. Tim Flannery

Sunday, May 1, 2011 at 2 pm

TIM FLANNERY IS ONE OF THE WORLD’S MOST INFLUENTIAL SCIENTISTS. In Here on Earth Flannery presents a captivating and dramatic narrative about the origins of life and the history of our planet. Beginning at the moment of creation with the Big Bang, Flannery explores the evolution of Earth from a galactic cloud of dust and gas to a planet with a metallic core and early signs of life within a billion years of being created. He describes the formation of the Earth’s crust and atmosphere, as well as the transformation of the planet’s oceans from toxic brews of metals to life-sustaining bodies covering 70 percent of the planet’s surface. Life first appeared in these oceans in the form of microscopic plants and bacteria, and these metals served as catalysts for the earliest biological processes known to exist. From this starting point, Flannery tells the fascinating story of the evolution of our own species. Order the book on which this lecture is based from Amazon.com.

Ticket information

Tickets are first come first served at the door. Seating is limited. $8 for Skeptics Society members and the JPL/Caltech community, $10 for nonmembers. Your admission fee is a donation that pays for our lecture expenses.

Can’t Make it to Our Lectures?

Get them on DVD!

Many of you would love to be able to make it to our lectures at Caltech, but cannot. And, many of you may not realize that we record almost all of our lectures and sell them on CD and DVD through our online store.

This week’s Mystery Photo:

What mythic creature is this and to what did she give birth in history? (Click to enlarge)

Solution to last week’s photo

The Mystery Photo from April 20th is of David Irving, at a June 2008 event in Orange County, California, where he spoke for the Institute for Historical Review, the primary organization behind so-called “Holocaust revisionism.” The posters of Hitler and his cronies were available for sale at the lecture, along with most of Irving’s books, along with many other gems, such as The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion, Henry Ford’s The International Jew, and of course the perennial favorite Mein Kampf.

Click the words in the sentences above to see more photos. We will reveal the answer to this week’s Mystery Photo in next week’s eSkeptic.