In this week’s eSkeptic:

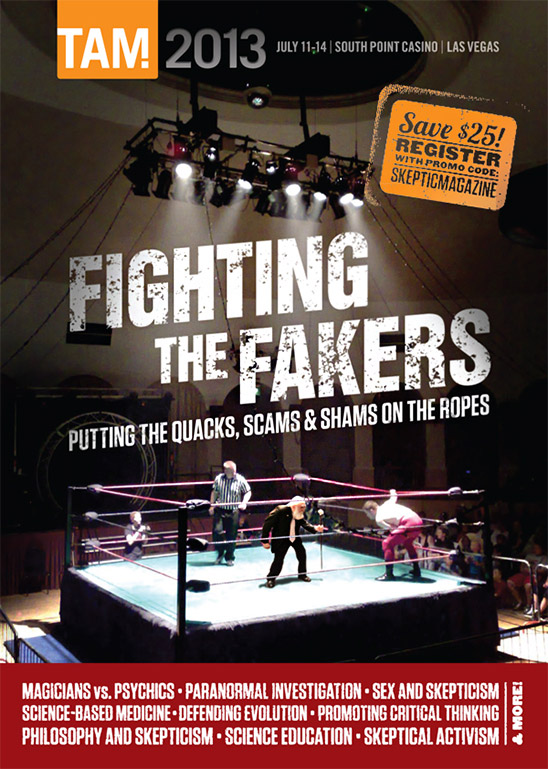

Greatest TAM Ever!

South Point Casino, Las Vegas

July 11–14, 2013

Michael Shermer on The Amazing Meeting 2013

Once again the Skeptics Society is proud to be a sponsor of the greatest skeptical gathering in the galaxy…The Amazing Meeting (TAM), featuring a stellar line up of speakers including and especially, of course, the Amazing One himself, James Randi.

The lineup of speakers this year is the best I’ve ever seen and includes Susan Jacoby, Dan Ariely, Susan Blackmore, Jerry Coyne, Susan Haack, Marty Klein, Cara Santa Maria, Steven Novella, and around 50 others as well! I am thrilled to see that climate scientist Michael Mann will also be speaking about climate denial and how to answer the critics of climate science. For my talk I’ve got all new material that I’ve been working on for my next book on how morality can be grounded in science and how humans are being more moral.

Best of all, however, in addition to all this intellectual stimulation, TAM includes countless opportunities for socializing and connecting with like-minded people—those who prefer to live in a reality-based world, those who love science and reason, and especially those who celebrate the human spirit…sometimes enhanced by good food and adult beverages available throughout the host hotel in Las Vegas over the weekend of July 11–14. —Michael Shermer, the Publisher of Skeptic magazine, Director of the Skeptics Society, and the author of The Believing Brain.

What are you waiting for?

Don’t be skeptical!

Dr. Michael Webber

What The Frak!?

SKEPTICALITY EPISODE 208

This week on Skepticality, Derek spends some time talking to Dr. Michael Webber, an alternative energy expert and advocate, based out of Austin Texas. Webber describes some of the current issues he sees related to power generation and consumption. In a time when everyone seems interested in better ways to gather and produce energy for an increasingly power-hungry world, it is good to assess all potential energy solutions—weighing their pros and cons—in the search of the silver bullet that will keep the lights on in the future.

Get the Skepticality App

Get the Skepticality App — the Official Podcast App of Skeptic Magazine and the Skeptics Society, so you can enjoy your science fix and engaging interviews on the go! Available for Android, iPhone, iPad, and iPod Touch. Skepticality was the 2007 Parsec Award winner for Best “Speculative Fiction News” Podcast.

About this week’s eSkeptic

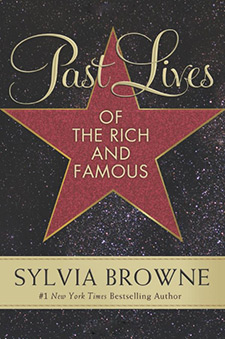

On April 21, 2003, the day before her 17th birthday, Amanda Berry was kidnapped in Cleveland, Ohio. In 2004, on an episode of the Montel Williams show, “psychic” Sylvia Browne told Amanda’s mother that Amanda was dead. Sylvia Browne’s “psychic powers” failed miserably that day. Amanda Berry is alive today, having escaped from the house where she had been held for 10 years. In this week’s eSkeptic, in light of these recent events, Ingrid Hansen Smythe reviews Sylvia Browne’s latest book Past Lives of the Rich and Famous in order to glean some insight into the mind of the “great psychic.”

Ingrid Hansen Smythe (BMus, BA, MA) is a freelance writer, playwright, and the author of three books—Dwynwen’s Feast, Stories for Animals, and Poetry for Animals. Visit her at www.ihsmythe.ca.

Sylvia Browne Takes The Case!

by Ingrid Hansen Smythe

Spiritual teacher and psychic Sylvia Browne is in the news once again in the aftermath of yet another failed prediction. Poor Sylvia! It can’t be easy having a make-believe-super-power and knowing, surely, that you’re doomed to be wrong again and again, and that only when you’re wrong will you make the headlines, at which point everyone will hate you. This is a terrible job to have, and you have to be frankly amazed at the constitution of a woman who knows that repeated public humiliation on a grand scale just goes with the territory, but who puts up with the appalling working conditions nonetheless.

Case in point: Amanda Berry, who was kidnapped and held captive by a madman—a madman who, at the time of this writing, plans to plead not guilty, even though there were chains found embedded in the walls of his basement and dog collars hanging from the ceiling. On a 2004 episode of the Montel Williams show Sylvia Browne told Amanda’s mother that her daughter was “in heaven and on the other side” and that her predictably banal and maudlin final words were “goodbye, mom, I love you.”1 (My last words would have been the name of the killer.) Browne has since apologized for her error and is ever so happy she was wrong, but other people aren’t so happy and firmly believe that telling someone their child is dead when their child isn’t dead is a despicable thing to do and, really, there ought to be a law. Was Browne’s prediction a contributing factor in Amanda Berry’s mother’s death from heart failure a year later? Who’s to know, although I just have to say right up front that if it were me and my child was missing—and Sylvia Browne told me that my child’s body would be found in a field, and then it was found in that very field—I’m afraid I’d be not-at-all inclined to believe that Sylvia Browne was psychic, and far more inclined to believe that Sylvia Browne did it.

But am I really being fair? After all, a quick tour of YouTube videos featuring Browne clearly shows that, when she’s not being debunked by some sourpuss skeptic, she’s very often right. Of course the skeptic will say that the results are being cherry-picked to include only the hits and not the misses—but the believer can turn the tables and accuse the skeptic of the very same thing, counting only the misses and not the hits. It’s a confirmation-bias problem for both sides and so I wondered, what if we temporarily ignore the issue of hits and misses and focus instead on the knowledge and wisdom Browne has to impart? I began to think that if we just gave her a chance, maybe we’d find that Sylvia Browne isn’t so bad after all. Like the above-mentioned madman who assures us he’s not guilty, maybe, I thought, poor Sylvia Browne is just misunderstood.

Thus it was in this spirit of generosity that I picked up Browne’s latest book—Past Lives of the Rich and Famous—in order to glean some insight into the mind and metaphysics of the great psychic. “Why should I not give Browne the benefit of the doubt?” I wondered. “Maybe her book is filled with tirelessly documented double-blind experiments, published in peer-reviewed scientific journals, for which the only possible explanation is reincarnation.” Anything’s not possible, obviously, but I was willing to believe her claims might be true. Willing, that is, for the first part of Browne’s book. I admit that after the first half of the first sentence things went downhill in the suspension-of-disbelief department. But I was determined and, like a lion tamer snapping his whip at the beast in his charge, I held my disbelief at bay. Besides, once the question had been raised, I found I wanted to know what, say, Steve Jobs had been doing before he was born. I imagined he might have been an apple vendor (“Get yer MacIntoshes here!”), or perhaps he wasn’t even human; perhaps he was a pea or a whale in one of their respective pods. But no. Steve Jobs was, in actual fact, Galileo, and Browne’s retelling of Galileo’s life story is as uplifting and inspiring as the picture book it paraphrases.

Just in case your own skepticism has gotten in the way of spiritual enlightenment, allow me to sum up Browne’s position. I begin with a quote:

I have an explanation … and I will never understand why there’s such reluctance among so many to embrace and celebrate that explanation, because it confirms the promise God made to all of us at the moment our souls were created—very simply, that we are eternal. It doesn’t just mean that we always will be from now on. It means we always have been.2

Are you one of those reluctant people? If so, I suspect it’s because you’re just not mentally flexible enough to seriously believe two contradictory claims. You need to be the sort of person who’s agile enough to believe that you were created in a single moment, and also that you were not created in a single moment, as Browne claims in the very same sentence. If this sort of belief is beyond you, I’m afraid you’re in for a looooooong eternity. Browne’s book itself may also seem like an eternal slog, especially because the above quote is taken from page two and, believe it or not, the truth claims only get more fantastical from there.

For example, on page three we read that we’ve been living multiple, successive lives, both in our Home On The Other Side and here in the real world—but these lives of ours on Earth are no accident, my friend. No, while at Home, each of us designs “literally every aspect of our lives”3—our rapes, our hobbies, our weddings, our addictions—every aspect. We chart these labyrinthine details meticulously on parchment scrolls, and these charts are preserved in the magnificent Hall of Records, which, by the way, is “one of the first buildings we see when we return Home”.4 (Thanks, Google Street View!) Browne doesn’t go into detail about how this intricate dance between all seven billion of us could possibly be choreographed, and I’d wager there are some pretty fierce arguments back Home between, say, people who want to be cannibals and the people they want to eat (“Listen buddy, you got to eat me last time, right?”)—but like homosexuals who are encouraged to “Pray away the gay”, skeptics should be encouraged to “Pray away the nay.” It’s best to just accept that all seven billion of us have designed our staggeringly complicated lives to play out exactly as they are—which means that if you feel like killing your mother-in-law later today, you probably shouldn’t hesitate. Don’t worry! You designed yourself to be a murderer back Home, and the stupid old bitch decided to die slowly and painfully over a period of weeks barricaded behind a brick wall in your cellar. It’s all good!

There’s a lot of homespun metaphysics in Browne’s book, like the jolly old chestnut “God doesn’t give us anything we can’t handle.”5 That’s a good one and, perversely perhaps, I want to cup my hands around my mouth and shout this bit of wisdom at, say, the next hiker who finds himself alone, wedged in a 50 foot crevasse, dying from hypothermia and asphyxiation. “It’s okay!” I’ll yell, “God wouldn’t give you anything you can’t handle! Hey, buddy, you even charted it for yourself! I’ll bet you’re regretting that one now, aren’t you?! Ha! Ah well, better luck next life!” It sounds just a bit cruel to imagine kneeling on the cold kitchen tiles, putting your head next to the woman who’s about to get the shit kicked out of her by her drunken spouse, and yelling, “It’s fine! Everything happens for a reason! You chose it so you can handle it! Ouch! Oooh, that’s gotta hurt.” I think it’s glaringly obvious that there are lots of situations we can’t handle, which is why we have rescue squads, drugs, and suicide.

Other chestnuts abound, but adopting a more scientificky tone, Browne explains how it is that we carry the marks of our past lives into our current life. It’s all down to cell memory. Browne explains:

The cells that make up our physical bodies are living, thinking, feeling organisms, which react with literal precision to the information they receive from our subconscious minds, where our spirit minds live and hold every moment and every memory of every one of our past lives.6

Who was Browne’s high school biology teacher I wonder? I’m thinking Richard Dawkins might want a word. Maybe bio classes were different in Kansas City back in the 1950s—or maybe there’s a clue in Browne’s book that explains her tendency to disregard reality and slip off to Cloud Cuckooland.

I would often sit in my classes trying not to doze off and thinking, “What on earth do square roots, or the primary export of Brazil, or the number of teeth in the mouth of the average frog have to do with preparing me for my future?”7

In other words, What do math, solid information about objective reality, and actual knowledge of the natural world have to do with anything? Browne goes on to ask another truly unfortunate, leading question: “Am I psychic, or nuts, or both?”8 she wonders, and I think many of us are biting our tongues right now, desperate to hazard a guess. Browne answers her own question, saying that, “The answer, of course, [is] neither. My Spirit Guide, Francine, gave me the in-depth explanation….”9 This woman hands these gems to her critics on a silver platter, and I think it’s fair to say that Browne’s response only lends weight to the second answer (nuts)—but once again, am I really being fair?

Because, let’s face it: there are lots of questions that science just can’t answer. What’s the difference between a duck? Why are cakes? How is a raven like a writing desk?10 Browne herself wrestles science to the mat by asking some pretty pointed questions, like how do you explain a three-year-old child born and raised in Alaska (Alaska!!!) who develops a lifelong, passionate curiosity about the American Civil War? How is it that you were born with preferences? Why are you afraid of things? And perhaps most devastatingly of all, why would a six-year-old thank his mother for breakfast, saying, “You’re the best of all twelve moms I’ve ever had?”11

Browne tells us that if you pose these questions to scientists, theologians, psychologists, and other experts, “[t]hey’re likely to reply with either a blank stare, some double-talk that makes no sense at all, or that common, meaningless response, ‘It just happens.’” This is truly shocking, but one has to wonder what class of expert Browne is engaging, and if they majored in Sack of Hammers when they got their credentials from Lenny’s Half-Baked Drive-Through University And Lube. “Oh my god!” Browne is hoping we’ll say in response to her questions. “I can’t imagine any explanation other than reincarnation!” but I think I’ve got some alternative answers for Browne and I’m guessing you do too—and crazily enough, not even one of them involves postulating Life Charts written on parchment scrolls. (Scrolls? Parchment? They haven’t heard of computers in the Great Beyond? What’s Steve Jobs doing with his afterlife anyway?)

Now—rather than just being a skeptical wet blanket, I had intended to include some of Browne’s accounts of the past lives of the rich and famous. But as I read them, I noticed that all of the stories had a blandly sensational quality that made them sound like the plot summaries of a bunch of made-for-TV-movies. Anwar Sadat was chief advisor to King Tut, Katherine Hepburn was a dancer in King Solomon’s court, Steve McQueen was a Knight Templar, Dean Martin and Sammy Davis Junior were brothers in 6th century China, Marilyn Monroe was sold to a travelling band of gypsies but rescued by her uncle who became her husband in her next life (Ew!), and so on. Plus, there were confusing plot holes in many of them—Lana Turner, for example, was born Mary Somebody-Or-Other (Francine doesn’t usually supply surnames)12 in about 1860 and lived to be 83—but the most recent Lana Turner was born in 1921, thereby creating an overlap of around 22 years. No wonder poor Lana was such a mess, marrying seven men and having one child when she meant to do it the other way around!13

The chapter on Joseph Campbell, who was Plato in a past life, was particularly rich with howlers. Like a grade 6 student asked to compose a social studies essay on an aspect of Ancient Greece, Browne writes: “Plato was opposed to the Athenian democracy of the time and was tried and convicted of religious heresy and the corruption of youth.” Whoops. Francine, who communicates via “high-pitched chirping”,14 seems to have chirped “Plato!” when she meant to chirp “Socrates!”. Browne’s unschooled, folksy, down-home approach is especially entertaining when she says, “Plato, of course, was one of this world’s earliest philosophers and the source of one of my favorite quotes: ‘We are nothing here but the shadows on the wall of the cave.’”15 Oh yeah, I love that one too. Her lack of sophistication is almost cute somehow, and certainly no one could accuse Browne of writing like an academic.

I admit that my reading became increasingly slipshod as the book progressed (“progressed” is too flattering a term really) but I’m fairly certain that not one of Browne’s subjects was gay or bisexual in a past life. You’d imagine that you might find greater variety, but the book is chock full of straight white Christians. This is very odd indeed, and after a few chapters it almost felt to me as if these stories were limited in scope by the imagination of a single person—as if they were being invented by a single mind—by a woman who could have found honest work in this life as a romance novelist or an obituary writer.

But she didn’t find honest work, did she, and this has to make you wonder. If Browne’s metaphysics is sound, and if she’s right about everything, and she really did design every aspect of her life—then why did she design herself to be such a wingnut? Seriously, she could have been someone who wasn’t convicted of investment fraud and grand theft in 1992, someone without three failed marriages, someone without a (predictably) long list of failed predictions—a list that would get any carnival guesser thrown out on his ass.

And she could have designed herself to be right about Amanda Berry.

After all the failed predictions and metaphysical mumbo jumbo, how is it that people still believe in Sylvia Browne? That’s the real mystery, but I’m guessing that any grownup who actually takes Browne’s stupefyingly harebrained superpowers seriously was very probably—and very cruelly—deprived of Scooby Doo as a child (as well as the Hardy Boys, Nancy Drew, and Encyclopedia Brown.16) The original Scooby Gang made it crystal clear that the explanation to the mystery is never the supernatural. “Francine” never turns out to be a spiritual entity. She is always at the other end of the concealed speakers or a side effect of the medication. And she is always—without exception—a product of human imagination.

I’ll be sure to pick up Sylvia Browne’s next book just in case there are new developments in the labs and government facilities and particle accelerators of reincarnation scientists around the world. And I’ll continue to feel a bit sorry for a woman whose choice of career is bound to make her despised by millions. It’s a risk she takes every time she takes a case—but I suspect the fact that we’re talking about a case stuffed full of cash helps to ease the pain. You may wonder how this woman can sleep at night, but the truth is it’s a whole lot easier when a person can afford a top-of-the-line bed and has a mattress stuffed with millions. ![]()

References

- http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2013/may/07/sylvia-browne-amanda-berry-cleveland

- Sylvia Browne. Past Lives of the Rich and Famous. New York: HarperOne, 2012. Page 2.

- Ibid., p. 20

- Ibid., p. 21.

- Ibid., p. 21.

- Ibid., p. 12.

- Ibid., p. 22.

- Ibid., p. 18.

- Ibid., p. 18.

- Actually, “Why is a raven like a writing desk?” (Lewis Carroll’s famous question) does have a brilliant answer: “Because there’s a b in both and an n in neither.” (Aldous Huxley)

- Ibid., pp. 1–2.

- She’s kind of funny that way. Francine can know for certain that someone died in 1261 from, say, an undiagnosed ruptured large intestine, but the last name of the person is a total mystery. Who knows why?

- Ibid., pp. 73–75.

- Ibid., p. 30.

- Ibid., p. 146.

- No relation. Note that Sylvia Browne used to be Sylvia Brown. “She added the e following her 1992 felony conviction and divorce from Kenzil Dalzelle Brown.” Nickell, Joe. “Sylvia Browne’s Latest: Ghost-Written?” Skeptical Inquirer, Vol. 29, No. 5. September / October 2005. p. 53. See also: http://www.randi.org/site/index.php/swift-blog/2113-yet-another-sylvia-browne-fiasco.html