In this week’s eSkeptic:

SHERMER’S SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN COLUMN ON MICHAELSHERMER.COM

Gods of the Gaps

In Michael Shermer’s July 2013 ‘Skeptic’ column for Scientific American, he explores the notion that extraterrestrial intelligences visited Earth in the distant past, and reminds us that arguments of divine intervention—alien or otherwise—start with ignorance.

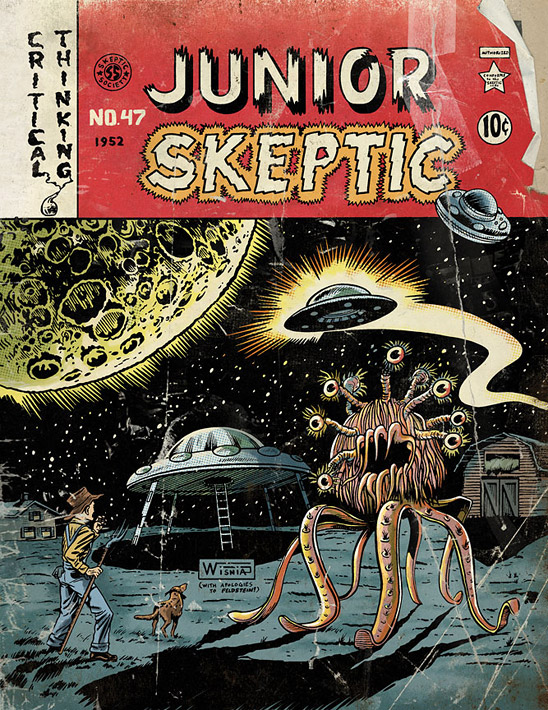

Image by Chris Wisnia and Daniel Loxton from the cover of Junior Skeptic # 47 bound within Skeptic magazine 18.2. All rights reserved.

About this week’s eSkeptic

Where did we get our ideas about being attacked from “outside”—from other lands, or from outer space? How has this idea been expressed in stories? How do exotic species here on Earth “invade” new regions? Can life forms from one planet really invade another?

In this week’s eSkeptic, we present a bit of fun from the current issue of Junior Skeptic entitled Alien Invaders! Junior Skeptic comes physically bound within every issue of Skeptic magazine. You’ll find this issue of Junior Skeptic in our current issue of Skeptic magazine (18.2), available in print and digital versions now.

Read Daniel Loxton’s bio at the end of the excerpt.

Alien Invaders!

by Daniel Loxton

All living human beings everywhere on Earth belong to the same species, Homo sapiens. Those whose ancestors lived in different parts of the Earth may look or sound different from each other, but in every important way we’re the same. People are people. We all have an incredible amount in common with one another.

Sadly, one of the many things that humans have in common is a potential for violence. We can be peaceful—trading and negotiating and working together—but we can also be fierce. Sometimes one group of people decides to fight another for things that they want, such as resources or territory. Depending on the size of the groups involved, we may call this “piracy” or “banditry,” or we may call it “war.” It’s a sad part of human nature, but it’s not unique to us. Other animals make war between groups, including chimpanzees. They’re very close relatives to humans, so it’s not surprising that chimps share some of our behaviors—cooperative and destructive. (Even animals as distantly related to us as the ants wage war against other nests or invade neighboring territories.)

Because humans can sometimes be dangerous, groups of people often distrust or fear strangers. People may feel that those who look or sound different must really be different, deep down. Sometimes people even come to believe that those that seem different must be bad people. This tendency is called “tribalism”: feeling it is important for those in your own “tribe” to be treated with respect, while outsiders can be treated badly.

Which brings us to an ancient idea that has long terrified humankind: the fear that the place we live could be invaded by cruel strangers from somewhere else. This has happened often in human history, with armies taking over other lands and displacing or oppressing the people who already lived there. Europeans invaded the New World, to the sorrow of many Native Americans. Even the mighty Roman Empire fell to “barbarian” invaders….

Space Age Paranoia

With the development of science, humankind began to realize that ours is just one planet among many. We learned that the twinkling stars in the sky are really mighty suns like ours. At the same time, we learned that our own planet was an almost unrecognizably different place at different periods in the distant past. Prehistoric times were like a series of alien worlds, right here on Earth. (“Alien” means “of an extremely different kind” or “foreign” or “belonging to another place.”)

This new knowledge changed the way we told stories about some of our most ancient fears. To express our anxieties about wars and invasions between countries, writers began to imagine invasions of really “alien” beings from outer space. For example, the 1897 Martian invasion story The War of the Worlds was a clever new twist on stories that imagined military invasions by other countries, which were a very popular type of fiction at that time.

In the 1950s and 60s, UFO legends and science fiction stories were inspired by the Space Age (the period of human exploration of space by astronauts and robotic vehicles) and the Cold War (a long period of military tension and spying between the United States and a then-powerful Communist state called the Soviet Union). Millions worried that a war using unimaginably powerful “atomic” (or later, “nuclear”) bombs could erupt at any moment and devastate the entire globe. Writers and Hollywood filmmakers made good use of these fears of Space Age atomic destruction, producing countless stories about alien invasions. In some, such as Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (1956) the aliens arrive as an unstoppable conquering military force. In others, such as Invaders from Mars (1953) and Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) the aliens invade by stealth, controlling or replacing their human victims—a reflection of American fears about Communist spies. (“They’re already here,” screams the hero of Invasion of the Body Snatchers. “You’re next!”) And in still other movies, the invaders were atomic monsters created or transformed by radiation. Radiation is a dangerous and terrifying side effect of exploding atomic bombs.

Over time, some alien invasion stories came to reflect fears of environmental destruction rather than atomic war. In the television miniseries V (1983) the aliens come to steal the Earth’s water (and also, while they’re at it, to eat all the humans). But whatever their purpose, alien invaders bring ruin—and take whatever they want in return.

Martians Invade the Earth

The grandaddy of alien invasion stories is The War of the Worlds by H. G. Wells. Published first in installments in a British magazine in 1897 and then collected as a book in 1898, War of the Worlds is a science fiction tale about an attack upon the Earth by merciless invaders from Mars. In the story, tube-shaped spacecraft 90 feet wide crash down in the English countryside. Crowds gather to marvel at these “meteorites”—only to learn the truth when the Martians lash out with their devastating “heat ray.”

Towering, tentacled, three-legged war machines emerge and march across the countryside. Britain’s army and navy are no match for these “vast spiderlike machines, nearly a hundred feet high.” People can only flee before the terrible Martian weapons—not only the “flaming death, this invisible, inevitable sword of heat” but also black clouds of poison gas that the aliens launch against the defenders of London.

Realistically told as one survivor’s personal eyewitness account, War of the Worlds is a very scary book. It may be over 100 years old, but it is as much a horror story as it is science fiction—a harsh, gruesome tale of panic and destruction and grim survival. As the San Francisco Chronicle said in an 1898 review,

Nothing in all literature is more instinct with horror and dread than the advance of these Martians across the peaceful English country… The contrast between the pastoral land and the steel-clad visitors who stalked like giants over the landscape, burning and destroying everything in their path, is so powerful that it can never be blotted from the memory.

Order Skeptic magazine issue 18.2 in print or digital format and get Junior Skeptic # 47 free inside it!

A lot of the scariness comes from the aliens’ ghastly indifference to human life and suffering. Wells described the Martians as “intellects vast and cool and unsympathetic” who viewed humans the way “a man with a microscope might scrutinise the transient creatures that swarm and multiply in a drop of water.” The Martians took no more notice of attempts to communicate or make peace than we would “of the lowing of a cow.” Their calm, methodical purpose was simply to wipe out human civilization as efficiently as possible.

Yet for all their power, the Martians had no natural defenses against Earth’s microscopic bacteria. Without any immunity, Wells wrote, the invaders “must have begun to rot almost as soon as they arrived.” In the end, the Martians’ own bodies were invaded—and destroyed—by alien germs!

Radio Panics

In 1938 a young actor named Orson Welles adapted the already-classic H. G. Wells story as a radio play for American audiences. In an extremely realistic radio broadcast, actors portraying news reporters, military commanders, government officials, and scientists told radio listeners that Martians were attacking the United States—and instructed the population of New Jersey and New York City to evacuate. Although the show was introduced as a play, many thousands of people were bewildered or frightened by the performance. Some were terrified. The New York Times reported that 875 people phoned the newspaper in concern. Thousands more called the police, or even fled to the closest police station. Thankfully, it seems no one was seriously hurt in the confusion. The next day, a visibly shaken Orson Welles told reporters,

It came, of course, as a great shock to us that the old H. G. Wells fantasy, a classic original for so many adventure stories, romances, and even comic strips should have had so profound an effect upon radio listeners. The invasion by mythical monsters from the planet Mars seemed to us to be clearly in the realm of the fairy tale. Deeply regretful that this is not so.

A 1949 Spanish-language version of Orson Welles’ radio play ended in greater sorrow. Broadcast in the capital city of Ecuador, it caused not only widespread panic, but also a savage riot. An enraged mob burned down the newspaper building where the radio station was located, killing as many as 20 people…

Read more in Junior Skeptic # 47

bound within Skeptic magazine 18.2.

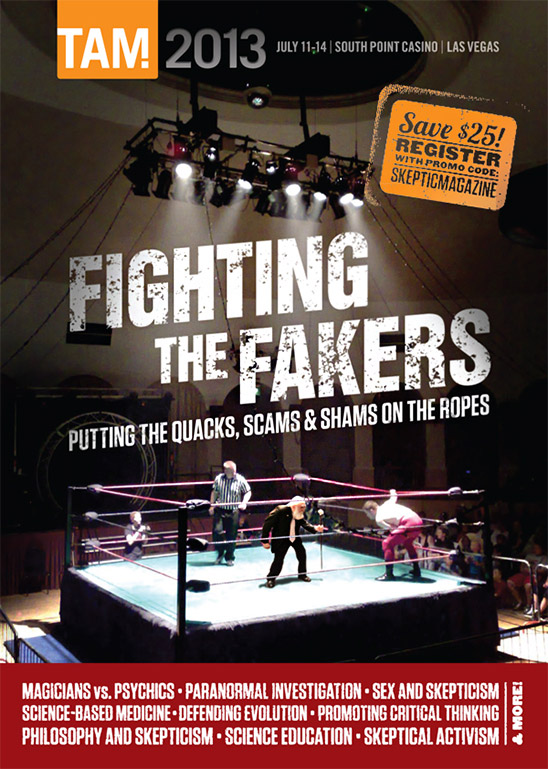

The Amazing Meeting 2013

South Point Casino, Las Vegas

July 11–14, 2013

Once again the Skeptics Society is proud to be a sponsor of the greatest skeptical gathering in the galaxy…The Amazing Meeting (TAM), featuring a stellar line up of speakers including: Susan Jacoby, Dan Ariely, Susan Blackmore, Jerry Coyne, Susan Haack, Marty Klein, Cara Santa Maria, Steven Novella, the Amazing One himself, James Randi, and around 50 others! Learn more and register online now…