In this week’s eSkeptic:

Skepticality Has Reached its 200th Episode!

“You don’t look a day over 100! See, it shows that a diet of clear thinking and reasoned science is good for your health and longevity. Congrats on your 200th episode and on surpassing 2 million downloads! I thank you for your important work and contribution to the overall skeptical literature that is cumulatively making the world a better place to live.”

About this episode

In this, the 200th episode, Derek sits down with Swoopy for a long while to ramble about the past (and future) of the podcast (and a bit about what Swoopy’s been up to while absent from the show). Derek then talks with Dr. Michael Shermer about the recent news surrounding Lance Armstrong and the reality of doping in athletics. They also discuss Michael’s recent articles about the Sandy Hook mass shooting, and the new conspiracy thinking which has cropped up in the few days since that tragic event.

Get the Skepticality Podcast App

for Apple and Android Devices!

Get the Skepticality App — the Official Podcast App of Skeptic Magazine and the Skeptics Society, so you can enjoy your science fix and engaging interviews on the go! Available for Android, iPhone, iPad, and iPod Touch. Skepticality was the 2007 Parsec Award winner for Best “Speculative Fiction News” Podcast.

NEW ON MICHAELSHERMER.COM

The Left’s War on Science

In Michael Shermer’s February 2013 ‘Skeptic’ column for Scientific American, he discusses how politics distorts science on both ends of the spectrum.

NEW ON SKEPTICBLOG.ORG

Steven Novella Takes On Some of the Oldest Clichés

About Scientific Skepticism—Again

In this Skepticblog post, Daniel Loxton recommends a recent Steven Novella post about the scope of scientific skepticism, and shares some personal thoughts in response.

Check out these new additions

to the Skeptic.com Reading Room

THE READING ROOM is a comprehensive, free resource of articles relating to science and skepticism. The Library contains an ever-growing index of articles, reviews and opinion editorials culled from our extensive archives, offering an in depth look into the myriad of subjects the Skeptics Society has explored over the years. You can help us continue to expand on the Reading Room by donating to the Skeptics Society.

Extraterrestrials May Be Out There:

But He Says They’re Not Here

In the past half century of UFOlogy, one man stands out, among a sea of believers, as the definitive skeptic of all matters flying saucers and aliens. This interview with Philip J. Klass (1919–2005), one of the last he gave of his career, goes inside his investigations into the claims of extraterrestrial investigations. This interview was published in Skeptic magazine volume 7, number 4 in 1999.

James Randi on Quackery and

the Need for Science Education

James Randi addresses congressional representatives at the Rayburn Building, Washington, D.C., March 18th, 1999. This address appeared in Skeptic magazine volume 7, number 1 that year, in his regular column ’Twas Brillig….

About this week’s eSkeptic

In this week’s eSkeptic, Daniel Loxton shares a story about Joseph F. Rinn—a leading media skeptic from the early 20th century— whose classic volume Sixty Years of Psychical Research, though rarely consulted today, remains the deepest and most important sources of skeptical literature on paranormal investigation from about 1890–1950.

The Remarkable Mr. Rinn

by Daniel Loxton

In recent months, I’ve been digging into the forgotten history of early skeptical thinkers, authors, and activists. I’ve acquired and explored dozens of books from the nineteenth century and the first three quarters of the twentieth (the period prior to the 1976 formation of the CSICOP, which is usually considered the birth of the fully modern skeptical movement). From this research I’m developing a series of articles that include a recent Skepticblog post on the roots of the slogan “extraordinary claims demand extraordinary evidence,” my upcoming Junior Skeptic article on two hard core skeptical investigators who happened to be women, and a chapter-length project on the scope of scientific skepticism (and why it matters).

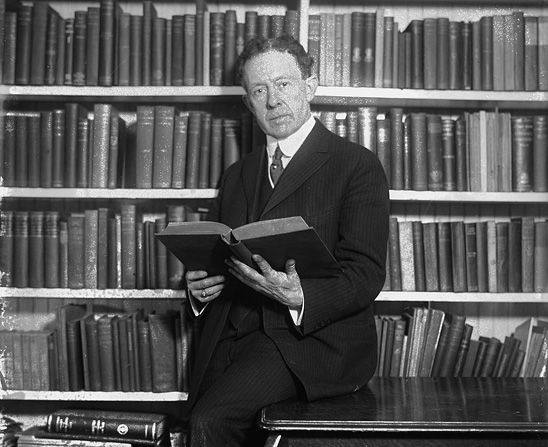

Today, I’d like to share a little about Joseph F. Rinn, a leading media skeptic who was most active in New York City in the first two decades of the twentieth century. Though his classic volume Sixty Years of Psychical Research is rarely consulted today (and a little pricey), it remains the deepest and most important source on the skeptical scene during the 1890–1950 period.

A quintessentially American success story, Rinn went into the grocery business in 1883 at just 15 years of age. “I was successful from the first,” he recalled. “In a few weeks I was making three hundred dollars per week, and the business grew steadily until by the time I was twenty I was the largest wholesale fruit and produce broker in the United States and Canada and remained so for thirty years.”1 This gave him sizable resources to devote to his real passion: paranormal claims. “As soon as my finances permitted,” he wrote, “I began buying books on philosophy, science, and psychic phenomena.” Rinn was initially very hopeful that science would validate the extravagant talking-to-the-dead claims of spirit mediums, and he was “determined to investigate.” That investigation project defined the arc of his life.

Rinn and Houdini

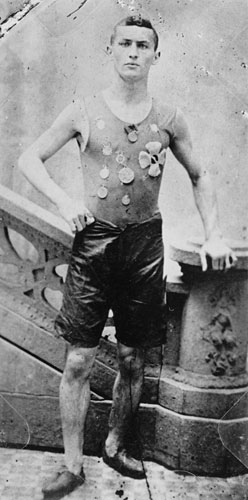

Not yet Houdini, Ehrich Weiss poses wearing medals he won as a member of the Pastime Athletic Club track team in New York (c. 1890). McManus-Young Collection (Library of Congress)

In 1886, the already rich, teenaged Rinn joined New York City’s Pastime Athletic Club. “I became the captain of the club and I was its champion sprint runner in 1889,” Rinn wrote, “when a new member joined by the name of Ehrich Weiss, who later became famous as Harry Houdini, the magician and escape artist.”2 Rinn coached young Houdini (then just 15 or so) in running, and the two bonded over Houdini’s “ambition to be a boy magician” and Rinn’s friendship with the well-known professional magician Alexander Herrmann. Rinn recalled, “In the years 1889, 1890 and 1891, Harry Houdini and I were close pals, not only at the Pastime Athletic Club but outside.”3 Rinn put a little money into Houdini’s fledgling magic career (a “Christmas present…as Houdini was quite proud and touchy about money matters”4) and they went to the theatre together often. In 1891, Houdini asked his psychical research enthusiast friend to take him to another kind of show: Houdini’s first seance.5 They remained close friends and collaborators for almost forty years. When Houdini died in 1926, Rinn was among his pallbearers.6

Rinn’s many investigations and the repeated disappointments of exposed and confessed frauds eventually persuaded him that his “earnest hope, through the years, of finding a genuine psychic would never be fulfilled,” and in 1900 Houdini urged him to put his accumulated knowledge of paranormal trickery to good use. “It’s your duty to society, as you have plenty of money and nothing to fear,” said Houdini (according to Rinn’s recollection) “to show the public what easy marks scientific investigators are for tricky psychics.” Rinn was a rare expert on mediumistic scams, and an expert magician in his own right. Why not give public demonstrations, Houdini urged, and show people exactly how the effects of fraudulent mediums were accomplished?7 Rinn ruminated on this challenge for two years, until a chance meeting at a magic shop with a magician named David P. Abbott8 who was considering writing a book exposing mediumistic trickery. They exchanged notes, talked about collaboration. Rinn resolved to begin a debunking career; Abbott, to write his book Behind the Scenes with the Mediums.

The Original American Skeptics Group?

I’m fascinated that so many of the skeptics of this period knew each other, interacted, and often worked together across an informal network of like-minded researchers and activists. But skeptical organizing at the turn of the nineteenth century went beyond the mere acquaintanceship of figures like Abbott and Rinn. Frustrated with what they considered the failure of the (American) Society for Psychical Research to expose faux-psychic fraud or interfere “in any manner” with the activities of deliberate con artists, Rinn and “a few hundred members, mostly interested in exposing fakers” formed an overtly skeptical splinter group in 1905, called the Metropolitan Psychical Society.9 Headed by notable skeptics such as Winfield S. Davis, James L. Kellogg, and of course Rinn, the Metropolitan Psychical Society is the earliest contender I know for the contested title of “first North American skeptics group.”

For the next two decades (and more) Rinn was a leading voice—perhaps the leading voice—among these skeptical investigators and activists. While Houdini struggled to build his professional career, his friend Rinn led the battle against the paranormal in major media and in darkened seance rooms. Rinn offered enormously rich cash challenges from his personal fortune, performed stage demonstrations, and even wrote a skepticism-themed crime thriller that played large stages in New York and Chicago.

Nothing New Under the Sun

The more I learn of the history of attempts to bring rigorous critical focus to the study of allegedly paranormal claims, the more I am struck by the almost steady-state picture that emerges—going back centuries, even millennia. Wherever there are people, there are extraordinary claims; and where there are extraordinary claims, there are those who ask whether these are too good to be true.

For his part, Joseph Rinn made many of the same arguments current among skeptics today, grappled with many of the same issues, and stumbled in much the same places. For example, in a typical 1911 Washington Post article, Rinn went after those scientists who endorsed the allegedly supernatural feats of spirit mediums, making an observation as pressing today as it was in his time:

When a man eminent in science tells us of something in his particular sphere, into which no fraud can intrude, and which can be verified under scientific conditions, he is entitled to a respectful hearing, but if he states that on a particular night his cow jumped over the postoffice his testimony on that point is no more valid than the testimony of other persons. The mere fact that a man is noted in his particular field of research, astronomy, physics, or mathematics should not be considered as presumptive evidence of his ability to see correctly things outside his experience.10

Similarly, Rinn touched upon an argument close to my own heart—the mutually reenforcing, pragmatic strengths of civility and testability—in this wonderful comment from 1906:

Being courteous does not necessitate being a fool, and if conditions that permit fraud are necessary for the production of psychic phenomena, we had better quit investigations. Wonderful phenomena need wonderful evidence in their support to be of any value so far as truth is concerned, otherwise they are valueless.11

But for all his knowledge and wisdom on the topic of psychic trickery, Rinn was neither a scientist nor immune to hubris. Modern skeptics risk serious factual missteps if we succumb to the fundamentally pseudoscientific temptation to elevate our own “critical thinking” or “common sense” over the domain expertise of dedicated scientific experts (a danger I warned about here). Joseph Rinn stumbled in just this fashion when he denounced smallpox vaccination as a medical sham.12 He was, of course, on the wrong side of both science and history. Thanks to vaccination, the last case of smallpox in the United States (1949) occurred within Rinn’s own lifetime. By 1977, smallpox was eliminated from the planet altogether—arguably the greatest scientific achievement in human history.13 (Rinn was hardly the first nor last admirable thinker to fall into this particular trap. In 1898, natural selection co-discoverer Alfred Russel Wallace published an entire book titled Vaccination a Delusion, Its Penal Enforcement a Crime: Proved by the Official Evidence in the Reports of the Royal Commission, followed in 1904 by the National Anti-Vaccination League booklet, A Summary of the Proofs That Vaccination Does Not Prevent Smallpox but Really Increases It.)14

All of these insights, missteps, anecdotes and arguments add up to a remarkable book about a remarkable figure in skeptical history. Rinn saw the dawn of a skeptical movement. He was present at the historic 1888 confessions to the New York Herald of Margaret Fox Kane and Kate Fox Jencken, the mediums who had inspired the religion of Spiritualism.15 He carried the baton for so many early laps that he was able to see first Harry Houdini and later Inside the Medium’s Cabinet author Joseph Dunninger as his successors. (“As Houdini had passed on and I was no longer active because of my age” a pesky psychic dared to return to New York in 1929, Rinn recalled. But “in Joseph Dunninger…we had a skilled and competent man to take up the work against fakers where I had left off.”)16

The Time We Are Given

Sixty Years of Psychical Research ends abruptly, and sadly. Rinn wrote, “The deaths of so many old friends…so depressed me that I decided it was time to bring down the curtain and close my book.” The worst of these blows were the funerals of Bess Houdini in 1943, and of Houdini’s brother Theodore Hardeen in 1945. With these, Rinn concluded: “So passed from the scene the last of my pals of boyhood days.”17 I find this one of the more haunting lines of the skeptical literature.

In an era when the activists and enthusiasts of the “skeptical movement” may struggle to recall the skeptical pioneers active within our own lifetimes (some of them still working today, after decades in the trenches), it is instructive to consider that whole skeptical careers, even fledgeling movements, flourished and vanished into history before the skeptics of the 1970s were even born. Struggles and scandals and victories, books and organizations and media coverage, campaigns and exposés and alliances, utopian hopes and misanthropic cynicism—all lost, forgotten, existing only in archives. I find that sobering, and also oddly inspiring. I am motivated to do the work of rigorous skeptical scholarship—the dry, niche, soon-to-be-forgotten hard work—by my personal values as a humanist. Humanism, as I see it, asks us how we will choose to help each other during the time that we have.

What will I do with the time I am given? What contribution shall I make, however brief, and however small? I make my choice anew every day when I hang up my humanist hat at the door, roll up my skeptical sleeves, and bend once again to the task that centuries of skeptics have toiled at before me: investigating testable paranormal claims, and then telling the public what we have learned. ![]()

References

- Rinn, Joseph. Sixty Years of Psychical Research. (The Truth Seeker Company, 1950.) p. 6

- Ibid. p. 65

- Ibid. p. 81

- Ibid. p. 65

- Ibid. p. 81

- “Harry Houdini Rites Tomorrow Morning: Services at Elks Club by Jewish Theatrical Guild, N.V.A., Masons and Magicians.” The New York Times. November 3, 1926. p. 23

- Rinn. (1950.) pp. 199–200

- Ibid.; Abbott, incidentally, invented the original version of the animated ball routine performed today by Teller, another skeptical magician. Teller. “Teller Reveals His Secrets.” Smithsonian Magazine. March 2012. (Accessed November 27, 2012.)

- Rinn. (1950.) pp.222–223

- “Ghosts and Sprits Made to Order. Mr. Joseph Rinn, Friend and Critic of Professor Hyslop, Scoffs at Psychic Phenomena and Describes How He Himself Has Reproduced Mediums’ Feats by Trickery.” The Washington Post. December 10, 1911. p. M8

- “Topics of the Times.” The New York Times. January 17, 1906. p. 10

- “Call Vaccination a Medical Sham: Speakers Tell Brooklyn Philosophical Association It Doesn’t Bring Immunity from Smallpox.” The New York Times. February 6, 1911. p. 4

- “Smallpox Disease Overview.” Centers for Disease Control. (Accessed January 21, 2013)

- Shermer, Michael. In Darwin’s Shadow. p. 216 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002.)

- Rinn. (1950.) pp. 56–64

- Ibid. p. 551

- Ibid. pp. 608–609